Indian Home Guards.

During the Civil War, the First Indian Home Guard Regiment was organized in Kansas in May 1862. The tri-racial Union regiment comprised Creek and Seminole Indians, African-Creek, and African-Seminole, with white officers commanding the unit.

At the beginning of the war, Union troops abandoned their forts in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) to free up soldiers for campaigns further east, creating a vacuum that the Confederate Army rushed to fill. The absence of the Union Army made the Indians, particularly those known as the Five Civilized Tribes, which included the Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole, vulnerable to an alliance with the Confederacy. The fact that these tribes came from the South connected them culturally to the Confederacy. Some Indians, particularly the Cherokee, owned African American slaves.

The Chickasaw and the Choctaw readily embraced the Confederacy, but members of other tribes, such as the Creek and the Seminole, were divided. Many members of these tribes opposed a Confederate alliance and remained loyal to the Union.

As the Indian tribes chose sides, tensions mounted. Confederate Indians allied with Texas regiments came to battle against the Union loyalists, led by the Creek Chief, Opothle Yahola, in November-December 1861. Despite fierce resistance, Confederate troops prevailed and expelled the loyalists from the territory. This was the first of many battles that tore the Indian Territory into warring factions, with Indians splitting apart and fighting each other. The African Creek and African Seminole who joined the exodus were the first black men in America to raise arms against the Confederacy. The defeated Union loyalists fled to Kansas, leaving behind nearly everything in the way of food, clothing, and medicine, facing severe winter weather. The indescribable suffering of these Indians during the journey became known as the “Trail of Blood on Ice.”

Many froze to death as they trekked toward temporary, virtually shelterless camps along the Fall and Verdigris Rivers, where they stayed for a long winter. Relief for the Indian refugees was slow in coming as meager supplies of food and clothing trickled into the camps. However, it was not enough, and many died. Visitors to the camps described the conditions as wretched.

“It is impossible for me to depict the wretchedness of their condition. Their only protection from the snow upon which they lie is prairie grass and from the wind and weather scraps and rags stretched upon switches. Some of them had some personal clothing; most had, but shreds and rags that did not conceal their nakedness, and I saw seven varying in age from three to fifteen years without one thread upon their bodies… They greatly need medical assistance. Many have their toes frozen off; others have feet wounded by sharp ice or branches of trees lying on the snow. But few have shoes or moccasins. They suffer from inflammatory diseases of the chest, throat, and eyes. Those who come in last get sick as soon as they eat. Means should be taken at once to have the horses which lie dead in every direction through the camp and on the side of the river removed and burned, lest the first few warm days breed a pestilence amongst them.”

— A surgeon who visited the camps

When they crossed the border into Kansas, the refugees drew attention from government agencies in Kansas and the Union Army. Seeking to strengthen their position in Kansas and badly needing manpower, the commanders of the Union Army decided to recruit and train Indian soldiers from the ranks of these displaced tribes. Ultimately, the Army created three regiments of Native Americans known as the Indian Home Guards. Indians welcomed the opportunity to become soldiers, return, and defend their homes but faced challenges at every step. The Union Army, which aimed to reduce the risk of a Confederate invasion of Kansas, concurred with their desires and began planning an expedition to retake Indian Territory. Some Union commanders felt the Indians could provide the manpower needed for the expedition, so they began recruiting Indian soldiers and forming regiments. Many Kansans opposed their efforts, feeling that Indian soldiers would be inferior.

“Their principal use is to devour Uncle Sam’s hard bread and beef and spend his money. They will be as valuable as a flock of sheep in time of action. They ought to be disbanded immediately.”

— Fort Scott Bulletin

Others feared that Indians, once armed, would turn against the white population of Kansas. Some pointed to the reported behavior of Confederate Cherokee at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, who many believed to be responsible for scalping and mutilating Iowa troops.

Despite prejudice and misgivings, the recruitment of the Indians proceeded with the condition that they would only fight in Indian Territory (Oklahoma.) The Union Army formed two regiments – the First and Second Indian Home Guards.

The 1st and 2nd Regiment of Indian Home Guards were recruited by Brigadier General James Henry Lane in the winter of 1861 and 1862 and promised that if they joined the “Union” Army, they would be part of a campaign to return them to their homes from which they had been driven.

The First Regiment was organized at LeRoy, Kansas, on May 22, 1862, under Colonel Robert W. Furnas. It comprised 66 officers and 1,800 enlisted men composed mainly of Creek Indians and some Seminole and Blacks. The African Creek and African Seminole became the first blacks to be mustered into the Union Army. More men were organized on Big Creek and at Five-Mile Creek, Kansas, from June 22 to July 18, 1862.

The Second Regiment, under Colonel John Ritchie, was formed in southern Kansas and the Cherokee Nation between late June and early July 1862. It included 52 officers and 1,437 enlisted men.

The Third Regiment, under Colonel William A. Phillips, was formed at Tahlequah and Park Hill in July 1862. Its ranks were filled with Cherokee Pins, called so because of the cross pins worn on their coat lapels, and some former disaffected Confederate soldiers of Colonel John Drew’s First Cherokee Mounted Rifles.

The Indians’ first taste of war as Union soldiers came in the summer of 1862. The First and Second Indian Regiments accompanied several units of white soldiers in a quest to return the Indian refugees to their homes and to reestablish a Union presence in the Indian Territory.

Organized and supplied at Fort Scott, Kansas, the expedition’s soldiers experienced initial success. During the expedition, some became the first blacks to participate in combat. At the Battle of Prairie Grove, Arkansas, on December 7, 1862, they were the first black soldiers to participate in a significant battle. Though their numbers were few, the blacks in the unit played a key role in the regiment. Because most of the Indians did not speak English, the bilingual blacks served as interpreters and provided a cultural bridge between the white officers and the Indian soldiers.

When first organized, white officers had overall command of the regiments, but leadership of individual companies fell to the Indians. Not familiar with Army discipline or tactics, the Indian regiments did not immediately become effective fighting units. The Osage Indians of the Second Regiment never adjusted to Army regulations and procedures, and many were mustered out after a series of mass desertions.

Union victories near the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah resulted in defeating the Confederate troops and capturing several of their Cherokee allies. However, the expedition was short-lived, as Union commanders, fearing the disruption of supply lines, decided to withdraw.

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Downing served in the 3rd Indian Home Guard. He was later a chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Although only marginally successful, the expedition had one significant impact. Once freed from Confederate influence, many captured Cherokee joined the Union Army. Three Cherokee companies enlisted in the Second Indian Regiment, and enough recruits remained to form the Third Regiment of Indian Home Guards, organized in late August and early September 1862.

By the fall of 1862, the Army had replaced most of the Indian officers with white noncommissioned officers from other units to instill army discipline into the Indian regiments. All three regiments were organized to form the Indian Brigade. Increased drilling improved their performance, and in the spring of 1863, brigade commander William A. Phillips remarked that he was satisfied that all three regiments had become effective fighting units.

Fully trained, the Union Army and the Indian regiments returned to the Indian Territory more significantly. They fought in a series of pitched battles that would prove the resolve of the Home Guards.

In the battle at the site of old Fort Wayne in October 1862, the Third Indian Home Guard helped avert a flanking operation, pushing Confederate forces back seven miles and capturing their battle flag and four artillery pieces.

The seizure of Fort Davis, near present-day Muskogee, Oklahoma, in December 1862, was brought about by the actions of the Home Guards, who drove off the Confederate warriors stationed there and left the fort a smoldering ruins.

The Third Regiment remained to defend the Cherokee Nation after the Union Indian Expedition retreated from the area in late 1862.

During the capture of Fort Gibson in April 1863, the Second Indian Home Guard assisted in driving its Confederate defenders into the nearby Grand River, forcing the survivors to swim for their lives.

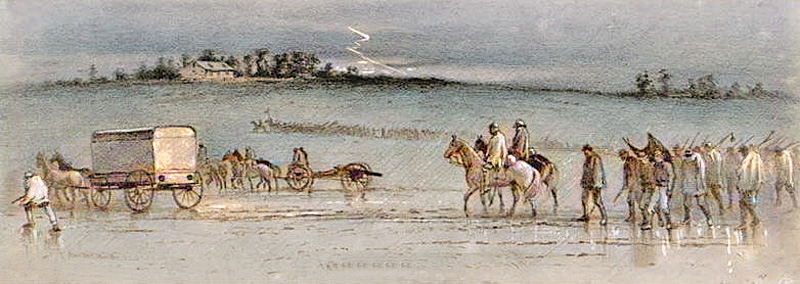

In July 1863, soldiers of the Indian Home Guards helped to save a Union supply train at Cabin Creek from being captured by the forces of Stand Watie, the most persistent of the Confederate Indian commanders.

The same month, at Honey Springs, the most crucial Confederate installation in Indian Territory, Indian regiments, along with white soldiers and African-American troops, combined in a pitched battle to drive the Confederates from the area, liberated valuable stores of supplies, secured the Union Army a firm foothold in Indian Territory.

The actions of the Union Home Guards enabled their families to begin returning home, some as early as the spring of 1863. But the war was not over; fierce and determined opposition brought about two more years of fighting.

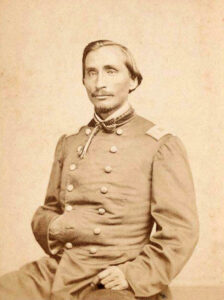

William Addison Phillips was a major of the First Indian Home Guard in Kansas.

In early 1864, the Indian Home Guards went on a march through the southern part of the territory, engaging in destruction and laying waste wherever they marched. Houses and other structures were destroyed, the economy ruined, and thousands became homeless refugees as tribes continued fighting each other. Tensions continued until the very end of the war.

The determination of the Indian Home Guards contributed to the ultimate Union victory. Individual soldiers felt a sense of pride with war whoops when they rode into battle. They had been driven from the Indian Territory in rags but came back in Union blue, victorious in their quest to return home.

The First Indians saw action on the battlefields of Missouri, Arkansas, and the Indian Territory and were mustered out in May 1865.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, January 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Black Past

Family Search

Fort Scott Tribune

National Park Service

National Park Service – 2

Oklahoma Historical Society