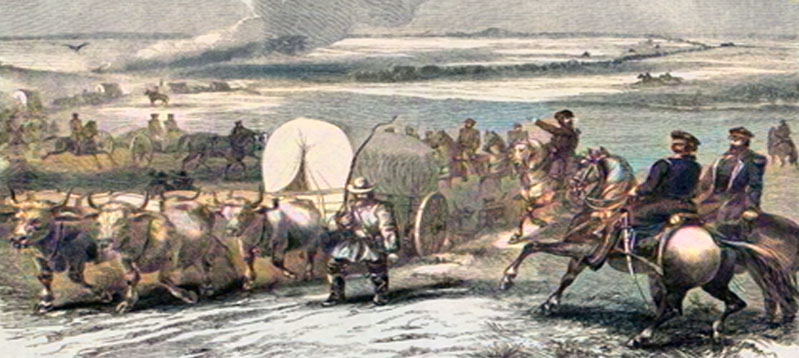

Utah Expedition by Harpers Weekly, 1858.

The Utah War, also known as the Utah Expedition and the Mormon War, was an armed confrontation in the Utah Territory between members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), also known as Mormons, and the U.S. government’s armed forces.

Taking place from May 1857 to July 1858, the conflict primarily involved Mormon settlers and federal troops, escalating from tensions over self-governance within the territory. There were several casualties, predominantly non-Mormon civilians. Although the war featured no significant military battles, it included the Mountain Meadows Massacre, where Mormon militia members disarmed and murdered about 140 settlers traveling to California.

Mormon pioneers began leaving the United States for Utah after a series of severe conflicts with neighboring communities in Missouri and Illinois resulted, in 1844, in the death of Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement. These conflicts were primarily a result of the church’s practice of polygamy, which Joseph Smith initiated as early as 1841. For a time, the Mormons attempted to keep polygamy a secret.

Church president Brigham Young organized the journey to take the Mormon pioneers to Winter Quarters, Nebraska, in 1846 before continuing to the Salt Lake Valley. Young and other church leaders knew about the Great Salt Lake Valley from trappers’ journals, explorers’ reports, and interviews with travelers familiar with the region. Leading about 12,000 Mormons from Illinois, they were determined to establish their faith beyond the reach of American laws and resentment.

Most of what would become the American Southwest at the time belonged to Mexico, but Young believed that that nation’s hold on its northern frontier was so tenuous that the Mormons could settle there free from interference.

In the spring of 1847, he led an advance party of 147 from the encampment in Nebraska to the Great Salt Lake Valley, arriving on July 24, 1847. On his arrival, he stated, “If the people of the United States will let us alone for ten years, we will ask no odds of them.” By the time they arrived, it had come under American control due to the Mexican-American War, although U.S. sovereignty would not be confirmed until 1848.

Over the next two decades, some 70,000 Mormons would follow.

Brigham Young and other LDS Church leaders believed that Utah’s isolation would secure their rights and ensure the free practice of their religion. However, the Saints struggled for years to make life pleasant and bountiful in a harsh, arid climate, and their success was modest at best.

When gold was discovered in California in 1848 at Sutter’s Mill, sparking the famous California Gold Rush, thousands of migrants began moving west on trails that passed directly through territory settled by Mormon pioneers. Utah grew and prospered during this time with trade opportunities, ending the Mormons’ short-lived isolation.

In February 1848, Mexico sealed its defeat in the Mexican-American War by signing the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ceding to the United States what is now California, Nevada, Utah, Texas, and parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. Just six months after arriving in their new Zion, the Mormons found themselves back under the authority of the United States.

In 1848, federal appointees and military parties arrived in Utah seeking to fulfill the directives and missions of the national government. However, the Mormons had developed their local courts and authority outside the established practices in other states and territories. The probate courts often resembled a religious judicial process, which caused great anxiety among territorial judges.

Following the gold seekers, Army expeditions, surveys, scientific explorers, and federal officials also came.

State-of-Deseret Mormon Flag of God’s Kingdom.

In 1849, the Mormons proposed organizing a significant portion of their inhabited territory as the State of Deseret within the United States. Their main concern was that their region be governed by leaders of their choosing rather than “unsympathetic appointees” who they feared would be sent from Washington, D.C. if granted territorial status. They believed they could preserve their religious freedom only through a state led by their church leadership.

The land they sought was vast, running from the Rocky Mountains to the Sierra Nevada range and from the new border with Mexico to present-day Oregon. Congress, guided in part by the struggle between forces opposing and condoning slavery, designated the Utah Territory in September 1850, but not before reducing the area to present-day Utah, Nevada, western Colorado, and southwestern Wyoming.

Territorial status gave the federal government greater authority over Utah’s affairs than statehood would have. But President Millard Fillmore inadvertently set the stage for a clash with his choice for the new territory’s chief executive. Acting partly in response to lobbying from a lawyer, Thomas L. Kane, a non-Mormon who had advised Mormon leaders in previous ordeals, Fillmore named Brigham Young, the LDS Church’s president, as the first governor of the new Utah Territory.

In March 1852, Utah Territory passed Acts that legalized black slavery and Indian slavery. During this period, the leadership of the LDS Church supported plural marriage. An estimated 20% to 25% of Latter-day Saints were members of polygamous households, with the practice involving approximately one-third of Mormon women who reached marriageable age.

On August 29, 1852, at a general conference of Mormons in Salt Lake City, the church leadership publicly acknowledged plural marriage for the first time. Orson Pratt, a Quorum of the Twelve Apostles member, delivered a lengthy discourse, inviting the members to “look upon Abraham’s blessings as your own, for the Lord blessed him with a promise of seed as numerous as the sand upon the seashore.” After Pratt finished, Young read aloud Smith’s revelation on plural marriage.

Brigham Young was an ardent supporter of polygamy,

marrying 56 wives during his lifetime and fathering 57 children.

The disclosure was widely reported outside the church, quashing any hopes the Utah Territory might have had for statehood under Young’s leadership. Conflicts between Young’s roles as governor of the territory and church president would only become more complicated.

The rest of American society rejected polygamy, with some commentators accusing the Mormons of gross immorality. Newspapers of the time referred to polygamy as “the enslavement of women,” called Salt Lake City a “sink of iniquity,” and labeled the church a “giant of licentiousness, lawlessness, and all evil.”

Fort Supply was established 12 miles southwest of Fort Bridger in 1853 in response to a church assignment to create a colony in the Green River Valley.

Brigham Young’s term as territorial governor expired in 1854, but he continued to serve on an interim basis.

In August 1855, Lewis Robison purchased Fort Bridger from Louis Vasquez and famed mountaineer Jim Bridger for $8,000 on behalf of the church. It served primarily as an outpost for Mormon immigrants to the Salt Lake Valley. Wasting no time, Lewis Robison torched Fort Bridger just hours after the council of war concluded. Fort Supply was burned the next day after Mormons harvested and cached most of the crops for future use. Robison estimated the “damage at Fort Bridger to be $2,000 and the damage at Fort Supply to be $50,000.

With federal appointees and military parties continuing to arrive in Utah until 1856, relations between these officials and the Latter-day Saints deteriorated into accusations, insults, and a substantial breakdown of official authority and trust.

The Presidential campaign of 1856 featured extensive denunciation of polygamy and Mormon governance in Utah, pledging “to prohibit in the territories of those twin relics of barbarism: polygamy and slavery” and insisting that Congress should take action to prohibit the practice of such.

James Buchanan, a Democrat, defeated Millard Fillmore in the 1856 election and assumed the presidency in March 1857. By then, about 40,000 Mormons, mostly from eastern states and Europe, had created dozens of communities in their “Zion.” After years of complaints, letters, reports, and affidavits from so-called runaway officials and army officers, President Buchanan decided it was time to act. However, he refused to investigate the conditions in Utah further. With his cabinet equating the Utah petitions to a declaration of war, he decided to replace Young with Alfred Cumming, a former mayor of Augusta, Georgia, who was serving as an Indian affairs superintendent based in St. Louis, Missouri. However, for reasons that are not clear, he did not notify Brigham Young that he was being replaced.

Governor Young knew of his people’s complex relations with federal officials, but he and his followers generally labeled the problems as religious persecution. He was unaware that a new governor was en route to replace him and that a small army would enforce national authority. The first indication of a gathering storm was the termination of the mail contract with the U.S. Post Office in the spring of 1857.

By April, the press in the Eastern U.S. began to speculate on who would be appointed to replace Brigham Young.

In May 1857, President Buchanan ordered Secretary of War John B. Floyd and General Winfield Scott to organize a military escort to accompany the new governor and other federal officials west and establish order, enforce the laws of the United States, and impose martial law upon the territory if necessary.

General Scott knew the small regular Army was already stretched to its limit with its far-flung missions from Florida to California, including patrolling war-torn “Bleeding Kansas.” He first estimated that the Latter-day Saints could not field more than 4,000 effective troops, which proved very realistic. Therefore, he called up about 2,500 soldiers, including two regiments of infantry and a strong cavalry support of six, later eight, companies of the Second Dragoons. Two artillery batteries were also ordered — one from the Fourth and Fifth Artillery Regiments. These units joined the Army at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, the base of operations. By then, the Army was a brigade-sized force and was the largest military operation between the Mexican and Civil Wars. Command of the campaign was given to General William S. Harney of Louisiana.

In the meantime, Secretary Floyd ordered the military bureaus under his control to prepare logistics and contracts for moving and supplying a significant military force over 1,200 miles across the frontier. Floyd arranged for the Quartermaster Department to send an officer before the main column to secure provisions, locate a suitable campsite, and arrange services among the Mormons. This advance party, led by Captain Stewart Van Vliet of the Quartermaster Department, became the most apparent symbol that the federal government did not desire a hostile conflict with the Mormons.

Soon, 2,500 troops were assembled to be dispatched to Utah. General William S. Harney was initially designated to head the campaign, but conditions in “Bleeding Kansas” caused him to remain in that state.

During this planning and organization, Buchanan’s expedition was shrouded in secrecy, making no public announcement as to his purposes before he launched the undertaking” until the official orders were issued by General Winfield Scott on May 28, 1857, for the deportation of “not less than 2,500 men.” U.S. soldier John Rosa summarized the Army’s purposes for marching on Utah as the result of the Mormons’ refusal to “put themselves under the control of the United States; therefore they sent troops to be made to obey the law of the United States.”

On June 29, 1857, U.S. President James Buchanan declared Utah in rebellion against the U.S. government and mobilized a regiment of the U.S. Army, initially led by Colonel Edmund Alexander.

In a sermon on July 5, Utah Governor Brigham Young mentioned “rumors” that the U.S. was sending 1,500–2,000 troops into the Utah Territory.

On July 13, 1857, President Buchanan appointed Alfred Cumming governor of Utah and directed him to accompany the military forces. Five days later, on July 18, Colonel Alexander and his troops began the journey to Utah.

Mormons Porter Rockwell and Abraham Owen Smoot soon learned that the Army was approaching. They then traveled to the Salt Lake Valley as fast as their horses would carry them to inform Brigham Young of the government’s plans. Arriving five days later, on the evening of July 23, they found the city almost vacant. Nearly 2,600 people were in Big Cottonwood Canyon, preparing to celebrate their tenth anniversary in the Salt Lake Valley on July 24, when riders brought word that a military force was en route to Utah. For the next few weeks, Young and his advisers discussed the meaning of the government’s actions without any word from national officials.

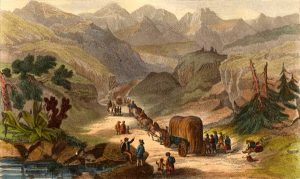

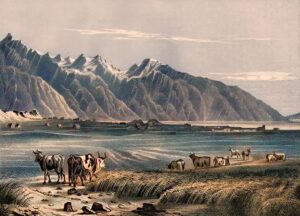

Great Salt Lake Valley, Utah.

A proclamation was issued by Governor Young, which read in part:

“Citizens of Utah: We are invaded by a hostile force, which is assailing us to accomplish our overthrow and destruction.”

Soon, it became apparent that stringent policies were needed to safeguard the Saints’ settlements, property, and lives. Food, a bartering commodity with immigrant trains, was restricted to Church members only. The complete reorganization of the Utah militia, the Nauvoo Legion, continued an effort that had begun months earlier. This was a daunting challenge, compounded by inexperienced training and combat operations leadership, a limited number of firearms, no useful artillery, inadequate equipment, and little time to train and prepare. Weapons and gunpowder were stockpiled. To arm the legion, revolvers and other firearms were produced locally. At its height, the Nauvoo Legion could field and equip only a fraction of the 4,000 men on the muster rolls. Organized into military divisions, the legion was commanded by General Daniel Wells, an accomplished leader, businessman, and Church officer. However, he had no military experience beyond militia service.

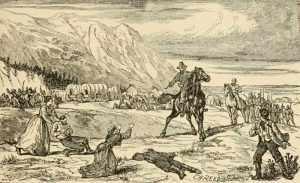

Mormon Pioneers.

The Saints’ only logical course of action was to conduct a guerrilla campaign instead of direct conventional combat. As the conflict continued, other actions included recalling missionaries from abroad and closing remote and far-flung settlements. At the same time, food, equipment, animal fodder, and all valuable stores were safeguarded for family and community needs.

Within a few weeks of the news, Nauvoo Legion officers developed a strategy and issued orders for engaging the invading Army:

“Remember, our mode of warfare is to destroy our enemies without losing our men. Waylay them, stampede their animals, cut off their patrolling parties, burn the grass and lay waste the country before them, separate them from their baggage if possible, and burn them until they are utterly destroyed and wasted away and your men all the time comparatively safe.”

The Mormons also started an all-out campaign to encourage local Native American tribes to ally themselves with the Mormons against the “Gentiles,” whose treatment of the tribes was worse than the more benign treatment by Mormons. The senior leaders traveled among the settlements, giving intense and emotional speeches to boost morale and prepare the Saints for the most dire possibilities.

On August 28, 1857, Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston was ordered to replace General Harney, who remained in Kansas, as commander of the U.S. troops.

On September 7, 1857, Captain Stewart Van Vliet of the Quartermaster Corps arrived in Salt Lake City to arrange food and forage for the incoming Army. He tried to assure Church leaders of the Army’s peaceful intentions. He was the first official contact the Saints had with either the military or the government since the problems had arisen.

Treated kindly, Van Vliet interviewed Church leaders and attended a public meeting in the Old Tabernacle. He became convinced that the Mormons were not in rebellion against the authority of the United States but that they felt justified in preparing to defend themselves against an unwarranted military invasion. Unsuccessful in making arrangements for the troops, he returned to the Army and Washington, D.C., where he became a strong advocate of peaceful reconciliation. He was accompanied by the Utah congressional delegate, John M. Bernhisel, who carried more letters to Thomas L. Kane.

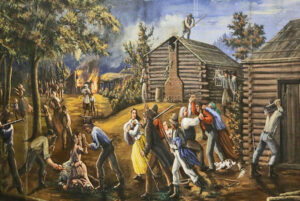

In this heated atmosphere, an immigrant California-bound wagon train that included 140 unarmed non-Mormon emigrants from Arkansas, Missouri, and other states made camp in a lush valley known as Mountain Meadows, about 40 miles beyond the Mormon settlement of Cedar City.

At dawn on September 7, 1857, the travelers were besieged by Mormon-allied Paiute Indians and Mormon militiamen disguised as Indians. Though the wagons were drawn into a circle, making a strong defensive barrier, seven were killed and 16 wounded in the first assault. The siege continued for the next five days while the wagon train resisted.

After the five-day siege, a white man bearing a white flag approached the emigrants. With a group of Mormons under John D. Lee, he told them that they had interceded with the attackers and would guarantee the emigrants safe passage out of Mountain Meadows if they would turn over their guns. When the emigrants accepted the offer, the wounded and the women and children were led away first, followed by the men, each guarded by an armed Mormon. After half an hour, the guards’ leader ordered them to halt. Every man in the emigrant party was shot from point-blank range, according to eyewitness accounts. The women and older children fell to bullets, knives, and arrows. Only 17 people — all children under seven — were spared.

For decades afterward, Mormon leaders blamed Paiute Indians for the massacre. The Paiute took part in the initial attack and, to a lesser degree, the massacre, but historians have established that Mormons were responsible. This event was later called the Mountain Meadows Massacre, and the motives behind the incident remain unclear. However, during the Utah War, the massacre was an act related to war hysteria, which led some Latter-day Saints to become crazed in their zeal against their perceived enemies.

Leaking news of the massacre, along with ongoing press chatter about the Latter-day Saints’ then-practice of polygamy and complaints of injustice in Utah Territorial courts, fanned outrage against the Mormons.

In the meantime, Colonel Johnston had traveled west and arrived at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, by the second week of September. He assigned an escort of 40 dragoons to accompany him on a hasty march to overtake his disorganized, brigade-sized command. There, he met newly appointed territorial governor Alfred Cumming of Georgia and the governor’s entourage, consisting of his wife, several new federal judges, and others. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, commanding the Second Dragoons, was reorganizing and outfitting several regiment companies for the march to Utah. Cooke would lead his regiment and escort the governor and his party across the sparse high desert of Wyoming through a dreadful early winter season.

At about the same time, Brigham Young proceeded with his plans. On September 15, 1857, he proclaimed martial law, forbidding “all armed forces of every description from coming into this Territory, under any pretense whatsoever.”

He ordered the Nauvoo Legion to prepare for the invasion, and 1,250 men were immediately sent to Echo Canyon. Daniel H. Wells instructed the militia to annoy the incoming Army in every possible way.

Preparations for defense were accelerated in nearly every Utah community. He also instructed village bishops to prepare to burn everything should hostilities break out.

Rather than engaging the Army directly, the Mormon strategy hindered and weakened them. Daniel H. Wells, Lieutenant-General of the Nauvoo Legion, instructed Major Joseph Taylor:

“On ascertaining the locality or route of the troops, proceed at once to annoy them in every possible way. Use every exertion to stampede their animals and set fire to their trains. Burn the whole country before them and on their flanks. Keep them from sleeping by night surprises; blockade the road by felling trees or destroying the river fords where possible. Watch for opportunities to set fire to the grass on their windward so as, if possible, to envelop their trains. Leave no grass before them that can be burned. Keep your men concealed as much as possible, and guard against surprise.”

On September 18, 1857, U.S. troops left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for Utah. The Army’s westward march was poorly led and unorganized, leading to the misuse and loss of government property. Nonetheless, the march was supported by American soldiers’ skilled discipline and selfless service. Before Colonel Johnston arrived at Ham’s Fork in western Wyoming, the Utah expedition was spread out in a disorganized column vulnerable to attack. For weeks, Mormon militia hovered near the various infantry units and wagon trains.

Then, on October 5, 1857, Lot Smith led the Nauvoo Legion on a guerrilla-style attack on the provision wagons of the United States Army, in which 52 wagons were burned, and hundreds of heads of livestock were scattered.

“I will fight until there is not a drop of blood in my veins. Good God! I have wives enough to whip out the United States.”

— Mormon Apostle Heber C. Kimball.

Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, who had replaced General William Harney, was appointed commander on August 29. By this time, the Army had been en route to Utah for over a month. The senior officer of the expedition, Colonel Edmund B. Alexander of the 10th Infantry, assumed leadership responsibilities until Johnston caught up to the group.

On November 3, Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston caught up with Colonel Alexander and replaced him as commander. Johnston ordered the regiment to establish winter quarters near Fort Bridger, which the Mormons had burned, and to delay the move to Salt Lake City until next spring.

The soldiers suffered through the winter, but Johnston maintained a strong discipline and modest recreational diversions. Meanwhile, Mormon soldiers guarded the main entrance to the Great Basin at Echo Canyon. Eventually, most of the Mormons went home, leaving only a small detachment to watch the federal Army.

In February 1858, Thomas Kane, a friend of the Mormons, arrived in Salt Lake to act as a negotiator between the Mormons and the approaching Army. Through careful negotiation, war was averted, and Governor Alfred Cummings was promised acceptance in Utah.

Kane soon visited Camp Scott and persuaded Governor Alfred Cumming to travel to Salt Lake City without his military escort under the guarantee of safe conduct. Johnston was appointed commander of the new Department of Utah and received an honorary promotion to brigadier general.

On March 23, 1858, Brigham Young implemented a scorched-earth policy. Salt Lake City was vacated, and most saints relocated to settlements south of the Salt Lake Valley.

By April, Brigham Young agreed to give way to the new governor in exchange for peace. Governor Cumming arrived in Utah and was installed in office on April 12.

Brigham Young and other Church authorities declared that the Saints were never in rebellion. Given Buchanan’s failure to notify Young and the Army’s delayed arrival in Utah, many in the public began to perceive the Utah expedition as an expensive blunder, just as a financial panic had roiled the nation’s economy. Seeing a chance to end his embarrassment quickly, Buchanan sent a peace commission west with the offer of a pardon for destroying government property and interfering with military operations if Utah citizens would submit to federal laws. Young accepted the offer in June.

That month, Johnston marched unmolested through Echo Canyon into Salt Lake City and continued south for approximately 30 miles, establishing Camp Floyd, later renamed Camp Crittenden.

Echo Canyon, Utah, by the National Park Service.

With Cumming installed, the Army garrisoned in Cedar Valley, and economic and judicial aspects returned, the Utah War ended. It was the most prominent military operation between the Mexican-American War and the Civil War.

With the Army no longer a threat, the Mormons returned to their homes and began a long and fitful accommodation to secular rule under a series of non-Mormon governors.

Afterward, more Gentiles, including undesired camp followers, and thousands of soldiers entered and occupied Utah. Unwanted businesses, newspapers, drunkenness, and prostitution flourished, and additional federal officials, especially judges, were determined to indict and punish Mormons for crimes that included, most prominently, the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Mormon Zion was never the same. Through more federal involvement and laws, officials and others were determined to undermine Church control and power. Federal laws against polygamy targeted Mormon property and power through the 1870s and 1880s. Chilled relations between Latter-day Saints and outsiders, including passing emigrants, persisted for years.

This struggle lasted until Wilford Woodruff, the LDS Church’s fourth president, formally renounced plural marriage in 1890. He went further, saying that from now on, Mormons would obey the law of the land.” Statehood for Utah followed in 1896.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Porter Rockwell – Destroying Angel of Mormondom

Sources:

BYU Religious Studies Center

Issuu.com

National Park Service Publications

Smithsonian Magazine

Wikipedia