Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

On February 28, 1827, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) became the first steam-operated railway in the United States chartered for the commercial transportation of freight and passengers. Investors hoped that a railroad would allow Baltimore, Maryland, the nation’s second-largest city then, to successfully compete with New York City and its newly opened Erie Canal for Western trade. It would also compete with several existing and proposed turnpikes and canals, including the Chesapeake and Ohio Canals. In its early years, the Baltimore banker George Brown served as treasurer from 1827 until 1834 and had Ross Winans build the first real railroad car.

In the late 1820s, the fast-growing port city of Baltimore, Maryland, faced economic stagnation unless it opened a route to the Western states. Philip E. Thomas and George Brown were the pioneers of the railroad. In 1826, they investigated the best means of restoring “that portion of the Western trade which has recently been diverted from it by the introduction of steam navigation.” This included railway enterprises in England, tested comprehensively as commercial ventures.

After completing their investigation, they held an organizational meeting on February 12, 1827, including about 25 citizens, most of whom were Baltimore merchants or bankers. The pioneers’ answer was to build one of the first commercial railroad lines in the world. Their plans worked well despite many political problems from canal backers and other railroads.

The Commonwealth of Virginia, on March 8, 1827, chartered the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road Company to build a railroad from the port of Baltimore west to a suitable point on the Ohio River. The railroad, formally incorporated on April 24, was intended to provide a faster route for Midwestern goods to reach the East Coast than to the hugely successful but slow Erie Canal across upstate New York. Philip Thomas was elected the first president, and George Brown was the treasurer. The capital of the proposed company was fixed at $5,000,000, but the B&O was initially capitalized in 1827 with a $3,000,000 stock issue.

Construction began at Baltimore Harbor on July 4, 1828, with local dignitary Charles Carroll, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, laying the first stone.

The initial line of track, a 13-mile stretch to Ellicott’s Mills (now Ellicott City), Maryland, opened on May 24, 1830. A horse pulled the first car 26 miles and back. That year, inventor and businessman Peter Cooper developed and built a small coal-burning steam locomotive suitable for the B&O’s planned right of way and track. The locomotive featured an upright boiler, short wheelbase, and geared drive. On August 28, 1830, Peter Cooper’s Tom Thumb locomotive carried the B&O directors in a passenger car to Ellicott’s Mills. To the amazement of the passengers, the locomotive traveled at an impressive speed of 10-14 miles per hour. The Tom Thumb negotiated the steep, winding grades well enough to convince skeptics that steam traction worked.

The 1831 DeWitt Clinton locomotive, running between Albany and Schenectady, New York, demonstrated speeds of 25 miles per hour, dramatically decreasing the cost of transportation and announcing the coming of the end of the canal and turnpike (road) systems, many of which were never completed since they were or would soon be obsolete.

Building west from the port of Baltimore, the B&O reached Sandy Hook, Maryland, in 1834. When completed in 1837, the Cumberland Road, later the beginning of the federally financed National Road, provided a road link for animal-powered transport between Cumberland, Maryland, on the Potomac River and Wheeling, West Virginia. It was the second paved road in the country.

There was no rail link between Maryland and Virginia until the B&O opened the Harpers Ferry bridge in 1839.

In 1843, Congress appropriated $30,000 to construct an experimental 38-mile telegraph line between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore along the B&O’s right-of-way. The railroad approved the project with the agreement that it would have free use of the line upon completion. On May 24, 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse used the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad right of way to send the first telegraphic message from the Supreme Courtroom in the Capitol at Washington, D.C., to his assistant, Alfred Vail, in Baltimore.

The railroad did not reach the Ohio River at Wheeling, West Virginia, until 1852, 24 years after the project started. Yet the Ohio River was, from the beginning, the destination the railroad was seeking to link with Baltimore, at the time, a transportation center. The railroad soon became a major employer in towns such as Harpers Ferry, Martinsburg, Grafton, Parkersburg, Wheeling, and Clarksburg. The rugged terrain through what is now West Virginia slowed the construction and increased the cost. It was necessary to sell stock subscriptions and bonds in England to finance the railroad. A substantial portion of the company’s revenue came from passenger service in the first decade of its history. With the opening of the coal mines in the area around Cumberland and in the mountains west of that city, coal traffic to Baltimore became the primary source of revenue.

A technical challenge would be crossing the Appalachian Mountains, linking the new and booming territories of what at the time was the West, particularly Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky, with the East Coast rail and boat network from Maryland northward.

In 1853, after being nominated by large shareholders and director Johns Hopkins, John W. Garrett became president of the B&O, a position he would hold until he died in 1884. In the first year of his presidency, corporate operating costs were reduced from 65% of revenues to 46%, and the railroad began distributing profits to its shareholders.

The railroad grew from a capital base of $3 million in 1827 to a large enterprise generating $2.7 million annual profit on its 380 miles of track in 1854, with 19 million passenger miles. The railroad fed tens of millions of dollars of shipments to and from Baltimore and its growing hinterland to the West, thus making the city the commercial and financial capital of the region south of Philadelphia.

The B&O played a significant role and got national attention in response to abolitionist John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in October 1859. After cutting a telegraph line and stopping a B&O passenger train, he and his men occupied railroad property in his attack on the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry. After confirming that the report was not a hoax, Garrett telegraphed President James Buchanan, the Secretary of War, the Governor of Virginia, and Maryland Militia General George Hume Steuart about the insurrection in progress.

Before long, a train left Washington Depot with 87 U.S. Marines and two howitzers, while another train from nearer Frederick, Maryland, carried three Maryland militia companies. Garrett’s Master of Transportation, William Prescott Smith, left Baltimore City, together with Maryland General Charles G. Egerton Jr. and the Second Light Brigade, which train also picked up the Marines on the federal troop train at the junction in Relay, Maryland.

Brown and his men were able to overrun the arsenal. However, the following day, they were surrounded by townspeople, and soon, a company of U.S. Marines, led by Colonel Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant J. E. B. Stuart, arrived. In the meantime, Brown and his men were holed up in an Armory guard and fire engine house. On the morning of October 19, the soldiers overran Brown and his followers, and in the battle, ten of Brown’s men were killed, including two of his sons. Afterward, the engine house became known as “John Brown’s Fort.”

Garrett reported with evident relief the next day that, aside from the cut telegraph line, which was quickly repaired, no damage had been caused to any B&O track, equipment, or facilities.

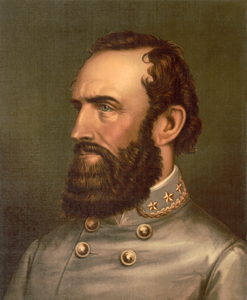

Stonewall Jackson by Strobridge Co. Lith.

Afterward, Colonel Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson commanded the cadets at Brown’s execution on December 2, 1859.

At the outset of the Civil War on April 12, 1861, the B&O possessed 236 locomotives, 128 passenger coaches, 3,451 rail cars, and 513 miles of railroad, all in states south of the Mason-Dixon line.

On April 18, 1861, the day after Virginia seceded from the Union, the Virginia militia seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, an essential workstation on the B&O’s main westward line. The following day, Confederate rioters in Baltimore attempted to prevent Pennsylvania volunteers from proceeding from the North Central Railway’s Bolton station to the B&O’s Mount Clare station. Maryland’s Governor Hicks and Baltimore Mayor George W. Brown ordered three North Central and two Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad bridges destroyed to prevent further federal troop movements and riots through the city. Soon, B&O president John Work Garrett received letters from Virginia’s Governor John Letcher telling the B&O to pass no federal troops destined for any place in Virginia over the railroad and threatening to confiscate the lines. Charles Town’s mayor also wrote, threatening to cut the B&O’s main line by destroying the long bridge over the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry, and Garrett also received anonymous threats. He and others then asked Secretary of War Simon Cameron, a major stockholder in the rival North Central Railroad, to protect the B&O as the national capitol’s main westward link. Cameron instead warned Garrett that passage of any rebel troops over his line would be treason. The Secretary of War agreed to station troops to protect the North Central, the Pennsylvania Railroad, and even the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad but flatly refused to help the B&O, his main competition.

In May 1861, Confederate Colonel Stonewall Jackson’s operations against the B&O Railroad began. Stonewall Jackson initially permitted B&O trains to operate during limited hours over approximately 100 miles from Point of Rocks to Cumberland, Maryland. By the time Jackson withdrew from Harpers Ferry in June 1861, he had systematically looted the railroad. Tools and equipment were transported deep into the Confederacy, and six locomotives were moved, part of the way over highways, to the Manassas Gap Railroad. The railroad bridge over the Potomac River was destroyed, and railroad equipment and rolling stock from Harpers Ferry to Martinsburg were damaged or destroyed.

On June 20, 1861, Jackson’s Confederates seized Martinsburg, West Virginia, a major B&O work center. Confederates confiscated dozens of locomotives and train cars and ripped up double track to ship rails for Confederate use in Virginia. Fourteen locomotives and 83 rail cars were dismantled and sent south, and another 42 locomotives, 386 rail cars, the water station, and machine shops were damaged or destroyed. In the following months, 102 miles of telegraph wire were removed. By the end of 1861, 23 B&O railroad bridges had been burned, and 36.5 miles of track were torn up or destroyed.

Since Jackson cut the B&O main line into Washington for over six months, the North Central and Pennsylvania Railroads profited from overflow traffic, even as many B&O trains stood idle in Baltimore. Garrett tried to use his government contacts to secure the needed protection. As winter began, coal prices soared in Washington, even though the B&O arranged for free coal transport from its Cumberland, Maryland, terminal down the C&O Canal in September.

The B&O had to repair the damaged line at its own expense and often received late or no payment for services rendered to the federal government.

John W. Garrett was president of the B&O during the Civil War. Though Garrett sympathized with the Southern cause, his business allegiance was to the Union. At the same time, neither a soldier nor a politician, his counsel was highly respected and trusted. He played a crucial role in helping preserve the Union during the conflict, and the railroad assumed the critical role of transporting soldiers, equipment, supplies, and wounded. Linking Washington, D.C., to the rest of the Union, soldiers were allowed to move quickly into Virginia and Confederate territory to the West. During the war, the B&O became crucial to the Federal government, the main rail connection between Washington, D.C., and the northern states, especially west of the Appalachian mountains.

He was frequently called to Washington, D.C., for advice on transportation affairs. Throughout the war, Garrett could be found either in Baltimore, where he received reports and issued orders for the movement of trains, or along the B&O rail lines, trying to maintain the morale of his men. Though the railroad continued to suffer extensive damage during the war, its dedicated employees, many living in West Virginia, reopened the line quickly and allowed the company to operate at a profit. By the time the Civil War ended, the B&O was able to expand. This began with the construction of large wrought-iron bridges over the Ohio River at Wheeling and Parkersburg.

The second half of the Civil War was characterized by near-continuous raiding, severely hampered the Union defense of Washington, D.C. Union forces and leaders often failed to secure the region properly despite the B&O’s vital importance to the Union cause.

There is no interest in suffering here except for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and I will not divide my forces to protect it.

– General Philip Sheridan

Before the Battle of Monocacy, Maryland, on July 9, 1864, B&O agents reported Confederate troop movements eleven days before the battle. Garrett had their intelligence passed to the War Department authorities and Major General Lew Wallace, who commanded the department responsible for the area’s defense. As preparations for the battle progressed, the B&O provided transport for federal troops and munitions, and on two occasions, Garrett was contacted directly by President Abraham Lincoln for further information. Though Union forces lost this battle, the delay allowed Ulysses S. Grant to repel the Confederate attack on Washington at the Battle of Fort Stevens two days later. After the battle, Lincoln paid tribute to Garrett as:

The right arm of the federal government was in the aid he rendered to the authorities to prevent the Confederates from seizing Washington and secure its retention as the capital of the Loyal States.

— Abraham Lincoln

At the end of the Civil War, the B&O had operated 520 miles of railroad. After the Civil War, the B&O consolidated several feeder lines in Virginia and West Virginia and expanded westward, bringing the line to Chicago, Illinois; St. Louis, Missouri; and Cleveland, Ohio. Six lines carried passengers and freight across the Appalachian mountain range by then.

By 1869, the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific Railroads had joined to create the first transcontinental railroad. Although pioneers continued to travel west via covered wagon, settlements grew quickly as rail transport increased the frequency and speed with which people and supplies could move across the vast continent.

By combining leases and purchases, the B&O reached Columbus, Ohio, Lake Erie, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from Cumberland, Maryland, in 1871. Other lines took the B&O into Virginia at Lexington and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The railroad industry in the 1870s underwent a significant struggle between management and labor. This peaked during the economic depression of the mid-1870s when anti-union efforts and wage cuts increased significantly. A series of national strikes began in Martinsburg in 1877 when B&O employees seized control of the railroad. Local police and the state militia could not handle the situation. When Maryland Governor John Lee Carroll attempted to put down the strike by sending the state militia from Baltimore, riots broke out, resulting in 11 deaths, the burning of parts of Camden station, and damage to several engines and cars. The next day, workers in Pittsburgh staged a sympathy strike that was also met with an assault by the state militia; Pittsburgh then erupted into widespread rioting. The strike ended after federal troops and state militias restored order, and the animosity lasted for many years.

Blockade of Engines at Martinsburg, West Virginia, in 1877, by Harper’s Weekly.

By 1884, the B&O had expanded to 1,700 miles. Unfortunately, most of this expansion had been financed by borrowed money. Furthermore, the B&O had engaged in a series of rate wars with the Pennsylvania, New York Central, and Erie Railroads, reducing operating profits. Trouble was brewing.

In 1889, the B&O hauled 31% of the nation’s Tidewater-bound soft coal; by 1896, it hauled only 4%. In the 1890s, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad commissioned William Henry Jackson to photograph scenic views along the B&O route in western Maryland.

Overexpansion and inadequate income were the major problems faced by the B&O in the late 19th century. Maintenance and service quality declined rapidly, as did traffic, much of which was lost to competitors. The railroad line went bankrupt in 1896.

The B&O recovered from receivership rapidly, partly because of the return of prosperity in the late 1890s, and it continued to expand, primarily by purchasing or entering into operating agreements with other railroads in West Virginia. After being reorganized in 1899, it added the Monongahela River Railroad in 1900, and in 1901, it reached Lake Erie. At that time, it began acquiring the Ohio River Railroad from Wheeling through Parkersburg and Huntington to Kenova.

Daniel Willard became president of the B&O in 1910, a position he would hold until 1941. Willard carried out a major system modernization, making the line one of the premier American railroads.

In the 1920s, it averaged revenues of about $225 million a year, with dividends up to 6%. At that time, operating agreements were developed with the Morgantown & Kingwood Railroad and the Coal & Coke Railway, essentially completing its routes in West Virginia. All of these railroads were eventually incorporated into the B&O.

Then came the Great Depression, hitting the B&O harder than most railroads. Barely surviving receivership, the railroad recovered briefly during World War II and into the early 1950s. Suffering from its weaker market position from Baltimore to New York, the B&O discontinued all passenger service north of Baltimore on April 26, 1958.

The decline of coal mining along its lines and increasing competition from other railroads and highways placed the company in a weak financial position by 1960. Faced with mounting debt, in 1962, the B&O accepted merger overtures from the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad while rejecting those from the New York Central. In 1963, the B&O was acquired by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway Company.

At the end of 1970, the B&O operated 5,552 miles of road and 10,449 miles of track, not including the Reading Railroad and its subsidiaries. The B&O’s long-distance passenger trains were discontinued in 1971 when the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) took over intercity passenger service. However, it continued limited commuter service in Washington, D.C., and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. About one-quarter of the B&O’s freight revenues came from its traditional haulage of bituminous coal from mines in the Allegheny Mountains. Other important freight included motor vehicles and parts as well as chemicals.

The Chessie System, a holding company headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio, was created in 1873. The company owned the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the Western Maryland Railway, and the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad.

After a series of mergers, the B&O became part of the CSX Transportation (CSX) network in 1980. Since 1987, it was merged into the Chessie System, and CSX Transportation has controlled its lines.

The railroad’s long history is featured at the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. Located at the old Mount Clare Station and adjacent roundhouse, it retains 40 acres of the B&O’s sprawling Mount Clare Shops site, which is where, in 1829, the B&O began America’s first railroad and is the oldest railroad manufacturing complex in the United States. The Railroad Museum possesses the world’s oldest and most comprehensive American railroad collections. Dating from the beginning of American railroading, the collection contains locomotives and rolling stock, historic buildings, and small objects that document the impact of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) on the growth and development of early railroading and cover almost every aspect of an industry that left a permanent mark on the folklore and culture of America. The museum and station were designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1961. The museum is located at 901 W Pratt Street in Baltimore, Maryland.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

A Century of Railroad Building

Railroad Lines in American History

Railroads & Depot Photo Gallery

Sources:

B&O Railroad Museum

Encyclopedia Britannica

Library of Congress

West Virginia Encyclopedia

Wikipedia

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Map, courtesy Wikipedia.