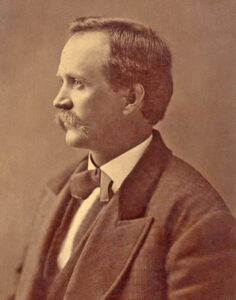

Charles Alexander Reynolds, known as “Lonesome Charley”, was a scout in the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment who was killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory. Having worked as a scout with Buffalo Bill Cody, he was noted as an expert marksman, frontiersman, and hunter.

Charles Alexander Reynolds was born in Stephensburg, Kentucky, on March 20, 1842, the fifth child of Dr. Joseph Boyer Reynolds and Phoebe Bush Reynolds. When Charley was just three years old, his mother died in June 1845 at the age of 34. Five years later, his father remarried to Lydia Burton Harding in April 1850.

At some point, his family moved to Abingdon, Illinois, where Charley attended Abingdon College for three years.

In 1859, when Charley was 17, he moved with his family to Pardee, Kansas, where his father had set up his practice.

Feeling the urge for adventure, Reynolds left his family in the spring of 1860 to work as a teamster on a wagon train headed for the Colorado gold fields. He was soon hired to be a Pony Express rider.

Reynolds was short and stocky with dark red hair and wide-set blue eyes. He was inquisitive and led a clean life.

At the beginning of the Civil War, he enlisted in Company E of the 10th Kansas Infantry, serving in Missouri and Kansas on escort duty on the Santa Fe Trail. He engaged in the Battle of Prairie Grove, Arkansas, in December 1862. He was mustered out in August 1864 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

After the war, he first engaged in an unsuccessful trading venture in New Mexico before moving to Atchison, Kansas, in 1865. Reynolds then hunted buffalo on the Republican River for a few years, and later traveled to the upper Missouri River region to trap and hunt. During this time, he became known as “Lonesome” Charley Reynolds due to his drifting from state to state and job to job, and kept his life’s details private. He preferred the company of men with whom he could share his love of geology, animal life, and Indian cultures. Otherwise, he kept to himself.

In 1867, he had a quarrel with an Army officer at Fort McPherson, Nebraska, and when it was done, the officer only had one arm left.

He began to serve in the Army out of Fort Berthold, North Dakota Territory, in 1868. By this time, he had earned a reputation as a more than capable frontiersman. The Indians who knew him called him White-Hunter-That-Never-Goes-Out-for-Nothing because of his superior hunting skills.

He met George Armstrong Custer in 1869, and Reynolds was hired to guide the first Yellowstone Expedition, which entailed escorting Northern Pacific Railroad surveyors westward in 1873. The following summer, he signed on for the second such expedition, during which he earned the respect of Custer as a quiet but superior scout. During this expedition, two civilians, Dr. Holzinger and Mr. Balarian, strayed from the column in search of fossils and were killed by the Lakota Sioux.

Later that winter, Reynolds overheard Lakota warrior Rain-in-the-Face boast of the murder at Standing Rock Agency. Reynolds reported the boast at Fort Abraham Lincoln. A detachment led by Captains George Yates and Tom Custer responded to Standing Rock, where Reynolds identified Rain-in-the-Face, who was apprehended and incarcerated.

During George Custer’s 1874 Black Hills Expedition, Reynolds carried unaccompanied the dispatches to Fort Laramie, Wyoming, that announced the discovery of gold to the public, leading to the Black Hills gold rush.

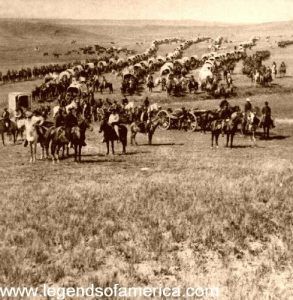

In 1876, Reynolds was hired as a scout for General Alfred Terry’s column as it set out to bring in Sitting Bull and his people. Lonesome Charley went out to determine what the troops would face, and on May 17, 1876, he guided the 7th Cavalry westward toward the Little Bighorn River. As the column moved forward in June, Reynolds developed a painful inflammation in his hand. This may have contributed to his premonition of his death in the campaign. He twice asked General Alfred Terry to be relieved but was dissuaded.

The night before the Battle of the Little Bighorn, he distributed his belongings to his friends. At the Crow’s Nest, the first sighting of the Indian village, Reynolds told Custer that this was the largest Indian village he had ever seen. This was reinforced by mixed-blood interpreter Mitch Bouyer, but gave Custer no pause. Reynolds went with the column during the battle. Major Marcus Reno’s command first dismounted in skirmish line, was flanked by Indian warriors, and then fell back to the woods along the river. In the woods, Reynolds joined Fred Girard, interpreter for the Arikara scouts. Girard later said Reynolds was extremely despondent at the time, and Girard shared his flask of liquor with him. When Major Reno called for his battalion to mount in the woods, Girard exclaimed, “What fool move is this?” Girard believed their defensive position to be a good one. Though he received the call late, Reynolds mounted his horse and, against the advice of Girard, attempted to catch the fleeing troops. Upon mounting, Reynolds observed Dr. Henry Porter attending to a mortally wounded soldier and advised the doctor to leave as the troops had left him. Reynolds then left the woods chasing after Reno’s troops. He didn’t get far before his horse was shot from under him, and he was forced to make his stand behind his horse before he was shot and killed.

Because of Charlie’s actions, Doctor Porter survived; in fact, he was the only 7th Cavalry surgeon who made it.

Doctor H.R. Porter later said, “[Lonesome Charley] fell at my side. I was tending a dying soldier in a clump of bushes just before the retreat to the bluffs when it happened. The bullets were flying, and Reynolds noticed that the Indians were making a special target of me, though I didn’t know it. He yelled at me, ‘Look out, Doctor, the Indians are shooting at you,’ and I turned to look and just in time to escape. Then I saw Reynolds throw up his hands and fall.”

Charley Reynolds was 34 years old at the time of his death at the Little Bighorn. Initially interred on the battlefield, he was disinterred in August 1877 and is believed to have been reburied in Norris, a suburb of Detroit, Michigan.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, August 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Find-a-Grave

National Park Service

Prairie Public NewsRoom

Wikipedia