Osage Chiefs in Indian Territory.

[The primary content for this article is an edited rendition of the Osage Indians as told in William G. Cutler’s History of the State of Kansas, first published in 1883.]

Of the Indian nations living north of the Arkansas River and west of the Mississippi River, the Osage were best known to the French during the early years of their occupancy of Louisiana. Claiming lands extending east even to the banks of the Mississippi River and maintaining friendly intercourse with the Illinois tribe, who dwelt on the opposite shore, the Osage were brought in frequent contact with the French adventurers of Kaskaskia, Natchez, and New Orleans. Rumors of mines of silver and lead to the west of the Mississippi River brought, at a very early day, many explorers into that region, and the discovery of the “Mine of the Marameg” by Sieur de Lichens in 1719, followed by the arrival of a large company of the King’s miners, under the superintendence of M. Renandiere, to construct furnaces and develop the mine, gave a fresh impetus to the prevailing spirit of extravagant expectation in regard to the mineral resources of the western portion of Louisiana.

At this time, the Osage had villages on the Missouri and Osage Rivers, the latter not very distant from the famous mine. Parties in search of silver and lead thoroughly explored their country, and to a comparatively late day, the extensive “diggings” on the old Osage Trail near the Le Mine River bore the marks of the spade and pick of the early French explorers.

It was during the year that silver was discovered on the Marameg, and when the mining mania was at fever heat, that Du Tissenet was sent by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, Governor of Louisiana, to explore the western part of the province and in the course of his investigations, visited and crossed from southeast to northwest to the present State of Kansas. Du Tissenet visited the village of the Osage Indians, five miles from the Osage River, at eighty leagues above its mouth, and describes the inhabitants as stout, well-made, and great warriors. He also mentions the lead mines that were found in their country.

Sixty-four Osage Indians formed a part of the escort of Etienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont, on his Pacific Mission to the Padoucas in 1724. Still, from that time, there has been no record of any organized French expeditions that visited the region. The destruction of Fort Orleans, of which De Bourgmont was Commandant, and the massacre of the entire garrison effectually put a stop, for a long time, to any further attempts to extend French exploration toward the west, and, except the fact that the Osage, Kanza, and Pawnee were engaged in continual war among themselves and with the more western tribes, little is known of them until the explorations of Lewis and Clark and Lieutenant Zebulon Pike furnished more definite knowledge of their locations, homes, and habits of life.

As early as 1796, a division was effected in the Osage Nation. The Chaneers, or Arkansas band, under the leadership of Chief Cashesegra, or Clermont, removed to the Verdigris River and formed several villages along its banks; that of Clermont is about 60 miles up the river. The Arkansas band was principally composed of the young men of the two tribes, and its formation was effected through the influence of Pierre Choteau, a St. Louis fur trader, who had hitherto enjoyed a monopoly of the trade with the Osage by way of the river of the same name. Having been superseded as the agent by Manuel de Lisa, also an enterprising St. Louis trader, Choteau determined to plant a colony of young and vigorous Osage on one of the tributaries of the Arkansas River and endeavor to draw the trade of his rival to the more southern river, in which financial scheme he was pretty successful, the new settlement soon entirely overshadowing the older.

About 1803, the Little Osage separated from the Grand Osage and made a village on the Missouri River, near where Fort Clark, afterward called Fort Osage, was built. They, however, were soon attacked by the warlike tribes farther to the north and east and forced to seek refuge and protection in the vicinity of the more numerous band of the Grand Osage, who dwelt near the headwaters of the Osage River, about 15 miles east of the present Kansas line.

One of the objectives of Lieutenant Zebulon Pike’s expedition of 1806 and 1807 through the interior of Louisiana was to deliver at the village of Grand Osage several Osage captives, lately prisoners, in the hands of the Pottawatomie. Another was “the accomplishment of a permanent peace between the Osage and Kanza, and a third was to endeavor to make peace between the Comanche and Osage.

In accomplishing these objectives, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike had the opportunity to observe the customs and noted the peculiarities of the Osage at that period. At the time of his arrival at the village of the Grand Osage, the Little Osage had already marched a war party against the Kanza and the Grand Osage, a party against the Arkansas band. White Hair, chief of the Grand Osage, was unable to prevent it, although the expedition was contrary to his wishes. Schemers at St. Louis were constantly inciting trouble between the tribes and turning their quarrels to their advantage. The treaty of peace, which Lieutenant Pike was instrumental in bringing about, was faithfully observed by both Osage and Kanza.

At the time of this visit, the Grand Osage village on the Osage River numbered, by actual census — men, 502; boys, 341; women and girls, 851; lodges, 214. Cheveau Blanc, or White Hair, was the chief. The Little Osage numbered 824, and Clermont’s band, 1,500. The government was nominally vested in a small number of chiefs. Still, their power was limited, and all measures they proposed were submitted to a council of warriors and decided by a majority vote.

The tribe was divided into two classes: warriors and hunters comprised the first, and cooks and doctors comprised the second. The doctors were also priests or magicians, possessing great influence. They were supposed to have knowledge of deep mysteries and to be wonderfully skilled in the use of medicines. The cooks were also of much importance, the class including all the warriors who, from age or other cause, were unable to join the war parties.

When received into an Osage village, a guest immediately presented himself at the lodge of the chief, where he was expected to eat his first meal, after which he was invited to a general feast given by the most important warriors and great men. The cooks stood outside the lodge and gave the invitation by crying, in a loud voice: “Come and eat; such a one gives a feast.” The feasts were repeated until all the more important members of the tribe had an opportunity to display their hospitality.

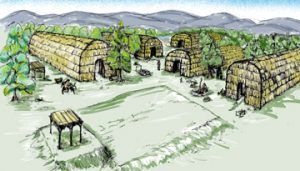

Indian Lodge.

The Osage lodges were usually constructed by driving upright posts about 20 feet high into the ground. The posts had crotched tops to rest on the ridge pole, over which were bent small poles fastened to stakes about four feet high.

The ends of the lodge were formed by broad slabs, and the whole was covered with rush matting. There was generally a door on each side, the fire being in the center, with a hole in the roof for the escape of the smoke. A raised platform covered with skins at one end served to display the household treasures of the host and as a place of honor for the guests. The lodges varied in length from thirty-six to one hundred feet.

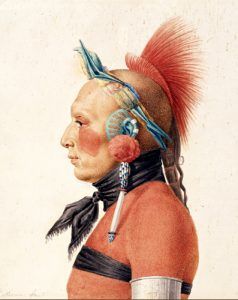

Physically, the Osage were the finest specimens of Western Indians — tall, erect, and dignified. The average height of the men was over six feet.

On November 10, 1808, a few years after the United States acquired Louisiana, a treaty was made at Fort Clark, which had recently been built on the Missouri River between the United States and the Osage Nation.

Article 1 of the treaty reads as follows:

“The United States, being anxious to promote peace, friendship, and intercourse with the Osage tribes, to afford them every assistance in their power, and to protect them from the insults and injuries of other tribes of Indians situated near the settlements of the white people, have thought proper to build a fort on the right bank of the Missouri, a few miles above the fire prairie, and do agree to garrison the same with as many regular troops as the President of United States may, from time to time, deem necessary for the protection of all orderly, friendly and well disposed Indians of the Great and Little Osage Nations who reside at this place, and who do strictly conform to and pursue the counsels or admonitions of the President of the United States through his subordinate officers.”

At Fort Clark, the United States agreed “to establish and permanently to continue, at all seasons of the year, a well-assorted store of goods “for the purpose of bartering with the Osage, on moderate terms, for their peltries and furs; also “to furnish at this place, for the use of the Osage Nations, a blacksmith, and tools to mend their arms and utensils of husbandry, and engage in building them a horse-mill, or water-mill; also to furnish them with plows, and to build for the great chief of the Great Osage, and for the great chief of the Little Osage, a strong blockhouse in each of their towns, which are to be established near this fort.”

There was also, by the terms of the treaty, to be delivered annually to the Great Osage Nation merchandise to the value of $1,000 and the Little Osage Nation merchandise to the value of $500. In addition, there was to be paid, at or before the signature of the treaty, to the Great Osage Nation the sum of $800 and to the Little Osage Nation the sum of $400.

Article 6 of the treaty reads as follows:

“And in consideration of the advantages which we derive from the stipulations contained in the foregoing article, we, the chiefs and warriors of the Great and Little Osage, for ourselves and our nation respectively, covenant and agree with the United States, that the boundary line between our nations and the United States shall be as follows, to wit: Beginning at Fort Clark, on the Missouri River, five miles above Fire Prairie, and running thence a due south course to the river Arkansas and down the same to the Mississippi, hereby ceding and relinquishing forever to the United States all the lands which lie east of the said line, and north of the southwardly bank of the said river Arkansas and all lands situated northwardly of the Missouri River. And we do further cede and relinquish to the United States forever, a tract of two leagues square, to embrace Fort Clark, and to be laid off in such manner as the President of United States shall think proper.”

Pierre Choteau.

According to his report, in 1804, President Thomas Jefferson promised the Osage chiefs, then, on a visit to Washington, that they would establish a trading post for the benefit of their nation. This promise was repeated in 1806. The fort was built in October 1808, and the following month, November 8, 1808, Pierre Chouteau, United States Agent for the Osage, arrived at Fort Clark, prepared to execute the treaty which Governor Lewis of Missouri had deputized him to offer the nation. The chiefs and warriors of the Great and Little Osage assembled on November 10 and, upon learning that the trading post, which was supposed by them to have been established as a favor and mark of friendship, was, in fact, a part of the price paid for their lands, and that, unless they accepted the provisions of the treaty, they virtually forfeited the protection of the United States, they reluctantly signed it, protesting that “they had no choice; they must either sign the treaty or be declared the enemies of the United States.”

This treaty was not ratified by the Senate until 1810, and the Indians did not receive the first annuity until September 1811, three years after the treaty was made. The blockhouse, which was promised for the defense of the Osage towns on the Osage River, was useful only to the traders, being detached from the agency and no competent person having charge. A mill was built, and a blacksmith was sent to the town of the Great Osage.

By the terms of the treaty of 1808, the Osage title to all land in Missouri was extinguished, except a strip 24 miles wide lying eastward from the western boundary of the State and extending from the Missouri River south into the Territory of Arkansas. The eastern line extended a few miles east of Fort Clark, which was situated on a bluff on the Missouri River near the present site of the town of Sibley. The principal village of the Osage was due south from the fort, on the Osage River, and it was this that Captain Zebulon Pike visited and described in 1806.

George Sibley, former commandant at Fort Clark, in his report, commended the Osage for their uniform and constant faithfulness to the French and Americans. They offered their services to him when in command of Fort Clark when British emissaries attempted to engage them in their service and declared their determination “never to desert their American father as long as he was faithful to them.” He says that “of all the Missouri Indians, they were the least accessible to British influence.”

Osage Indians by George Catlin.

At about the time of this report, a portion of the Osage Nation moved from the old location on the forks of the Osage River and settled on the bank of the Neosho River in the present county of Labette.

In 1817, the Cherokee attacked the Osage village on the Verdigris River during the absence of Clermont and his warriors, fired the town, destroyed the crops, and took prisoners, which included 50-60 old men, women, and children who were left there. This assault was followed by mutual acts of recrimination between the hostile tribes, resulting in war, which lasted several years, with the Delaware joining the Cherokee as allies. A treaty of peace between the contending nations was concluded at Belle Point in 1822.

The Osage Nation, in 1818, paid for property taken from citizens of the United States “by war parties and other thoughtless men of their several bands,” and being destitute of funds to do that justice to the citizens of the United States, which is calculated to promote a friendly intercourse, have agreed, and do hereby cede to the United States, and forever quit claim to the tract of country included within the following bounds, to wit:

“Beginning at the Arkansas River, at where the present Osage boundary line strikes the river at Frog Bayou; then up the Arkansas River and Verdigris to the falls of Verdigris River; thence eastwardly to the said Osage boundary line at a point 20 leagues north from the Arkansas River; and with that line to the place of beginning.”

In consideration of the above-described cession, the United States agreed to pay their citizens the losses they had sustained at the hands of the Osage, provided the same did not exceed the sum of $4,000.

Three years after this treaty was concluded, their agent at Fort Osage made the following report of their location and condition. The report was dated October 1, 1820:

“The Great Osage of the Osage River lived in one village on the Osage River, 78 miles due south of Fort Osage. They hunt over a very great extent of country, comprising the Osage, Gasconade, and Neosho Rivers and their numerous branches. They also hunt on the heads of the St. Francis and White Rivers, as well as on the Arkansas River. I rate them at about 1,200 souls, three hundred and fifty of whom are warriors and hunters, fifty or sixty superannuated, and the rest are women and children.

The Great Osage of the Neosho River lives about 130-140 miles southwest of Fort Osage in one village on the Neosho River. They hunt pretty much in common with the tribe of the Osage River, from which they separated six or eight years ago. This village contains about 400 people, of whom about 100 are warriors and hunters, some 10-15 aged persons, and the rest are women and children.

The Little Osage had three villages on the Neosho River about 120-140 miles southwest of this place. This tribe, comprising all three villages, and comprehending about 20 families of Missouri Indians that are intermarried with them are estimated at 1,000 people, about 300 of whom are hunters and warriors, 20-30 aged, and the rest are women and children. They hunt pretty much in common with the other tribes of the Osage frequently on the headwaters of the Kansas River, some of the branches of which interlock with those of the Neosho River.

Of the Chaneers, or Arkansa tribes of Osage, they do not come to the area to trade. They are equal in number to about half of all the other Osage. They hunt chiefly in the White Rivers.”

George C. Sibley.

George Sibley, the Indian agent, stated it was impossible to obtain an exact number of the tribes as they were continually moving from one village to another and intermarrying. As to their mode of subsistence, he wrote:

“The main dependence of each and every tribe is hunting. They also raise small crops of corn, beans, and pumpkins. These they cultivate entirely with the hoe in the most straightforward manner. Their crops are usually planted in April before they leave their villages for the summer hunt in May. About the first week in August, they returned to their villages to gather their crops, which had been left unhoed and unfenced all season.

Each family, if lucky, can save from ten to 20 bags of corn and beans, of a bushel and a half each, besides a quantity of dried pumpkins. On this, they feast, with the dried meat saved in summer, until September, when they set out on the fall hunt, from which they return about Christmas. From that time till some time in February or March, as the season happens to be mild or severe, they stay pretty much in their villages, making only short hunting excursions occasionally. In February or March, the spring hunt commences, which they pursue until planting time when they again return to their village.

This is the circle of an Osage life, here and there indented with war and trading expeditions, and thus, it has been with very little variation for years. The game is diminishing in the country that these tribes inhabit, but it has not yet become scarce. Its gradual diminution seems to have had no other effect on the Indians than to make them more expert and industrious hunters and better warriors.”

On June 2, 1825, the Osage Nation relinquished its title to all the lands it still claimed in Missouri and Arkansas, and in addition, ceded to the United States “all lands lying west of Missouri and Arkansas, north and west of the Red River, south of the Kansas River, and east of a line to be drawn from the head sources of the Kansas River southwardly through the Rock Saline.”

Article 2 of the treaty contained the following reservation:

“Within the limits of the country above ceded and relinquished, there shall be reserved to and for the Great and Little Osage tribes or nation aforesaid, so long as they may choose to occupy the same, the following described tract of land: “Beginning at a point due east of White Hair’s village and 25 miles west of the western boundary line of the State of Missouri, fronting on a north and south line, so as to leave ten miles north and forty miles south of the point of said beginning, and extending west, with the width of fifty miles, to the western boundary of the lands hereby ceded and relinquished by said tribes or nations.”

In addition to the principal reservation, various half-breed and other small reservations were located on the Neosho, Marais des Cygnes, and Mine Rivers, including the sections whereon the principal improvements had been made and those on which the missionary establishments were located.

The United States agreed to pay the Osage Nation, in consideration of the cession, yearly annuities to the amount of $7,000 for 20 years; also to provide for them stock, farming utensils, a person to teach them agriculture, and a blacksmith; to build for each of the four principal chiefs a comfortable and commodious dwelling-house, and to pay any debts which citizens of the United States, members of the Delaware nation, and certain traders, held against them.

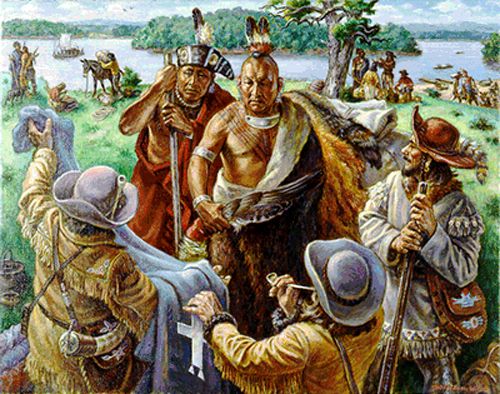

The trading interests among the Osage were principally in the hands of a few persons who represented large and influential companies at St. Louis. Pierre Choteau, Manuel De Lisa, Pierre Menard, Hugh Glen, and other early Indian traders acquired an ascendancy over this tribe and their affairs that proved detrimental, if not fatal, to the efforts of the Protestant missionaries and teachers who sought to induce them to forsake their wandering, savage life, and endeavor to procure a subsistence by the slow and unexciting methods of agriculture. Those of the traders who desired to enrich themselves by the barter in furs and peltries, of course, would desire to see the nation continue to follow the chase and would discourage any intimation of improvement.

Osage traders by Charles Banks Wilson, courtesy of the artist.

The impression was fostered that they were an uncommonly savage, warlike race, and the advent of educators among them was undesired and discouraged. This, added to their own indolence and apathy regarding improvement, disheartened those who made the earliest attempts at their advancement, and the early Protestant missions were abandoned.

In the course of ten or twelve years, the Osage were reduced in numbers and became a most degraded, servile people, neglected by the government and imposed upon by traders and agents. The teachers of agriculture stipulated in the treaty of 1825 were unable to render them much service and left the country. The blacksmiths also departed. Their annuities, after a few years, were paid to them in articles of but little real value, and, sinking from bad to worse, from poverty almost to starvation, they finally eked out the scanty supplies by incursions into the neighboring white settlements of Missouri. In 1837, these depredations became so serious that the frontier citizens of Missouri called for the assistance of the State militia, and a force of 500 men was sent to the border to quell the disturbances. The miserable condition of the Osage was reported to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in the fall of 1837. An act was passed on January 11, 1839, allowing them to take the amount of their next annuity in articles of food instead of money, making an appropriation to aid them in farming operations, and also providing them two millers and two blacksmith establishments.

In 1842, Fort Scott was established as a military post, and Hiero T. Wilson was appointed Post Sutler the succeeding year. This post became a trading resort for the Osage and continued as such for many years. The Catholic missionary institutions that were founded among them proved more successful than the early efforts of the Presbyterians, and many of the Osage children benefited from the various branches of the Catholic Osage Mission. White Hair, the venerable chief of the Grand Osage, became a convert to the faith, and after his death, his successor was also baptized into the communion of the same church. The Indian Agency was removed from the Neosho River to Quapaw country. Still, the Osage continued to live in their old villages, so a significant part of their time was spent hunting or idly wandering from place to place.

During the first year of the Civil War, the Osage Agency was moved to Fort Scott. One regiment of the Indian Brigade was composed of the Osage, and throughout the whole struggle, the tribe was faithful allies of the Unionists.

On September 19, 1865, by the terms of the treaty made at Canville Trading Post, the Great and Little Osage Indians sold to the United States the following defined country:

“Beginning at the southeast corner of their present reservation, and running thence north, with the eastern boundary thereof, fifty miles, to the northeast corner; thence west with the northern line, thirty miles; thence south fifty miles, to the southern boundary to said reservation; and thence east with said boundary to the place of beginning; provided that the western boundary of said land herein ceded shall not extend farther westward than a line commencing at a point on the southern boundary of said Osage country, one mile east of the place where the Verdigris River crosses the southern boundary of the State of Kansas.”

For this tract of country, afterward known as the “Osage Ceded Lands,” the United States was to pay $300,000, “which sum should be placed to the credit of the nation in the Treasury of the United States, interest at 5 percent thereon, to paid to the tribe semi-annually, in money or such articles or merchandise as the Secretary of Interior may direct,” no pre-emption claim or homestead settlement to be allowed on the land so ceded. After reimbursing the United States, the purchase money ($300,000), and paying the expense of survey and sale, the residue of proceeds to be placed in the United States Treasury to the credit of “Indian Civilization Fund.”

The Osage, by the same treaty, also ceded “a tract of land 20 miles in width from north to south off the north side of the remainder of their present reservation, and extending its entire length from east to west,” which land was to be held in trust for said Indians, and to be surveyed and sold for their benefit, under the direction of the Commissioner of the General Land Office, at a price not less than $1.25 per acre. This cession was known as the “Osage Trust Lands.”

The remaining strip, 30 miles in width and lying west of the “Ceded Lands,” was the “Osage Diminished Reserve.” After the treaty of 1865, the tribe moved on to this reservation, a part settling on Pumpkin Creek in the Verdigris Valley and several bands at the junction of Fall River with the Verdigris. On February 14, 1877, the Osage, after trying in vain to obtain the payments due from the United States under the terms of the treaty of 1865, made a contract with Charles Ewing, an attorney at Washington, by the terms of which, as approved by Honorable Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, Ewing was to obtain payment for all lands which had been sold or used contrary to the terms specified in the treaty; to procure certain payments for the Clermont band of Osage; to secure pensions to dependent families of Osage who were killed by Kansas militia in 1873, and patents for the lands owned by the Osage in the Indian Territory at the date of the contract. June 16, 1880, a law was enacted, directing, in effect, that the Osage should be paid an amount equivalent to the loss they had sustained by the non-observance of the treaty. They were accordingly credited with $1,028,785.15, paid in two settlements in August 1880 and June 1881.

When this contract was concluded in 1877, the tribe was divided into eight bands and numbered about 4,000 people. At Big Hill, the largest town, there were 100 lodges and about 950 people. White Hair’s band was reduced to between 300 and 400, and the Little Osage’s to 700. After the tribe obtained the payment of the sum due to them by the Government, their condition was materially altered for the better. By 1882, they numbered almost 2,000.

In 1907, the Osage, through the efforts of Principal Chief James Bigheart, negotiated to maintain mineral rights to their new reservation lands, which were later found to contain large amounts of crude oil. They were unyielding and held up statehood for Oklahoma before signing an Allotment Act.

Today, they are the only tribe since the early 20th Century to retain a federally recognized reservation within the state of Oklahoma. They have nearly 10,000 enrolled tribal members, with almost half of them living within the state of Oklahoma. The tribe is headquartered in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, and has jurisdiction in Osage County. They issue their vehicle tags, operate their housing authority, and own several businesses, including a truck stop, a gas station, 19 smoke shops, and seven casinos. The Osage Tribal Museum in Pawhuska is the oldest tribally-owned museum in the country.

More Information:

Osage Nation

P.O. Box 779

627 Grandview

Pawhuska, Oklahoma 74056

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated March 2025. About this article: The primary content for this article is an edited rendition of the Osage Indians as told in William G. Cutler’s History of the State of Kansas, first published in 1883 by A. T. Andreas, Chicago, Illinois. Note that the article is not verbatim, as minor corrections for spelling and punctuation, editing for clarity, and updates since the article was first written have been made.

Also See:

Native Americans – First Owners of America