San Elizario, Texas Main Street, courtesy of Google Maps.

San Elizario is a city on the Rio Grande in El Paso County, Texas. At the 2020 census, its population was 10,116, and the city had a total area of 6.885 square miles, of which 0.0027 square miles was covered by water. It is part of the El Paso metropolitan statistical area. The city of Socorro adjoins it on the west, and the town of Clint lies to the north.

In 1598, Juan de Onate, a Spanish nobleman and conquistador from Mexico, led a group of 539 colonists and 7,000 head of livestock, including horses, oxen, and cattle, from southern Chihuahua to settle the province of New Mexico. The caravan traveled a northeasterly route across the desert for weeks until it reached the banks of the Rio Grande in the San Elizario area on April 30, 1598. A mass was held, with a blessing and a celebration. Onate performed the ceremony of La Toma (“Taking Possession”), in which he claimed the new province for King Philip II of Spain. This now historic trail connected Mexico City with Santa Fe, New Mexico, the then northern capital of New Spain. This is considered to be the “Birth of the American Southwest“.

The settlement that became San Elizario was first established sometime before 1760 as the Hacienda de los Tiburcios on the south side of the Rio Grande. The hacienda was located on the route of the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, now locally known as the Mission Trail. By 1765, the population had grown to 157.

The Presidio de San Slzeario, now called San Eliaario, was established as a fort or presidio in 1773. It was formally established on the present site of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, under the name of Presidio de Nuestra Señora del Pilar y de Glorioso SanJosé.

The hacienda system was abandoned in 1787.

By 1789, the area was on its way to becoming an established agricultural community when the Spanish military moved its military base, known as San Elceario, named for the patron saint of soldiers, from near present-day Fort Hancock to the site of Hacienda de los Tiburcios. The presidio kept its old name, and the settlement that grew up around it became known as San Elizario. The move was made to protect the new community from Apache attacks.

The self-contained garrison boasted 12-foot-high walls, a chapel, officers’ quarters, soldiers’ barracks, storerooms, and more—all of which were directly accessible via El Camino Real. The construction marked a shift in local building practices from the jacal technique, which involved sealing vertical logs with adobe plaster, to the widespread use of adobe bricks and vigas (ceiling beams), as well as more linear building plans. The Presidio’s massive walls provided a sense of security and permanence, forming a central nucleus and a point of orientation for a settlement that quickly grew inside and around it.

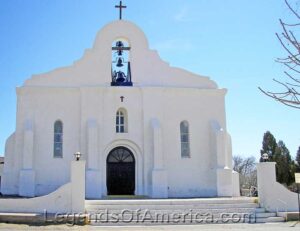

Its chapel, which still stands today, was never a mission, but it functioned as a presidio chapel. It provided the religious needs of a presidio or military outpost.

San Elzeario’s prominence as a point of trade began in the late 18th century, when a Chihuahua merchant won a contract as the presidio supplier, luring more trade caravans north along El Camino Real.

Merchant caravans passed through the town before the opening of the Santa Fe Trail, and Zebulon M. Pike and Peter Ellis Bean, a survivor of the Nolan expedition, were held there in 1807.

By the early 19th century, farmers, merchants, and other settlers had joined soldiers at San Elzeario. Among them were resident Apache Indians who participated in a military settlement program that offered security, food, and other provisions in exchange for peace.

The program drew hundreds of Apache to San Elzeario by 1814, when the military’s focus shifted to the Mexican War of Independence.

When Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821, the military presence at the presidio decreased. At that time, the rations and other protections for Apache residents were rescinded.

Mexican independence prompted the opening of the Santa Fe Trail from Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico, adding another vital connection to El Camino Real, then known as the Chihuahua Trail. San Elzeario’s commercial growth gave the community greater reason and resources to exist beyond the presidio’s original military purpose.

The Presidio’s military population declined over the next few decades as the Apache threat waned, but the community’s civilian population continued to grow.

A devastating flood in 1829 ravaged the community and placed San Elzeario on the Rio Grande’s north side.

Mexican troops still occupied the old presidio in 1835, and it served as the nucleus for a town with a population of 1,018 by 1841.

Members of the Doniphan Expedition occupied the presidio in February 1847.

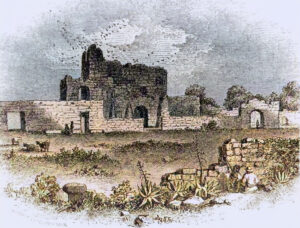

At the end of the Mexican-American War, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo determined “the deepest channel” of the Rio Grande as the boundary between Texas and Mexico. At that time, the town’s name was Americanized as San Elizario, and its residents became Texas residents. The town lay on the Lower El Paso or Military Road from Corpus Christi to California, and hundreds of Forty-Niners passed through the area in their rush for gold. Many visitors described the local peaches, plums, and wheat with admiration, and the wine produced from San Elizario grapes was highly regarded. By then, the presidio had fallen into ruins.

Companies of the Third Infantry under Jefferson Van Horne were stationed in the city from 1849 to 1852.

Americanization spurred a burst of activity as the Chihuahua Stage Line, Butterfield Overland Mail, and other coach and mail lines merged into El Camino Real. Enterprising Americans from the East flocked to town, making San Elizario the largest city in the lower El Paso valley and the county seat in 1850. A county courthouse and U.S. post office joined the San Bernal plaza and the presidio chapel of Nuestra Señora del Pilar y de Gloriosa (Our Lady of Pilar and Glorious St. Joseph) at the center of community affairs.

San Elizario was first established as a town in 1851, and a post office was opened.

After another flood in 1852, residents rebuilt on higher ground. Rebuilding efforts began in 1853 with the construction of a small church.

During the Civil War, troops of the California Column occupied the old presidio, but it was finally abandoned after the war.

San Elizario was incorporated for the first time in 1871.

Except for brief periods in 1854 and 1866, San Elizario remained the county seat until 1873, when its importance began to decline.

In 1877, a conflict known as the Salt War erupted between long-time Hispano residents and Anglo newcomers over rights to the salt deposits located just west of the Guadalupe Mountains, approximately 90 miles to the east. Nine people died in the Salt War, including a prominent Anglo merchant and an Anglo judge. Afterward, many residents of San Elizario fled across the Rio Grande to escape punishment, and the town lost much of its status.

In 1881, the railroad bypassed San Elizario in favor of El Paso. Afterward, merchants and other residents abandoned San Elizario in search of opportunities elsewhere. Railway exports led to a shift from sustainable to specialized agriculture, and San Elizario’s traditional farms struggled to keep up. The final snub came from the Southern Pacific Railroad, which bypassed San Elizario as a site for a lower valley train depot and built a brand new town, scarcely three miles away.

By 1882, the small church had become too small, and the present structure was completed. The exterior appearance has changed very little since then.

In 1883, El Paso became the county seat of El Paso County.

By the late 19th century, the old presidio was in a sorry state of disrepair, and residents salvaged its bricks to build new homes, stores, and other symbols of San Elizario’s prosperity.

In 1890, the estimated population was 1,500, and the town had two schools and a steam flour mill.

The town’s estimated population was 1,426 in 1904, but by 1914, it had declined to 834.

San Elizario was disincorporated in 1920.

The estimated population fell to 300 in 1931, but it climbed to 925 by the mid-1940s and 1,064 by the early 1960s.

In 1990, the population was 4,385. The population more than doubled, reaching 11,046 in 2000.

Some attempts to reincorporate in modern times were unsuccessful until March 2013, when a committee of San Elizario residents was formed to fight the City of Socorro’s annexation attempt. Through the committee’s hard work and the support of many in the region, the City of San Elizario was reborn on November 5, 2013.

The San Elizario Independent School District serves the community of San Elizario.

Once an action-packed crossroads of culture, commerce, and military affairs, San Elizario connects contemporary El Paso to the agricultural heartland of the lower El Paso Valley. This sleepy community, with a history spanning over 400 years, showcases its heritage in the adobe architecture of its frontier buildings.

Today, the Presidio Chapel remains an active parish in San Elizario, continuing to anchor the community. Four vertical bells and four horizontal buttresses bring an imposing symmetry to the relatively small building, which is set in a frame of low masonry walls and a dramatic sweep of front steps. Despite centuries of change, El Camino Real, today’s Glorieta Road, still leads residents and visitors to and from the chapel at the old presidio. It is located at 1556 San Elizario Road.

The plaza and chapel represent the location of the original presidio. The path of El Camino Real, which led into the presidio, is today’s Glorieta Road, and a network of historic acequias (irrigation ditches) further defines the district’s historic 27-acre core. It is the start of El Paso’s Mission Trail. The district features a diverse melding of residential, commercial, and civic buildings dating from the 1830s to World War II.

Among the most elegant Territorial-style examples is the mid-19th-century Casa Garcia, better known as the Los Portales Museum and Information Center, on the plaza’s south side. The home of Gregorio Garcia, a former El Paso County judge and Texas Ranger, was built in the 1850s. Defined by a long front portal with waves of cottonwood vigas across its impressive roof span. Previously used as a school, the building now hosts visitors from San Elizario and features exhibits highlighting the town’s history from the Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. periods. Walking tour brochures of the historic district are available for visitors.

Casa Ronquillo, also known as the Viceroy’s Palace, sits outside the village center adjacent to agricultural lands on the edge of the Acequia Madre (mother ditch). The former home of Josée Ignacio Ronquillo, a 19th-century mayor of San Elizario and the first presidio commander during the Mexican period, Casa Ronquillo was among the largest in town, featuring multiple entries, 12 rooms, three wings, and a large interior courtyard. After Ronquillo’s death, Charles Ellis, an Anglo merchant killed in the 1877 Salt War, purchased the home. It is situated southeast of the intersection of Alarcón Road and Convent Road, approximately 220 yards south of the village square.

Main Street highlights San Elizario’s commercial heyday, with buildings dating from the late-18th century to the mid-19th century presidio period. The buildings may contain adobe remnants of the old fortress.

Further down Main Street is the old 1850s jailhouse, whose exposed adobe brick walls and wood-plank door enclosed two steel-and-wrought-iron cage cells. Local legend has it that Billy the Kid assisted his friend, Melquiades Segura, in escaping from jail in 1876.

A private residence that once served as a rest station for the Butterfield Overland Mail Line still stands southeast of the presidio. While the home has been remodeled, it retains its rectangular shape, thick walls, and wide front gate, which is suitable for wagons.

San Elizario is at the intersection of Farm roads 258 and 1110, about 15 miles southeast of downtown El Paso in southern El Paso County.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Presidio de San Elizario, Texas

Sources:

City of San Elizario

National Park Service

Texas State Historical Association

Texas Time Travel