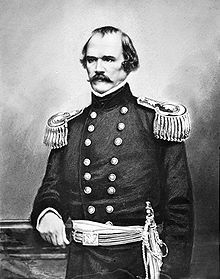

Albert Sidney Johnston was an American military officer who served as a general in three different armies — the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, fighting actions in the Black Hawk War, the Texas-Indian Wars, the Mexican-American War, the Utah War, and the Civil War, where he died on the battlefield.

Albert Johnston was born February 2, 1803, in Washington, Kentucky, the youngest son of Dr. John and Abigail Harris Johnston. A native of Salisbury, Connecticut, Albert’s father enjoyed a successful practice as one of the area’s few physicians.

After studying at private schools, Johnston entered Transylvania University at Lexington, Kentucky, at 15.

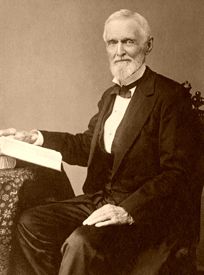

In 1821-22, Johnston altered his career path from medicine to the military and gained an appointment at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, where he befriended future Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Excelling in his studies, he graduated eighth in a class of 41 cadets in 1826 with a commission as a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry.

Johnston was assigned to New York and Missouri posts. In August 1827, he participated in the expedition to capture Red Bird, the rebellious Winnebago chief.

“I must confess that I consider Red Bird one of the noblest and most dignified men I ever saw…I have offended. I sacrifice myself to save my country.”

— Albert Sidney Johnston

In 1829, Johnston married Henrietta Preston, the sister of Kentucky politician and future Civil War general William Preston. They had three children, of whom two survived to adulthood. Their son, William Preston Johnston, became a colonel in the Confederate States Army.

Johnston served as chief of staff to Brevet Brigadier General Henry Atkinson during the brief Black Hawk War of 1832. The commander praised Johnston as ” a talent of the first order, a gallant soldier by profession and education, and a gentleman of high standing and integrity.”

Johnston resigned his commission in 1834 to care for his wife, who was dying of tuberculosis. She died two years later.

Johnston moved to Texas in 1836 following the outbreak of the Texas War for Independence and enlisted as a private in the Texian Army. On August 5, 1836, he was named Adjutant General and a Colonel in the Republic of Texas Army. On January 31, 1837, he became the senior brigadier general in command of the Texas Army.

On February 5, 1837, Johnston fought with Texas Brigadier General Felix Huston in a duel. Huston, who had been the acting commander of the Army, was angered and offended by Johnston’s promotion. He perceived Johnston’s appointment as a slight from the Texas government. Johnston was shot through the hip and severely wounded, requiring him to relinquish his post during his recovery.

On December 22, 1838, Mirabeau B. Lamar, the second president of the Republic of Texas, appointed Johnston Secretary of War. He defended the Texas border against Mexican attempts to recover the state in rebellion. In 1839, he campaigned against Native Americans in northern Texas during the Cherokee War of 1838–39. At the Battle of the Neches, Johnston, and Vice President David G. Burnet were cited in the commander’s report “for active exertions on the field” and “having behaved in such a manner as reflects great credit upon themselves.” In February 1840, he resigned and returned to Kentucky.

In 1843, he married Eliza Griffin, his late wife’s first cousin. The couple moved to Texas, where they settled on a large plantation in Brazoria County that Johnston named “China Grove.” Here, they raised Johnston’s two children from his first marriage and the first three children born to him and Eliza. A sixth child would be born later when the family lived in Los Angeles, California, where they had permanently settled.

When the United States declared war on Mexico in May 1846, Johnston rode 400 miles from his home in Galveston to Port Isabel to volunteer for service in Brigadier General Zachary Taylor’s Army of Occupation. Johnston was elected as colonel of the 1st Texas Rifle Volunteers. When the enlistments of his soldiers ran out just before the Army’s advance on Monterrey, Taylor appointed him as the inspector general of Brigadier General William O. Butler’s division of volunteers. Johnston convinced a few volunteers of his former regiment to stay on and fight.

During the Battle of Monterrey, Butler was wounded and carried to the rear, and Johnston assumed an active leadership role in the division. Future U.S. general Joseph Hooker was with Johnston at Monterrey and wrote:

“It was mainly through [Johnston’s] agency that our division was saved from a cruel slaughter… The coolness and magnificent presence [that he] displayed on this field left an impression on my mind that I will never forget.” General Taylor considered Johnston “the best soldier he had ever commanded.”

Johnston resigned from the Army just after the Battle of Monterrey in October 1846. He had promised his wife, Eliza, that he would only volunteer for six months’ service. He remained on his plantation until 12th President Zachary Taylor appointed him a major in the U.S. Army. In December 1849, he was made paymaster for a district of Texas encompassing the military posts from the upper Colorado River to the upper Trinity River. He served in that role for over five years, making six tours and traveling more than 4,000 miles annually on the Indian frontier of Texas. He served on the Texas frontier at Fort Mason and elsewhere in the western United States.

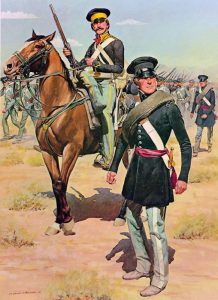

In 1855, President Franklin Pierce appointed him colonel and commanding officer of the new 2nd U.S. Cavalry, a new regiment he organized. Serving in this unit were several of Johnston’s future Civil War compatriots, including Robert E. Lee and William J. Hardee, as well as opponents — notably George Thomas.

On March 31, 1856, Johnston was promoted to temporary command of the entire Department of Texas. He campaigned aggressively against the Comanche, writing to his daughter that “the Indians harass our frontiers and the 2nd Cavalry and other troops thrash them wherever they catch them.” In March 1857, Brigadier General David E. Twiggs was appointed permanent department commander, and Johnston returned to his position as colonel of the 2nd Cavalry.

Johnston also led U.S. forces in a nearly bloodless campaign against the Mormons in the so-called Utah War of 1857–58. Johnston took command of the U.S. forces dispatched to crush the Latter Day Saint rebellion in November 1857. Their objective was to install Alfred Cumming as governor of the Utah Territory, replacing Brigham Young, and restore U.S. legal authority in the region.

Johnston worked tirelessly over the next few months to maintain the effectiveness of his Army in the harsh winter environment at Fort Bridger, Wyoming. Major Porter wrote to an associate: “Colonel Johnston has done everything to add to the efficiency of the command – and put it in a condition to sustain the dignity and honor of the country – More he cannot do… Don’t let anyone come here over Colonel Johnston – It would be much against the wishes and hopes of everyone here – who would gladly see him a Brigadier General.” Even the Mormons commended Johnston’s actions, with the Salt Lake City Deseret News reporting, “It takes a cool brain and good judgment to maintain a contented army and healthy camp through a stormy winter in the Wasatch Mountains.”

“Experienced on the Plains and of established reputation for energy, courage, and resources, [Johnston’s] presence restored confidence at all points and encouraged the weak-hearted and panic-stricken multitude. The long chain of wagons, kinked, tangled, and hard to move, uncoiled and went forward smoothly.”

— Major Fitz John Porter

Johnston and his troops hoped for war. They had learned of the Mountain Meadows Massacre and wanted revenge against the Mormons. However, a peaceful resolution was reached after the Army had endured the harsh winter at Fort Bridger. In late June 1858, Johnston led the Army through Salt Lake City without incident to establish Camp Floyd, some 50 miles distant. In a report to the War Department, Johnston stated that “horrible crimes… have been perpetrated in this territory, crimes of a magnitude and a studied refinement in atrocity, hardly to be conceived of, and which have gone unwhipped of justice.”

Johnston’s Army peacefully occupied the Utah Territory. U.S. Army Commander-in-Chief, Major General Winfield Scott, was delighted with Johnston’s performance during the campaign and recommended his promotion to brevet brigadier general: “Colonel Johnston is more than a good officer – he is a God send to the country thro’ the army.” The Senate confirmed Johnston’s promotion on March 24, 1858.

Concerning the relations established by Johnston with the Native American tribes of the area, Major Porter reported that “Colonel Johnston took every occasion to bring the Indians within knowledge and influence of the Army, and induced numerous chiefs to come to his camp… Colonel Johnston was ever kind but firm and dignified to them… The Ute, Paiute, Bannock, and other tribes visited Colonel Johnston, and all went away expressing themselves pleased, assuring him that so long as he remained, they would prove his friends, which the colonel told them would be best for them. Thus, he effectively destroyed all influence of the Mormons over them and ensured friendly treatment to travelers to and from California and Oregon.”

In late February 1860, Johnston received orders from the War Department recalling him to Washington, D.C., to prepare for a new assignment. He was there until December 21, when he sailed for California to take command of the Department of the Pacific.

When the Civil War broke out, he resigned his commission on April 10, 1861, but did not quit his post on the West Coast until his successor arrived. Like many regular army officers from the Southern United States, he opposed secession. However, he was a slave owner and a strong supporter of slavery. He had previously called abolitionism “fanatical, idolatrous, negro worshipping” in a letter to his son, fearing that the abolitionists would incite a slave revolt in the Southern states. The War Department accepted his resignation on May 6, 1861, effective May 3.

He then began the long trek to Richmond, Virginia, overland. Meeting with Confederate President Jefferson Davis, he entered Confederate service on August 30, 1861, as a full general and the second-ranking officer. Only Adjutant General and Inspector General Samuel Cooper ranked ahead of him.

He was given command of all Confederate troops west of the Allegheny Mountains, where he attempted to utilize isolated commands to hold points within the invaded Confederate states. Heading west, called on Arkansas, Tennessee, and Mississippi governors for new troops and established a line of defense in Kentucky from the Mississippi River to the Appalachians.

Johnston had fewer than 40,000 men spread throughout Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Missouri. Of these, 10,000 were in Missouri under Missouri State Guard Major General Sterling Price. Johnston did not quickly gain many recruits when he first requested them from the governors, but his more serious problem was lacking sufficient arms and ammunition for the troops he already had. As the Confederate government concentrated efforts on the units in the East, they gave Johnston small numbers of reinforcements and minimal amounts of arms and material. Johnston maintained his defense by conducting raids and other measures to make it appear he had larger forces than he did, a strategy that worked for several months.

A view of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia from Pinnacle Peak in Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Kathy Alexander.

On September 13, 1861, Johnston ordered Brigadier General Felix Zollicoffer with 4,000 men to occupy Cumberland Gap in Kentucky to block U.S. troops from entering eastern Tennessee. The Kentucky legislature voted to side with the United States after Polk’s occupation of Columbus. By September 18, Johnston had Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner with another 4,000 men blocking the railroad route to Tennessee at Bowling Green, Kentucky.

Johnston’s tactics annoyed and confused U.S. Brigadier General William Tecumseh Sherman in Kentucky, making him paranoid and mentally unstable. Sherman overestimated Johnston’s forces and was relieved by Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell on November 9, 1861. However, in his Memoirs, Sherman strongly rebutted this account.

Johnston held the area until it was broken at Mill Springs, Kentucky, in January 1862 and at Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862. Johnston was in a perilous situation after the fall of Fort Donelson and Henry; with barely 17,000 men to face an overwhelming concentration of Union forces, he hastily fled south into Mississippi by way of Nashville and northern Alabama.

Johnston’s Army of 17,000 men gave the Confederates a combined force of about 40,000 to 44,669 men at Corinth, Mississippi. On March 29, 1862, Johnston officially took command of this combined force, which continued to use the name of the Army of the Mississippi, under which General P.G.T. Beauregard had organized it on March 5.

In early April 1862, he moved against General Ulysses S. Grant’s army in Tennessee, surprising the Federals with an attack near Pittsburg Landing and driving them back in what would become the Battle of Shiloh. While directing front-line operations, Johnston was wounded in the leg, likely by friendly fire. Not realizing the seriousness of his wound, he sent his personal physician to attend to some captured Union soldiers, and he bled to death on April 6, 1862.

He was the highest-ranking officer of either side killed during the war, a decisive blow to the morale of the Confederacy. At the time, Davis considered him the best general in the country. Johnston was initially buried in New Orleans.

Johnston was survived by his wife, Eliza, and six children. His wife and five younger children chose to live at home in Los Angeles with Eliza’s brother, Dr. John Strother Griffin.

In 1866, a joint resolution of the Texas Legislature was passed to move his body to and reinter it at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin. The reinterment occurred in 1867.

Johnston was inducted into the Texas Military Hall of Honor in 1980.

By Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Also See:

War & Military Photo Galleries

Sources:

American Battlefield Trust

BYU Religious Studies Center

Encyclopedia Britannica

Wikipedia