A Mormon missionary made a 1934 sketch of Crazy Horse after interviewing Crazy Horse’s sister, who claimed the depiction was accurate.

By Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa) in 1918

Crazy Horse was born on the Republican River in 1845. He was killed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1877, so that he lived barely 33 years.

He was an uncommonly handsome man. While not the equal of Gall in magnificence and imposing stature, he was physically perfect, an Apollo in symmetry. Furthermore, he was a true type of Indian refinement and grace. He was as modest and courteous as Chief Joseph; the difference is that he was a born warrior, while Joseph was not. However, he was a gentle warrior, a true brave, who stood for the highest ideal of the Sioux [Lakota.] Notwithstanding all that biased historians have said of him, it is only fair to judge a man by the estimate of his people rather than that of his enemies.

Crazy Horse’s boyhood was spent in the days when the western Sioux seldom saw a white man, and then it was usually a trader or a soldier. He was carefully brought up according to tribal customs.

At that period, the Sioux prided themselves on the training and development of their sons and daughters. Not a step in that development was overlooked as an excuse to bring the child before the public by giving a feast in its honor. At such times, the parents often gave so generously to the needy that they almost impoverished themselves, thus setting an example for the child of self-denial for the general good. His first step alone, the first word spoken, a first game killed, the attainment of manhood or womanhood, each was the occasion of a feast and dance in his honor, at which the poor always benefited to the full extent of the parent’s ability.

Big-heartedness, generosity, courage, and self-denial are the qualifications of a public servant, and the average Indian was keen to follow this ideal. As everyone knows, these characteristic traits become a weakness when he enters a life founded upon commerce and gain. Under such conditions, the life of Crazy Horse began. His mother, like other mothers, tender and watchful of her boy, would never once place an obstacle in the way of his father’s severe physical training. They laid the spiritual and patriotic foundations of his education in such a way that he early became conscious of the demands of public service.

He was perhaps four or five years old when the band was snowed in one severe winter. They were very short of food, but his father was a tireless hunter. The buffalo, their main dependence, were not to be found, but he was out in the storm and cold every day and finally brought in two antelopes.

The little boy got on his pet pony and rode through the camp, telling the old folks to come to his mother’s teepee for meat. It turned out that neither his father nor his mother had authorized him to do this. Before they knew it, old men and women were lined up before the teepee home, ready to receive the meat in answer to his invitation. As a result, the mother had to distribute nearly all of it, keeping only enough for two meals.

On the following day, the child asked for food. His mother told him that the old folks had taken it all and added: “Remember, my son, they went home singing praises in your name, not my name or your father’s. You must be brave. You must live up to your reputation.”

Crazy Horse loved horses, and his father gave him a pony when he was very young. He became a fine horseman and accompanied his father on buffalo hunts, holding the pack horses while the men chased the buffalo, and thus, gradually learned the art. In those days, the Sioux had but few guns, and hunting was mostly done with bows and arrows.

Another story about his boyhood is that when he was about twelve, he went to look for the ponies with his little brother, whom he loved much and took great pains to teach what he had already learned. They came to some wild cherry trees full of ripe fruit, and while they were enjoying it, the brothers were startled by the growl and sudden rush of a bear.

Young Crazy Horse pushed his brother up into the nearest tree, and himself sprang upon the back of one of the horses, which was frightened and ran some distance before he could control him. As soon as he could, however, he turned him about and came back, yelling and swinging his lariat over his head. At first, the bear showed a fight, but then it finally turned and ran. The old man who told me this story added that young as he was, he had some power so that even a grizzly did not care to tackle him. I believe it is a fact that a silver tip will dare anything except a bell or a lasso line, so accidentally, the boy hit upon the very thing that would drive him off.

It was usual for Sioux boys of his day to wait in the field after a buffalo hunt until sundown, when the young calves would come out in the open, hungrily seeking their mothers. Then, these wild children would enjoy a mimic hunt and lasso the calves or drive them into camp. Crazy Horse was found to be a determined little fellow, and it was settled one day among the larger boys that they would “stump” him to ride a good-sized bull calf. He rode the calf and stayed on its back while it ran bawling over the hills, followed by the other boys on their ponies, until his strange mount stood trembling and exhausted.

At the age of 16, he joined a war party against the Gros Ventres. He was well in the front of the charge and at once established his bravery by following closely one of the foremost Sioux warriors, by the name of Hump, drawing the enemy’s fire and circling their advance guard. Suddenly Hump’s horse was shot from under him, and there was a rush of warriors to kill or capture him while down. But amidst a shower of arrows, the youth leaped from his pony, helped his friend into his saddle, sprang up behind him, and carried him off in safety, although the enemy hotly pursued them. Thus he associated himself in his maiden battle with the wizard of Indian warfare, and Hump, who was then at the height of his own career, pronounced Crazy Horse, the coming warrior of the Teton Sioux.

At this period of his life, as was customary with the best young men, he spent much time in prayer and solitude. Just what happened in these days of his fasting in the wilderness and upon the crown of bald buttes, no one will ever know, for these things may only be known when one has lived through the battles of life to an honored old age. He was much sought after by his youthful associates but was noticeably reserved and modest, yet in the moment of danger, he at once rose above them all — a natural leader! Crazy Horse was a typical Sioux brave, and from the point of view of our race, an ideal hero, living at the height of the epical progress of the American Indian and maintaining in his character all that was most subtle and ennobling of their spiritual life, and that has since been lost in contact with a material civilization.

He loved Hump, that peerless warrior, and the two became close friends in spite of the difference in age. Men called them “the grizzly and his cub.” Again and again, the pair saved the day for the Sioux in a skirmish with some neighboring tribe. But one day, they undertook a losing battle against the Snake. The Sioux were in full retreat and were quickly overwhelmed by superior numbers. The old warrior fell in a last desperate charge, but Crazy Horse and his younger brother, though dismounted, killed two of the enemy and thus made good their retreat.

It was observed of him that when he pursued the enemy into their stronghold, as he was wont to do, he often refrained from killing and simply struck them with a switch, showing that he did not fear their weapons nor care to waste his upon them. In attempting this very feat, he lost this only brother of his, who emulated him closely. A party of young warriors, led by Crazy Horse, had dashed upon a frontier post, killed one of the sentinels, stampeded the horses, and pursued the herder to the very gate of the stockade, thus drawing upon themselves the fire of the garrison. The leader escaped without a scratch, but his young brother was brought down from his horse and killed.

While he was still under 20, there was a great winter buffalo hunt, and he came back with ten buffaloes’ tongues, which he sent to the council lodge for the councilors’ feast. He had, on one winter day, killed ten buffalo cows with his bow and arrows, and the unsuccessful hunters or those who had no swift ponies were made happy by his generosity. When the hunters returned, these came chanting songs of thanks. He knew that his father was an expert hunter and had a good horse, so he took no meat home, putting into practice the spirit of his early teaching.

He attained his majority during the crisis of difficulties between the United States and the Sioux. Even before that time, Crazy Horse had already proved his worth to his people in Indian warfare. He had risked his life again and again, and in some instances, it was considered almost a miracle that he had saved others as well as himself. He was no orator, nor was he the son of a chief. His success and influence were purely a matter of personality. He had never fought the whites up to this time, and indeed, no “coup” was counted for killing or scalping a white man.

Young Crazy Horse was 21 years old when all the Teton Sioux chiefs (the western or plains dwellers) met in council to determine their future policy toward the invader. Their former agreements had been by individual bands, each for itself, and everyone was friendly. They reasoned that the country was vast and that the white traders should be made welcome. Up to this time, they had anticipated no conflict. They had permitted the Oregon Trail, but now, to their astonishment, forts were built and garrisoned in their territory.

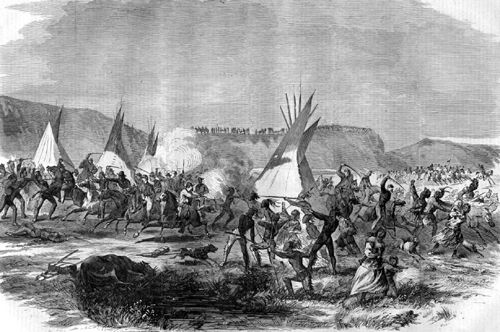

Sioux War, Harper’s Weekly, October, 1863.

Most of the chiefs advocated a strong resistance. There were a few influential men who still desired to live in peace and who were willing to make another treaty. Among these were White Bull, Two Kettle, Four Bears, and Swift Bear. Even Spotted Tail, afterward the great peace chief, was at this time with the majority, who decided in the year 1866 to defend their rights and territory by force. Attacks were to be made upon the forts within their country and on every trespasser on the same.

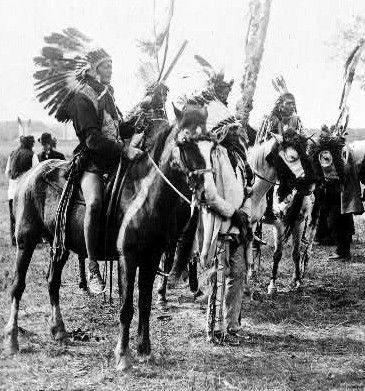

Crazy Horse took no part in the discussion, but he and all the young warriors agreed with the council’s decision. Although so young, he was already a leader among them. Other prominent young braves were Sword (brother of the man of that name who was long captain of police at Pine Ridge), the younger Hump, Charging Bear, Spotted Elk, Crow King, No Water, Big Road, He Dog, and the nephew of Red Cloud, and Touch-the-Cloud, intimate friend of Crazy Horse.

The attack on Fort Phil Kearny was the first fruit of the new policy, and here Crazy Horse was chosen to lead the attack on the woodchoppers, designed to draw the soldiers out of the fort while an army of 600 lay in wait for them. His masterful handling of his men further enhanced the success of this stratagem. From this time on, a general war was inaugurated; Sitting Bull looked to him as a principal war leader, and even the Cheyenne chiefs, allies of the Sioux, practically acknowledged his leadership.

Yet during the following ten years of defensive war, he was never known to make a speech, though his teepee was the rendezvous of the young men. He was depended upon to implement the council’s decisions and was frequently consulted by the older chiefs.

Like Osceola, he rose suddenly; like Tecumseh he was always impatient for battle; like Pontiac, he fought on while his allies were suing for peace, and like Grant, the silent soldier, he was a man of deeds and not of words. He won from Custer, Fetterman, and Crook. He won every battle that he undertook, with the exception of one or two occasions when he was surprised in the midst of his women and children, and even then, he managed to extricate himself in safety from a difficult position.

Early in 1876, his runners brought word from Sitting Bull that all the roving bands would converge upon the upper Tongue River in Montana for summer feasts and conferences. There was conflicting news from the reservation. It was rumored that the army would fight the Sioux to the finish; again, it was said that another commission would be sent out to treat them.

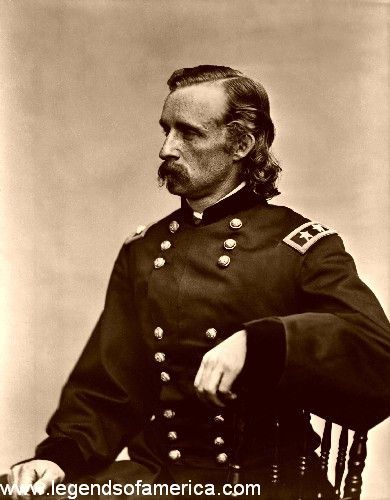

General George Crook.

The Indians came together early in June and formed a series of encampments stretching out from three to four miles, each band keeping a separate camp. On June 17, scouts came in and reported the advance of a large body of troops under General Crook. The council sent Crazy Horse, with 700 men, to meet and attack him. These were nearly all young men, many of them under 20, the flower of the hostile Sioux.

They set out at night so as to steal a march upon the enemy, but within three or four miles of his camp, they came unexpectedly upon some of his Crow scouts. There was a hurried exchange of shots; the Crows fled back to Crook’s camp, pursued by the Sioux. The soldiers had their warning, and it was impossible to enter the well-protected camp. Again and again, Crazy Horse charged with his bravest men in an attempt to bring the troops into the open, but he succeeded only in drawing their fire. Toward afternoon, he withdrew and returned to camp disappointed. His scouts remained to watch Crook’s movements and later brought word that he had retreated to Goose Creek and seemed to have no further disposition to disturb the Sioux. It is well known to us that it is Crook rather than Reno who is to be blamed for cowardice in connection with Custer’s fate. The latter had no chance to do anything; he was lucky to save himself, but if Crook had kept on his way, as ordered, to meet Terry with his one thousand regulars and 200 Crow and Shoshone scouts, he would inevitably have intercepted Custer in his advance and saved the day for him, and war with the Sioux would have ended right there. Instead of this, he fell back upon Fort Meade, eating his horses on the way in a country swarming with game for fear of Crazy Horse and his braves!

The Indians now crossed the divide between the Tongue and the Little Big Horn, where they felt safe from immediate pursuit. Here, with all their precautions, they were caught unawares by General Custer in the midst of their midday games and festivities while many were out on the daily hunt.

On June 25, 1876, the great camp was scattered for three miles or more along the level river bottom, back of the thin line of cottonwoods — five circular rows of teepees, ranging from half a mile to a mile and a half in circumference. Here and there stood out a large, white, solitary teepee; these were the lodges or “clubs” of the young men. Crazy Horse was a member of the “Strong Hearts” and the “Tokala” or Fox Lodge. He was watching a game of ring toss when the warning came from the southern end of the camp of the approach of troops.

The Indians now crossed the divide between the Tongue and the Little Big Horn, where they felt safe from immediate pursuit. Here, with all their precautions, they were caught unawares by General Custer in the midst of their midday games and festivities while many were out on the daily hunt.

The Sioux and the Cheyenne were “minute men,” and although taken by surprise, they instantly responded. Meanwhile, the women and children were thrown into confusion. Dogs were howling, ponies were running hither and thither, pursued by their owners, while many of the old men were singing their lodge songs to encourage the warriors or praising Crazy Horse’s “strong heart.”

That leader had quickly saddled his favorite war pony and was starting with his young men for the south end of the camp when a fresh alarm came from the opposite direction, and looking up; he saw Custer’s force upon the top of the bluff directly across the river. As quick as a flash, he took in the situation — the enemy had planned to attack the camp at both ends at once, and knowing that Custer could not ford the river at that point, he instantly led his men northward to the Ford to cut him off. The Cheyenne followed closely. Custer must have seen that incredible dash up the sage-bush plain, and one wonders whether he realized its meaning. In a very few minutes, this wild general of the plains had outwitted one of the most brilliant leaders of the Civil War and ended at once his military career and his life.

In this dashing charge, Crazy Horse snatched his most famous victory out of what seemed frightful peril, for the Sioux could not know how many were behind Custer. He was caught in his own trap. To the soldiers, it must have seemed as if the Indians had risen from the earth to overwhelm them. They closed in from three sides and fought until not a white man was left alive. Then they went down to Reno’s stand and found him so well entrenched in a deep gully that it was impossible to dislodge him. Gall and his men held him there until General Terry’s approach compelled the Sioux to break camp and scatter in different directions.

While Sitting Bull was pursued into Canada, Crazy Horse, and the Cheyenne wandered about comparatively undisturbed during the rest of that year. In the winter, the army surprised the Cheyenne but did not do them much harm, possibly because they knew that Crazy Horse was not far off.

His name was held in wholesome respect. From time to time, delegations of friendly Indians were sent to him to urge him to come into the reservation, promising a full hearing and fair treatment.

For some time, he held out, but the rapid disappearance of the buffalo, their only means of support, probably weighed with him more than any other influence. In July 1877, he was finally prevailed upon to come into Fort Robinson, Nebraska, with several thousand Indians, most of them Ogallala and Minneconwoju Sioux, on the distinct understanding that the government would hear and adjust their grievances.

At this juncture, General George Crook proclaimed Spotted Tail, who had rendered much valuable service to the army and was the head chief of the Sioux, who was resented by many.

The attention paid to Crazy Horse was offensive to Spotted Tail and the Indian scouts, who planned a conspiracy against him. They reported to General Crook that the young chief would murder him at the next council and stampede the Sioux into another war. He was urged not to attend the council and did not, but another officer was sent to represent him. Meanwhile, Crazy Horse’s friends discovered the plot and told him of it. His reply was, “Only cowards are murderers.”

His wife was critically ill at the time, and he decided to take her to her parents at Spotted Tail agency, whereupon his enemies circulated the story that he had fled and a party of scouts was sent after him. They overtook him riding with his wife and one other but did not undertake to arrest him. After he had left the sick woman with her people, he went to call on Captain Lea, the agent for the Brules, accompanied by all the warriors of the Minneconwoju band. This volunteer escort made an imposing appearance on horseback, shouting and singing. In the words of Captain Lea himself and the missionary, the Reverend Mr. Cleveland, the situation was highly critical. Indeed, the scouts who had followed Crazy Horse from Red Cloud agency were advised not to show themselves, as some of the warriors had urged that they be taken out and horsewhipped publicly.

Under these circumstances, Crazy Horse again showed his masterful spirit by holding these young men in check. He said to them in his quiet way: “It is well to be brave in the field of battle; it is cowardly to display bravery against one’s own tribesmen. These scouts have been compelled to do what they did; they are no better than servants of the white officers. I came here on a peaceful errand.”

The captain urged him to report to army headquarters to explain himself and correct false rumors. On his giving consent, he was furnished with a wagon and escort. It has been said that he went back under arrest, but this is untrue. Indians have boasted that they had a hand in bringing him in, but their stories are without foundation. He went of his own accord, either suspecting no treachery or determined to defy it.

When he reached the military camp, Little Big Man walked arm in arm with him, and his cousin and friend, Touch-the-Cloud, was just ahead.

After they passed the sentinel, an officer approached them and walked on his other side. He was unarmed but for the knife, which is carried for ordinary uses by women as well as men. Unsuspectingly, he walked toward the guardhouse when Touch-the-Cloud suddenly turned back, exclaiming: “Cousin, they will put you in prison!”

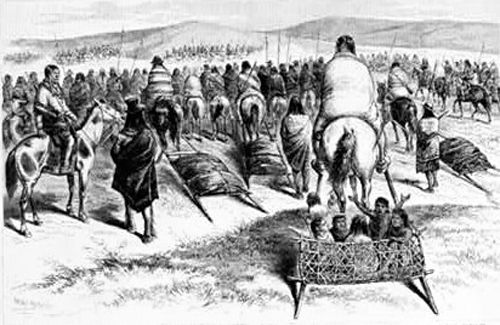

Crazy Horse leads his band in surrender.

“Another white man’s trick! Let me go! Let me die fighting!” cried Crazy Horse. He stopped and tried to free himself and draw his knife, but both arms were held fast by Little Big Man and the officer. While he struggled thus, a soldier thrust him through with his bayonet from behind.

The wound was mortal, and he died in the course of that night, his old father singing the death song over him and afterward carrying away the body, which they said must not be further polluted by the touch of a white man. They hid it somewhere in the Bad Lands, his resting place to this day.

Thus died one of the ablest and truest American Indians. His life was ideal; his record was clean. He was never involved in any of the numerous massacres on the trail but was a leader in practically every open fight. Such characters as those of Crazy Horse and Chief Joseph are not easily found among so-called civilized people. The reputation of great men is apt to be shadowed by questionable motives and policies, but here are two pure patriots, as worthy of honor as any who ever breathed God’s air in the vast spaces of a new world.

Though Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa) doesn’t specifically say so, Crazy Horse was a member of the Ogallala Lakota tribe, a band of the Sioux. He died on September 5, 1877.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025. Excerpted from the book Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains by Charles A. Eastman, 1918. The text as it appears here, however, is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clarity and ease for the modern reader. Charles A. Eastman earned a medical degree from Boston University School of Medicine in 1890 and then began working for the Office of Indian Affairs later that year. He worked at the Pine Ridge Agency, South Dakota, and was an eyewitness to both events leading up to and following the Wounded Knee Massacre of December 29, 1890. He was part Sioux, and he knew many of the people about whom he wrote.

Also See:

Charles Alexander Eastman – Sioux Doctor, Author & Reformer

Native American Heroes and Leaders