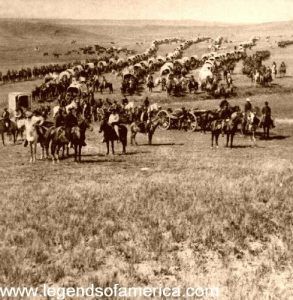

Yellowstone Expedition, 1873. Photo by William R. Pywell.

The Yellowstone Expedition of 1873 was an expedition of the United States Army in the summer of 1873 in the Dakota and Montana Territories, to survey a route for the Northern Pacific Railroad along the north side of the Yellowstone River west of the Powder River in eastern Montana.

The Northern Pacific Railroad’s proposed middle — the 250 miles between present Billings and Glendive, Montana — had yet to be surveyed, and Sioux and Cheyenne Indians opposed construction through the Yellowstone Valley, the heart of their hunting grounds. A previous surveying expedition along the Yellowstone River in 1872 had resulted in the death of a prominent member of the party, the near-death of the railroad’s chief engineer, the embarrassment of the U.S. Army, and a public relations and financial disaster for the Northern Pacific Railroad. The U.S. Army was determined to punish the Sioux, and the Northern Pacific Railroad desperately needed to complete its engineering work and resume construction.

Before the survey effort started, Chief Red Cloud, in July of 1873, stated a warning that the railroad should not be laid across his country, and was on hand to oppose the surveyor’s progress.

The expedition was under the overall command of Colonel David S. Stanley, with Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer second in command. Larger than all previous surveys combined, the survey party was escorted by 1,530 soldiers, including 27 scouts, ten companies of the 7th Cavalry under the command of George Armstrong Custer, 18 companies of infantry, 275 mule-drawn wagons, “embedded” newspaper correspondents, 353 civilians involved in the survey, 27 Indian and mixed-blood scouts supporting the column, three artillery pieces, and 60 days’ rations. They left Dakota Territory for the Yellowstone Valley to survey a route for the second transcontinental railroad, leaving a significant trail as the column passed up the valley.

This was a time when the still-powerful Lakota Sioux controlled the unceded land south of the river. As a result, the survey crews required military protection. The Cheyenne were also opposed to the railroad.

Fort Rice, North Dakota, by Seth Eastman.

The main expedition departed from Fort Rice, located in present-day North Dakota, on June 20, 1873. Four days earlier, a surveying party and six companies led by Major Edwin F. Townsend of the 9th Infantry had set out from Fort Abraham Lincoln on the Missouri River, with instructions to travel west until the central command caught up with them. During the first 17 days of marching, it rained for 14 of those days, with some instances experiencing three or four heavy rainfalls within 24 hours. After a day spent crossing the Heart River with the central command, Colonel Stanley received a report from Mr. Risser, the chief engineer, and Major Townsend. They noted that on June 24, the surveying party and its escort had been caught in a severe hailstorm, during which the men barely escaped with their lives. The storm caused the animals to stampede, resulting in significant damage to their wagons and effectively crippling both the engineers and the escort.

Stanley dispatched the remaining troops of the 7th Cavalry and a mechanic team ahead to assist the surveyors in repairing the damage. At the same time, the infantry stayed behind with the heavy wagon train. By July 1, the infantry and wagon train had crossed the flooded Muddy River, which was approximately 60 feet wide, using a makeshift pontoon bridge made from overturned wagon beds. This bridge was designed by Lieutenant P.H. Ray of the 8th Infantry, who served as the chief commissary officer. At this point, Stanley sent 47 wagons back to Fort Rice to gather additional supplies.

On July 5, the infantry escorting the wagons caught up with the surveying party led by Mr. Rosser, Major Townsend’s infantry detachment, and the 7th Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer. The expedition continued, crossing the flooded Little Missouri River and entering Montana Territory, ultimately reaching the Yellowstone River on July 13, 1873. Custer, along with two squadrons of cavalry, traveled along a rough trail to reach the mouth of Glendive Creek on the Yellowstone, where they encountered the steamboat Key West, which had established a supply depot. After Stanley arrived at the depot, he left two companies from the 7th Cavalry and one company from the 17th Infantry to guard it. On July 26, he had the Key West ferry troops and wagons across to the north bank of the Yellowstone River.

A couple of weeks into the march, Colonel Stanley began to encounter difficulties with the headstrong George Custer, a situation he had anticipated, given Custer’s reputation. Eventually, this led to an angry confrontation resulting in disciplinary action, with Custer being ordered to the rear of the command. Stanley’s authority was further undermined by his bouts of binge drinking, which Custer, a teetotaler, had a history of exploiting against his rivals. Although the conflicts between the two officers were relatively minor, some members of the command recognized that Stanley’s drunkenness contributed to the problems, prompting them to dispose of the liquor supply. About a day later, Stanley reassessed his punishment of Custer, and there were no further incidents.

After traveling west, on August 1, Stanley’s column met the Steamship Josephine under Captain Grant Marsh eight miles above the mouth of the Powder River. Captain William Ludlow of the engineers had brought the boat up with a supply of forage and some necessary clothing. That night, the expedition had the first evidence of the presence of Indians, the camp guards firing on several during the night, and the trail of ten being plainly seen going up the valley the next morning on August 2. In marching up the left bank of the Yellowstone, an escort of one company of infantry and one of the 7th Cavalry took care of the surveying party, which aimed to follow the valley. At the same time, the wagon train had to take many detours, leaving the valley and crossing the plateaus where the river ran close to the bluffs.

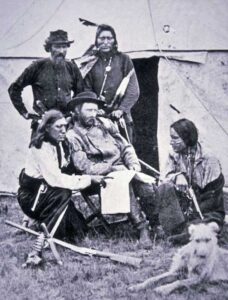

Colonel David S. Stanley.

On Sunday, August 4, 1873, Stanley’s column camped near the mouth of Sunday Creek, a tributary to the Yellowstone on the northeasterly end of Yellowstone Hill in present-day Custer County, Montana. Early that morning, the column moved up the northwest side of the hill along the south fork of Sunday Creek. Captain George W. Yates, with a company of the 7th Cavalry, accompanied the surveyors along the southeast side of the hill along the Yellowstone River. George Custer, with Companies A and B of the 7th Cavalry under the command of Captain Myles Moylan, scouted to the west ahead of Stanley’s column. Custer’s group consisted of 86 enlisted men, four officers, and Indian scouts. Custer’s brother, First Lieutenant Thomas Custer, and his brother-in-law, First Lieutenant James Calhoun, accompanied him.

After traveling west, on August 1, Stanley’s column encountered the steamship Josephine, commanded by Captain Grant Marsh, eight miles above the mouth of the Powder River. Captain William Ludlow from the engineers brought the boat up with supplies of forage and some necessary clothing. That night marked the expedition’s first evidence of the presence of Indians, as camp guards fired upon several individuals during the night, with a visible trail of ten heading up the valley observed the following morning, August 2.

While marching along the left bank of the Yellowstone River, an escort made up of one infantry company and one company from the 7th Cavalry protected a surveying party intent on following the valley. At the same time, the wagon train had to navigate numerous detours, often leaving the valley to traverse the plateaus where the river ran close to the bluffs.

On Sunday, August 4, 1873, Stanley’s column camped near the mouth of Sunday Creek, a tributary of the Yellowstone River, at the northeastern end of Yellowstone Hill, in what is now Custer County, Montana. Early that morning, the column proceeded up the northwest side of the hill along the south fork of Sunday Creek. Captain George W. Yates, along with a company from the 7th Cavalry, accompanied the surveyors along the southeastern side of the hill next to the Yellowstone River.

Meanwhile, George Custer, leading Companies A and B of the 7th Cavalry under Captain Myles Moylan, scouted west ahead of Stanley’s column. Custer’s group consisted of 86 enlisted men, four officers, and several Indian scouts. He was accompanied by his brother, First Lieutenant Thomas Custer, and his brother-in-law, First Lieutenant James Calhoun.

Shots were exchanged with Sioux Warriors near the Yellowstone River early in the battle, and George Custer’s men formed a skirmish line. A volley from the line distracted the pursuing Indians enough to halt the warriors’ charge. Custer had Captain Moylan pull back his Company A to a wooded area previously occupied by Company A. After reaching the wooded area, the cavalrymen dismounted, forming a semicircular perimeter along a former channel of the Yellowstone River. The usual configuration for dismounted cavalry was every fourth man holding horses; however, due to the length of the semicircular perimeter, only every eighth man was detailed to hold horses. The bank of the dry channel served as a natural parapet.

The warrior’s siege on the detachment of the 7th Cavalry continued for about three hours in reported 110° heat, when Custer’s mounted soldiers burst from their wooded river position in a charge that scattered the Lakota Sioux forces, who fled upriver with Custer’s men in pursuit. The soldiers pursued them for nearly four miles but were never able to close on them sufficiently to engage them.

The Yellowstone Expedition continued west on the Yellowstone River throughout August, surveying along the way. On August 11, a sharp skirmish with Chief Sitting Bull’s warriors near the mouth of the Bighorn River at what later became known as the Battle of Pease Bottom resulted in the death of Private John H. Tuttle and the critical wounding of First Lieutenant Charles Braden, both of the 7th Cavalry. An Indian bullet shattered Braden’s thigh, and the officer remained on permanent sick leave until he retired from the army in 1878.

Five days later, some of the men sought relief from the summer heat by bathing in the Yellowstone River. Suddenly, shots were fired at them by six Lakota warriors hiding near Pompey’s Pillar. One man later humorously reported that in the “ensuing scramble for cover, nude bodies scattered in all directions on the north bank for a hundred yards.” The soldiers returned fire and eventually drove the Indians away. No one was killed in the skirmish.

After scouting along the Musselshell River, Colonel David S. Stanley and the Yellowstone Expedition made their way back down the Yellowstone River. They returned to Dakota Territory in late 1873, with the expedition ending on September 23, 1873. In three months, the expedition covered nearly 1,000, often grueling miles. In three months, the expedition covered nearly 1,000, often grueling miles.

During the expedition, Colonel Staneley’s group suffered 11 men killed and one man wounded.

The Native American forces that fought against the expedition in Montana Territory were from the village of Sitting Bull, estimated at anywhere from 400 to 500 lodges with over 1000 Warriors. It included Hunkpapa Sioux under Chief Gall, accompanied by the War Chief Rain in the Face, Oglala Sioux under Crazy Horse, and Miniconjou and Cheyenne. Native American casualties while fighting the Expedition were estimated to number five killed, with numerous other warriors and horses wounded.

The campaign resulted in the encirclement of the Sioux Lands reserved by the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, putting the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe in an unfavorable position for the upcoming Great Sioux War.

Railroad construction stopped for almost a decade when the stock market crashed, leading to the Panic of 1873. A decade later, with the economy recovered and the Indian threat over, the Northern Pacific built its line south of the Yellowstone River.

Three years later, Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, Captain Thomas W. Custer, Captain George W.M. Yates, First Lieutenant James Calhoun, and Second Lieutenant Henry M. Harrington, 7th Cavalry officers accompanying the Yellowstone expedition, were all killed during the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Montana, on June 25, 1876.

Captain Myles Moylan and Second Lieutenant Charles Varnum were also present but survived the battle.

Sitting Bull, Chief Gall, Crazy Horse, and Rain in the Face, who all participated in the fighting against the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873, also participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, August 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Historic Marker Database – 1

Historic Marker Database – 2

Montana Historical Society

Stanley, David S.; Report on the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1874.

Yellowstone Genealogy Forum

Wikipedia