Civil War in Oklahoma.

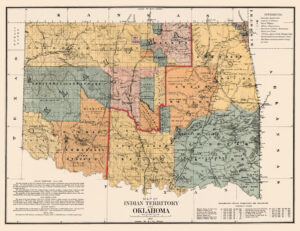

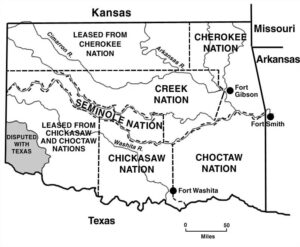

During the Civil War, most of what is now the U.S. state of Oklahoma was designated as the Indian Territory. It was an unorganized region set aside expressly for Native American tribes. It was primarily occupied by tribes removed from their ancestral lands in the Southeastern United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830. As part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Indian Territory was the scene of numerous skirmishes and seven officially recognized battles involving both Native American units allied with the Confederate States of America and Native Americans loyal to the United States government, as well as other Union and Confederate troops.

Before the outbreak of the Civil War, the United States government relocated all soldiers in the Indian Territory to other key areas, leaving the territory unprotected from Texas and Arkansas, which had already joined the Confederacy.

The Confederate government, formed in early February 1861, had plans for the West. Jefferson Davis and his councilors saw the need to protect the Mississippi River, use the western Confederacy as a “breadbasket” in the event of a Union blockade, a buffer between Texas and the Union-held Kansas, and eventually establish Indian Territory as a springboard for Westward Expansion.

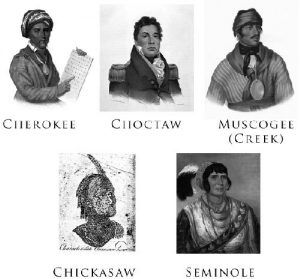

After the war began, Confederate officers negotiated with Native American tribes in the Indian Territory for combat support in June and July 1861, offering them protection, economic resources, and sovereignty. Most tribal leaders aligned with the Confederacy, including the Five Civilized Tribes: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations. Other tribes also signed treaties of alliance with the Confederate States of America, including the Comanche, Osage, Quapaw, Seneca–Cayuga, and the Shawnee. Troops were raised under the leadership of General Douglas H. Cooper, and Confederate forces took possession of the U.S. Army forts in the area.

At least 7,860 Native Americans participated in the Confederate Army as both officers and enlisted men.

After refusing to allow Creek lands to be annexed by the Confederacy, Creek Chief Opothle Yahola led the Creek supporters of the Union to Kansas, having to fight along the way. Leaders from each of the Five Civilized Tribes, acting without the consensus of their councils, agreed to be annexed by the Confederacy in exchange for certain rights, including protection and recognition of current tribal lands.

After reaching Kansas, Opothle Yahola and his loyal Union followers formed three volunteer regiments known as the Indian Home Guard to serve in the Indian Territory and occasionally in adjacent areas of Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Operations to Control Indian Territory

After abandoning its forts in the Indian Territory early in the Civil War, the Union Army was unprepared for the logistical challenges of trying to regain control of the territory from the Confederate government. The area was largely undeveloped relative to its neighbors: roads were sparse and primitive, and railroads did not yet exist in the territory. Pro-Union Indians had abandoned their farms because of raids by pro-Confederacy Indians and fled to Kansas or Missouri, seeking protection from better-organized Union forces there. The Union did not have enough troops to control the few roads, and sustaining a large military operation was not feasible by living off the land. This was demonstrated in 1862 when General William Weer’s “Indian Expedition” into the Indian Territory from Kansas met with disaster when food and supplies were quickly exhausted, and Union supply trains failed to arrive.

The first battle in the territory occurred on November 19, 1861. Muscogee Chief Opothle Yahola rallied Indians to the Union cause at Deep Fork. A total of 7,000 men, women, and children resided in his camp. A force of 1,400 Confederate soldiers under Colonel Douglas H. Cooper initiated the Battle of Round Mountain but were repulsed after several waves, leading to a Southern defeat. Opothleyahola then moved his camp to a new location at Chustenalah. On December 26, 1861, Confederate forces again attacked, this time driving Opothle Yahola and his people to Kansas on what became known as the Trail of Blood on Ice.

Confederate leaders attempted to use Indian Territory troops to force the Federals out of Arkansas. Under General Albert Pike, the Indian regiments joined divisions led by Brigadier Generals Sterling Price and Ben McCulloch to drive out Union troops under Brigadier General Samuel R. Curtis. However, at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862, Curtis proved the superior strategist and defeated the Confederate command. Pike, upset by McCulloch’s charges that the Indian troops had performed in a disorderly manner and had scalped Union soldiers, took his regiments back to Indian Territory and resigned. Stand Watie, who fought at Pea Ridge, and other officers operating outside the Indian Territory had to fight on without support.

Indian Expedition of 1862

In 1862, Union commanders in the West decided to seize Indian Territory. Union General James G. Blunt ordered Colonel William Weer to lead a Union Indian Expedition into the Indian Territory. Moving out of Kansas in June 1862, the expedition included five white regiments, two Indian regiments, two artillery battalions, and more than 5,000 men. The expedition’s main objective was to escort the Indian refugees who had fled to Kansas back to their homes in the Indian Territory. A secondary objective was to hold the territory for the Union. Colonel Weer’s expedition departed from Baxter Springs, Kansas, and met with early success at the Battle of Locust Grove in Indian Territory on July 3. There, the Union troops attacked units under Colonels Stand Watie and John Drew and defeated the Confederates by superior use of artillery.

The expedition camped at Locust Grove for two weeks, waiting for a Union supply train. One detachment from the main force moved on to Fort Gibson, causing the Confederates stationed there to withdraw. However, the Union supply train failed to arrive, and food, forage, and ammunition ran low. Not knowing what to do next, Weer found solace in drinking heavily. The men under his command soon mutinied, arresting Weer, putting Colonel Frederick Salomon in command, and bringing the expedition to an end before making any further progress into Indian Territory. The expedition encouraged the organization of three Indian Home Guard regiments supporting the Union.

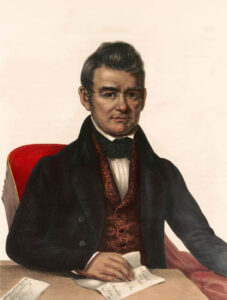

This failed expedition threw the Cherokee into turmoil. Chief John Ross used the occasion to negate the Confederate treaty and to embrace the Union cause. He and his family left the Cherokee Nation and resided in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C., for the remainder of the war.

On October 22, 1862, Union Brigadier General James G. Blunt invaded Indian Territory from Arkansas and defeated Colonel Douglas H. Cooper at Fort Wayne. Blunt made several quick attacks and placed Colonel William A. Phillips in charge of organizing Cherokee Unionists.

Second Indian Expedition of 1863

The Federal Second Indian Expedition in 1863 proved more successful than its predecessor. The expedition involved several battles and actions, including the capture of Fort Gibson, in which the Second Indian Home Guard helped drive Confederate defenders into the Grand River in April 1863. In July 1863, Indian Home Guard soldiers helped save a Union supply train from Stand Watie’s Confederate forces in the First Battle of Cabin Creek. On July 17, 1863, Union forces led by General Blunt, including Indian regiments, white soldiers, and African-American troops, defeated the Confederates under Confederate General Douglas H. Cooper at Honey Springs. In this, the most important military engagement in Indian Territory during the Civil War, the Union army was victorious due to superior artillery and inferior Confederate gunpowder.

Guerrilla Warfare

After the Battle of Honey Springs, the Civil War in Indian Territory assumed a different form, bringing endless raids and skirmishes as the region’s fate became similar to that of border areas like Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Rule of law was lost, and roaming bands of irregular partisans plundered and murdered hapless civilians.

Confederate Captain William Quantrill and his gang committed several raids throughout the lands of the Five Civilized Tribes. Armed gangs known as “free raiders” stole horses and cattle while burning the communities of both Confederate and Indian supporters.

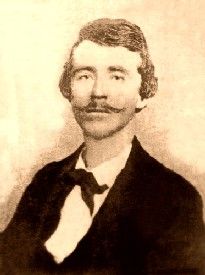

A third type of raider was the Confederate Army unit led by General Stand Watie, which attacked only objectives having military value. They destroyed houses and barns used by Union troops as headquarters, troops quarters, or storing supplies. Watie also targeted military supply trains, depriving Union troops of food, forage, and ammunition, and distributed significant amounts of booty to his men. His most famous exploits were the capture of the Steamboat J.R. Williams on June 15, 1864, and his seizure of a Union supply train at Cabin Creek on September 19, 1864. Watie and his troops surrendered at Doaksville on June 23, 1865. Later that year, he went to Washington, D.C., to negotiate on behalf of his tribe and sought recognition of a Southern Cherokee Nation. However, the U.S. government negotiated only with the Cherokee, who had supported the Union, naming John Ross as the rightful principal chief.

End of the War

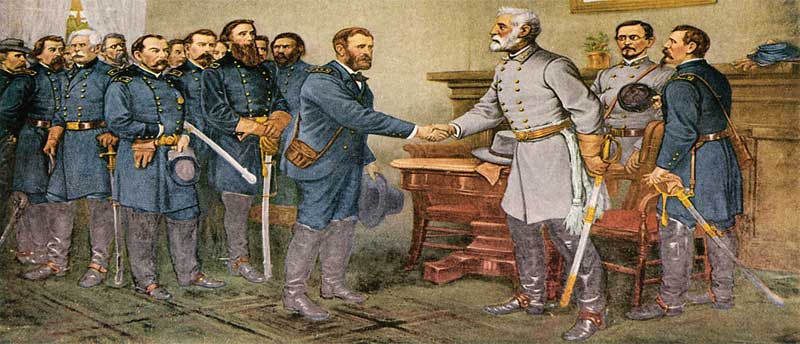

On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Virginia, sealed the Confederacy’s fate, but it was some time before Western generals accepted its demise. On May 26, 1865, Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered the Confederacy’s Trans-Mississippi Department, of which Indian Territory was a part.

Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Virginia, 1865 by Thomas Nast.

Stand Watie was one of the last Confederate generals to capitulate on June 23, 1865. At the end of the war, Confederate civilians, numbering nearly 15,000, gathered and suffered in camps around the Red River. It has been estimated that among the Cherokee, by 1863, one-third of the married women had become widows, and one-fourth of the children were orphans.

From the Oklahoma region, some 3,530 men had enlisted in the Union Army and 3,260 in the Confederacy. Approximately 10,000 people died due to the war. The loss of livestock and the end of slavery greatly affected the tribes’ economic systems.

Added to the misery of refugee camps was the systematic plundering of the tribes’ wealth.

As part of the Reconstruction Treaties, U.S. officials forced land concessions upon the tribes. It also required the Cherokee and other tribes to emancipate their slaves and give them full rights as members of their respective tribes, including annuities and land allocations.

The tribes unsuccessfully attempted to reclaim the advances made between 1840 and 1860. Although wartime animosities flared between the old Confederate and Union factions, new governmental entities were formed as a spate of constitution-making occurred between 1867 and 1872.

Lawlessness was rampant in the postwar years. The destruction of legal authority and infighting among the tribes made it difficult to police the region. In the absence of law enforcement, terrorists who had operated with impunity during the war returned to continue their rampaging ways—the James Gang, the Younger Gang, and the Dalton Brothers.

Railroads penetrated Oklahoma in the 1870s, but in some ways, their arrival was a curse rather than a blessing, for they brought hundreds of white settlers seeking land.

The Civil War weakened the tribes. It exacerbated long-standing internal divisions, made new ones, destroyed the needed population, and crushed economic advance. Without the war, the tribes might have grown in numbers, wealth, and political power. They might then have been better able to ward off later Euroamerican attacks on their land.

Later, the issue of citizenship caused contention when American Indian lands were allotted to households under the Dawes Commission in 1893. In the early 20th century, the Cherokee Nation voted to exclude the Freedmen from the tribe unless they also had direct descent from a Cherokee listed on the Dawes Rolls.

Oklahoma was officially admitted into the Union in 1907.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, January 2025.

Also See:

Soldiers & Officers in American History

Sources:

Cowsert, Zachery Christian, “Confederate Borderland, Indian Homeland: Slavery, Sovereignty, and Suffering in Indian Territory.” Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports, 2014.

Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Oklahoma Historical Society

Wikipedia