The Panic of 1873 triggered the first “Great Depression”, also called the Long Depression, in the United States and abroad. The depression lasted 65 months and was the most prolonged economic contraction in American history, including the later, more famous, 45-month-long Great Depression of the 1930s.

After the Civil War, there was a significant increase in railroad construction. Between 1866 and 1873, 35,000 miles of new tracks were laid across the country. Much of this railroad investment was fueled by government land grants and subsidies to the railroads. The railroad industry became the largest employer outside of agriculture in the United States, involving considerable amounts of money and risk. An influx of capital from speculators led to remarkable growth in the industry, as well as in the construction of docks, factories, and related facilities. Most of the capital was invested in projects that did not provide immediate or early returns.

During this time, the U.S. banking system grew rapidly and seemed to be set on solid ground. However, the country was hit by many banking crises.

The U.S. Congress passed the Coinage Act on February 12, 1873, which changed the national silver policy. Before the Act, the U.S. had backed its currency with both gold and silver and minted both types of coins. The Act moved the United States to a de facto gold standard, which meant it would no longer buy silver at a statutory price or convert silver from the public into silver coins, but it would still mint silver dollars for export in the form of trade dollars.

The Act immediately caused a decline in silver prices, negatively impacting Western mining interests. However, this effect was somewhat mitigated by the introduction of a silver trade dollar for use in Asia and the discovery of new silver deposits in Virginia City, Nevada, which attracted new investments in mining activities. Additionally, the Act reduced the domestic money supply, leading to higher interest rates that harmed farmers and others who typically had significant debt. This situation prompted a strong public outcry, raising serious questions about the longevity of the new policy. The perception of instability in U.S. monetary policy led investors to avoid long-term obligations, especially long-term bonds. The issue was further complicated by the fact that the railroad boom was entering its later stages.

The financial panic began in Europe with the stock market crash. Investors began to sell off the investments they had in American projects, particularly railroads. In those days, railroads were a new invention, and companies had been borrowing money to get the cash they needed to build new lines. Railroad companies borrowed using bonds, which were debt securities specifying how much a company was borrowing and how much interest it would pay.

When Europeans started selling their railroad bonds, there were soon more bonds for sale than anyone wanted. Railroad companies could no longer find anyone who would lend them cash, and many went bankrupt.

One of the worst financial crises in history occurred when Jay Cooke and Company, one of the largest banks in New York City, declared bankruptcy on September 18, 1873. The bank had heavily invested in railroad construction and had previously served as the government’s chief financier for the Union military effort during the Civil War. Following this, the firm became a federal agent responsible for financing railroad construction, which involved significant amounts of money and risk.

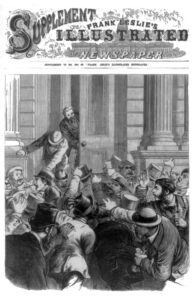

Building tracks in areas where land had not yet been cleared or settled required land grants and loans that only the government could provide. The failure of Jay Cooke’s bank, followed shortly after by the collapse of Henry Clews’ firm, triggered a chain reaction of bank failures. The collapse of the railway financiers sparked high bank withdrawals, the failure of brokerage firms, and halted railway construction. This situation temporarily closed the New York Stock Exchange for the first time on September 20, leading to a ten-day suspension of trading.

When people saw that such big banks had failed, they began to run to their banks, demanding their money back. The panic spread to banks in Washington, D.C., Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, and Georgia, as well as to banks in the Midwest, including those in Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio. Nationwide, at least 100 banks failed.

Factories began to lay off workers as the country slipped into depression. The effects of the panic were quickly felt in New York, where 25% of workers became unemployed, and more slowly in Chicago, Illinois, and Virginia City, Nevada, where silver mining was active. In New Hampshire, state coffers were so depleted by lost tax revenue that the state government turned to private interests, including tea and gunpowder manufacturer D. Ralph Lolbert, for financial support.

Many U.S. insurance companies went out of business, as the deteriorating financial conditions created solvency problems for life insurers.

Agricultural communities were also hit hard by the depression, as falling crop prices and rising debt pushed many farmers into financial ruin. The economic downturn led to an increase in foreclosures and farm bankruptcies, particularly in the Midwest and South, where reliance on credit was high.

Southern blacks suffered greatly during the depression. Preoccupied with the harsh realities of falling farm prices, wage cuts, unemployment, and labor strikes, the North became less and less concerned with addressing racism in the South. White supremacist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, which had been suppressed through punitive Reconstruction legislation starting in 1868, resumed their campaign of terror against blacks and Republicans, with violent conflicts erupting.

By November 1873, about 55 of the nation’s railroads had failed, and another 60 had gone bankrupt by the first anniversary of the crisis.

In 1874, Congress passed “the Ferry Bill” to allow for the printing of currency, increasing inflation and reducing the value of debts. President Ulysses S. Grant vetoed the bill. The following year, Congress passed the Specie Resumption Act of 1875, which would back United States currency with gold, which helped curb inflation and stabilize the dollar.

Construction of new rail lines, formerly one of the backbones of the economy, plummeted from 7,500 miles of track in 1872 to just 1,600 miles in 1875, and 18,000 businesses failed between 1873 and 1875.

Railroad Company.

By 1876, unemployment had risen to a frightening 14%.

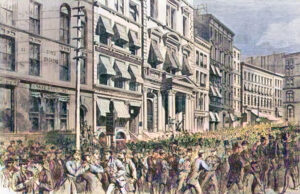

In 1877, severe wage cuts led American railroad workers to initiate a series of protests and riots known as the Great Railroad Strike. The unrest began in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad reduced workers’ pay for the third time within a year. West Virginia Governor Henry M. Mathews deployed the militia, led by Colonel Charles J. Faulkner, to restore order. Still, they were largely unsuccessful because the militia sympathized with the workers’ cause.

In response, Governor Mathews called on U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes for federal assistance, and Hayes sent federal troops to restore peace in Martinsburg. While this action did bring an end to the violence, it sparked controversy, with many newspapers criticizing Mathews for referring to the strikes as an “insurrection” instead of recognizing them as acts of desperation and frustration. The Martinsburg Statesman captured the sentiment of a striking worker who expressed that he “might as well die by the bullet as to starve to death by inches.”

The strike quickly spread to other large cities, including Baltimore, New York, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. Workers all over the country, in response to wage cuts and poor working conditions, struck and prevented trains from moving.

In July 1877, the market for lumber crashed, leading several Michigan lumber companies to go bankrupt. Within a year, the effects of this second business slump reached all the way to California.

An economic cloud settled over Ulysses S. Grant’s second term, and he tried to find a solution that would drive it away. Workers and businesspeople argued over what should be done. Grant, setting a course that would become the hallmark of the Republican Party, sided with eastern business leaders and adopted their ideas for easing the crisis. But when Grant left office in 1877, the cloud remained.

Unemployment peaked in 1878 at 8.25%. Building construction was halted, wages were cut, real estate values fell, and corporate profits vanished.

The depression ended in the spring of 1879, but tension between workers and the leaders of banking and manufacturing interests lingered on. The end of the crisis coincided with the beginning of the great wave of immigration to the United States, which lasted until the early 1920s.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Railroad Lines in American History

Sources:

Library of Congress

Public Broadcasting System

U.S. Department of the Treasury

Wikipedia