The Presidio of Los Adaes in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, was built on the edge of the Spanish Empire. Los Adaes was the capital of Tejas (Texas) on the northeastern frontier of New Spain from 1721 to 1773. It included a Franciscan mission, San Miguel de Cuellar de los Adaes, and a presidio, Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Los Adaes (Our Lady of the Pillar of the Adaes). Today, it’s the Los Adaes State Historic Site.

Although Spain claimed much of the Gulf Coast of North America as part of its colonial territory, it largely ignored the region to the east of the Rio Grande throughout the 17th century. In 1699, French forts were established at Biloxi Bay and on the Mississippi River, ending Spain’s exclusive control of the Gulf Coast. The Spanish recognized that French encroachment could threaten other Spanish areas, and they ordered the reoccupation of Texas as a buffer between New Spain and French settlements in Louisiana.

On April 12, 1716, an expedition led by José Domingo Ramón, a Spanish military man and explorer, left San Juan Bautista Mission in Mexico for Texas, intending to establish four missions and a presidio. At the same time, the French were building a fort in Natchitoches, having founded the town in 1714. The Spanish countered by founding two more missions just west of Natchitoches, including San Miguel de los Adaes, for a total of six missions in the region. The latter two missions were located in a disputed area; France claimed the Sabine River to be the western boundary of colonial Louisiana, while Spain claimed the Red River to be the eastern boundary of colonial Texas, leaving an overlap of 45 miles.

In 1719, European powers embarked on the War of the Quadruple Alliance. In June 1719, seven Frenchmen from Fort St. Jean Baptiste de Natchitoches took control of the mission of San Miguel de los Adaes from its sole defender, who did not know that the nations were at war. The French soldiers explained that 100 additional soldiers were coming; the Spanish colonists, missionaries, and remaining soldiers abandoned the area and fled to San Antonio.

In 1721, the Marquis de San Miguel de Aguayo volunteered to reconquer Spanish Texas and raised an army of 500 soldiers. By July 1721, Aguayo reached the Neches River. His expedition encountered a French force en route to attack San Antonio de Bexar, Texas. The outnumbered Frenchmen agreed to retreat to Louisiana. Aguayo then ordered the building of a new presidio, Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Los Adaes.

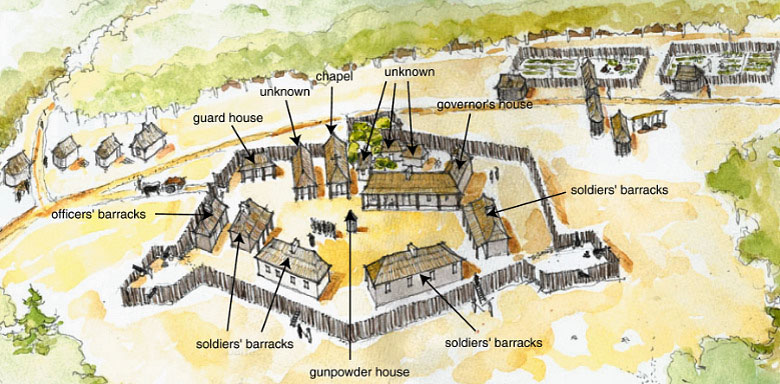

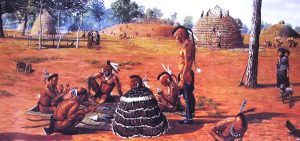

The name Adaes derives from the indigenous Adai people, members of the Caddo Confederacy, who were the people the missionaries aimed to convert to Christianity. The presidio and mission were established to counter French influence in Louisiana territory and defend New Spain (Mexico, including Texas) from possible invasion or encroachment by the French. The presidio was built in the form of a hexagon with three bastions, each of which joined two curtains 50 varas (about 46 inches) long. Six cannons that the Marqués de Aguayo had brought from Coahuila were left in the presidio, which had an initial complement of 100 soldiers. All six of the eastern Tejas missions were reopened under the protection of the new presidio. It was located near present-day Robeline, Louisiana, only 12 miles from Natchitoches. The new fort became the first capital of Texas. For the next half-century, the presidio was a vital outpost and the capital of the frontier province of Texas.

In 1729, Spain designated Los Adaes as the capital of the province of Texas. This made Los Adaes the official residence of the governor, and a house was constructed for him within the presidio. Los Adaes remained the administrative seat of government of the entire province for the next 44 years.

Northeastern New Spain in the late 18th century, courtesy Texas Beyond History.

Spain discouraged manufacturing in its colonies and limited trade to Spanish goods handled by Spanish merchants and carried on Spanish vessels. Most of the ports, including all of those in Texas, were closed to commercial vessels in the hopes of dissuading smugglers. By law, all goods bound for Texas had to be shipped to Vera Cruz and then transported over the mountains to Mexico City before being sent to Texas. This caused the goods to be costly in the Texas settlements. Because of the great distance between Los Adaes and the rest of the populated portions of Texas. As a result, the settlers in the area turned most often to the French colonists in neighboring Natchitoches, Louisiana, for trade. Without many goods to trade, however, the Spanish missionaries and colonists had little to offer the Indians, who remained loyal to the French traders.

Life at Los Adaes was harsh. Poor land and crop failures led to constant food shortages, compounded by the fact that rainy weather often meant spoiled supplies. The nearest Spanish supply post was 800 miles away, and that distance, combined with rain, floods, and hostile Native Americans, resulted in chronic shortages of everything. Without the trade of the French at Natchitoches, the inhabitants of Los Adaes would have starved. Although Spain strictly prohibited trade with the French, the latter eagerly sought it. The French took advantage of supply shortages at Los Adaes, and an illicit trade soon flourished between the two posts.

On November 3, 1762, as part of the Treaty of Fontainebleau, France ceded the portion of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River to Spain. With France no longer a threat to Spain’s North American interests, the Spanish monarchy commissioned the Marqués de Rubí to inspect all of the presidios on the northern frontier of New Spain and make recommendations for the future. Rubí was not impressed with Los Adaes, where 61 soldiers were stationed. Two Franciscan missionaries lived there, but 46 years of missionary endeavor had done “little more… than baptize a few of the dying.” Not a single Indian lived at the Mission. About 25 Spanish families lived nearby on “little ranches.” Crops were poor due to a lack of irrigation, and there was scarcely enough water to drink.

Rubi recommended that eastern Texas be abandoned, with all the population moved to San Antonio. With Louisiana in Spanish control, there was no need for a mission and presidio at Los Adaes to counter French competition.

Although the Spanish settlers in the area did not encounter hostile Native Americans, since the local Caddoan-speaking peoples were friendly, the Franciscan missionaries were unsuccessful in converting the local people to Catholicism. After many years of frustration in this regard, the College of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zacatecas, which was the sponsor of the missionaries at Los Adaes, recalled its missionaries in 1768, and the mission was closed.

In 1772, ten years after Louisiana was transferred to Spain, Los Adaes closed, and the inhabitants moved to San Antonio. By that time, the population of eastern Tejas had increased from 200 settlers of European descent to 500 people, a mixture of Spanish, French, Indians, and a few blacks. The settlers were given only five days to prepare for the move to San Antonio. Many of them perished during the three-month trek, and others died soon after arriving. At that time, Los Adaes consisted only of a hexagonal fort, defended by six cannons and 100 soldiers, and a village of about 40 “miserable houses constructed with stakes driven into the ground.” Soon thereafter, many of the soldiers and family members left San Antonio and returned to Louisiana, where their descendants live today.

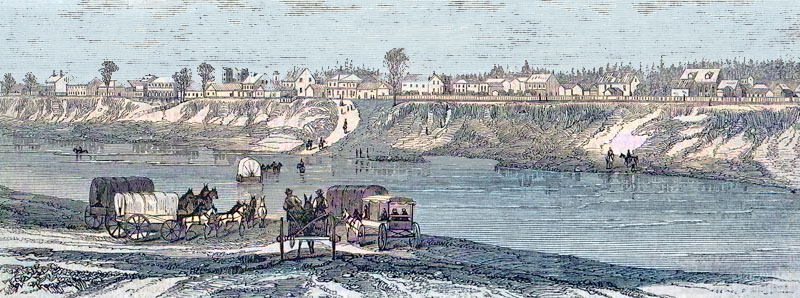

In 1779, Comanche Indians began raiding the new settlement. The former Los Adaes settlers chose to move farther east to the old mission of Natchitoches, where they founded the town of the same name. The new town quickly became a waystation for contraband.

Natchitoches, Louisiana, 1864.

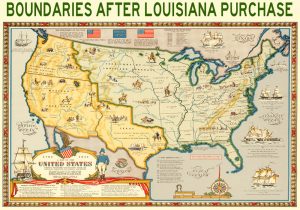

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the boundary was disputed. The Americans claimed all land to the Rio Grande, based on the French Explorer Sieur de La Salle’s claim, and the Spanish said the boundary should be between Los Adaes and Natchitoches. There were rumors in 1804 that Spain would send troops to the abandoned presidio Los Adaes.

In 1805, Captain Turner and soldiers from Fort Claiborne in Natchitoches confronted a Spanish force camped just to the northeast of Los Adaes. Turner and the Americans outnumbered the Spanish, and the Spanish withdrew. Later, in 1806, another confrontation between Spanish and American troops occurred on the Sabine River. The two commanders decided to agree to disagree rather than fight. They declared that the land between the Sabine River and the Arroyo Hondo (between Los Adaes and Natchitoches) would belong to no one—it would be a neutral strip—a no-man’s-land.

Long after the presidio had been abandoned, in 1806, the site’s strategic importance was still recognized by the signing there of a preliminary treaty between Ensign Joseph María Gonzales and Captain Edward Turner of the U.S. Army. Gonzales agreed to retreat to Spanish-owned Texas and to cease sending Spanish patrols across the border into the United States. This treaty led to the formal establishment, a few weeks later, of “neutral ground” between Texas and the United States by General James Wilkinson and Spanish Lieutenant Commander Simon de Herrera. The two nations honored the boundary for 14 years.

In 1819, the Adams-Onis Treaty, which included the United States’ purchase of Florida from Spain, also designated the Sabine River as the boundary between the U.S. and Spain. That’s how the former capital of Spanish Texas ended up in Louisiana.

Serving as the capital of the Province of Texas for 52 years, it was a place of rare cooperation among the Spanish, the French, and the Caddo Indians. On this site, visitors can explore the history, daily life, and stories that Los Adaes still reveals today.

Only a few unidentified mounds of earth are visible today on the attractive ridge where the presidio stood. Of the 40 acres or so encompassing the presidio, mission, and village sites, about nine acres are in public ownership as a historical park. The National Society of the Daughters of American Colonists and the State of Louisiana have commemorated the site with markers.

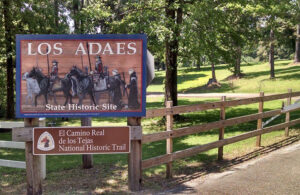

The site, now preserved in the state-run Los Adaes State Historic Site, is located on Louisiana Highway 485 in present-day Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986. It is a site on the El Camino Real de los Tejas National Historic Trail.

Today, the site of Los Adaes is near the town of Robeline, Louisiana. The Los Adaes site has proven to be one of the most important archaeological sites in the U.S. for the study of colonial Spanish and Adai culture presented by the Adai Caddo Indians of Louisiana.

Los Adaes, Louisiana, courtesy TripAdvisor.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, August 2025.

More information: Los Adaes State Historic Site

Also See:

The Army and Westward Expansion

Forts & Presidios Photo Gallery

Soldiers & Officers in American History

Sources:

Louisiana State Parks

National Park Service

National Park Service – 2

Texas State Historical Association

Wikipedia