The fifth president of the United States, James Monroe, was a statesman, lawyer, and diplomat who served as president from 1817 to 1825. He was the last of the Founding Fathers to become president, and, like four of his predecessors, a native of Virginia.

Monroe’s early life was rooted in the rural setting of Westmoreland County. He was born at home on April 28, 1758, to Spence and Elizabeth Jones Monroe. One of five children, the family lived about one mile from the present-day unincorporated community of Monroe Hall, Virginia. His father, a moderately prosperous planter and slave owner, also practiced carpentry, reflecting the simplicity and self-sufficiency of their rural lifestyle.

Monroe received his early education at home from his mother, Elizabeth, and studied at the Campbell Town Academy from ages 11 to 16. However, he only attended this school for 11 weeks each year, as he needed to work on the farm during the rest of the time. During this period, Monroe developed a lifelong friendship with an older classmate, John Marshall.

Monroe’s mother died in 1772, and his father died two years later. Inheriting their property, including slaves, 16-year-old Monroe was forced to withdraw from school to support his younger brothers. His childless maternal uncle, Judge Joseph Jones, became a surrogate father to Monroe and his siblings. A member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, Jones took Monroe to the capital of Williamsburg, Virginia, and enrolled him in the College of William and Mary. Jones also introduced Monroe to important Virginians such as Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and George Washington.

In 1774, opposition to the British government grew in the Thirteen Colonies in reaction to the “Intolerable Acts,” and Virginia sent a delegation to the First Continental Congress. Monroe became involved in opposing Lord Dunmore, Virginia’s colonial governor, and stormed the Governor’s Palace.

In early 1776, James Monroe left college to join the 3rd Virginia Regiment under General George Washington during the Revolutionary War. At just under 19 years old, he served as a lieutenant at the Battle of Trenton, where he successfully led a squad that captured a Hessian battery just as it was about to open fire. Both Monroe and George Washington were wounded during this battle. After recovering from his injury, Monroe joined the Virginia Militia in 1777 and was appointed lieutenant colonel. He distinguished himself for bravery and skill in the battles of Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. Eventually, he left the army to study law under Thomas Jefferson.

In 1780, the British invaded Richmond, and as Governor, Jefferson commissioned Monroe as a colonel to command the militia and act as a liaison to the Continental Army in North Carolina. Afterward, Monroe resumed studying law under Jefferson. In 1782, he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. The following year, when he was 25 years old, he was a delegate to the Continental Congress and was present at Annapolis, Maryland, when George Washington resigned from his military commission.

He originated the first movement in 1785, which led to the constitutional convention in 1787.

On February 16, 1786, Monroe married Elizabeth Kortright, the daughter of Hannah Aspinwall Kortright, and Laurence Kortright, a wealthy trader and a former British officer. Monroe met her while serving in the Continental Congress. After a brief honeymoon on Long Island, New York, the Monroes returned to New York City to live with her father until Congress adjourned. The couple would eventually have three children.

He was a member of the Virginia legislature in 1787, and the following year, he was a delegate in the State convention to consider the Federal Constitution. He took part with Patrick Henry and others in opposition to its ratification, yet he was elected one of the first United States Senators from Virginia under that instrument in 1789. At that time, he moved his family to Charlottesville, Virginia.

He was elected a senator on November 9, 1790, and became a Democratic-Republican Party leader. He left the Senate in May 1794 to serve as President George Washington’s ambassador to France. President George Washington recalled him in 1796.

Monroe won the election as Governor of Virginia in 1799 and strongly supported Thomas Jefferson’s candidacy in the 1800 presidential election. He served as governor for three years when President Thomas Jefferson appointed him as an extraordinary envoy to act with Mr. Livingston at the court of Napoleon. As President Jefferson’s special envoy, Monroe helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase, through which the United States nearly doubled in size.

In 1799, he bought an estate in Charlottesville, Virginia, known as Ash Lawn-Highland.

In 1808, he unsuccessfully challenged James Madison for the Democratic-Republican presidential nomination. However, in 1811, he joined Madison’s administration as Secretary of State. During the later stages of the War of 1812, Monroe simultaneously served as Madison’s Secretary of State and Secretary of War. His wartime leadership, ambition, and energy, together with the backing of President Madison, made him the Republican choice for the Presidency in 1816. He was re-elected in 1820.

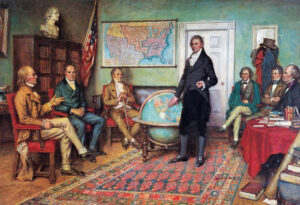

As president, James Monroe signed the Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri as a slave state and banned slavery north and west of Missouri permanently. Regarding foreign affairs, Monroe and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams supported a conciliatory policy towards Britain while advocating for expansion against the Spanish Empire. In the 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty with Spain, the United States secured Florida and established its western border with New Spain. In 1823, Monroe announced the United States’ opposition to European colonialism in the Americas, effectively asserting U.S. leadership and dominance in the hemisphere. This declaration became a landmark moment in American foreign policy.

James Monroe’s Ash Lawn-Highland home is in Virginia, courtesy of Wikipedia.

At the end of his second term, in 1825, Monroe retired from office and made his residence in Loudon County, Virginia. Financial difficulties soon plagued him. His wife Elizabeth died in 1830, and James moved to New York City in early 1831, where he lived with his daughter Maria Hester Monroe Gouverneur, who had married Samuel L. Gouverneur. Monroe’s health began to fail by the end of the 1820s.

He died on July 4, 1831, at age 73, from heart failure and tuberculosis. He shared his death date with Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, who also died on the anniversary of U.S. independence.

Monroe was initially buried in New York at the Gouverneur family’s vault in New York City’s Marble Cemetery. However, 27 years later, in 1858, his body was re-interred at the President’s Circle in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. The James Monroe Tomb is a U.S. National Historic Landmark.

Historians have generally ranked James Monroe as an above-average president.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Lossing, Benson John; Eminent Americans, Volume II; American Publishers Corporation, New York, 1890.

Morris, Charles; A New history of the United States: The greater Republic; 1899

Whitehouse.gov (archived)

Wikipedia