The Tequesta (tuh-KES-tuh) people were a small, peaceful Native American tribe on the Southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. Also known as the Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, and Vizcayno, they were among the first tribes to settle near Biscayne Bay in the present-day Miami area. Living in the region since the 3rd century B.C. in the late Archaic period, they remained there for about 2,000 years. The archaeological record of the Glades culture, which included the area occupied by the Tequesta, indicates a continuous development of an indigenous ceramics tradition from about 700 B.C. until after European contact.

Like all of Florida’s original inhabitants, the Tequesta derived from Mound-building ancestors that populated the east coast. One of the first tribes in South Florida, they lived on Biscayne Bay in what is now Miami-Dade County and further north in Broward County, at least as far as Pompano Beach. Sometimes, they occupied the Florida Keys and may have had a village on Cape Sable, at the southern end of the Florida peninsula.

Their central town, called “Tequesta by the Spaniards, in honor of the chief, was on the north bank of the Miami River. The Tequesta lived in “huts” and established their villages at the mouths of rivers and streams, inlets from the Atlantic Ocean to inland waters, and barrier islands and keys. The chief lived in the main village at the mouth of the Miami River. The Tequesta changed their habitation during the year. Most of the inhabitants of the main village relocated to barrier islands or the Florida Keys during the worst of the mosquito season, which lasted about three months.

Diorama of Calusa king receiving tribute from a Tequesta chief in the Florida Museum of Natural History, courtesy of Wikipedia.

The Calusa of the southwest coast of Florida dominated the Tequesta. The Tequesta were closely allied to their immediate neighbors to the north, the Jaega. While the resources of the Biscayne Bay area and the Florida Keys allowed for a somewhat settled non-agricultural existence, they were not as rich as those of the southwest Florida coast, home of the more numerous Calusa.

The Tequesta language was probably closely related to the language of the Calusa on the southwest Florida coast and the Mayaimi, who lived around Lake Okeechobee in the middle of the lower Florida peninsula.

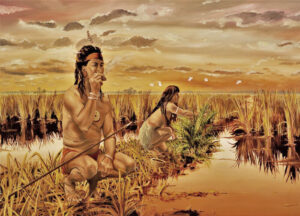

The Tequesta did not practice any form of agriculture. Instead, they fished, hunted, and gathered the fruit and roots of local plants. Most of their food came from the sea. Escalante de Fontanedo, the only survivor of a Spanish vessel wrecked on the Florida Keys in 1545, was the first white man to spend any time in South Florida. During the 17 years of his captivity among the Calusa Indians, he was permitted to explore the peninsula and visit the camps of various tribes. He described the Tequesta diet as “fish, turtle and snails, and tunny and whale.” The “sea wolf” (Caribbean monk seal) was reserved for the upper classes. Venison was also popular; deer bones, such as terrapin shells and bones, are frequently found in archeological sites. Sea turtles and their eggs were consumed during the turtles’ nesting season.

The Tequesta were expert wood carvers who made dugout canoes used along the coast and deep into the Everglades. Marriages often sealed alliances to maintain political relationships with neighboring tribes.

Clothing was minimal. The men wore loincloths made from deer hide, while the women wore skirts of Spanish moss or plant fibers hanging from belts.

The first record of European contact with the Tequesta was in 1513 when Juan Ponce de Leon sailed into a harbor he called “Chequesta,” now called Biscayne Bay.

In 1565, one of the ships in Pedro Menendez de Aviles‘ fleet took refuge from a storm in Biscayne Bay. The main Tequesta village was located there, and Menendez was well received. When they left Tequesta, the chief’s nephew journeyed with the Jesuit priests to Havana to be educated. The chief’s brother went to Spain with Menendez, where he converted to Christianity.

In March 1567, Menendez returned to the Tequesta and established a mission within a stockade near the south bank of the Miami River below the native village. Menendez left a contingent of 30 soldiers and Jesuit brother Francisco Villareal, who had learned some of the Tequesta language from the chief’s nephew in Havana.

Villareal felt he had been winning converts until the Spaniards accidentally killed the chief’s uncle, who then burned the settlement and fled to the Everglades. The Indians returned to attack the garrison, but most soldiers escaped and retreated to St. Augustine. Brother Francisco was forced to abandon the mission but returned when the chief’s brother returned from Spain. The mission was abandoned in 1570.

Estimates of the number of Tequesta at the time of initial European contact range from 800 to 10,000, while estimates of the number of Calusa on the southwest coast of Florida ranged from 2,000 to 20,000. Occupation of the Florida Keys may have swung back and forth between the two tribes. Although Spanish records note a Tequesta village on Cape Sable, Calusa artifacts outnumber Tequesta artifacts by four to one at its archaeological sites.

Beginning in 1703, the constant pressure imposed by invading Creek Indians and other northern tribes pressed many tribes down the peninsula, forcing the few remaining Calusa and Tequesta to the Islands. Many died as a result of settlement battles, slavery, and disease.

In 1704, the Spanish government resettled Florida Native Americans in Cuba so that they could be indoctrinated into the Catholic faith. The first group of these Native Americans, including those from Key West, arrived in Cuba in 1704, and most, if not all of them, soon died.

In 1710, another 280 Florida Native Americans were taken to Cuba, where almost 200 soon died. The survivors were returned to the Keys in about 1716. In 1732, some Native Americans fled from the Keys to Cuba.

During the years that followed, the name Tequesta disappeared. What happened to them is a matter of conjecture. In 1743, Francisco Javier Alegre said that these islands were inhabited by Indians who had Calusa and Tequesta as ancestors.

The Tequesta left behind an archaeological site called the Miami Circle. Dr. Robert S. Carr discovered the site on the south bank of the Miami River’s mouth in 1998. The 38-foot diameter ring of post holes carved into bedrock is believed to be somewhere between 1,700 and 2,000 years old. The circle is the foundation of a wooden structure built by the ancestors of the Tequesta people in what was possibly their capital. On February 5, 2002, the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was declared a National Historic Landmark on January 16, 2009. The site’s well-preserved outline of American Indian architecture, artifacts indicating regional and long-distance trade, ceremonial use of animals, and association with the Tequesta people contribute to its national significance.

A waterfront park managed by History Miami opened in 2011. The circle remains buried to protect it, while an audio tour and several panels describing it are available to the public. It is located at 401 Brickell Avenue in Miami, Florida.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, January 2025.

Also See:

List of Notable Native Americans

Native American Heroes and Legends

Native American Photo Galleries

Sources:

Florida Center for Instructional Technology

Kirsten Hines

Trail of Florida’s Indian Heritage

Wikipedia