Chiricahua Apache

In one of the more infamous kidnappings of an American by a Native tribe, eleven-year-old Jimmy McKinn was abducted in 1885 and not found until 1886.

In 1875, all Apache west of the Rio Grande were forcibly relocated to the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona, a desolate and unforgiving region dubbed “Hell’s Forty Acres.” Deprived of their land, traditional rights, and adequate supplies, many Apache—led by Geronimo—revolted. Fleeing to Mexico, Geronimo and his followers launched intermittent raids against American settlements over the next decade, alternating with periods of peace at the reservation.

In 1882, General George Crook was sent back to Arizona to subdue the Apache. Though Geronimo surrendered in 1884, he fled again in May 1885, fearing execution. With 35 warriors and over 100 family members, he crossed into New Mexico, raiding settlements along the way.

In September 1885, Geronimo’s band reached the McKinn Ranch in the Mimbres Valley. John McKinn was away in Las Cruces, leaving behind his wife, daughter, and two sons—17-year-old Martin and 11-year-old Jimmy, also called Santiago. As the boys tended cattle, Geronimo’s group approached. They questioned Jimmy, then abducted him and some horses. When Martin asked about his brother, Geronimo struck him with a rock to silence him.

Martin’s body was found the next day. Distraught, John McKinn pursued the Apache for eight days, but returned empty-handed. The emotional toll led to a mental decline that lasted until his death 12 years later.

Initially, local newspapers incorrectly reported that both boys had been killed. Later accounts revealed that Jimmy might still be alive, having been taken captive by the Apache. Such abductions were common at the time—Indians and Mexicans alike often took children as slaves or future tribe members.

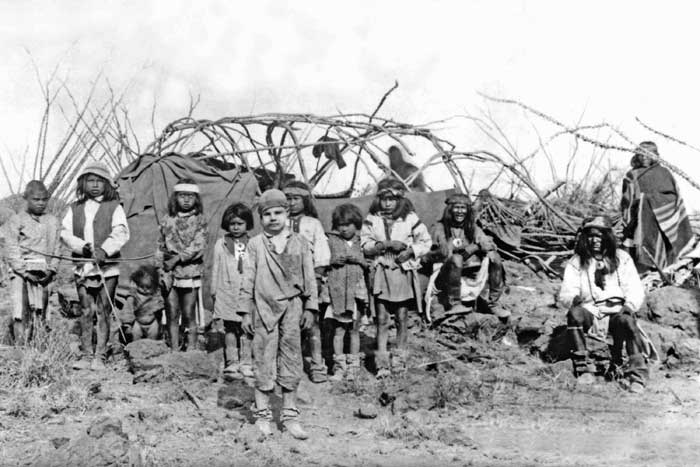

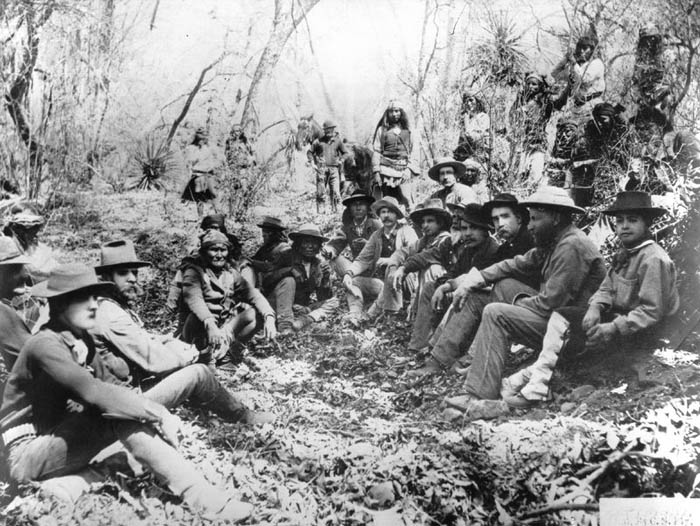

In March 1886, Crook’s forces caught up with Geronimo at Cañon de Los Embudos in Sonora, Mexico. Among the captured was young Jimmy McKinn. A reporter, Fletcher Lummis, and photographer C.S. Fly were present. Despite being told he would return to his family, Jimmy wept and pleaded to stay with the Apache. Fluent in Apache and resistant to English or Spanish, he had become fully “Indianized.”

Before the group could be returned to U.S. territory, Geronimo and several others escaped again. Crook was replaced by General Nelson Miles. Jimmy and the remaining captives were taken to Fort Bowie, Arizona.

From there, Jimmy was put on a train to Deming, New Mexico, where he was reunited with his father on April 8, 1886. He was sunburnt, dirty, and wary, but recognized his father immediately. He recounted the ordeal: his brother was killed by Geronimo, and he was forced to travel long distances, often going without rest or food, surviving primarily on horse meat. Despite harsh conditions, he was not mistreated and had even grown fond of his captors.

He provided valuable information about the Apache and their movements. Locals welcomed him warmly, and a merchant outfitted him with new clothes. Although initially reluctant to return to white society, Jimmy eventually resettled in Grant County, New Mexico. He later married, became a blacksmith, and moved to Phoenix, where he is believed to have died in the 1950s.

As for Geronimo, he was finally captured in September 1886 at Skeleton Canyon. He was imprisoned in Florida, later moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and became a symbol of both resistance and curiosity. He died in 1909, never returning to his homeland, and is buried in Fort Sill.

Geronimo surrenders to General Crook by Camillus S. Fly, 1886.

©Dave Alexander, Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Apache – The Fiercest Warriors in the Southwest

Cynthia Ann Parker – White Woman in a Comanche World

Geronimo – The Last Apache Holdout

Sources:

Eagan, Jerry; The Captive; Desert Exposure; November, 2006.

True West Magazine

Wikipedia