The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush in Colorado led to a great rush of people to the new El Dorado. Within no time, suitable routes to the Rocky Mountains were explored.

In 1858, John Beck, a member of the original Cherokee party of 1849-1850 that found gold in Ralston Creek several years earlier, became a principal promoter of a new expedition to the Rockies led by William Green Russell. A small group under Russell found gold in paying quantities on Cherry Creek in July, and news of the discoveries was soon broadcast far and wide.

John Cantrell of Westport, Missouri, visited the Cherry Creek diggings and brought back a bag of ore to Kansas City, reporting that seven members of his party “had made over $1,000 in ten days.”

This account was widely circulated, and soon Pike’s Peak gold fever gripped Kansas and Missouri.

“Not a day passes, but what a company may be seen starting from our city for Pike’s Peak.”

— The Leavenworth Times

With the prospect of a massive migration to the West, the “jumping off” points on the border began to vie with one another for a share of the business. Kansas City, Leavenworth, Atchison, Westport, and St. Joseph each argued its superiority as the best place to outfit emigrants.

In 1855, William H. Russell and Alexander Majors, who had been in the freighting business, formed a partnership and established headquarters at Leavenworth, Kansas, from where they transported supplies to Fort Laramie, Wyoming, and Fort Kearny, Nebraska. In 1858, if not earlier, William B. Waddell, a Missouri financier, joined the firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell and became known as the largest freight contractor for the government in the West.

In 1859, the “Parallel Road,” also known as the “Great Central Route,” along the 1st standard parallel through western Kansas and the gold regions of the Rocky Mountains, was laid out. This highway to the Cherry Creek diggings in Colorado was 469 miles long, 641 miles to Denver, and boasted an abundance of wood and water. It was laid out by E.D. Boyd, a civil engineer, in anticipation of heavy travel from the Missouri River to the new “diggings.”

On April 28, 1859, Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, announced “To the Friends of The Tribune” that he would be taking a trip westward through Kansas and the alleged Gold Region at the Eastern base of the Rocky Mountains.

On Monday, May 9, Greeley boarded the train at New York for his Western journey. He traveled the accustomed route: by train to Buffalo, then to Chicago and Quincy, Illinois. At Quincy, he took the boat down the Mississippi River as far as Hannibal, Missouri, where he again took the train over the Hannibal & St. Joseph railroad to St. Joseph. Here he took passage on the steamer Platte Valley for Atchison, Kansas, arriving on May 15.

On his trip to the new gold fields of Colorado in 1859, Horace Greeley described in flowery language the tremendous business of the organization, with its “acres of wagons… pyramids of extra axletrees… herds of oxen, and regiments of drivers and other employees.”

During the winter of 1859-1860, plans were made to establish one of the most noted transportation companies ever to serve the Rocky Mountains. William H. Russell and John S. Jones of the freighting firm Russell, Majors, and Waddell founded the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express Company. Over 50 Concord coaches were purchased for the line. Each of these coaches was drawn by four fine Kentucky mules, which were changed at stations established from 20 to 30 miles apart, according to the availability of wood and water. The route ran westward on the divide between the Republican and the Solomon Rivers.

| Stage Stations: | County | Information |

| Station 1 – Leavenworth, Kansas | Leavenworth |

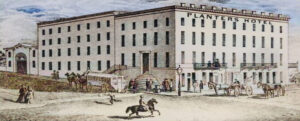

This station was in the basement of the Planter’s House. This fine four-story brick building with 100 guestrooms opened for business in December 1856. The Planter’s most distinguished guest was Abraham Lincoln when he visited Leavenworth and stayed at the hotel from December 3-7, 1859. It was located at 101 N Esplanade Street in Leavenworth. Horace Greeley described what he saw in 1859: Such acres of wagons( such pyramids of extra axletrees, such herds of oxen! Such regiments of drivers and other employees. No one who does not see can realize how vast a business this is, or how immense are its outlays as well as its income. I presume this great firm has at this hour $2,000,000 invested in stock, mainly oxen, mules, and wagons. (Last year employed 6,000 teamsters, and worked 45,000 oxen.) Of course, they are capital fellows-so are those at the fort-but I protest against the doctrine that either army officers or army contractors, or both together, may have power to fasten slavery on a newly organized territory under the guise of letting the people of such territories govern themselves. While at Fort Leavenworth, Greeley witnessed the departure of a great mule train filled with 160 soldiers’ wives and babies, on their way to join their husbands in Utah, from whom they had been separated for nearly two years. |

| Station 2 – Easton | Leavenworth | Horace Greeley described Easton as “a village of 30 to 50 houses.” |

| Station 3 – Osawkie | Jefferson | At the crossing of Grasshopper Creek. Horace Greeley described the town as “a state of dilapidation and decay, like a good many Kansas cities which figure largely on the map.” |

| Station 4 – Silver Lake | Shawnee | On the Potawatomii Indian reservation. Albert D. Richardson, a correspondent for the Boston Journal, stated that this station was kept by a half-breed Indian with whom he passed the night after a day’s journey of 68 miles from Leavenworth. |

| Station 5 – St. Mary’s | Pottawatomie |

The station was at the St. Mary’s Catholic Mission. Albert D. Richardson, a correspondent for the Boston Journal, stated: Passed St. Mary’s Catholic Mission, a pleasant, home-like group of log houses, and a little frame church, bearing the cross aloft, among shade and fruit trees in a picturesque valley. The mission has been in operation for 12 years. In the schoolroom, we saw 60 Indian boys at their lessons. |

| Station 6 – Manhattan | Riley | In Manhattan, Horace Greeley joined Albert D. Richardson, both bound for the gold mines. Due to high water, their express coach was delayed by a day. Here, Albert D. Richardson stated: Beyond the three houses that composed the town of Pittsburgh, we crossed the Big Blue River and reached Manhattan, where there was a flourishing Yankee settlement of 200 to 300 people in a smooth and beautiful valley. Thus far, I had been the solitary passenger. But at Manhattan, Horace Greeley, after a tour through the interior to gratify the clamorous settlers with speeches, joined me for the rest of the journey.

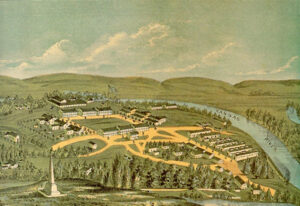

Henry Villard, a correspondent of the Cincinnati, Ohio, Daily Commercial newspaper, stated of this stop: The high, well-timbered bluffs of the Kansas River began to serve as a background to the scenery as we approached Manhattan… A short distance this side of Fort Riley, we came upon the ruins of Pawnee and Riley cities, consisting of two or three storehouses on both banks of the Kansas River, which were considered but a few years ago as the beginning of surely great cities. It was here that Governor Andrew Reeder wanted to locate the state capital, for the purpose of subserving the land interest he owned in this vicinity. But in this, as is well known, he signally failed, and the edifices mentioned above will stand as monuments of a speculation that overleaped itself. Fort Riley is the best military post I have seen upon my extensive travels through the West. Officers’ quarters, sutlers’ establishments, stables, etc., all have an appearance of solidity and cleanliness which differs greatly, and pleasingly to the eye, from the rudely constructed cabins of which the towns we had passed consisted. |

| Station 7 – Junction City. | Geary | At this point, Albert D. Richardson stated: We stopped for the night at Junction City, the frontier post office and settlement of Kansas.

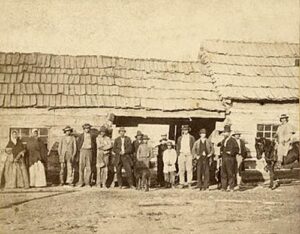

Henry Villard, a correspondent of the Cincinnati, Ohio, Daily Commercial newspaper, stated: Junction City, which is a combination of about two dozen frame and log houses, derives its name from being at the junction of the Smoky Hill and Republican Rivers… During my stay at Junction City, I paid a visit to the “Sentinel” office, the most westerly located newspaper establishment of eastern Kansas. Its office is a most original institution. It serves the purposes of a printing house, law office, land agency, and tailor shop. The followers of these different avocations appear to live, and sometimes to starve, together in unbroken harmony. From Leavenworth to Junction City, which represents Station No. 7, the express route is in the very best working order. I came through in 22 riding hours, which is a better time than even the oldest stage lines are able to make, and fared as well on the way as though I were making a pleasure excursion along a highway of eastern travel. After leaving Junction City, we at once entered upon the unmodified wilderness of the seemingly endless prairies that intervene between the waters of the Missouri River and the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. Villard also wrote a good description of the express route from this point westward: From Junction City to the last-mentioned place [Denver], the route is divided into four divisions of five stations each, so that Denver City figures as Station No. 27. The distance between the several stations averages 25 miles. Care has been taken to locate the stations on creeks, in order to furnish the necessary supply of wood and water. From 18 to 24 mules, under the charge of a station keeper, his assistant, and four drivers, are kept at each of them, to furnish relays for the coaches from the East as well as the West. The latter completes two to three stages in a day. Passengers obtain three meals a day and plenty of sleep in tents, which will soon give way to log and frame houses. The road is an excellent one… Water, grass, and timber, the indispensable necessities of the navigators… [of the plains] are plentiful throughout, with the exception of the valley of the Republican, the extremely sandy character of which renders it destitute of timber. For the 125 miles that the road follows its course, grass and water are, however, ample. |

| Station 8 – Chapman’s Creek | Dickinson | This station was located on the west side of Chapman’s Creek near the present-day Clay-Dickinson county line. A distance of 23 miles from Junction City, the express stage halted to change mules and to dine. In the absence of a house, two tents and a brush arbor furnished accommodations for from six to 15 people. There was a score of mules picketed about on the grass, and a rail pen for two cows.

The station keeper, his wife, and two small girls lived here. They had an excellent dinner of bacon, greens, good bread, apple sauce, and pie upon a snowy tablecloth. Little time was lost for refreshments, and the express was soon on the road again. While the trail was less cut up than in the east, the hills were steep since there were no bridges and causeways over the water-courses. That afternoon, the travelers saw their first antelope, several of them being within rifle shot of the stage. They crossed many old buffalo trails but saw no buffalo that day. Greeley noticed that the limestone had changed to sandstone, and that the soil was thinner and the grass less luxuriant. The furious rains running off without any obstruction had washed “wide and devious water-courses.” Here, Albert D. Richardson stated: Dined at Chapman’s Creek, in a station of poles covered with sailcloth, but where the host, superior to daily drenchings, gave us an admirable meal upon a snowy tablecloth.” Horace Greeley said: Our road bore hence north of west, up the left bank of Chapman’s Creek, on which, 23 miles from Junction, we halted at “Station 8,” at 11:00 a.m., to change mules and dine… There is, of course, no house here, but two small tents and a brush arbor furnish accommodations for six to 15 persons, as the case may be. A score of mules are picketed about on the rich grass; there is a rail-pen for the two cows… She [the station keeper’s wife] gave us an excellent dinner of bacon and greens, good bread, applesauce, and pie… The water was too muddy… [to] permit me to drink it. |

| Station 9 – Pipe Creek | Clay | On Pipe Creek, probably northeast of present Minneapolis. Here, the express stopped for the night during Greeley’s 1959 journey. Here, their hostess had two small tents, which she informed her guests were of little protection in a drenching rain, and that she and her two children might as well be on the prairie. A log house, however, was in the process of construction. After eating supper, the two newspaper men sat in the coach writing letters by lantern light to their respective newspapers. The vehicle was shaking with the strong wind, and it is possible that the Tribune printers found Greeley’s letter less legible than usual. This was his sixth “Overland Journey” letter to the Tribune. He wrote:

The violent rain and windstorm came that night as anticipated, but neither tents nor wagons were upset. The travelers rose early, breakfasted at six, and said goodbye to Pipe Creek with its fringe of low elms and cottonwoods. Greeley considered the soil good in this section of the state, but not equal to that of the eastern part. Their route kept on the ridges away from the bottoms and marshes. Still, occasionally, in crossing streams with steep banks and miry beds, they would become stalled, and an extra span of mules from the other express wagon would help pull them out. Albert D. Richardson stated: Stopped for the night at Station Nine, consisting of two tents. In the evening wrote newspaper letters in the coach by a lantern. At ten o’clock composed ourselves to sleep in the carriage to the music of howling wolves and heavy thunder: Days’ travel 68 miles [Greeley estimated it as 58 miles]. Horace Greeley said: We rose early from our wagon-bed this morning, had breakfast at six, and soon bade adieu to Pipe Creek, with its fringe of low elms and cotton woods, such as thinly streak all the streams we have passed today… We have crossed many streams today, all making south for Solomon’s Fork, which has throughout been from two to six miles from us on our left… The route has been from 50 to 200 feet above the bed of the Fork, keeping out of all bottoms and marshes, but continually cut by water courses… in one of which… we stalled until an extra span of mules was sent from the other wagon to our aid. |

| Station 10 – Solomon River | Cloud | Near the Solomon River and close to or a little west of the present-day Glasco.

Albert D. Richardson stated: Dined at Station 10, sitting upon billets of wood, carpet sacks, and nail-kegs while the meal was served upon a box. It consisted of fresh buffalo meat, which tastes like ordinary beef, though of coarser fiber and sometimes with a strong, unpleasant flavor. When cut from calves or young cows, it is tender and toothsome. Six weeks ago, not a track had been made upon this route. Now it resembles a long-used turnpike. We meet many returning emigrants who declare the mines a humbug, but pass hundreds of undismayed gold-seekers still pressing on. |

| Station 11 – Limestone Creek | Jewell | Located on Limestone Creek, probably a little south of the present village of Ionia. At this place, the “Parallel Road” west from Atchison joined the express road at a point 172 miles west of that city. From this point of intersection, which seems to have been a branch of Limestone Creek (termed “Dog Creek” by E.D. Boyd), the Parallel Road made use of the “right of way” of the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express. The field notes of E.D. Boyd, the stage company’s civil engineer and surveyor, gave a table of distances from the crossing of the Republican (near Scandia, Republic County) and provided a more exact picture of much of the route of the express company.

Boyd: From the crossing of the Republican, the course is due west, crossing five branches of Dog [probably Limestone] creek at intervals of three to six miles until we reach Station No. 11, 31 miles beyond the Republican, from which point the distances set down hereafter are computed. Station No. 11 is 172 miles west of Atchison and ten miles north. Albert D. Richardson stated: Spent the night at Station Eleven, occupied by two men who gave us bread and buffalo meat like granite. Day’s travel f56 miles. |

| Station 12 – Beaver Creek | Smith | Probably a little south of the forks of Beaver Creek, about seven miles southwest of present-day Smith Center.

Albert D. Richardson stated: At Station 12, where we dined, the carcasses of seven buffalo were half-submerged in the creek. Yesterday, a herd of 3,000 crossed the stream, leaping down the steep banks. A few broke their necks by the fall; others were trampled to death by those pressing on from behind. |

| Station 13 – Reisinger’s Creek | Phillips | Located close to Kirwin near the junction of Deer Creek and the Solomon River. At Reisinger’s Creek, Station 13, the express spent the night of May 30, 1859.

E.D. Boyd, the stage company’s civil engineer and surveyor, described the creeks and landscape of the area, mentioning chalk cliffs and a table mountain with monuments as a conspicuous landmark. Albert D. Richardson stated: After being mired in the same creek [probably a branch of Cedar Creek] for two hours, our vehicle was drawn out by the oxen of friendly emigrants. Spent the night at Station 13. Day’s travel, 56 miles. Horace Greeley said: I write in the station tent (having been driven from our wagon by the operation of greasing its wheels, which was found to interfere with the steadiness of my hastily-improvised table), with the buffalo visible on the ridges south and every way but north of us. |

| Station 14 | Norton? | About 12 miles southeast of present-day Norton and about four miles north of the North Fork of the Solomon River, it was on the Norton-Phillips county line.

E.D. Boyd described the last 15 miles as rough and rolling along a crooked road with no water or wood for the last 17 miles. Horace Greeley: As we left Station 14 this morning and rose from the creek bottom to the high prairie, a great herd of buffalo was seen in and around our road. A.D. Richardson: Today, we have been among prairie-dog towns, passing one more than a mile long. Some of their settlements are said to be 20 miles in length, containing a larger population than any metropolis on the globe… This evening, we supped on his flesh and found it very palatable, resembling that of the squirrel. |

| Station 15 – Prairie Dog Creek | Norton |

Stagecoach Station 15 in Norton County, Kansas, courtesy Kansas Tourism. On the 100th meridian at approximately the point where it crosses Prairie Dog Creek, about five miles southwest of present Norton. A.D. Richardson: We spent the night at Station 15, kept by an ex-Cincinnati lawyer who, with his wife, formerly an actress at the Bowery Theater, is now cooking meals and making beds for stage passengers on the great desert 300 miles beyond civilization. Our road, following the valley of the Republican River, is here 2,300 feet above sea level. The day’s travel was 56 miles. Horace Greeley: We have made 56 miles since we started about nine this morning, and our present encampment is on a creek running to the Republican River, so that we have bidden a final adieu to Solomon’s Fork, and all other affluents of the Smoky Hill branch of the Kansas River. We traveled on the “divide” between this and the northern branch of the Kansas River for some miles today and finally came over to the waters of that stream (the Republican), which we are to strike some 80 miles further on. We are now just halfway from Leavenworth to Denver, and our coach has been a week making this distance; so that with equal good fortune, we may expect to reach the land of gold in another week. |

| Station 16 – Nebraska | Red Willow | This station was probably northeast of the present-day Oberlin. Horace Greeley and the other stagecoach travelers stopped here on June 1 to change teams and dine. Just before reaching Station 17, where they were to spend the night, an accident caused Greeley slight injuries. As he related it, he and his fellow passenger were having a jocular discussion on the gullies into which the coach so frequently plunged, to their discomfort. When they arrived at the station, a woman there dressed Greeley’s wounds, and aside from being sore and lame for a few days, he was uninjured. This was the first accident to occur on the express line and resulted from a casualty for which neither driver nor company was to blame.

Station 17 was just over the line in present-day Nebraska, and from here the route ran slightly northwest to the Republican River. It returned to Kansas farther on and cut diagonally across present Cheyenne County and entered present Colorado. Here, the travelers encountered the wild Plains Indians. A band of Arapaho was encamped near the station, while most of the men were away on a marauding expedition against the Pawnee, while the remainder, with the women and children, were left in the lodges. Some 30 or 40 children were playing on the grass. These children, Greeley described as thorough savages with an “allowance of clothing averaging six inches square of buffalo skin to each, but so unequally distributed that the majority had a most scanty allowance.” After seeing several bands of Indians, he thought the Arapaho were the most numerous and the most repulsive. Horace Greeley: Dined at Station Sixteen, kept by a Vermont boy who has roamed over 27 States of the Union. Near it was encamped a party of Arapaho, with 30 or 40 children playing upon the grass. Those under four or five years were entirely naked. The older boys wore breech clouts of buffalo skin, and the girls were wrapped in robes or blankets. All were muscular and well developed. |

| Station 17 | Rawlins | On Beaver Creek, one-half mile southwest of Ludell.

E.D. Boyd, the stage company’s civil engineer and surveyor, stated: On the north bank of Sappa Creek. Descending an abrupt hill, our mules, terrified by meeting three savages, broke a line, ran down a precipitous bank, upsetting the coach… He [Greeley] was soon rescued from his cage and taken to Station 17, a few yards beyond, where the good woman dressed his galling wounds. Horace Greeley: We left this morning Station 17, on a little creek entitled Gouler, at least 30 miles back [from Station 18}, and did not see a tree and but one bunch of low shrubs in a dry water course throughout our dreary morning ride, till we came in sight of the Republican, which has a little-a very little-scrubby cottonwood nested in and along its bluffs just here… Of grass, there is little, and that little of miserable quality… Soil there is none but an inch or so of intermittent grass-root tangle. The dearth of water is fearful. Although the whole region is deeply seamed and gullied by water-courses, now dry, but in rainy weather, mill streams, no springs burst from their steep sides. We have not passed a drop of living water in all our morning’s ride. Even the animals have deserted us. SITE OF STATION NO. 17 – This was one of the stations used by the Pikes Peak Express stagecoach on the trial from Leavenworth, Kansas, to Denver and the Pikes Peak area. In June 1859, the coach upset near Station NO. 17 – the passenger was Horace Greeley, who was treated at the station. |

| Station 18 – Benkelman, Nebraska | Dundy | This station was probably just below the forks of the Republican River, near present-day Benkelman, Nebraska.

E.D. Boyd: Leaving the waters of the Solomon River, we struck over to those of the Republican River. We struck Prairie Dog, Sappa, and Cranmer’s Creeks, near their head, then traveling a long divide of 26 miles, we reached the main Republican River, just above the mouth of Rock Creek, and made Station No. 18 in a beautiful grove of cottonwoods. After leaving No. 18, we continued on the southern side of the Republican River to near its head. Horace Greeley: For more than 100 miles back, the soil has been steadily degenerating, until here, where we strike the Republican River, which has been far to the north of us since we left it at Fort Riley, 300 miles back, we seem to have reached the acme of barrenness and desolation. I would match this station and its surroundings against any other scene on our continent for desolation. From the high prairie over which we approach it, you overlook a grand sweep of treeless desert, through … which flows the Republican… |

| Station 19 – Republican River | Cheyenne | This station was on the south bank of the Republican River, where there was no timber. It was probably a few miles northeast of the present St. Francis, Kansas. This was the last station on the route in present-day Kansas.

A.D. Richardson: We continued by the sandy valley of the Republican, destitute of trees and shrubs and barren as the Sahara. Spent the night at Station 19. The day’s travel was 64 miles. Horace Greeley: A large Cheyenne village is encamped around Station 19, where we stopped last night, and we have been meeting squads of these and other tribes several times a day. The Kiowa are camped some eight miles from this spot. They all profess to be friendly, though the Cheyenne have twice stopped and delayed the express-wagons on the pretence of claiming payment for the injury done them in cutting wood, eating grass, scaring away game, etc. They would all like to beg, and many of them are not disinclined to steal. |

| Station 19 – State Line | Cheyenne |

On the South Fork of the Republican River in Cheyenne County, probably near the present-day Colorado line and about eight miles northeast of what is now Hale, Colorado. |

| Station 20 | Kit Carson | E.D. Boyd: On the bank of the Republican River; no timber. The branch runs north, offering good water and a few cottonwood trees. |

| Station 21 – Tuttle | Kit Carson | On the South Fork of the Republican River, near the old town of Tuttle in Kit Carson County, Colorado (Probably below the Tuttle ranch.)

E.D. Boyd: On the bank of the Republican River with no timber. It has been suggested to make a cut-off from stations 17 to 21. It is thought that water and perhaps timber can be found at no great distance apart. The branches that we cross, though dry at the Republican River, have water in them above. Dug three feet deep in the bed of the Republican River; no water. Horace Greeley: The bottom of the river is perhaps half a mile in average width. Water is obtained from the apology for a river, or by digging in the sand by its side; in default of wood, corrals are formed at, the stations by laying up a heavy wall of clayey earth flanked by sods, and thus excavating a deep ditch on the inner side, except at the portal, which is closed at night by running a wagon into it. The tents are sodded at their bases; houses of sods are to be constructed so soon as may be. Such are the shifts of human ingenuity in a country that probably has not a cord of growing wood to each township of land. Six miles farther up, the stream disappears in the deep, thirsty sands of its wide bed and is not seen again for 25 miles. A.D. Richardson: At Station 21, where we spent the night, we first encountered fresh fish upon our table. Here, the enormous catfish of Missouri and Kansas has dwindled to the little horned pout of New England, lost its strong taste, and regained its legitimate flavor. The day’s travel was 59 miles. We still follow the Republican, which at one point sinks abruptly into the earth, running underground for 20 miles and then gushing up again. We saw one thirsty emigrant digging in the dry bed for water. At the depth of four or five feet, he found it. |

| Station 21 – Tuttle | Kit Carson | On the South Fork of the Republican, near the old town of Tuttle, in Kit Carson County. It was probably below the Tuttle Ranch. |

| Station 22 | Kit Carson | About five miles northwest of Seibert, Colorado, at the junction of the express road and a branch of the Smoky Hill Trail to Denver, by way of the Platte River.

E.D. Boyd: On the south bank of the Republican River, a large spring in the bed of the river, which sinks immediately below. Since first striking the Republican River, our course has been parallel with it, and our road nearly level. For the last 23 miles, there is no wood or water, but the grass is good. In that distance, there are some five miles of deep sandy road. The Smoky Hill route comes in from the southeast, and the South Fork Republican comes in from the southwest. Conglomerate Bluff to the right. N. Fork Republican ¾ mile north. South Fork Republican, 1½ miles south. Cross North Fork of Republican; dry, sandy bed 30 yards wide, with occasionally a spring; runs north-east; good grass. For the last 13 miles, high rolling prairie, little grass, and no water; good hard road. A.D. Richardson: After riding 25 miles without seeing a drop of water, at Station 22, we crossed the Smoky Hill Trail, which, from a point far south of ours, abruptly turns northward across the Republican River to the Platte River. Emigrants who have come by the Smoky Hill tell us they have suffered intensely, one traveling 75 miles without water. Some burned their wagons, killed their famishing cattle, and continued on foot. We are still in the desert with its soil white with alkali, its stunted shrubs, withered grass, and brackish waters often poisonous to both cattle and men. Day’s travel 40-eight miles. Horace Greeley: At Station 22, there is a so-called spring, and one or two considerable pools, not visibly connected with the sinking river, but doubtless sustained by it. And here the thirsty men and teams which have been 25 miles without water on the Express Company’s road, are met by those which have come up the longer and more southerly route by the Smoky Hill Trail, and which have traveled 60 miles since they last found water or shade… The Pike’s Peakers from the Smoky Hill, whom I met here, had driven their ox-teams through the 60 miles at one stretch, the time required being two days and the intervening night. From this point westward, the original Smoky Hill route is abandoned for the one we had been traveling, which follows the Republican some 25 miles further. The bluffs are usually low, and the dry creeks which separate them are often broad reaches of heavy sand… There is little grass on the rolling prairie above the bluffs… Some of the dry-creek valleys have a little that is green but thin, while the river bottom, often half a mile wide, is sometimes tolerably grassed, and sometimes sandy and sterile. Of wood, there is none for stretches of 40 or 50 miles: the corrals are made of earth, and consist of a trench and a mud or turf wall; one or two stationhouses are to be built of turf if ever built at all; and at one station the fuel is brought 60 miles from the pineries further west. |

| Station 23 – Hugo | Lincoln | On the South Fork of the Republican River, about 16 miles east and a little north of present-day Hugo, Colorado.

E.D. Boyd: On the north bank of the Republican, springs in bed, limestone and conglomerate crop out of a bluff on the south side of the Fork for the last 15 miles. Pike’s Peak in view, bears south about 70 degrees. Henry Villard, a correspondent of the Cincinnati, Ohio, Daily Commercial newspaper, stated: And last, but not least, a full aspect of the veritable snow-browed Pike’s Peak, which becomes already visible at station 13, a distance of 100 miles. It first looks like a cloud, but, as one comes nearer, assumes more precise and greater dimensions, and when arriving on the last ridge before running down into the Cherry Creek valley, its eastern front is completely revealed to the eye, together with a long chain of peaks, partly covered with snow and partly with pine, and extending in a northward direction as far as Long’s Peak. I have seen the Alps of Switzerland and Tyrol, the Pyrenees and Apennines. Yet, their attractions appear to dwindle into nothing when compared with the at once grotesque and sublime beauty of the mountain scenery upon which my eyes feasted before descending into the valley above referred to. |

| Station 24 – Big Sandy | Lincoln | About seven miles northwest of Hugo, Colorado, it was on the south fork of Big Sandy Creek.

E.D. Boyd: Big Sandy Creek runs southeast for some distance; a dry sandy bed 80 yards. Wide with pools of water at this point, with no timber. Horace Greeley: A ride over a rolling “divide” of some 20 miles brought us to the “Big Sandy,” running south-west to become a tributary (when it has anything to contribute) to the Arkansas River. Like the Republican River, it is sometimes a running stream, a succession of shallow pools, a waste of deep, scorching sand. A few paltry cottonwoods, a few bunches of low willow, may have graced its banks or those of some dry creek running into it, in the course of the 20 miles or so that we followed up its northern bank. I recollect only that the grass at intervals along its narrow bottoms seemed a little better than on the upper course of the Republican. One peculiarity of the Big Sandy I had not before observed-that of a thin, alkaline incrustration, mainly of soda, I believe-covering many acres of the smoother sands in its dry bed. |

| Station 24 – East Bijou Creek | Elbert | Located on the west bank of East Bijou Creek about five miles southwest of Godfrey, in Elbert County, Colorado.

E.D. Boyd: Creek, dry sandy bed 60 yards wide; runs north into the South Fork of Platte River, water by digging two feet; a few willows and cottonwood. |

| Station 25 – Beaver Creek | Elbert | It was at the top of a sandstone hill, with a fine view of Long’s Peak as well as Pike’s Peak.

E.D. Boyd: A branch runs north with pools of good water. Beaver Creek has a sandy bottom, is 12 yards wide, and has very good water; it also has a few scattered, small cottonwood and willows. Albert D. Richardson: At our dining station, I met several old Kansas acquaintances, so dust-covered and sunburnt that for several minutes I did not know them… Toward evening, Pike’s Peak loomed up grandly in the southwest, wrapped in its ghostly mantle of snow and streaked by deep-cut gorges shining in the rays of a blazing sunset. In the northwest, Long’s Peak was sharply defined against a mass of ominous black clouds, which rising slowly left behind them a scattered trail, dark and wild as the locks of the storm god. Horace Greeley: At length, we crossed its deep, trying sand and left it behind us Big Sandy Creek, passing over a high “divide” much cut up by gullies through which the water of the wet seasons tears its way to the Arkansas on the south or the Platte River on the north, until we struck, at five last evening, the first living tributary to the Platte-a little creek called Beaver. It is about ten miles east of the Bijou, with which it probably unites before reaching the Platte. After leaving the valley of Big Sandy, the grass of the uplands becomes better and is no longer confined to the water-courses. At Beaver Creek, we saw, for the first time in many weary days, for more than 200 miles at the least, a clump of low but sturdy cotton-woods, 30 or 40 in number… And, six or seven miles further, just as night was falling, we came in sight of pines, giving double assurance that the mountains were at hand. |

| Station 26 – Kiowa Creek | Elbert | Probably on Kiowa Creek, about ten miles north of the present Kiowa, Colorado.

E.D. Boyd: Located on Kiowa Creek, ten feet wide, sandy bed, very shoal, good water, runs north; willow bushes; groves of pine Albert D. Richardson: Supping at Station 26, we made a comfortable bed in the coach, and rolling on at the rate of seven miles an hour, slept quietly through the night. |

| Station 27 – Denver | Arapahoe | Albert D. Richardson: Woke at five, still in motion, and obtained a glorious view of the mountains, their hoary peaks covered with snow and their base, 30 miles across the valley into which we were descending, seeming not more than two miles away. At last, we struck the old trail from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Salt Lake City, Utah, and rode a mile along the dry bed of Cherry Creek, and at eight this eleventh morning reached Denver City… During our journey from Leavenworth, we have doubtless passed 10,000 emigrants.

Horace Greeley: From the Bijou to Cherry Creek-some, some 40 miles, I can say little of the country, save that it is high rolling prairie, deeply cut by several streams, which run north-easterly to join the Platte River, or one of its tributaries just named. We passed it in the night, hurrying on to reach Denver, and at sunrise this morning, stopped to change mules on the bank of Cherry Creek. As to gold, Denver is crazy. She has been low in the valley of humiliation, and is suddenly exalted to the summit of glory. The following Denver Dispatch (dated June 4) of the St. Louis, Missouri Republican gives an account of the Denver office of the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express Company. For the first two weeks after the opening of the express office in this place, it occupied a log cabin of a rather primeval description. A few days ago, however, the headquarters were removed to a more civilized abode, consisting of a frame and affording a plentiful supply of light, of which the former windowless haunt had been entirely destitute. The express company carries, as you are undoubtedly already aware, the United States mail, and its mail department is a branch of its business, of great importance, extent, and profit. It is under the superintendency of Mr. Martin Field, formerly of the St. Louis, and lately of the Leavenworth City post office. Although recently arrived, he has already succeeded in systematizing the discharge of his onerous duties, and his office now presents that perfect mechanism that alone is apt to secure satisfaction to the public in mail matters. The post office is, of course, a place of general rendezvous; crowds of emigrants and immigrants, diggers, traders, mountaineers, etc., can always be seen in and about it, retelling their hopes and disappointments. |

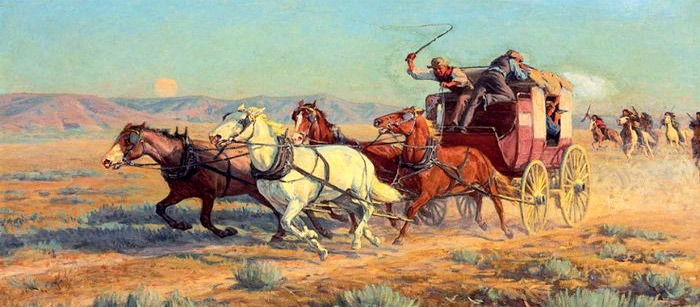

Stagecoach Painting by Richard Lorenz.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, August 2025.

Also See:

Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express Company

Stagecoaches of the American West

Sources:

Kansas Historical Society- Pike’s Peak Express Companies – 1

Kansas Historical Society- Pike’s Peak Express Companies – 2

Caldwell, Martha B.; Kansas Historical Quarterly, May 1940