El Paso, Texas Skyline View by Carol Highsmith.

El Paso, Texas, Spanish for “the route” or “the pass,” is a city in and the county seat of El Paso County. At the far western tip of Texas, it stands on the Rio Grande across the Mexico–United States border from Ciudad Juarez, the most populous city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

The 2020 population from the U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the 22nd-most populous city in the country, the most populous city in West Texas, and the sixth-most populous city in the state. Its metropolitan statistical area covers all of El Paso and Hudspeth Counties, and it had a population of 868,859 in 2020.

The El Paso region, in the Chihuahuan Desert, has had human settlement for thousands of years, as evidenced by Folsom points from hunter-gatherers found at the nearby Hueco Tanks. This suggests 10,000 to 12,000 years of human habitation. The earliest known cultures in the region were maize farmers. When the Spanish arrived, the Manso, Suma, and Jumano tribes populated the area. These were subsequently incorporated into the mestizo culture (mixed ancestry), along with immigrants from central Mexico, captives from Comanchería, and genízaros of various ethnic groups. The Mescalero Apache were also present.

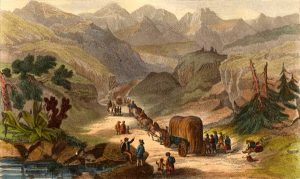

The city of El Paso has stood by the lowest natural pass in that region of deserts and mountains since the Spanish conquistadors first trudged through it nearly five centuries ago. As they approached the Rio Grande from the South, Spaniards in the 16th century viewed two mountain ranges rising out of the desert with a deep chasm between them. They named this site El Paso del Norte (the Pass of the North), which became the future location of two border cities—Ciudad Juarez on the south bank of the Rio Grande, and El Paso, Texas, on the opposite side of the river.

Since the 16th century, the pass has been a continental crossroads. During the Spanish and Mexican periods, a north-south route along a historic Camino Real prevailed. However, traffic shifted to an east-west axis in the years following 1848, when the Rio Grande became an international boundary.

Four survivors of the unsuccessful Narvaez expedition to Florida, Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Andres Dorantes de Carranza, and an enslaved native of Morocco, Estevanico, crossed the Rio Grande into present-day Mexico about 75 miles south of El Paso in 1535. While there, he visited Indian pueblos along the Rio Grande and wrote the earliest description of the people who lived here:

“They have the finest persons of any people we saw, of the greatest activity and strength, who best understood us and intelligently answered our inquiries. We called them the cow nation, because most of the cattle (buffalo) are killed and slaughtered in their neighborhood, and along that river for over 50 leagues, they destroy great numbers.”

Several years later, in 1540–42, an expedition under Francisco Vazquez de Coronado explored an enormous amount of territory now known as the American Southwest.

The first party of Spaniards that certainly saw the Pass of the North was the Chamuscado and Rodríguez Expedition, which trekked through present-day El Paso and forded the Rio Grande, and visited the Pueblo Indians in present-day New Mexico in 1581-1582. Its arrival marked the beginning of 400 years of history in the El Paso area.

This was followed by the Espejo-Beltran expedition of 1582 and the historic colonizing expedition under Juan de Onate, who, on April 30, 1598, in a ceremony at a site near that of present San Elizario, took formal possession of the entire territory drained by the Rio Grande, proclaiming the country the property of King Philip II of Spain.

This act, called La Toma, or “the claiming,” brought Spanish civilization to the Pass of the North and laid the foundations of more than two centuries of Spanish rule over a vast area.

El Paso del Norte (present-day Ciudad Juarez) was founded in 1659 by Fray Garcia de San Francisco on the south bank of the Rio Grande. He also founded he mission of Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe to convert the Manso, which still stands. Other mission settlements sprang up on both sides of the river.

The Pueblo Indian Revolt of 1680 turned the Pueblos of New Mexico against the Spanish colonists, who fled to the Rio Grande to take refuge at the pass.

El Paso del Norte became the seat of government for northern Mexico and a base of operations for the attempted reconquest of the Pueblos in 1681.

At that time, the small village of El Paso became the temporary base for Spanish governance of the territory of New Mexico. It remained there until 1692, when Santa Fe was reconquered and once again became the capital.

By 1682, five settlements had been founded in a chain along the south bank of the Rio Grande—El Paso del Norte, San Lorenzo, Senecu, Ysleta, and Socorro.

By the middle of the 1700s, about 5,000 people—Spaniards, mestizos, and Indians—lived in the El Paso area, the largest population complex on the Spanish northern frontier. A large dam and a series of acequias (irrigation ditches) made flourishing agriculture possible. The large number of vineyards that produced wine and brandy was said to have ranked as the best in the realm.

The Presidio of San Elizario was founded in 1789 to help defend the El Paso settlements against the Apache.

Zebulon M. Pike, a United States Army officer who was arrested and brought to El Paso in 1807 for trespassing on Spanish territory, described the irrigated fields and vineyards of the town and the valley. While there, writing:

“For hospitality, generosity, docility, and sobriety, the people of New Spain exceed any nation perhaps on the globe.”

With the establishment of Mexican independence from Spain in 1821, the El Paso area and what is now the American Southwest became a part of the Mexican nation. Agriculture, ranching, and commerce continued to flourish, but the Rio Grande frequently overflowed its banks, causing significant damage to fields, crops, and adobe structures.

It was not until 1827 that settlement was made in present-day El Paso, a community growing around Juan Maria Ponce de Leon’s ranch house.

In 1829, the unpredictable river flooded much of the lower Rio Grande Valley, forming a new channel that ran south of the towns of Ysleta, Socorro, and San Elizario. This placed them on an island some 20 miles in length and two to four miles in width. Of the various land grants made by the local officials in El Paso del Norte, the best known and most successful was given to Juan María Ponce De Leon, a Paseno aristocrat, in what is now the downtown business district of El Paso, Texas. By this time, a number of Americans were engaged in the Chihuahua trade, two of whom—James W. Magoffin and Hugh Stephenson—became El Paso pioneers at a later date.

El Paso del Norte knew little of the Texas Revolution in 1836, remaining a thoroughly Mexican town long after Texas became a republic. However, Texas claimed the region as part of the treaty signed with Mexico, and made numerous attempts to bolster these claims. Still, the villages that consisted of what is now El Paso and the surrounding area remained essentially self-governed with representatives of both the Mexican and Texan governments negotiating for control until Texas irrevocably took control in 1846.

In the meantime, prairie schooners were venturing across the Rocky Mountains to California and Oregon, and across the deserts to Santa Fe, New Mexico, before Anglo-Americans began trickling toward the mountain pass, attracted by trade with Chihuahua and Sonora.

Prisoners of the Santa Fe Expedition reached the Pass in the fall of 1841. The military commandant of El Paso was furious at the brutal treatment they had received and ordered them fed and clothed, declaring a three-day rest before they resumed the journey to Mexico City. Among the prisoners was George Wilkins Kendall, who wrote of his experiences in his Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition. He spoke well of El Paso’s citizens, described the commandant as “a well-bred, liberal and gentlemanly officer,” and said of the town:

“Almost the only place in Mexico I turned my back upon with anything like regret was the lovely town or city of El Paso.”

As early as the mid-1840s, alongside long extant Hispanic settlements such as the Rancho de Juan María Ponce de Leon, Anglo-American settlers such as Simeon Hart and Hugh Stephenson had established thriving communities of American settlers owing allegiance to Texas. Stephenson, who had married into the local Hispanic aristocracy, established the Rancho de San Jose de la Concordia, which became the nucleus of Anglo-American and Hispanic settlement within the limits of modern-day El Paso in 1844. The Republic of Texas, which claimed the area, wanted a chunk of the Santa Fe trade.

Colonel W.A. Doniphan descended from the mountains of New Mexico in 1846 with his regiment, bringing the isolated station the first taste of the Mexican–American War. The town of El Paso del Norte surrendered amiably. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 officially ended the Mexican War and fixed the boundary between the two nations at the Rio Grande, the Gila River, and the Colorado River.

It effectively made the settlements on the north bank of the river part of the United States, separate from Old El Paso del Norte on the Mexican side. All territory north of that line, known as the Mexican Cession and comprising half of Mexico’s national domain, became a part of the United States, which paid Mexico $15 million. Thus, El Paso del Norte, the future Ciudad Juarez, became a border town.

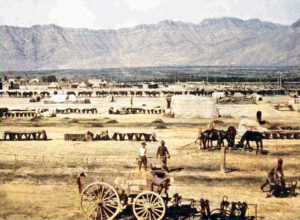

The California gold rush of 1849 brought a surge of west-bound traffic, and soon two important stage lines were sending their great leather-slung coaches through the Pass. Franklin was a crucial midway station when the Butterfield Stage Line opened the longest overland mail coach line in the world, connecting St. Louis, Missouri, with San Francisco, California.

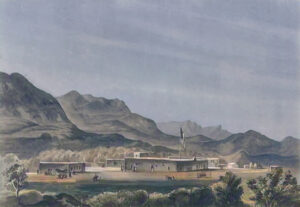

A military post called the “Post opposite El Paso” was established in 1849 on Coontz’s Rancho beside the settlement of Franklin, which later became Fort Bliss.

Early travelers were surprised to find the valley a prosperous and flourishing vineyard. Grapes of an Asiatic variety were said to have been introduced by the Franciscans. By the middle of the 19th century, a traveler referred to El Paso del Norte as “… a city of some size… many good homes, the vine extensively cultivated,” with a great trade in wine, raisins, and dried fruits. “Paso wine” and brandy were shipped into Chihuahua, up through New Mexico and east over the Santa Fe Trail, and for a time constituted the chief source of revenue.

El Paso County was established in March 1850, with San Elizario as the first county seat. The United States Senate fixed a boundary between Texas and New Mexico at the 32nd parallel, thus largely ignoring history and topography.

Simeon Hart, of Ulster County, New York, started a mill by the Rio Grande about 1850, establishing a community which became known as Hart’s.

The present New Mexico–Texas boundary, which places El Paso on the Texas side, was drawn in the September 1850 Compromise.

Benjamin F. Coontz, who had established a trading post near the two settlements, succeeded in obtaining a post office in 1852 for the town he founded and called Franklin.

Fort Bliss was established as a military post in 1854.

The El Paso Company, established in 1859, bought the area property. It hired Anson Mills to survey and lay out the town, thus forming the street plan of downtown El Paso.

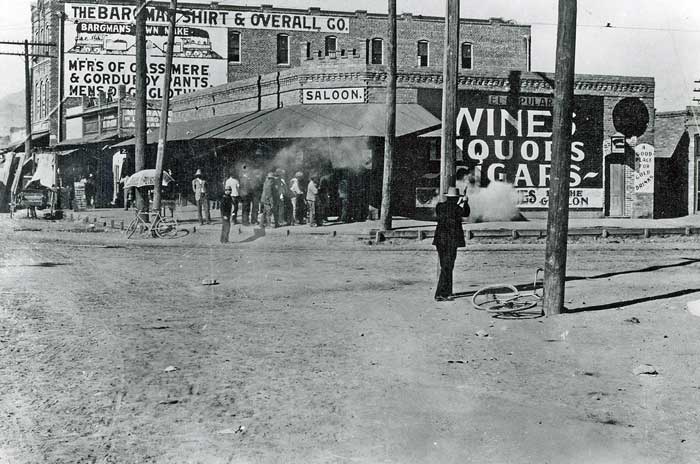

The use of Franklin’s name was officially discontinued after 1859. El Paso was still only a huddle of squat, one-story adobe houses wedged in between the mountain range and the river, without even a mission tower to break its flat skyline. The business district consisted of two stage stations with corrals, a hotel, a few stores, and enough saloons to satisfy everybody. The townspeople found leisure to watch for the incoming stages, played monMonteoker, and faro with the traders who rode into town on regular sprees, and bet on straightaway races and cock fights.

“The Texan town of El Paso had 400 inhabitants, chiefly Mexicans. Its businessmen were Americans, but Spanish was the prevailing language. All the features were Mexican: low, flat adobe buildings, shading cottonwoods under which dusky, smoking women and swarthy children sold fruit, vegetables, and bread; habitual gambling universal, from the boys’ game of pitching quartillas (three-cent coins) to the grand saloons where huge piles of silver dollars were staked at monMonten this little village, $100,000 often changed hands in a single night through the potent agencies of MonMonted poker. There were only two or three American ladies, and most of the whites kept Mexican mistresses. All goods were brought on wagons from the Gulf of Mexico and sold at an advance of 300% to 400% on Eastern prices.

From hills overlooking the town, the eye takes in a charming picture—a far-stretching valley, enriched with orchards, vineyards, and cornfields, through which the river traces a shining pathway. Across it appear the flat roofs and cathedral towers of the old Mexican El Paso; still further, dim, misty mountains melt into the blue sky.”

— Albert D. Richardson, traveling to California via coach, described El Paso as he found it in late 1859.

The Civil War came to El Paso with the surrender of the Federal garrison at Fort Bliss on March 31, 1861. At that time, most of the El Paso pioneers were overwhelmingly sympathetic to the South.

Texas troops occupied Fort Bliss on July 14, 1861, and on July 23, Colonel John Baylor moved north up the valley against the Federals in New Mexico. By August, he had accomplished his mission and returned to the El Paso region to establish headquarters at Mesilla. Brigadier General H.H. Sibley reinforced Baylor in December of 1861 and took over command of the column, which was designated as the Army of New Mexico. After an ineffectual campaign to conquer New Mexico, he withdrew to San Antonio, Texas, in about the middle of July, 1862. The Union California Column captured it and occupied Fort Bliss on August 18, 1862. From August 1863 until December 1864, it was the headquarters for the 5th Regiment, California Volunteer Infantry. The Middle Valley of the Rio Grande remained in undisputed control of the Federals until the close of the war.

After the war, El Paso’s population began to grow as white Texans continued to move into the villages and soon became the majority.

El Paso was incorporated in 1873 when the population consisted of 23 Anglo-Americans and 150 Mexicans. Benjamin S. Dowell, who ran a saloon, was its first mayor. “Don Benito,” as he was called, found his hands full when he attempted to make the settlement a city. The first city ordinance made it “… a misdemeanor for any person to bathe in any acequias in this city… or to drive any herds of sheep… or other animals into any acequia…”

At that time, the Apache were making their final raids while prospectors swarmed down from the Rocky Mountains, along with numerous desperadoes and gunmen who found the river a convenient crossing at this point. This all combined to keep the infant city in a state of turmoil.

The habits of the Rio Grande added to the confusion. This waterway, often referred to as “a mile wide and a foot deep, too thin to plow and too thick to drink,” was forever changing its course. One might be living in El Paso one day and in El Paso del Norte the next, and the lawless of the two nations evaded pursuit by simply wading into another country.

At that time, Indians, Spaniards, and Mexicans obtained water by digging ditches into their fields and homes from the river. Water from shallow wells was unpalatable, and those who could afford it bought drinking water from firms that obtained it in Deming, New Mexico. Efforts to pipe water from the Rio Grande failed because silt clogged the mains.

In 1877, El Paso felt the specific effects of the Salt War, which centered near San Elizario. This bloody racial conflict had little to do with salt, but it set Texans against Mexicans, and the United States against Mexico. Bad blood, personality conflicts, and intense personal rivalries characterized the affair, and mob violence, rape, robbery, and murder went unpunished with the breakdown of law enforcement. At length, Fort Bliss, which had been shut down, was reestablished, and six months of bloodshed were brought to a halt.

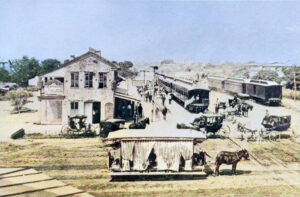

The arrival of the Southern Pacific, Texas and Pacific, and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroads in 1881 transformed the sleepy, dusty little adobe village of several hundred inhabitants into a flourishing frontier community.

El Paso became the county seat in 1883.

Public education in El Paso began with the establishment of an elementary school in 1884 and a high school in 1885.

By 1890, the city had a population of more than 10,000, including many Anglo-Americans, recent immigrants, old Hispanic settlers, and recent arrivals from Mexico. Along with the railroad builders and their labor gangs came a rush of Wild West desperadoes, gunmen, and gamblers. Within no time, scores of saloons, dance halls, gambling halls, and houses of prostitution lined the main streets. El Paso’s location and the arrival of these more wild newcomers caused the city to become a violent and wild boomtown known as the “Six-shooter Capital” and “Sin City,” because of its lawlessness.

At first, the city fathers exploited the town’s evil reputation by permitting vice for a price. However, in time, the more farsighted began to insist that El Paso’s future might be in jeopardy if vice and crime were not brought under a measure of control. In the 1890s, reform-minded citizens conducted a campaign to curb El Paso’s most visible forms of vice and lawlessness.

Among gunmen who made their headquarters in the city was John Wesley Hardin, who reputedly killed 27 men.

The Kansas City Smelting and Refining Company constructed a large smelter at El Paso in 1887. In 1899, it merged with several smaller companies to become the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO), which continued to be a major local employer into the 1980s.

The town across the river, El Paso del Norte, was renamed Ciudad Juarez in 1888.

The El Paso and Northeastern Railway was chartered in 1897 to help extract the natural resources of surrounding areas, especially in southeastern New Mexico Territory. Order was reestablished in the city through the efforts of a succession of straight-shooting sheriffs, city marshals, and Texas Rangers.

After 1900, El Paso began to shed its frontier image and develop as a modern municipality and significant industrial, commercial, and transportation center.

In 1905, El Paso voted out gambling houses, dance halls, and prostitution and applauded the informal justice meted out to its undesirables.

A photographer captures a five-minute gunfight at the corner of Seventh & El Paso St, in El Paso, TX, late 1907. (Photo credited to El Paso Public Library, Southwest Collection)

In 1909, the El Paso Chamber of Commerce hosted U.S. President William Howard Taft and Mexican President Porfirio Díaz at a planned summit in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, a historic first meeting between the Presidents of the two countries, and also the first time an American President crossed the border into Mexico. However, tensions rose on both sides of the border, including threats of assassination; so the Texas Rangers, 4,000 U.S. and Mexican troops, U.S. Secret Service agents, FBI agents, and U.S. Marshals were all called in to provide security.

The city grew from 15,906 in 1900 to 39,279 in 1910. By that time, the majority of the city’s residents were Americans, creating a settled environment. Still, this period was short-lived, as the Mexican Revolution greatly impacted the city, bringing an influx of refugees and capital to the bustling boom town. Spanish-language newspapers, theaters, movie houses, and schools were established, many supported by a thriving Mexican refugee middle class.

The Texas School of Mines and Metallurgy opened in 1914 and held its first commencement in 1916.

In 1916, the Census Bureau reported El Paso’s population as 53% Mexican and 44% non-Hispanic whites. Mining and other industries gradually developed in the area.

By that time, various Mexican revolutionary societies planned, staged, and launched violent attacks against both Texans and their political Mexican opponents in El Paso. This state of affairs eventually led to the vast Plan de San Diego, which resulted in the murder of 21 American citizens. The subsequent reprisals by a local militia soon caused an escalation of violence, wherein an estimated 300 Mexicans and Mexican-Americans lost their lives. These actions affected almost every resident of the entire Rio Grande Valley, resulting in millions of dollars in losses; the result of the Plan of San Diego was long-standing enmity between the two ethnic groups.

Prostitution and gambling flourished until the United States entered World War I in 1917, when the Department of the Army pressured El Paso authorities to crack down on vice, which obviously benefited vice in neighboring Ciudad Juarez. With the suppression of the vice trade and in consideration of the city’s geographic position, the city continued to develop as a premier manufacturing, transportation, and retail center of the U.S. Southwest.

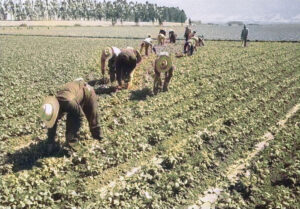

In 1917, it was discovered that both El Paso and Juarez were lying above an underground lake, and several deep wells provided an abundance of water. Elephant Butte Dam, 120 miles north in New Mexico, furnished irrigation for 74,600 acres in El Paso and Hudspeth Counties, which would otherwise have remained a desert. Irrigated fields yielded sugar beets for seed purposes, tomatoes, chili peppers, beans for local canning plants, and onions for an extensive market. Pear orchards furnished a profitable yield. An outstanding grade of long-staple, strong fiber cotton was also raised.

At that time, Mexican craftsmen wove rugs, blankets, and sarapes on old-fashioned hand looms in their shops along Third Street, and modern factories in the neighborhood of South Stanton and Second Streets made tortillas. Pottery makers worked in the southern and eastern parts of the city, especially in the vicinity of Washington Park. Another industry was the manufacture of hand-tooled leather goods and furniture.

By 1920, along with the U.S. Army troops, the population exceeded 100,000, and non-Hispanic Whites once again were in the clear majority. Nonetheless, the city increased the segregation between Mexicans and Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic Whites.

Prohibition Poster.

That year, Prohibition began, awakening the city to its possibilities as a tourist resort. Thousands flocked in to cross the river to Juarez, visiting the drinking and gambling establishments, and El Paso thrived.

Standard Oil Company of Texas (now Chevron USA), Texaco, and Phelps Dodge located major refineries in El Paso in 1928 and 1929.

During this time, El Paso saw the emergence of significant business development, partially enabled by Prohibition-era bootlegging. The military demobilization and agricultural economic depression, though, hit places like El Paso first before the larger Great Depression was felt in the big cities.

As a result, El Paso’s population declined through the end of World War II. Most of the population losses came from the non-Hispanic White community, which remained the majority until the 1940s.

By 1940, El Paso held a strategic position as a port of entry, being the largest city on the Texas-Mexico border, and across the river from the largest city in northern Mexico. Crude ores were shipped to their smelter from mines in northern Mexico, New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona, and quantities of refined ores were exported. At that time, the city had two canning plants, two copper refineries, and several oil refineries. The city was also the headquarters for the El Paso Customs District, which included New Mexico and Texas, west of the Pecos River.

During and following World War II, military expansion in the area, as well as oil discoveries in the Permian Basin, helped to engender rapid economic expansion in the mid-1900s. Copper smelting, oil refining, and the proliferation of low-wage industries (particularly garment making) led to the city’s growth. Additionally, the departure of the region’s rural population, which was mainly non-Hispanic White, to cities like El Paso brought a short-term burst of capital and labor, but this was balanced by additional departures of middle-class Americans to other parts of the country that offered new and better-paying jobs. In turn, local businesses looked south to the opportunities afforded by cheap Mexican labor.

From 1942 to 1956, the Mexican Farm Labor Program brought cheap Mexican labor into rural areas to replace the losses of the non-Hispanic White population. In turn, seeking better-paying jobs, these migrants also moved to El Paso. Fort Bliss was responsible for much of El Paso’s growth during the 1940s and 1950s, when El Paso absorbed the town of Isleta and significantly increased its municipal area.

The State School of Mines and Metallurgy changed its name to Texas Western College in 1949.

Meanwhile, the postwar expansion slowed again in the 1960s. However, the city continued to grow with the annexation of surrounding neighborhoods.

By 1965, Hispanics once again were a majority.

Texas Western College became the University of Texas at El Paso in 1967.

The Farah Strike occurred in El Paso, Texas, from 1972 to 1974. This strike was initiated and led by Chicanas, or Mexican-American women, against the Farah Manufacturing Company due to complaints about the company’s inadequate compensation of workers. Texas Monthly described the Farah Strike as the “strike of the century.”

Textiles, tourism, the manufacture of cement and building materials, the refining of metals and petroleum, and food processing were El Paso’s major industries in 1980. Wholesale and retail tradespeople accounted for 23.3% of the local workforce, professionals 20.8%, and government employees 20.9%. Prominent local brands included Tony Lama boots and Farah slacks.

In 1983, El Paso-Juarez was the largest binational urban area along the Mexican-American border.

In 1986, military personnel made up one-fourth of the city’s population and accounted for one out of every five dollars flowing through El Paso’s economy.

On August 3, 2019, a terrorist shooter espousing white supremacy killed 23 people at a Walmart and injured 22 others.

El Paso lies directly under the crumbling face of Comanche Peak, spreading out fan-shaped around the foot of the mountain. Fashionable residences, primarily of modified Spanish or Pueblo architecture, lie near the mountain, their roofs bright against gray rocks. The city’s international tone is evident everywhere, on the streets, which bear English and Spanish names and where fluent Spanish is spoken by Texans as well as Mexicans.

El Paso has a diversified economy focused primarily on international trade, military, government civil service, oil and gas, health care, tourism, and service sectors. Cotton, fruit, vegetables, and livestock are also produced in the area. El Paso has added a significant manufacturing sector with items and goods produced that include petroleum, metals, medical devices, plastics, machinery, defense-related goods, and automotive parts.

The city also has a significant military presence with Fort Bliss, William Beaumont Army Medical Center, and Biggs Army Airfield. The defense industry in El Paso employs over 41,000 people and has a $6 billion annual impact on the city’s economy.

In addition to the military, the federal government has a strong presence in El Paso to manage its status and unique issues as an important border region. Operations headquartered in El Paso include the DEA Domestic Field Division 7, El Paso Intelligence Center, Joint Task Force North, U.S. Border Patrol El Paso Sector, and U.S. Border Patrol Special Operations Group.

Education is also a driving force in El Paso’s economy. El Paso’s three large school districts are among the largest employers in the area.

El Paso has won the All-America City Award five times: 1969, 2010, 2018, 2020, and 2021.

Today, the city’s oldest and most historic neighborhoods are located in the heart of the city. Downtown El Paso, with its winding streets and restored adobe buildings housing restaurants and shops, is popular with visitors. The city’s attractions include the El Paso Museum of Art and the El Paso Museum of History. Other historic districts in this area include the Rio Grade Avenue Historic District, the Segundo Barrio Historic District, and the Magoffin Historic District. It is close to the El Paso International Airport, the international border, and Fort Bliss.

On the U.S. side, the El Paso metropolitan area forms part of the larger El Paso–Las Cruces combined statistical area, which includes Las Cruces, New Mexico, with a population of 1,098,541. These three cities form a combined international metropolitan area sometimes referred to as the Paso del Norte or the Borderplex. The region of 2.7 million people constitutes the largest bilingual and binational workforce in the Western Hemisphere.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2025.

Also See:

El Paso Salt War

Spanish Missions in Texas

Texas – The Lone Star State

Texas Photo Galleries

Sources:

Encyclopedia Britannica

Federal Writers’ Program; Texas: A Guide to the Lone Star State, Works Projects Administration, 1940.

Texas State Historical Association

Wikipedia