Tropical paradise by day and urban playground by night, Miami, Florida, is a coastal city and the county seat of Miami-Dade County. Located in the southern part of the state, it is the core of the Miami metropolitan area, which, with a population of 6.14 million, is the second-largest metropolitan area in the Southeast after Atlanta, Georgia. As of the 2020 census, its population was 442,241, making it the second-most populous city in Florida after Jacksonville. Miami has the third-largest skyline in the U.S., with over 300 high-rises, of which 61 exceed 491 feet. It was named after the Miami River, derived from Mayaimi, the historic name of Lake Okeechobee, and the Native Americans who lived around it until the 17th or 18th century.

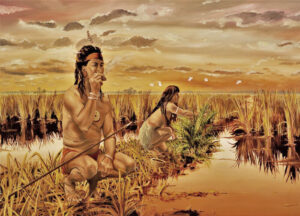

The Tequesta tribe occupied the area for about 2,000 years before contact with Europeans. At the mouth of the Miami River, a village of hundreds of people, dating to 500-600 BC, was located.

The Tequesta Indians were of the Calusa nation. Cruel, shrewd, and mercenary, they practiced human sacrifice of captives, scalped and dismembered their slain enemies, and were repeatedly accused of being cannibals. They murdered most of the priests, explorers, and adventurers who came among them or who were so unfortunate as to be shipwrecked on their coast.

At the time of first European contact, they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. The Tequesta Indians fished, hunted, and gathered fruits and roots of plants for food but did not practice any form of agriculture. The Tequesta are credited with making the Miami Circle. They had infrequent contact with Europeans and had migrated mainly by the middle of the 18th century.

In 1513, Juan Ponce de Leon was the first European to visit the Miami area by sailing into Biscayne Bay. It is unknown whether or not he came ashore or made contact with the natives.

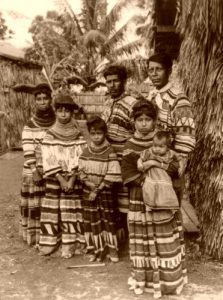

When white men began exploring and colonizing Florida, the state was occupied by several Indian tribes that were somewhat closely related but spoke different dialects. Though living in villages, they were somewhat nomadic due to occasional floods or seasonal journeys for food. Their diet mainly consisted of fish and game supplemented by fruits and vegetables. As a “canoe” people, most of their villages were located near bodies of water, as evidenced by the many mounds along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts and the streams and lakes in the state’s interior.

Studies of these mounds revealed that the peninsula was divided into two archeological areas. Tribes of Timucuan stock held that part lying north of Lake Okeechobee, while the Calusa dominated the southern end of the state, part of the east coast, and the Florida Keys.

Escalante de Fontanedo, the only survivor of a Spanish vessel wrecked on the Florida Keys in 1545, was the first white man to spend any time in South Florida. During the 17 years of his captivity among the Calusa Indians, he was permitted to explore the peninsula and visit the camps of various tribes.

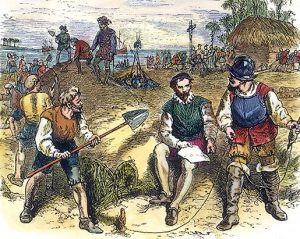

Captain Pedro Menendez de Aviles, a Spanish sailor, soldier, explorer, and conquistador, and his men made the first recorded landing in this area when they visited the Tequesta settlement in 1566 while looking for Menendez’s missing son, who had been shipwrecked a year earlier. Claiming the area for Spain, Menendez became Florida’s first governor. Spanish soldiers, led by Father Francisco Villareal, built a Jesuit mission of a blockhouse that sheltered about 30 soldiers. Villareal also instructed the Indians in the Christian faith. The mission of the Tequesta included a small garrison, but it was short-lived. The mission and garrison were withdrawn a couple of years later.

By 1570, the Jesuits sought more willing subjects outside of Florida. After the Spaniards left, the Tequesta Indians remained to fight European-introduced diseases, such as smallpox. Without European help, wars with other tribes significantly weakened their population, and the Creek Indians easily defeated them in later battles.

By 1711, the Tequesta had sent a couple of local chiefs to Havana to ask if they could migrate there. The Spanish sent two ships to help them, but illnesses struck, killing most of their population.

In 1743, the governor of Cuba sent Spaniards to Biscayne Bay to establish another mission. After building a fort and a church, the missionary priests proposed a permanent settlement where the Spanish settlers would raise food for the soldiers and Native Americans. However, the proposal was rejected as impractical, and the mission was withdrawn before the end of the year.

In 1748, Spain and England concluded a treaty to keep peace between their respective colonies in the New World. However, Spain joined France in the French and Indian War in 1759. Three years later, Havana and Cuba fell into English arms. Spain regarded Cuba with more interest than Florida and, therefore, succeeded in trading the English out of their possession when peace was made, offering them the Territory of Florida. Thus, under the Treaty of Paris in 1763, Florida passed to the English, having been under Spanish rule for nearly two centuries.

In 1766, Samuel Touchett received a land grant from the Crown for 20,000 acres in the Miami area. A condition for making the grant permanent was that at least one settler had to live on the grant for every 100 acres of land. While Touchett wanted to found a plantation in the grant, he had financial problems, and his plans never came to fruition.

In 1774, Governor Patrick Tonyn was in charge of the government of East Florida. King George III divided his prize into East and West Florida in 1763, when the last Calusa were transported from Dade County to Cuba. Tonyn’s name is of interest because it is said to be affixed to the first land grant in this area.

After the American Revolution, Florida remained an English possession but was later traded back to Spain, with England receiving the Bahamas in return. During the English regime, many loyal subjects of the King and others were led to settle in Florida. Most of them might have retained their holdings, but to do so, they would have to swear allegiance to the Spanish King. The English Crown generously offered to reimburse subjects who held Florida lands and preferred to lose them rather than become subjects of Spain.

The first permanent European settlers in the Miami area arrived in about 1800. Pedro Fornells, a Menorcan survivor of the New Smyrna colony, moved to Key Biscayne to meet the terms of his Royal Grant for the island. Although he returned with his family to St. Augustine after six months, he left a caretaker on the island. On a trip to the island in 1803, Fornells noted the presence of squatters on the mainland across Biscayne Bay from the island.

In 1810, American settlers in West Florida rebelled, declaring independence from Spain. President James Madison and Congress used the incident to claim the region, knowing that Napoleon’s invasion of Spain weakened the Spanish government. He soon sent Governor Claiborne of New Orleans, Louisiana, to take possession of West Florida.

The United States asserted that the portion of West Florida from the Mississippi River to the Perdido Rivers was part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Negotiations over Florida began in earnest with the mission of Don Luis de Onís to Washington, D.C., in 1815 to meet Secretary of State James Monroe. Along the Gulf of Mexico, the strip of land called West Florida became the refuge of pirates, outlaws, runaway slaves, and Indians. Marauding bands hampered the development of the adjoining territory, and lawless men preyed on shipping from Gulf ports.

The issue was not resolved until James Monroe was president. It became critical when General Andrew Jackson seized the Spanish forts at Pensacola and St. Marks in his 1818 authorized raid against Seminole Indians and escaped slaves who were viewed as a threat to Georgia. The United States used Jackson’s military action to present Spain with a demand to either control the inhabitants of East Florida or cede it to the United States.

In 1821, after controlling the Miami area for nearly 250 years, Spain sold Florida to the United States for the equivalent of $5 million.

In 1825, U.S. Marshal Waters Smith visited the Cape Florida Settlement on the mainland and conferred with Bahamian squatters who wanted to obtain title to the land they were occupying. They had settled along the coast beginning in the 1790s. John Egan had also received a grant from Spain during the Second Spanish Period. John’s son James Egan, his wife Rebecca Egan, his widow Mary “Polly” Lewis, and Mary’s brother-in-law Jonathan Lewis all received 640-acre land grants from the U.S. in present-day Miami. Though Temple Pent and his family did not receive a land grant, they stayed in the area.

In 1825, the Cape Florida Lighthouse was built on nearby Key Biscayne to warn passing ships of the dangerous reefs.

In 1830, Richard R. Fitzpatrick of Columbia, South Carolina, bought land on the Miami River from Bahamian James Egan. Fitzpatrick was a man of industry and resources, brought many slaves, and began an ambitious agricultural program, clearing the jungle growth along the shore three miles south of the Miami River and one mile north of it. Utilizing slave labor, he established a plantation of cotton, sugarcane, bananas, maize, and tropical fruit.

The increasing intrusion of white men into territory held by the Indians brought on the same difficulties in Florida. At that time, Major William S. Harney led several attacks on the Indians. The Seminole, increasingly furious at attempts by the U.S. Army to forcefully relocate them to a reservation in Oklahoma, ambushed two U.S. companies of 110 men under Major Francis Langhorne Dade, leading a supply train from Fort Brooke to Fort King was ambushed by approximately 180 Seminole and Black Seminole warriors on December 23, 1835. Only three U.S. soldiers and their guide, Louis Pacheco, survived the attack, and one died of his wounds the following day. The battle sparked the Second Seminole War. The troops began scouting the Everglades to locate and destroy Indian camps, depots, and supply trails.

Fort Dallas was first established as a naval post in 1834 when Lieutenant L.M. Powell of the United States Navy landed at the mouth of the Miami River and built a stockade. For two years, the patrol of Biscayne Bay and the scouting of adjacent territory were maintained.

In January 1836, shortly after the beginning of the Second Seminole War, Richard Fitzpatrick grew alarmed, removed his slaves, and closed his plantation to Key West. There, he also became a collector of customs.

Dade County was created on February 4, 1836, under the Territorial Act of the United States. The county was named after Major Francis L. Dade, a soldier killed in 1835 in the Second Seminole War. In the following years, the Dade County county seat was held at various sites, including Indian Key, Key West, Brickell Point, Cape Florida, Fort Dallas, Juno, and Miami.

That year, the United States Army took over Fort Dallas as a military base on the north banks of the Miami River on Fitzpatrick’s plantation as part of their development of the Florida Territory and attempted to suppress and remove the Seminole. As a result, the Miami area became a site of fighting. The Seminole War was the most devastating Indian war in American history, causing almost a total loss of native population in the Miami area. The Cape Florida lighthouse was burned by Seminole in 1836 and was not repaired until 1846.

After the Second Seminole War ended in 1842, Fitzpatrick’s nephew, William English, re-established the plantation in Miami. He chartered the “Village of Miami” on the south bank of the Miami River and sold several plots of land.

Miami became the county seat in 1844, and in 1850, a census reported that 96 residents lived in the area.

By 1850, the English plantations were deserted. After 1858, the soldiers withdrew, and the old buildings became the headquarters for blackguards and outlaws and so remained for nearly 20 years.

When William English died in California in 1852, his plantation died with him.

The Third Seminole War began in 1855 and lasted until 1858. It was not nearly as destructive as the previous one, but it slowed the settlement rate in southeast Florida. At the war’s end, a few soldiers remained, and some Seminole remained in the Everglades.

From 1858 to 1896, only a few families made their homes in the Miami area, living in small settlements along Biscayne Bay. The first of these settlements formed at the mouth of the Miami River and was variously called Miami, Miamuh, and Fort Dallas. Foremost among the Miami River settlers were the William Brickell family. William Brickell had previously lived in Cleveland, Ohio, California, and Australia. In 1870, Brickell bought land on the south bank of the river, where the family operated an Indian trading post and post office for the rest of the 19th century. When he became interested in public affairs, the governor appointed him a county commissioner. He also began buying land south of the river from Harriet English, who had inherited the holdings of her brother, Richard Fitzpatrick.

About the time of Brickell’s arrival, a settlement was underway at Coconut Grove. A store was built there in 1870, and a post office was established in 1873.

In the early 1880s, Ralph Middleton Munroe and others in Coconut Grove established a factory for canning pineapples, fish, and jellies. However, the venture did not succeed due to a lack of transportation facilities.

In 1891, Julia Tuttle, a wealthy Cleveland, Ohio native, moved to South Florida to make a new start in her life after the death of her husband, Frederick Tuttle. She purchased 640 acres on the north bank of the Miami River in present-day downtown Miami and became a local citrus grower. Tuttle was no stranger to the area. She was the daughter of Ephraim T. Sturtevant, who came to Dade County about 1871. She visited her father in Dade County in 1880 and made a second visit two years later. With the Brickells on the river’s south bank, the stage was set for the future Miami.

She soon tried to persuade railroad magnate Henry Flagler to expand his Florida East Coast Railway southward to the area, offering half her holdings to Flagler as an inducement to build. Flagler initially declined.

In December 1894, a freeze destroyed the citrus crop in North Florida. A few months later, on February 7, 1895, the northern part of Florida was hit by another freeze that wiped out the remaining crops and new trees. Thousands of grove owners were broke, and many thought it spelled the end of the industry. The crops of the Miami area were the only ones in Florida that survived.

Afterward, Tuttle wrote to Flagler again, asking him to visit and see the area himself. Flagler sent James E. Ingraham to investigate, and he returned with a favorable report and a box of orange blossoms to show that the area had escaped the frost. Flagler followed up with a visit and, by the end of his first day, concluded that the area was ripe for expansion. He then extended his railroad to Miami and built a resort hotel.

On April 22, 1895, Flagler wrote a letter to Tuttle recapping her land offer to him in exchange for extending his railroad to Miami, laying out a city, and building a hotel. The terms provided that Tuttle would award Flagler a 100-acre tract of land for the city to grow. Around the same time, Flagler wrote a similar letter to William and Mary Brickell, who had also verbally agreed to give land during his visit.

While the railroad’s extension to Miami remained unannounced in the spring of 1895, rumors of this possibility spread, fueling real estate activity in the Biscayne Bay area. The news of the railroad’s extension was officially announced on June 21, 1895. In late September, the work on the railroad began, and settlers began pouring into the promised “freeze-proof” lands. On October 24, 1895, the contract agreed upon by Flagler and Tuttle was approved. The census of 1895 gave Dade County a population of 3,322, most of which was in the northern part.

Miami is noted as the only major city in the United States founded by a woman. Julia Tuttle became known as “the mother of Miami.”

With the railroad under construction, activity in Miami began to pick up. Men from around the state, many of whom were victims of the freeze, flocked to Miami to await Flagler’s call for workers on the promised hotel and city. By late December 1895, 75 were already at work clearing the site for the hotel. They mainly lived in tents and huts in the wilderness, with no streets and few cleared paths.

On February 1, 1896, Tuttle fulfilled the first part of her agreement by signing two deeds to transfer land for Flagler’s hotel and the 100 acres near the hotel. On March 3, Flagler hired John Sewell from West Palm Beach to begin work on the town as more people entered Miami. On April 7, 1896, the railroad tracks reached Miami, and the first train arrived on April 13 with Henry Flagler on board. The train returned to St. Augustine later that night. The first regularly scheduled train arrived on April 15. The first week of train service was provided only for freight trains; passenger service did not begin until April 22. There was no station, only a platform with a shack for a telegraph office at one end.

Initially, most residents wanted to name the city “Flagler.” However, Henry Flagler did not want it named after him. On July 28, 1896, the City of Miami, named after the Miami River, was incorporated with 502 voters, including 100 registered black voters. John B. Reilly, who headed Flagler’s Fort Dallas land company, was the first eleMayormayor.

Miami Avenue was the first thoroughfare to be cut. Flagler Street followed, followed by Southwest First and Second Streets and Southwest First and Second Avenues, which ran from Flagler Street to the river.

More people drifted in, and stores and rough buildings were hastily constructed until 50 separate business establishments were in operation at the end of the year. One of these enterprises was the Metropolis newspaper, later known as the Miami Daily News, published until the 1950s.

Overtown Market in downtown Miami, Florida, is a predominantly African-American neighborhood that was called “Colored Town” in the days of Jim Crow segregation. Photo by Carol Highsmith, 2020.

While work on the hotel proceeded, other civic movements were going on. There was no need now for the mail carrier, Ned Pont, of Coconut Grove, to make the arduous weekly journey to Lake Worth. The town now had its own post office and moved, by petition, to the north banks so the people would not have to ferry across to Brickell’s store for their mail. The Metropolis began a campaign for better streets, especially to the wharf on Biscayne Bay, where the then-existing footpath “played havoc with patent leather shoes and the bottoms of one’s Sunday pants.” Flagler Street was graded to the bay, and Second Avenue was graded from Flagler to Southeast Second Street.

The black population provided the primary labor force for the city’s building. Clauses in land deeds confined blacks northwest of Miami, known as “Colored Town” (today’s Overtown.) Other settlements within Miami’s limits were Lemon City (now Little Haiti) and Coconut Grove. Settlements outside the city limits were Biscayne, in present-day Miami Shores, and Cutler, in present-day Palmetto Bay. Many of the settlers were homesteaders attracted to the area by the offer of 160 acres of free land by the United States federal government.

The closing days of the year were marked by a disastrous fire that started Christmas morning in E.L. Brady’s general store. There was no fire-fighting apparatus. The blaze gained headway, ignited the frame structure on the opposite side street, and destroyed all the blocks’ buildings.

Henry Flagler’s Royal Palm Hotel opened on January 16, 1897. Sitting on the north bank of the Miami River, overlooking Biscayne Bay, it was one of the first hotels in the Miami area. Five stories tall with a sixth-floor salon, the Royal Palm Hotel featured the city’s first electric lights, elevators, and swimming pool. Flagler cut a channel across the bay so guests could bring their yachts to the Royal Palm Hotel docks, and Miami experienced its first tourist season as wealthy northerners spent the winter here.

In 1898, Dan Roberts, with three companions, penetrated the wilds south of Miami, paving the way for homesteaders in that rich agricultural region now known as the Redlands. In October, the people of Lemon City had a ball to aid in building the Lemon City and Miami Rock Road.

In 1899, the county records were moved to Miami, where they remained. The first county offices in Miami were located in a frame building near the river, and a jail was built.

On January 23, 1900, Henry Flagler deeded lots on the south side of West Flagler Street east of the railroad to the city for municipal purposes. That year, 1,681 people lived in Miami.

In 1901, the county floated a bond issue to finance the construction of a courthouse, but the offices remained in the old river warehouse until 1904, when the large two-story stone building was built. In 1907, a firehouse was built, and in 1909, a city hall was erected.

On September 15, 1903, F.B. Stoneman began publishing the Miami Evening Record, the precursor to the present-day Miami Herald.

In 1909, Carrie Nation invaded the city in a whirlwind campaign against alcohol. She charged county and city officials with slackness in law enforcement and confronted them with a bottle of whiskey bought in a saloon on the Sabbath.

Miami had a population of 5,471 in 1910 and continued to grow rapidly until World War II.

Miami Beach was developed in 1913 when John Collins completed a two-mile wooden bridge. That year, six years before Congress adopted the Eighteenth Amendment, prohibiting the production, sale, and transportation of alcohol for consumption. Dade County voted dry by 976 to 860.

Flagler remained vital and energetic until his death at Palm Beach in 1913. A month after Flagler’s death, John S. Collins, then 76, opened his 2-mile wooden bridge to Miami Beach. Two years later, a new city was incorporated, and the new ship channel opened, making Miami’s port dream a reality.

By the summer of 1916, the population had increased to 1,500. On July 28, 343 registered voters met and elected Joseph A. McDonald, one of Flagler’s lieutenants and chairman. The city’s name was adopted, the boundary lines were established, and an official seal was approved. John B. Reilly was eleMayormayor.

In 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I, Miami became a training center for three branches of the government’s defense forces. Dinner Key was established as a naval aviation base at Coconut Grove in 1917. The Navy operated an aerial bombing training station opposite the Royal Palm Hotel on the bay shore. However, when the practice annoyed guests, the station was moved to Deering Island. At the peak of its activity, about 1,000 officers and soldiers were stationed at Dinner Key. Five large hangars in triple hangar units housed the flying equipment.

In 1918, the government obtained a field west of the Miami Canal and souStreet36th Street and acquired the planes and equipment to train aviators in the Marine Corps. A group of eight officers and several men arrived in the first detachment from Bay Shore, Long Island, and were later joined by groups from Lake Charles, Louisiana; Pensacola, Florida; and Parris Island, South Carolina. Four squadrons trained at this field were sent to France and another to the Azores. The field was returned to the Curtiss Company in 1919.

Chapman Field, an army training base then, was likewise abandoned at the war’s end but reopened in 1931. Later, it was used intermittently for gunnery practice. Today, it is a public park.

Following World War I, northern businessmen established new shops and homes in Miami, creating a definite market for subdivision property. Even as late as midsummer 1924, land could be purchased at $200 to $500 per acre. Operators and syndicates opened elaborate ground-floor offices on Flagler Street. Their success was so spectacular that the demand for more subdivisions sent the land prices to $2,000-$3,000 an acre.

The population was 29,549 in 1920. As thousands moved to the area in the early 20th century, the need for more land quickly became apparent. Until then, the Florida Everglades extended within three miles of Biscayne Bay.

The Roaring ’20s saw growth in Miami, as Coral Gables opened as a carefully planned development and the first plat of Hialeah was drawn. An influx of new residents and unscrupulous developers led to the Florida land boom in the early 1920s, when speculation drove land prices high. Some early developments were razed after their initial construction to make way for more significant buildings. The city’s population now numbered over 30,000, but many vestiges of the village days remained.

In the fall of 1925, the nearby areas of Lemon City, Coconut Grove, and Allapattah were annexed, creating the Greater Miami area. That year, the real-estate bubble burst.

On January 10, 1926, the Prinz Valdemar, an old Danish warship on its way to becoming a floating hotel, ran aground and blocked Miami Harbor for nearly a month. Already overloaded, the three major railway companies soon declared an embargo on all incoming goods except food. The cost of living had skyrocketed, and finding an affordable place to live was nearly impossible.

On September 17, 1926, a hurricane was reported off Turk’s Island and headed for the mainland. It struck the Florida coast after midnight, and the first onslaughts took out the power lines and plunged Miami into darkness. The gale whipped weather-recording instruments from their moorings, scattered lumber piles, and tore at concrete-block buildings. For nearly eight hours, the wind and rain poured over the city. When daylight arrived, citizens saw vacant lots where their neighbors’ houses had been, fallen trees, limbs, bits of lumber, and other debris littered the streets, and all shrubbery was blasted and stripped of its leaves.

Then, without warning, the hurricane struck again. Debris that had settled was picked up and rained like bullets, and buildings strained and weakened from the first attack collapsed like matchwood. The downtown streets were covered with broken glass, brick-and-mortar, and cement blocks. Finally, the storm passed in the late afternoon, and people crept from their shelters again to view the havoc. There was no power, lights, water, telegraph, telephone, or other means of communication.

Nationwide headlines in newspapers throughout the Nation screamed of the death and disaster that had swept South Florida in the greatest catastrophe since the San Francisco earthquake. Immediately, donations for relief began to pour into the Red Cross and cooperating agencies, and doctors, nurses, engineers, and volunteers stormed the area. The National Guard moved in, but there was little looting and no need for martial law.

In Dade County, 113 known dead were recovered, and 854 were treated in hospitals. In Miami, 2,000 homes were destroyed and 3,000 damaged. The Category 4 storm was the 12th most costly and 12th most deadly to strike the United States during the 20th century, accruing $100 million in damage. Afterward, the catastrophic Great Miami Hurricane caused Maimi’s economic bubble to collapse, ending what was left of the boom.

One Miami icon that was grievously damaged by the 1926 hurricane was the Royal Palm Hotel. After the hurricane, it became infested with termites and was condemned and torn down in 1930.

The season that followed was one of bitterness and disappointment. Tourists were afraid of South Florida, and many stayed away. Those who did come saw the scars that remained. The setback was a terrific shock. For years, the word “boom” was taboo. City publicity pamphlets and Chamber of Commerce bulletins were hard-pressed for cheery and propitious material for almost a decade. Building construction diminished rapidly while the permanent population, based on school enrollment figures, continued growing. Taxes became increasingly difficult to collect, but the city officials were reluctant to admit a collapse in realty values or make assessment adjustments.

The assessed property valuation declined from a high of $389,648,391 in 1926 to $317,675,298 in 1928. On September 6, 1928, a new 28-story county courthouse was completed across Flagler Street.

The Great Depression followed, causing more than 16,000 people in Miami to become unemployed. As a result, a Civilian Conservation Corps camp was opened in the area.

The assessed property valuation continued dropping from $167,519,892 in 1929 to $97,871,000 in 1934.

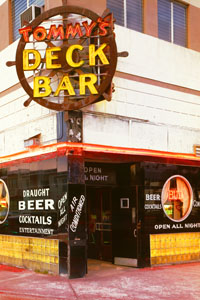

Tommys Deck Bar on Miami Beach was a popular stop in the Art Deco District. It is long gone today. Photo by Walter Smalling, 1980.

During the mid-1930s, the Art Deco district of Miami Beach was developed.

During the six months from October 1937 to March 1938, the city provided accommodations for 796,000 visitors from other states. At that time, Miami proper had 186 hotels, 978 apartment buildings, 1,157 rooming houses, numerous camp cottages, and individual homes available for lease.

During the 1937-1938 season, pari-mutuel betting totaled more than $44,000,000, and the attendance was approximately 1,000,000. Visitor expenditures in the greater Miami area were estimated at $60,000,000 annually.

By 1940, Miami was the third-biggest immigration port in the country after New York City and Los Angeles.

By the early 1940s, Miami was still recovering from the Great Depression when World War II started. Miami played an essential role in the battle against German submarines due to its location on the southern coast of Florida.

In February 1942, the Gulf Sea Frontier was established to help guard the waters around Florida. German U-boats attacked several American ships, including the Portero del Llano, which was attacked and sunk within sight of Miami Beach in May 1942. By June, more attacks forced military leaders in Washington, D.C., to increase the number of ships and men in the army group. They also moved the headquarters from Key West to the DuPont building in Miami. As the war against the U-boats grew stronger, more military bases emerged in Miami. The U.S. Navy took control of Miami’s docks and established air stations at the Opa-locka Airport and Dinner Key. The Air Force also set up bases in the local airports in the Miami area.

In addition, many military schools, supply stations, and communications facilities were established in the area. Rather than building large army bases to train the men needed to fight the war, the Army and Navy came to South Florida. They converted hotels into barracks, movie theaters into classrooms, and local beaches and golf courses into training grounds. Over 500,000 enlisted men and 50,000 officers were trained in South Florida. After the end of the war, many servicemen and women returned to Miami, causing the population to rise to nearly half a million by 1950.

After Fidel Castro rose to power in 1959, many Cubans emigrated to Miami, increasing the population. Some Miamians were upset about this, especially the African Americans, who believed that the Cuban workers were taking their jobs. The school systems also struggled to educate the thousands of Spanish-speaking Cuban children.

In 1965 alone, 100,000 Cubans packed into the twice-daily “freedom flights” from Havana to Miami. Most exiles settled in the Riverside neighborhood called “Little Havana.” By the end of the 1960s, more than 400,000 Cuban refugees were living in Dade County.

On August 7-8, 1968, coinciding with the 1968 Republican National Convention, rioting broke out in the black Liberty City neighborhood, which required the Florida National Guard to restore order. The issues were “deplorable housing conditions, economic exploitation, bleak employment prospects, racial discrimination, poor police-community relations, and economic competition with Cuban refugees.”

The 1970s was a formative period for Miami, as the city became a news leader due to several national headline-making events throughout the decade. The Miami Dolphins had their record-breaking undefeated 1972 season. During the 1972 presidential election, the Democratic and Republican National Conventions were held in nearby Miami Beach. Florida International University, the region’s first state university, opened in September 1972. Significant advancements in the arts also contributed to the development of Miami’s cultural institutions.

In 1972, Florida International University was founded in western Miami-Dade County, asserting Miami’s place in higher education in the United States.

The mid-1970s were a period of extensive Cuba-related terrorist activities, with dozens of bombings, leading the Miami News to call Miami the explosion capital of the country.

In December 1979, police officers pursued motorcyclist Arthur McDuffie in a high-speed chase after he made a provocative gesture toward a police officer. The officers claimed that the chase ended when McDuffie crashed his motorcycle and died. However, the coroner’s report provided a different conclusion. One officer testified that McDuffie fell off his bike on an Interstate 95 on-ramp. When the police reached him, he was injured but still alive. The officers removed his helmet, beat him to death with their batons, put his helmet back on, and called an ambulance, claiming it had been a motorcycle accident. Eula McDuffie, the victim’s mother, told the Miami Herald a few days later, “They beat my son like a dog. They beat him just because he was riding a motorcycle and because he was black.” After a brief deliberation, a jury acquitted the officers involved in the case. In response to the verdict, one of the worst riots in U.S. history, known as the Liberty City Riots, erupted in May 1980. By the time the rioting ceased three days later, over 850 people had been arrested, and at least 18 people had died. Property damage was estimated at around $100 million.

The Mariel Boatlift between April 15 and October 31, 1980, was a mass emigration of Cubans who traveled from Cuba’s Mariel Harbor to the United States. It brought 150,000 Cubans to Miami. Unlike the previous exodus of the 1960s, most of the Cuban refugees arriving were poor, some having been released from prisons or mental institutions. During this time, many of the middle-class non-Hispanic whites in the community left the city, often referred to as the “white flight.”

Miami also began to see an increase in immigrants from other nations, such as Haiti. As the Haitian population grew, the area known today as “Little Haiti” emerged, centered on Northeast Second Avenue and 54th Street.

In the 1980s, Miami became one of the United States’ most significant transfer points for cocaine from Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru. The drug industry brought billions of dollars into Miami, which were quickly funneled through front organizations into the local economy. Luxury car dealerships, five-star hotels, condominium developments, glamorous nightclubs, significant commercial developments, and other signs of prosperity began rising all over the city. However, as the money arrived, so did a violent crime wave that lasted through the early 1990s.

By 1990, Miami’s population was only about 10% non-Hispanic white, compared to 1960, when it was 90% non-Hispanic white.

In 1992, Hurricane Andrew caused more than $20 billion in damage just south of the Miami-Dade area.

In 1994, the Clinton Administration announced a significant change in U.S. policy to prevent another Mariel Boatlift. In a controversial action, the administration announced that Cubans intercepted at sea would not be brought to the United States but instead would be taken by the Coast Guard to U.S. military installations at Guantanamo Bay or Panama. During eight months, beginning in the summer of 1994, over 30,000 Cubans and more than 20,000 Haitians were sent to live in camps outside the United States.

After several financial scandals involving the Mayor’s office and City Commission during the 1980s and 1990s, Miami was named the United States’ fourth poorest city by 1996. With a budget shortfall of $68 million and its municipal bonds given a junk bond rating by Wall Street, in 1997, Miami became Florida’s first city to have a state-appointed oversight board assigned to it. The same year, city voters rejected a resolution to dissolve the city and make it one entity with Dade County. The City’s financial problems continued until political outsider Manny Diaz was elected Mayor of Miami in 2001.

In the latter half of the 2000-2010 decade, Miami saw an extensive boom of high-rise architecture, dubbed a “Miami Manhattanization” wave. This included constructing many of the city’s tallest buildings, with nearly 20 of the city’s 25 tallest buildings finished after 2005. This boom transformed the look of downtown Miami, which is now considered to have one of the largest skylines in the United States, ranked behind New York City and Chicago.

The $700 million Port Miami Tunnel, which connects Watson Island to Port Miami on Dodge Island, was opened in 2014. It connects Port Miami to the Interstate Highway system and Miami International Airport via Interstate 395.

Today’s Miami is renowned as a metropolitan playground. While many flock to Miami for its sparkling beaches and sizzling nightlife, the culture, fashion, and culinary delights keep them returning. From the arts to the Everglades, from sunning and surfing to dinner and dancing, Miami provides many things to keep visitors and residents entertained. While away the day on the beachfront, watch beautiful people parade down Miami’s pastel-colored Ocean Drive. Check out the latest trends in fashion and art in the chic streets of South Beach. Head downtown for an evening of sophisticated entertainment to catch the Miami City Ballet, the Florida Grand Opera, and the New World Symphony at the Arsht Center for Performing Arts. Miami offers some of the country’s most fabulous national parks and reserves. You can go boating and scuba diving at Biscayne National Park, island-hopping in Dry Tortugas National Park, or canoe through subtropical wilderness in Everglades National Park.

As of 2020, Miami is a majority-minority city, with nearly 65% of its 400,000 residents claiming Latin American heritage.

Miami is a major center and leader in finance, commerce, culture, the arts, and international trade. Its metropolitan area is by far the most significant urban economy in Florida.

Downtown Miami has among the largest concentrations of international banks in the U.S. and is home to several large national and international companies. Port Miami, the city’s seaport, is the busiest cruise port in the world in terms of both passenger traffic and cruise lines.

The Miami metropolitan area is the second-most visited city or metropolitan statistical area in the U.S. after New York City, with over four million visitors in 2022.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See:

Bucket List Attraction in Each State

Sources:

Federal Writers’ Program; Miami and Dade County, Florida; Works Projects Administration, 1941.

GPA Publications

Office of the Historian

Wikipedia- History of Miami

Wikipedia – Miami, Florida