Civil War in Indian Territory.

As part of the Operations to Control Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, several battles took place. After abandoning its forts in the Indian Territory early in the Civil War, the Union Army was unprepared for the logistical challenges of trying to regain control of the territory from the Confederate government.

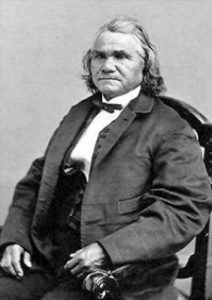

Battle of Round Mountain – November 19, 1861 – This conflict, sometimes called the Battle of Red Fork, was the first battle in the Trail of Blood on Ice campaign to control Indian Territory during the Civil War. Its primary purpose was to prevent Union supporters of the Creek Nation, led by Opothle Yahola, from fleeing Indian Territory to protect Union forces in Kansas.

After Colonel Douglas H. Cooper, the Confederate commander of the Indian Department, could not reconcile differences with Opothle Yahola, the commander of a band of Unionist Creek and Seminole, he determined to compel Opothle Yahola’s submission or drive them from the territory. Opothle Yahola’s group was estimated to number about 1,700 people and included some Union supporters from the Comanche, Delaware, Kickapoo, Wichita, and Shawnee.

Cooper set out on November 15, 1861, with about 1,400 men rode up the Deep Fork of the Canadian River to find Yahola’s camp deserted. On November 19, Cooper learned from captured prisoners that part of Yahola’s band was erecting a fort at the Red Fork of the Arkansas River. However, when Cooper’s men arrived around 4:00 p.m., they again discovered that the Indians had recently abandoned their camp.

The Confederates followed stragglers, and the 4th Texas Infantry Regiment came upon Yahola’s men on a tree line at the foot of Round Mountain. The Federal response chased the Confederate cavalry back to Cooper’s main force. Darkness prevented Cooper’s counterattack until the main enemy force was within 60 yards. After a short fight, Opothle Yahola’s men set fire to the prairie grass and retreated. The Confederates captured abandoned supplies, such as Opothle Yahola’s carriage, a dozen wagons, food, cattle, and ponies. The Confederate loss in the engagement was one captain and five men killed, three severely and one slightly wounded, and one missing. Opothle Yahola lost about 110 killed and wounded. The Confederates claimed victory because Opothle Yahola had left the area.

Battle of Chusto-Talasah – December 9, 1861 – Also known as the Battle of Bird Creek, Caving Banks, and High Shoal, this battle occurred in Tulsa County, Oklahoma. It was the second of three battles in the Trail of Blood on Ice campaign to control Indian Territory.

Following Opothle Yahola and his Union force’s defeat at Round Mountain, he retreated northeastward for safety. The force was at Chusto-Talasah (Caving Banks) on the Horseshoe Bend of Bird Creek when Colonel Douglas H. Cooper’s 1,300 Confederates attacked at about 2:00 p.m. However, Chief Opothle Yahola knew Cooper was coming and had placed his troops in a strong position in heavy timber. Cooper attacked and attempted to outflank the Federals for almost four hours, driving them across Bird Creek just before dark. Cooper camped there overnight but did not pursue the Federals because he was short of ammunition.

The Confederates claimed victory, although some sources credit Opothle Yahola’s forces with driving off the attackers. Confederate casualties were 15 killed and 37 wounded. Afterward, Chief Opothle Yahola and his band continued north to Kansas. The Chusto-Talasah battle site is on privately owned land near 86th Street North and Delaware Avenue, five miles northwest of modern-day Tulsa. A granite marker stands on the east side of Sperry, Oklahoma.

Battle of Chustenahlah – December 26, 1861 – Fought in Osage County, Oklahoma, Confederate States Army troops undertook a campaign to subdue the Native American Union sympathizers under Chief Opothle Yahola to consolidate increasing Southern control. They attacked Yahola’s band of Creek and Seminole in their camp at Chustenahlah, a well-protected cove on Bird Creek. Colonel James M. McIntosh and Colonel Douglas H. Cooper planned a combined attack, with each column moving on the camp from different directions. McIntosh left nearby Fort Gibson in the eastern Indian Territory on December 22 with 1,380 men. On December 25, McIntosh was told that Cooper’s force could not join him for a while, but he decided to attack the next day.

Colonel McIntosh attacked the camp at noon despite being outnumbered and facing severe cold weather conditions. The 1,700 pro-Union defenders were secluded in the underbrush along the slope of a rugged hill. McIntosh ordered the charge to be directly up the steep bluff on foot. As the Confederate attack progressed, the Native Americans began to fall back, taking cover for a while and moving back. The pro-Union Native Americans tried to defend their position but were forced away again by 4:00 p.m. Finally, the survivors fled but were pursued by Colonel Stand Watie, with 300 Cherokee fighting for the Confederacy.

The victorious Confederates captured 160 women and children, 20 blacks, 30 wagons, 70 yoke of oxen, about 500 Indian horses, several hundred heads of cattle, 100 sheep, and large quantities of supplies. Confederate casualties were nine killed and 40 wounded. Colonel McIntosh estimated the Union Indians’ loss was 250. The remaining Union fighters and their families trekked to Fort Row, Kansas, deprived of many provisions due to being forced to flee in haste. Nearly 2,000 died at or shortly after their arrival, primarily due to exposure and disease.

Battle of Locust Grove – July 3, 1862 – This small-scale confrontation occurred when about 250 Union troops commanded by Colonel William Weer surprised approximately 300 Confederate troops commanded by Colonel James J. Clarkson, encamped near Pipe Springs. The Confederates, unable to form a battle line, were quickly dispersed into a thicket of locust trees. The skirmish resulted in about 100 Confederate soldiers dead and about 100 wounded or captured. Their commander was one of the prisoners. The Union claimed that its losses were three killed and six wounded. The Union troops also captured most Confederate supplies, including 60 wagons, 64 mule teams, and many others. Several Confederate troops escaped capture and took off for Tahlequah and Park Hill.

Weer and his men spent the Fourth of July at the battle site, dividing the captured clothing among the victorious soldiers and apportioning all other captured supplies among the various units. After breaking camp, Weer and his men proceeded to Flat Rock, about 14 miles from Fort Gibson, which the Confederates then held. On April 8, 1864, Weer was arrested for misappropriating prisoner funds, drunkenness, and neglect of duty. He was convicted following a court martial and cashiered from the army on August 20, 1864. The battle site is East of the present-day town of Locust Grove, Oklahoma. There is a commemorative marker on Scenic Route 412 in Pipe Springs Park.

Battle of Old Fort Wayne – October 22, 1862 – Also known as the Battle of Maysville, Beattie’s Prairie, or Beaty’s Prairie, this engagement occurred in Delaware County in eastern Oklahoma when Confederate Major General Thomas C. Hindman directed troops to secure southwest Missouri and northwest Arkansas. However, Union Major General James Blunt organized his troops to stop the Confederate advance. Blunt moved towards Pea Ridge, Arkansas. Upon his arrival, the Federals learned that Colonel Douglas H. Cooper had separated from the main body and moved to Fort Wayne, in Indian Territory, while the main Confederate forces were at Huntsville, Arkansas.

Early on October 22, after a long night march, Blunt’s troops attacked the Confederate camp on Beatties Prairie near Old Fort Wayne at 7:00 a.m. The Confederates put up stiff resistance for a half-hour, but overwhelming numbers forced them to retire from the field, leaving artillery and other equipment behind. The Confederates did not stop retreating until they reached the Arkansas River’s south bank. The Federal forces captured the entire battery of cannon, supply train, and about 50 prisoners. A half-inch of snow fell the night after the battle, and the Confederates suffered tremendously without their baggage train, lost in the battle.

Blunt lost 14 men; Cooper approximately 150, including a reported 50 dead who were buried on the battlefield. For his decisive victory, Blunt was appointed major general of volunteers.

Tonkawa Massacre – October 23-24, 1862 – Pro-Union Indians attacked the Tonkawa tribe as they camped approximately four miles south of present-day Anadarko in Caddo County, Oklahoma. The Tonkawa were relocated from Texas to Indian Territory in 1859 and placed under the authority of the Wichita Agency. Rumored to be cannibals, the Tonkawa were outcasts among the southern Plains Indians. Some accounts claim that the Tonkawa had killed and eaten two Shawnee men and that they were responsible for the death and dismemberment of a young Caddo boy. This gruesome reputation and their loyalty to the Confederacy during the Civil War led to their destruction. On the night of October 23, 1862, a roving Union force of Delaware, Shawnee, Osage, and other Indians attacked the Wichita Agency. During the attack on the Confederate-held agency, the Confederate Indian agent Matthew Leeper and several other whites were killed.

Once the facility was destroyed, the marauders unleashed their fury upon the Tonkawa. Fleeing east toward Fort Arbuckle, the Tonkawa were overtaken and massacred the following morning. Roughly 150 Tonkawa died in the assault, a blow from which their population never recovered. The survivors made their way to Confederate-held Fort Belknap in Texas in 1863. The massacre completely demoralized and fractured the remnants of the tribe, who remained without a leader and lived in squalor by Fort Belknap. In 1891, 73 members of the Tonkawa were allocated 994.33 acres of federal trust land, with an additional 238.24 acres in individual allotments near the former Fort Oakland, which is today Tonkawa, Oklahoma, 12 miles west of Ponca City. The population on the reservation in 2011 was 537, with 481 officially on the tribal rolls.

Battle of Fort Gibson – May 20, 1863 – In April 1863, Union forces of the Indian Home Guard under Colonel William A. Phillips occupied Fort Gibson. Upon hearing reports of no Confederate activity in all directions, Philips sent the fort’s livestock to graze. A Union sentry failed to scout a mountain road, and Confederate forces descended on the livestock. Unwilling to move against the fort directly, the Confederates maintained a strong position five miles away along the Arkansas River. Colonel Phillips dispatched his available mounted forces against the Confederates, who succeeded in retaking most of the livestock. The Confederates made a strong attack against the Union and were able to drive them back, nearly surrounding two companies. Colonel Phillips then personally led an infantry force with an artillery battery from the fort. Reinforced by the mounted infantry already in the field, Phillips could stop the Rebel attack. The Confederates held briefly in a forest until they were routed and withdrew beyond the Arkansas River. Phillips dispatched his cavalry to give chase.

Meanwhile, word of a second Confederate force attempting a river crossing was received. Phillips returned to the fort with the infantry and artillery to counter this movement. The Rebels fired one volley and withdrew, having failed to draw away enough Union forces from the original Confederate attack on the livestock. Eight days later, Colonel Phillips’ supply train was attacked at Fort Gibson. Phillips successfully defeated the attack and saved the supply train. In July 1863, troops from Fort Gibson marched south to win the battle of Honey Springs. Fort Gibson would remain in Union control for the rest of the war.

First Battle of Cabin Creek – July 1-2, 1863 – Confederate forces with about 1,600 to 1,800 men, led by Colonel Stand Watie, sought to ambush a Union supply convoy traveling from Fort Scott, Kansas, to Fort Gibson. Colonel James Monroe Williams of the First Kansas Colored Infantry commanded the Union troops. Williams arrived at the Cabin Creek Crossing of the Texas Road near Big Cabin, Oklahoma, on July 1, 1863. He learned of the intentions of Watie’s force from captured Confederate soldiers. Owing to the unusually high water level in the creek, which reached above shoulder height, Williams delayed his attack on the Confederates until the following day. He corralled his wagons defensively on a nearby prairie. In the meantime, Watie was waiting for about 1,500 reinforcements under the command of Brigadier General William L. Cabell to join him before attacking the supply train. Cabell, however, was detained due to high water on the Grand River.

On July 2, Williams ordered a half-hour artillery bombardment before launching an assault with the Third Indian Home Guard. They failed to make it across the now waist-deep creek, pushed back by heavy Confederate fire, so the Ninth Kansas Cavalry was ordered to charge under the covering fire of the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry. With the cavalry having gained a bridgehead across the creek, Williams led the men of his regiment in a headlong charge across the stream and into the brush. This forced the Confederates back, and Williams pursued them for a quarter of a mile as they attempted to rally in a clearing. Williams then led his convoy to resupply Fort Gibson successfully. This battle marked the first instance of African American troops fighting alongside their white comrades. Confederate casualties amounted to 65 men killed, with the Union Army suffering between three and 23 dead and 30 wounded.

The action made possible the continuation of a Union force in the Indian territory, allowing the later victories at Honey Springs and Fort Smith, Arkansas. Soon after the battle, the Union established defensive outposts along the Texas Road, including one at the Cabin Creek crossing. A monument to the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry was erected on the battlefield on July 7, 2007. The American Battlefield Trust and its partners then acquired and preserved more than 88 acres of the battlefield

Battle of Honey Springs – July 17, 1863 – The Battle of Honey Springs, also known as the Affair at Elk Creek, took place on July 17, 1863. Honey Springs was an important site along the Texas Road, a north-south artery between North Texas and Baxter Springs, Kansas, or Joplin, Missouri. The side that controlled this place could control traffic along the road. Honey Springs directly threatened Fort Gibson, which controlled shipping on the upper Arkansas River. The Honey Springs Depot, a site of frequent skirmishes, was chosen by Union General James G. Blunt as the place to engage the most significant Confederate forces in Indian Territory. Anticipating that Confederate forces under General Douglas H. Cooper would attempt to join with those under General William Cabell, who was moving to attack Fort Gibson.

Battle of HoneySprings, Oklahoma, 1863.

To prepare for an invasion, the Confederate Army sent 6,000 soldiers to the spot with provisions supplied from Fort Smith, Arkansas, Boggy Depot, Fort Cobb, Fort Arbuckle, and Fort Washita. However, the Confederates failed to stop a 200-wagon Federal supply train in an engagement known as the Battle of Cabin Creek.

Union General James Blunt arrived in the area on July 11, finding the Arkansas River was high, and ordered his troops to build boats to ferry them across the river. During this time, he contracted encephalitis because he had to spend July 14 in bed fighting a high fever. Blunt’s troops crossed the Arkansas River in the late afternoon of July 16. Blunt’s command included three federal Indian Home Guard Regiments recruited from all the Five Nations and the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, with two white cavalry battalions — the 6th Kansas and 3rd Wisconsin, a white infantry battalion consisting of six companies of the 2nd Colorado Infantry Regiment, and two Kansas artillery batteries.

Blunt and his troops approached Honey Springs on July 17, 1863, with a force of 3,000 men, including Native Americans and African-American former slaves. That morning, he engaged Confederate General Douglas Cooper, who commanded a force of 3,000–6,000 men composed primarily of Native Americans. Cooper’s troops became unorganized and retreated when wet gunpowder caused misfires, and rain hampered their movements. Victorious Union forces took possession of the Honey Springs depot, burning what couldn’t be immediately used and occupying the field. Blunt trumpeted the battle as a major victory, claiming Union losses of only 76, including 17 dead and 60 wounded, with enemy casualties above 500. However, Cooper reported only 181 Confederate casualties, including 134 killed or wounded and 47 taken prisoner. Cooper claimed that his enemy’s forces’ losses were over 200. The loss of the supplies at Honey Springs depot proved disastrous for the Confederate forces, who were already operating on a shoestring budget and with inadequate equipment and increasingly relied on captured Union war material to keep up the fight.

The battle was the most significant confrontation between Union and Confederate forces in the Indian Territory. The engagement was unique in the fact that white soldiers were the minority in both fighting forces. Native Americans made up a significant portion of each of the opposing armies, and the Union force also contained African-American units. Following the battle, which essentially secured the Indian Territory for the Union, guerrilla warfare became the primary means of engagement between opposing forces in the territory. The battleground is about 4.5 miles northeast of present-day Checotah, Oklahoma, 15 miles south of Muskogee, and about 20 miles southwest of Fort Gibson.

Battle of Perryville – August 23, 1863 – In what is now Pittsburg County, Oklahoma, Perryville was a central supply depot for the Confederate Army. Located halfway between Boggy Depot and Scullyville on the Texas Road, it was an important town and county seat of the Choctaw Nation.

After the Battle of Honey Springs, Confederate General Douglas Cooper retreated to Perryville, Oklahoma, where his troops could be resupplied. Union General James Blunt, who had returned to Fort Gibson, learned that the Confederates had regrouped there and believed his troops could capture the depot and destroy Cooper’s forces. Blunt reassembled a force and led them to Perryville, arriving on August 23, 1863, where he found that the Confederate commanders, Douglas Cooper, and Stand Watie, had already left for Boggy Depot. Only a small rear guard, commanded by Brigadier General William Steele, remained at Perryville.

Blunt attacked under darkness, and the two sides exchanged artillery fire. The Union forces quickly scattered the Confederates, who retreated again, leaving their supplies behind. Blunt’s forces captured whatever supplies they could use, then burned the town. Instead of following the retreating Confederates southwest toward Boggy Depot, Blunt moved eastward, where he attacked Fort Smith, Arkansas, on September 1, 1863.

Perryville was partially rebuilt after the end of the Civil War, though it did not return to its former importance or population. It survived as a community until about 1872 when the Katy railroad line reached the Choctaw town of Bucklucksy and built a railroad station named McAlester. Businesses that had stayed in Perryville moved to the area of the station, marking the end of Perryville. The battle site is about three miles south of McAlester, Oklahoma, on U. S. Highway 69.

Battle of Middle Boggy – February 13, 1864 – Also known as the Battle of Middle Boggy River or simply Battle of Middle Boggy, this skirmish occurred on February 13, 1864, in Choctaw Indian Territory, in present-day Pontotoc County.

Union Colonel William A. Phillips led an expedition of about 1,500 soldiers to divide the Confederate forces in Indian Territory along a line from Fort Gibson to the Red River. The force represented three companies of the 14th Kansas Cavalry, a battalion of Kansas Infantry, and two regiments of the Indian Home Guard, supported by howitzers from the 3rd Regiment of the Indian Home Guards. The expedition had four objectives: establishing Union Control over the Indian Territory, offering amnesty to the Creek, Seminole, and Chickasaw Indians, severing Confederate treaties with the tribes, and gaining recruits. Advancing down the Dragoon Trail toward Fort Washita, Union Colonel William A. Phillips sent out an advance of approximately 350 men from the 14th Kansas Cavalry led by Major Charles Willetts and two howitzers led by Captain Solomon Kaufman to attack a Confederate outpost guarding the Trail’s crossing of Middle Boggy River.

The Confederate force, led by Captain Jonathan Nail, comprised one company of the First Choctaw and Chickasaw Cavalry, a detachment of the 20th Texas Cavalry, and part of the Seminole Battalion of Mounted Rifles. Consisting of 90 poorly armed men, they were caught off guard when Willetts attacked them. Outnumbered and outgunned, the Confederates held off the Union cavalry attack for about 30 minutes before retreating to Lieutenant Colonel John Jumper’s Seminole Battalion, who were not at the main skirmish. The Confederates retreated 45 miles southwest down the Dragoon Trail while the Union advance continued south toward Fort Washita the next day.

The Union Army claimed victory because 49 Confederates were killed, while the Union forces suffered no deaths. When the expected reinforcements did not arrive, Philips’ Expedition into Indian Territory stalled on February 15 near old Stonewall. The outpost was about 12 miles from Muddy Boggy Depot. In 1959, the Oklahoma Historical Society erected a marker at a small cemetery about one mile north of Atoka, Oklahoma.

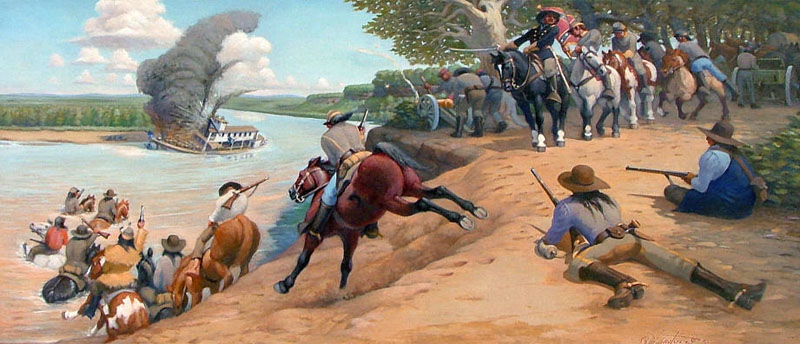

Ambush of the Steamboat J.R. Williams – June 15, 1864 – The ambush of the steamboat J.R. Williams was a military engagement on June 15, 1864, on the Arkansas River in the Choctaw Nation. It was the only naval battle in a landlocked state. It was a successful Confederate attack on the Union Army’s supply lines. The Confederate forces were Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek Indians, led by General Stand Watie, a Cherokee. At that time, the Union army was unprepared for the logistical challenges of trying to regain control of Indian Territory from the Confederate government after abandoning its forts there early in the Civil War. The area was largely undeveloped, and the Union did not have enough troops to control the few roads. Groups of Indians who sought to remain neutral in the conflict, as well as the Union-allied factions, had abandoned their farms and fled to Kansas or Missouri because of raids by Confederate-allied factions. Steamboats like J.R. Williams were used to resupply Union positions such as Fort Gibson in eastern Indian Territory via the Arkansas River instead of overland.

Steamboat J.R. Williams by Neal Taylor.

The fortunes of war had gone against the Confederate States of America by midsummer of 1863. Union victories in the southeastern states rapidly depleted the Confederate Army of men and supplies, neither of which was replaceable. The Texas units were largely withdrawn from Indian Territory, leaving only units of Native Americans, principally the Five Civilized Tribes, to defend against further Union Army incursions.

On June 15, 1864, the steamboat J.R. Williams proceeded up the Arkansas River from Fort Smith to Fort Gibson. Its cargo was primarily commissary goods and food for the Native American refugees who had recently returned from their exile in Kansas and Missouri, hoping to recover their homes and farms they had abandoned in Indian Territory. A token guard, Lieutenant Horace A B. Cook, a sergeant, and 24 privates from the 12th Regiment Kansas Volunteer Infantry—were aboard.

As the steamboat rounded a bend at Pleasant Bluff, located just below the mouth of the Canadian River near the present-day Tamaha in Haskell County, Oklahoma, a Confederate force of about 400 men, commanded by Colonel Stand Watie, opened fire with cannon and small arms. The smokestack, pilot house, and boiler were hit, disabling the vessel. The captain and crew ground the boat on the river’s north bank, opposite the Confederate position. The guardsmen opened fire, even though steam from the boiler enveloped the deck. The Confederates overwhelmed and dispersed the Union guards, disabled the vessel, looted the cargo worth $120,000, and set the steamboat afire before withdrawing. The Confederates captured six prisoners from the steamboat and killed four Union men. Afterward, many Confederate troops took their booty and disappeared, hampering General Watie’s next operation.

Second Battle of Cabin Creek – September 19, 1864 – Part of a plan conceived by Confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie, a Confederate force was to attack central Kansas from Indian Territory, raiding Union Army facilities and encouraging Indian tribes in western Kansas to join in an attack on the eastern part of the state. Watie presented the plan to his superior, General Samuel B. Maxey, on February 5, 1864. Maxey approved the plan on the condition that the attack would start by October 1, to coincide with an attack on Missouri already planned by General Sterling Price.

Brigadier-General Richard M. Gano, commanding several Texas Confederate units, and Watie met at Camp Pike in the Choctaw Nation on September 13, 1864, to plan for the coming expedition. Watie would continue to command the Indian Brigade of about 800 men, while Gano’s brigade comprised Texas cavalry and artillery units containing about 1,200 men.

The raid had targeted a wagon train that left Fort Scott on September`12 that carried supplies and provisions intended for Native Americans who had fled their homes and camped near Fort Gibson. With Major Henry Hopkins leading, the train was escorted by 80 soldiers of the 2d Kansas Cavalry, 50 men from the 6th Kansas Cavalry, and 130 men of the 14th Kansas Cavalry regiments. A group of 100 pro-Union Cherokee also joined the train at Baxter Springs, Kansas, but half were left at the Neosho River junction to guard the rear. The escort was to be increased by 170 Union Cherokee of the 2nd Indian Regiment, based at Cabin Creek, and 140 Cherokee of the 3rd Indian Regiment en route from Fort Gibson. Major Hopkins received a message to move the train to Cabin Creek as fast as possible and await further orders. The message also said that Major John A. Foreman, six companies of men, and two howitzers were en route as a relief force. The train arrived at Cabin Creek station during the afternoon of September 18.

The assault at what became the Cabin Creek battlefield began at 1:00 a.m. on September 19 as the Confederates advanced with the Texans covering the left flank and the Indian Brigade on the right flank. After the Union troops began to fire, the Confederate artillery answered. The barrage caused the mules to panic and run, many dragging their wagons. Some were so terrified that they fell off the bluff and into Cabin Creek. The teamsters cut many of the mules from their traces, jumped on them, and rode across the ford to safer ground.

At sunrise, Gano moved part of his artillery to his right flank so the wagon train would be caught in crossfire. The two Cherokee regiments moved across the creek to capture the wagons escaping in the darkness. The Texans attacked the Union flank, driving it back until the defenders were scattered in the wooded bottoms along the creek. By 9:00 a.m., the Union forces had been routed. Major Hopkins escaped to Fort Gibson, hoping to meet Major John Foreman’s relief force and recapture the train. Failing to find the relief force, he continued to Fort Gibson, bearing the news of the disaster.

The Confederate force captured a Federal wagon train with about $1 million worth of wagons, mules, commissary supplies, and other needed items. Specifically, the booty included 740 mules and 130 wagons. Although Watie and his troops were commended for their success by Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the Confederate Congress, this battle had no significant impact on the outcome of the Civil War in Indian Territory.