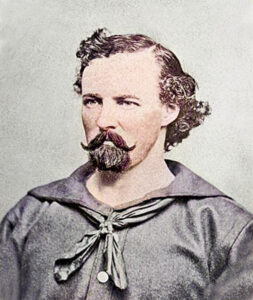

Simpson Everett “Jack” Stilwell was a United States Army Scout, U.S. Deputy Marshal, police judge, and U.S. Commissioner in Oklahoma. He served in Major George A. Forsyth’s company of scouts when it was besieged during the Battle of Beecher Island by Cheyenne War Chief Roman Nose, and was instrumental in bringing relief to his unit.

Simpson Stilwell was born to William Henry Stilwell and Charlotte B. “Sarah” Winfrey Stilwell in Iowa City, Iowa, on August 18, 1850.

In 1862, Stilwell’s father purchased land north of Baldwin City, Kansas, in Douglas County.

In 1863, William and Charlotte divorced, and William left with the three boys, Jack, Millard, and Frank, while Charlotte took the girls, Elizabeth and Mary.

That year, at the age of 14, Stilwell was sent to get some water. He never returned and made his way to Kansas City, Missouri, where he joined a wagon train bound for Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory. In the next few years, he traveled between New Mexico, Kansas City, and Leavenworth several times, spending the winters in New Mexico. During the winters, he joined others on buffalo hunts on the Canadian River, the Wolf River, and the Beaver River. In the spring, he worked the wagon trains.

Stilwell joined Company B, 18th Missouri Infantry, for a time during the Civil War.

In March 1867, he joined the U.S. Army at Fort Dodge, Kansas, when he was almost 17 years old. He entered service as a “laborer,” but by June, he was listed as a scout under Major Henry Douglass’s command.

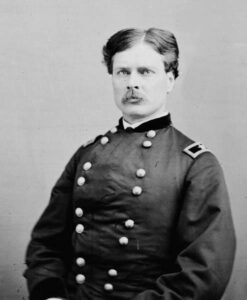

Frontier scouts, like interpreters, guides, and packers, had long been a staple in the military. They were non-soldier employees whom the Army usually hired on a month-by-month basis. When General Philip Sheridan authorized Major George A. “Sandy” Forsyth to try a new scouting tactic, raising a company of 50 “first-class handy frontiersmen to be used as Scouts against the hostile Indians,” 18-year-old Jack readily signed up on August 24, 1868. Jack had signed on with Forsyth’s Scouts at a pay rate of $75 per month, based on his furnishing his horse and tack. At that time, Stilwell was described as “a youth of six feet three or more, short of years but long on frontier lore.”

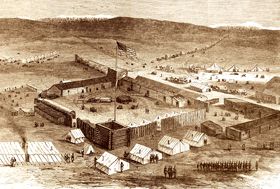

These scouts were first known as the “Solomon Avengers” and soon as “Forsyth’s Scouts,” in honor of their commander. Of the 50 total scouts, 30 were enrolled at Fort Harker and 20 more at Fort Hays, Kansas. Within five days of their enrollment, the column left Fort Hays for a scout in the area of the Solomon River, where Indian depredations had resulted in the deaths of several settlers. Finding no Indians, the scouts rode farther west to Fort Wallace, Kansas, arriving there on September 5.

On the morning of September 10, Major Forsyth’s troops at Fort Wallace received information that Cheyenne Indians had attacked a freight train about eight miles east of Fort Wallace. The soldiers and scouts set out at dawn to find the hostile Indians.

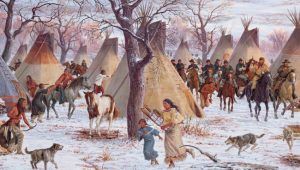

Trailing the Indian raiding party into Colorado, signs indicated that the Indian force considerably outnumbered the scouts, but the unit pressed on. The detachment went into camp on the Arikaree Fork of the Republican River, where Major Forsyth anticipated trouble and posted a watch. At dawn, on September 17, the Scouts were attacked by an overwhelming number of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers under Chief Roman Nose.

The frontiersman fought their way to a little sandbar on the Arikaree River, near present-day Wray, Colorado, and hunkered down to make a stand. Known as the Battle of Beecher Island, they dug into the dirt and firing from behind their dead horses, Jack and the others repelled charge after charge from the warriors, sustaining their fair share of casualties in the process. When the smoke finally cleared that night, four scouts were dead, along with 15 wounded, including Major Forsyth. Around midnight, Forsyth said, “Someone must go to Wallace for assistance.”

The Battle of Beecher’s Island, Colorado by Frederic Remington.

Early the next morning, Jack volunteered to go for help. He was initially rebuked as being too young. Still, the incapacitated Forsyth quickly scribbled off a note and bid Stilwell and another scout named Pierre Trudeau good luck, likely thinking he’d never see either of them again. As a matter of fact, the Major would soon send out an additional two men, under the assumption that Jack and Pierre wouldn’t make it.

Nevertheless, and against all odds, Stilwell and Trudeau were able to sneak their way through hundreds of warriors, crawling on their bellies the first several miles. For the next couple of days, the pair would travel only at night, eating horse meat for food, and when it spoiled, they got sick. Trudeau was so weak he could only stand with assistance, but after resting and traveling for four days, they reached Fort Wallace and delivered Forsyth’s dispatch.

Although exhausted, Jack insisted on joining Bankhead’s command to witness the rescue. His feet were bruised, sore, swollen, and stung full of cactus needles and thistles. He bound them up with strips from his blanket and then got in an “ambulance” that transported him from Fort Wallace to Beecher Island, a two-day journey. Upon arriving, he forgot his condition and rushed to meet his comrades, his eyes filled with tears of joy at seeing them alive. Scout John Hurst later described the teenage Jack during this event as “one of the bravest, nerviest and coolest men in the command.”

The scouts were discharged at Fort Wallace on October 5, 1868.

After several weeks of recovery at Fort Wallace, 17 of the Forsyth Scouts, including Jack, went to Fort Hays. There, on October 20, they were placed under the command of Captain Amos S. Kimball’s roll. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody recorded in his biography that Fort Hays was where he met and spent a few days with the “survivors of this terrible fight.”

On October 31, Brevet Lieutenant Colonel J. Schuyler Crosby directed Captain Kimball to “pay S.E. Stillwell, Scout and Guide now on your rolls, up to and after November 1, 1868, at the rate of $100 per month from his last payment as one of Forsyth’s Scouts—transferred.” The pay rate of $100 per month was exceptional, and Jack was one of only three scouts to receive such a fee. Bill Cody, who served under the same command, was receiving only $75 per month.

After receiving constant appeals for aid, on November 4, 1868, Samuel Johnson Crawford resigned as governor and was appointed Colonel of a newly recruited regiment, the 1,200-strong 19th Kansas Volunteers. General Philip Sheridan gave Crawford instructions to rendezvous with Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry at Fort Supply, Oklahoma, near the point of the Wolf and Beaver Rivers. Custer was under orders to proceed to the Washita River, the winter encampment of Indians.

General Phillip Sheridan had sent two guides to lead Colonel Crawford through. Jack Stilwell and Pierre Trudeau were assigned to the Kansas Volunteers as Scouts. Wichita, Kansas, resident James R. Mead wrote afterward that he talked to Stilwell and Tredeau and learned they had never been over the routes. He then went to Colonel Crawford and told him it was very dangerous to start across there at that time of year with inexperienced guides and offered to furnish a man who knew the country. Colonel Crawford replied, “I have no funds to employ scouts, so I must trust the scouts that Sheridan sends.” Sure enough, just as Mead predicted, they got lost. A big snowstorm overtook them, and forage and rations were exhausted. The men suffered much, and many of the horses froze to death on the picket line.

The Regiment began their trip Southward to Fort Supply, where Custer and the 7th Cavalry were posted. After crossing the nearly frozen Arkansas River, they began tracking the hostiles. The snow, being around 12 inches deep, made it very difficult for the men and their horses to travel, so their progress was slow. On November 14, the regiment was hit by a severe winter snowstorm, and they had great difficulty finding a way to cross the Arkansas River. Shortly afterward, 600 of their horses were somehow stampeded, resulting in the loss of 100 horses. The situation worsened when the men became lost in a blizzard in the Cimarron Canyon and finally reached Camp Supply on November 28.

Custer had grown impatient waiting for Crawford and left on November 24 for the Washita River. There, they killed from 14 to upwards of 140 Indians at the Battle of Washita, capturing 53 women and children, while losing only one officer in the fight around the Indian village. This was the battle for which the unit had been organized.

The Kansas Volunteers remained in active service all winter. They suffered from insufficient and poor rations, severe weather, and had to walk instead of ride due to the lack of horses, and saw little fighting.

In 1871, Stilwell was transferred to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, as a post guide. In the summer of 1872, he made a trip from Fort Sill to Fort Dodge, Kansas, with General Phillip Sheridan. This was just prior to the beginning of the great slaughter of the buffalo herds. The trip would mark the beginning of the end for the massive herds of bison, as Sheridan noted. Soon after that, there were more than 90,000,000 animals in a single herd that stretched 400 miles in length and 150 miles in width. This observation on the part of Sheridan was primarily responsible for the coming onslaught of white buffalo hunters that decimated the bison herds.

In the fall of 1872, Kiowa Chiefs Satanta and Big Tree were returned from Texas, where they were serving life sentences for their leadership in the attack on Henry Warren’s wagon train in Texas in 1871. However, officials at Fort Sill were not prepared to accept custody of the Kiowa as they feared a general uprising upon their return to their people. Receiving word that Fort Sill was to be the final destination, Major George W. Schofield, commanding Fort Sill, sent Jack Stilwell to intercept and turn the escort coming from Texas. Jack set out and located the escort several miles south of the Red River. Lieutenant Robert G. Carter was in command of the detachment. After conferring with Stilwell and reading Schofield’s order, Carter opted to proceed with his prisoners to Atoka in southeastern Indian Territory.

Stilwell also served during the campaign of 1874, where he made a daring ride from the Darlington Agency on the Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation to Fort Sill, 75 miles alone through hostile country, to bring news of the outbreak and get help. Later, he was a scout for General “Black Jack” Davidson.

In April 1875, Jack and one other man made a trip into the Staked Plains and induced the Quahada Comanche, under the leadership of Mow-way and Quanah Parker, to surrender.

In 1877, Jack and his younger brother, Frank Stilwell, made a trip from Anadarko, Oklahoma, to Prescott, Arizona. While there, Frank fell in with a bad element and killed a Mexican cook named Jesus Bega in October 1877. However, he was acquitted. In the meantime, Jack returned east.

In 1878, Jack went to Fort Davis and Fort Stockton, Texas, working as a chief packer and then a scout.

In 1882, Jack Stilwell’s brother Frank Stilwell was an outlaw Cowboy who was suspected of murdering Morgan Earp on March 18, 1882, in an ambush in Tombstone, Arizona. Two days later, Frank was killed in Tucson, Arizona, by Wyatt Earp’s Vendetta Posse.

Jack soon learned of his brother’s death and went west to avenge his murder. After several weeks of unsuccessfully hunting the Earps with Pete Spence, Johnny Ringo, and other Arizona cowboys, Jack gave up the search and returned to Oklahoma.

In 1885, he became a Deputy U.S. Marshal commissioned by the Northern District of Texas. In 1887, he was commissioned by the District of Kansas.

He was working out of Darlington, Oklahoma, during the period when Oklahoma was opened up for settlement. He soon became a police judge at El Reno, Oklahoma, about six miles away.

In March 1894, Stilwell was a witness in the case The United States vs. The State of Texas, which determined Greer County was within the borders of Oklahoma Territory. A few years later, he went to Anadarko, where he was appointed U.S. Commissioner. He was then admitted to the bar and practiced law.

On May 2, 1895, in Braddock, Pennsylvania, he married Esther Hannah White.

In 1898, Stilwell and his bride, Esther, were invited by longtime friend William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody to move to his ranch near Cody, Wyoming. Stilwell watched over Cody’s interests while he toured with his Wild West shows and received another appointment as a U.S. commissioner. He owned a small ranch on the South Fork of the Shoshone River, where he died of pneumonia on February 24, 1903. He was buried near Cody, Wyoming.

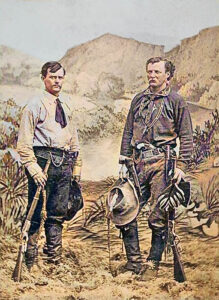

Jack Stilwell (at right) stands with James N. Jones, a fellow scout at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in about 1874.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, August 2025.

Also See:

Soldiers and Officers in American History

Sources:

Find-a-Grave

Lawmen Genealogy

True West Magazine

Wikipedia

Wild West Newsletter