Dominguez and Escalante Expedition.

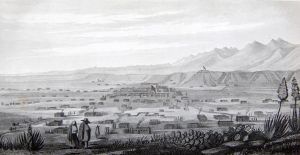

The Dominguez–Escalante Expedition was a Spanish exploration conducted in 1776 by Franciscan priests Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante. Its purpose was to find an overland route from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to their Roman Catholic mission in Monterey, California. It was one of the last significant expeditions conducted by the Spanish Crown in the American Southwest, and no European had ever traveled from one point to another.

On July 29, 1776, the two friars began the journey, accompanied by eight volunteers outfitted with saddle horses, pack animals, and cattle. They aimed to find a route north of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River over Comanche territory, where Spaniards had experienced violent encounters in previous decades. Ultimately, the expedition made a wide loop, traveling north instead of west, and covered a vast territory in Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. These detours would take them several months to complete.

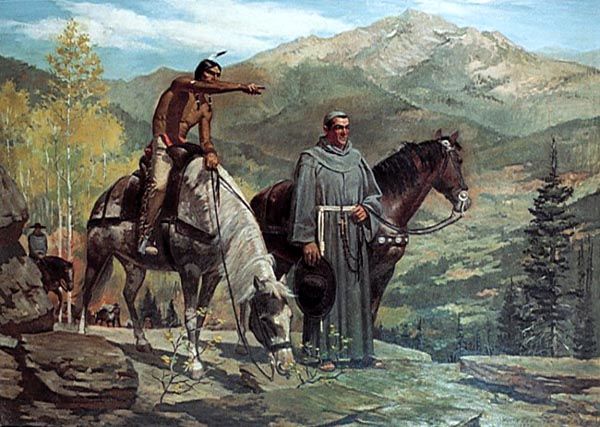

Franciscan friar Atanasio Dominguez was placed in charge. Silvestre Velez de Escalante, who was familiar with the Indian Tribes on the northern frontier, kept a journal that recorded daily events. Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, acting as the expedition’s cartographer, accompanied the men from Santa Fe through numerous unexplored portions of the American West. Multi-talented, Pacheco was an army engineer, merchant, Indian fighter, government agent, rancher, and artist.

During their trip, they documented the route they took. They provided detailed information about the “lush, mountainous land filled with game and timber, strange ruins of stone cities and villages, and rivers showing signs of precious metals.”

Other men who began the expedition in Santa Fe included:

-Don Juan Pedro Cisneros, Alcalde mayor of Zuni Pueblo

-Don Joaquín Lain was a native of Santa Cruz in Castilla la Vieja and a citizen of Santa Fe at the time of the expedition.

-Lorenzo Olivares from La Villa del Paso, a citizen of El Paso at the time of the expedition

-Andres Muniz from Bernalillo, New Mexico, served as an interpreter of the Ute language.

-Lucrecio Muniz was the brother of Andres Muniz, who was from Embudo, north of Santa Fe.

-Juan de Aguilar was born in Santa Clara, New Mexico.

-Simon Lucero, a servant to Don Pedro Cisneros, may have been Zuni.

The expedition was small, making the journey all the more dangerous. They brought few weapons, and the Ute Indians they encountered early in the expedition warned the priests that they would need them as they ventured further from settled areas.

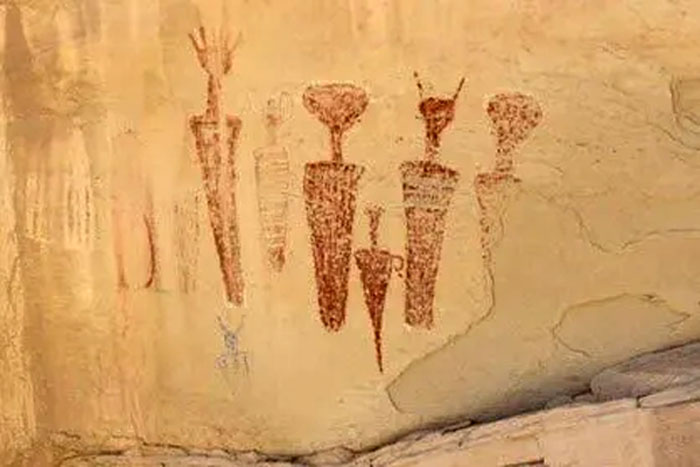

On the first night of the journey, they stayed overnight at the Santa Clara Pueblo, north of Santa Fe. From there, they traveled to Santa Rosa de Abiquiu Pueblo, then north and northwest to a location near present-day Dulce, New Mexico. As the expedition moved on, they observed and named prominent landmarks. They entered Colorado through Arboles, Ignacio, Durango, and Hesperus. On August 10, they camped at the base of the La Plata Mountains near the current Mesa Verde National Park. Escalante and Dominguez were the first white men to find and record the ancestral Puebloan ruins in southwestern Colorado.

The men traveled north and west of the San Juan Mountains, crossing the Dolores River several times, and camped along its banks northeast of present-day Cahone. There, they met two Native American slaves, whom they called Genízaro and Coyote, who joined the group.

Continuing northwest, they traveled through a canyon before reaching an area near the current Egnar and along the San Miguel River, to a location about five miles west of Nucla, Colorado. The land became increasingly arid, with less pasture land and insufficient water for the horses, and the canyons were rugged. Seeing signs of settlements and realizing they needed assistance, they searched for Ute Indians, who might serve as their guides.

Finally, northeast of Nucla, where the San Miguel River meets the Dolores River, the group met a member of the Ute tribe. They camped along a tributary creek of the San Miguel River and traveled east through the Uncompahgre National Forest onto the Uncompahgre Plateau. They went to an area near Montrose and met with a Ute chief. Learning of the Timpanogo Ute men in the area, the party resumed traveling northwesterly, crossing the north fork of the Gunnison River and coming to the site of what is now Hotchkiss.

Continuing travel to the northeast, the expedition reached the area of Bowie on September 1, encountering 80 Timpanogo Ute men on horseback. After meeting with the chief and his sons, Father Dominguez preached through Andres Muniz, the interpreter. The Ute men strongly encouraged the expedition to turn back because they would encounter Comanche Indians on their trip west. The Ute worried the Spanish governor would blame them if the expedition were harmed. Violating the agreement on which the expedition had gained permission for the journey through Ute territory and its spiritual purpose, the interpreter, Muniz, and his brother, Lucrecio, traded goods for guns.

Having arranged for guides, they traded their horses for fresh ones from the Ute. They gained agreement to continue the expedition, guided by “Silvestre” and a boy they named “Joaquín.”

“Silvestre,” named after Silvestre Escalante, from present-day Utah, was the leading Native guide from Colorado to Utah. Due to his recognition among the Ute tribes, the explorers enjoyed safe passage.

The party traveled through the Grand Mesa National Forest to the south side of Battlement Mesa. The group crossed the Colorado River at Una, Colorado, and soon met some Ute who helped resolve questions with “Silvestre” about the best route to take next. The party learned that the Comanche had moved to the east, away from their planned route.

Having traveled north and west through the Canyon Pintado, just south of Rangely, Colorado, the expedition entered present-day Rio Blanco County, Colorado, which is named for the White River, which flows into Utah at its western border. They crossed the White River just east of Rangely on September 10, and the land became flatter after weeks of mountain, canyon, and mesa travel.

In the middle of September 1776, the party arrived around the current-day Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado, killing a bison somewhere near the Yampa Plateau. From there, they continued following Cliff Creek, observing Blue Mountain and Musketshot Springs, which they recorded as “a musket shot apart from each other.” The Friars were impressed by the Green River, which they named the San Buenaventura, and wrote that the river flows “between two lofty stone hogbacks which, after forming a sort of corral, come so closely together that one can barely make out the gorge through which the river comes,” a very apt description of Split Mountain Canyon as seen from the south. They continued until they made camp on the riverbank about a mile from where they intended to ford it and camped by a big stand of cottonwoods where one of the party members carved “Year of 1776.”

The Dominguez-Escalante party continued their trek into the Uinta Basin of Utah, traveling through what are now the communities of Jensen, Roosevelt, Duchesne, and Myton, and extolling each as an excellent place for settlement. Upon arriving in Utah Valley and finding friendly Ute from the same band as their guides, the group remarked at their good fortune and quickly promised to return within the year, settle the area, and preach the gospel.

The explorers reached Utah Lake, near Salt Lake City, on September 23, relying on information from Indian guides.

Silvestre and Joaquín were given woolen cloth and red ribbon, which they used to adorn themselves before entering the village of their people. Silvestre tied the cloth around his head, with the long ends hanging down his back, and wore a cloak that had been given to him earlier. The men traveled out of the canyon into a meadow and entered the Utah Lake Valley, where they found the lake they called the Lake of the Timpanogos Tribe.

A small contingent, including Silvestre, Joaquín, Muniz, and Dominguez, traveled to a Native American village on the Provo River, north of Provo and east of Utah Lake. Men came out to meet them, brandishing weapons, but as soon as they recognized Silvestre, the men from the expedition were warmly welcomed and embraced. They met with the tribal leader, Chief Turunianchi. The Native Americans were shocked to learn they had traveled safely through Comanche territory. The purpose of the visit was explained, including the desire to share their faith.

Low on provisions, the loss of their guide, and the fact that winter was beginning to set in caused great trepidation. The expedition members drew lots to see if they would continue toward Monterrey or return to Santa Fe. After some resistance, the party decided to turn back toward Santa Fe rather than press on to California.

Dominguez asked for another guide to continue their journey. Joaquín and a boy they named Jose María, also about 12 years old, would continue the journey. The fathers gave gifts to the tribe and received a large quantity of dried fish for their travels.

The group left Silvestre’s village near Spanish Fork on September 25 and traveled southwest over unknown territory. They camped near sites in Springville, Payson, Starr, Levan, and Scipio. They encountered several small groups of Native Americans, who were mostly friendly and social.

After Scipio, they had difficulty finding pastureland and water fit for drinking. To add to their troubles, Jose María, the new guide they had asked to lead them, abandoned the party when he witnessed a servant being punished, and the expedition had no way of knowing which way to continue. However, Joaquín continued to assist the explorers. They traveled south along Ash Creek to its confluence with the Virgin River, near modern-day Hurricane, in Washington County. Escalante’s journal suggests that the party camped atop Sand Mountain before traveling south along Fort Pearce Wash.

By October 22, they reached the Paria River. As they made their way east across Arizona, they continued to encounter difficulties due to illness, a lack of water, pastureland, and supplies.

Guided by local Native Americans, the expedition proceeded to the site of present-day Lees Ferry but found it too difficult to cross the river. They were led to a second ford of the Colorado River, where they carved steps into the canyon wall. In a translated journal, the Fathers described their difficult situation,

“In order to have the mounts [mules, donkeys, and horses] led down to the canyon mentioned, it became necessary to cut steps with axes on a stone cliff.”

After safely taking the animals down the stairs, they looked for a safe river crossing. They found a relatively easy spot with little flow to swim across. On November 7, 1776, they crossed the Colorado River. This ford, now called the Crossing of the Fathers, is submerged beneath Lake Powell.

To survive, the expedition resorted to eating many of its horses, the only remaining provisions. They turned south to visit the villages of the Hopi and Zuni Tribes and survived thanks to supplies generously provided by the Hopi. They eventually headed north along the Rio Grande to Santa Fe.

After traveling more than 2,000 miles during their six-month journey, the party finally arrived in Santa Fe on January 2, 1777.

Joaquín was baptized there in the Catholic Church upon returning to Santa Fe.

Upon Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez’s return to Santa Fe and Mexico City, he submitted a highly critical report to his Franciscan superiors regarding the administration of the New Mexico missions. His views led him to fall out of favor with the Franciscans in power, resulting in an assignment to an obscure post at a Sonoran Desert mission in northern Mexico. In 1800, he was in Janos, Sonora, Mexico. He died between 1803 and 1805.

Fray Francisco Silvestre Velez de Escalante remained in New Mexico for two years following the expedition. He died on April 30, 1780, in Parral, Mexico, while returning to Mexico City for medical treatment.

Although they failed to reach Monterrey, the Dominguez-Escalante Expedition succeeded in describing and mapping vast areas of the American West, thereby opening them up to future exploration and trade. His maps and journals were used by Lewis and Clark in 1803. One of the routes that Dominguez-Escalante helped pioneer during their travels was the Old Spanish Trail, a trade route that extended from Santa Fe to the Salt Lake Valley. It is now a designated National Historic Trail.

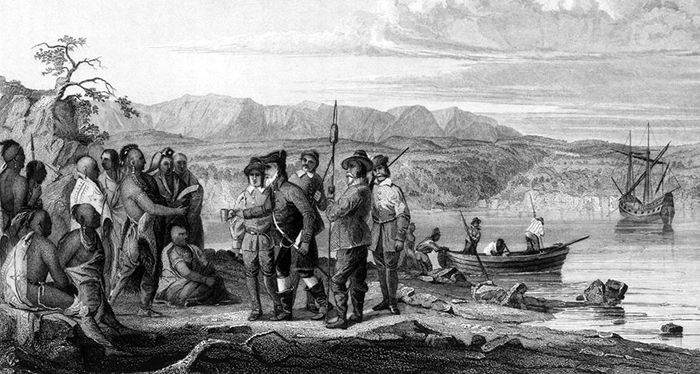

Spanish Explorers meet Native Americans.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Missions & Presidios of the United States

Old Spanish Trail – Trading Between New Mexico & California

Sources:

Bureau of Land Management

National Park Service

University of Denver (Dead Link)

Utah Humanities

Wikipedia