On March 3, 1855, Congress appropriated $50,000 for surveying a road from Fort Riley, Kansas, to Bridger’s Pass in Wyoming. The survey intended to develop a better route from Fort Riley to Utah and California.

The first section was conducted from Fort Riley to Fort Kearny in Nebraska Territory. Lieutenant Francis T. Bryan, a topographical engineer, was in charge of this survey, accompanied by John Lambert, topographer; Harvey Engelmann, geologist; a survey crew; and a military escort. They started the survey from Fort Riley on June 21, 1856, proceeding up the east bank of the Republican River for 100 miles to the northwest through the present-day Riley, Clay, Cloud, and Republic Counties.

They crossed the prairie in a northwesterly direction toward Fort Kearny into Nebraska just east of Hardy. Then they went through present-day Nuckolls County and into Clay County, crossed the Little Blue River, and joined the Oregon/California Trail onto Fort Kearny. The group then went west to Bridger’s Pass, Wyoming, Utah, and California.

The survey team’s return route from Bridger’s Pass was south of their outward route until it reached a point of junction with their outward route near the present Kansas and Nebraska border. The outward route was chosen as the road to be established.

During the winter in St. Louis, Missouri, Bryan and his associates prepared a comprehensive report of their season’s work. The topographer made an elaborate road map with two draftsmen, including nearby topographical features. Lambert also reported on several side surveys made under instructions from the army engineer; Engelmann, the expedition’s geologist and mining engineer, summarized his observations in a technical paper. In time, these maps and reports were forwarded to the bureau in Washington, D.C.

Bryan reported to the War Department that given the limited funds remaining of the congressional appropriation, the route followed on the outward journey was the most advantageous. Running water was available the entire distance, and that portion of the road along the Platte River was already well established. The greatest obstacle was the lack of fuel. From Fort Kearny to Pine Bluffs, a distance of 300 miles, only buffalo chips were to be found. In Bryan’s opinion, this absence of timber, fuel, and shelter would always make traveling along the Platte River during the winter a hazardous and painful experience. However, the road between Fort Riley and Bridger’s Pass could be considered “practicable,” for 33 wagons had gone over it in 1856. The engineer’s only concern was that his road led into the heart of the mountains with no definite terminus.

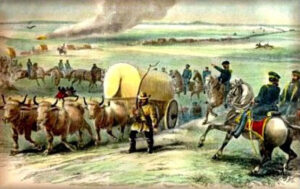

In the spring of 1857, Bryan organized a party of laborers to pass over his road again to remove obstacles and grade the banks of streams at crossings. Only with the assurance that an armed cavalry escort would be provided could the engineer find men willing to leave the settlements for several months on the assignment. The distance between Forts Riley and Kearny, measured at 193 miles, was traveled in 14 days and left in a “passable” state so that the farther portions of the road might be worked first. No improvements were deemed necessary between Fort Kearny and the Laramie Crossing, a road distance of 168 miles. When the Bryan party arrived at the Ford used the previous season, it was impassable due to high water. Still, four miles upstream, a satisfactory crossing was located at a camping ground of the Cheyenne Indians.

Along the route from the Platte River to the head of Lodgepole Creek, stream crossings were graded, and trees and stones were removed from the road in the timbered country at the creek’s headwaters. Crossings of the Laramie and Medicine Bow Rivers were improved. At several crossings of Sage Creek, small log bridges were constructed sufficient to pass a single wagon.

The laborers returned to Fort Kearny by September 1 and then turned their attention to improving the eastern section of the road. The banks were graded at the Little Blue River crossing, and the road opened through the timbered bottom. No bridge was deemed necessary because the stream was usually fordable, but many smaller streams between the Little Blue River and Fort Riley were deep and narrow and so difficult to cross that bridges were required. Bryan did not have the tools and mechanics to do the job, so they discharged the party and sold the animals and property belonging to the project to secure additional funds for the construction.

By March 1858, drawings and specifications for ten small bridges on the road immediately north of Fort Riley had been prepared, and a construction contract was given to Alfred Hebard for $12,500. The unexpended funds for the road only totaled $9,500, but Bryan assumed the expedition’s mules, wagons, harnesses, and other equipment would bring $3,000 at an auction. When this state of affairs was reported to the Secretary of War, Bryan was relieved of his command, and the Nebraska and Kansas roads were assigned to Captain Edward G. Beckwith.

On July 23, the public auction held at Fort Leavenworth was stopped by Beckwith’s order because no reasonable bids were being made by which a sufficient sum could be realized to cover the contract. Since the Secretary of War’s approval of Hebard’s contract was contingent upon raising $3,000 at the auction, Beckwith renegotiated the contract whereby Hebard would accept the balance of the funds for the road plus income from property sales, even if under $12,500, provided an extension of time from September 1 to December 1, 1858, was granted to complete the bridges. He was also permitted to use government mules for hauling supplies and construction work. The War Department approved this arrangement.

Alfred Hebard’s laborers used the timber growing on the Kansas streams to build several log bridges, but iron and flooring had to be hauled in to construct a half dozen frame bridges over the more significant creeks. The first grading proved a simple problem, but the contractor noted that it was not permanent, for once the sod was broken, the dirt washed out on the slightest grades. During September, Beckwith reported that the road was in good traveling condition, 50 miles above Fort Riley. The contractor was putting up the bridge at Parson’s Creek, which he hoped to complete during the first week of October, and, should the season prove favorable for work during November, all the bridges would be completed within contract time.

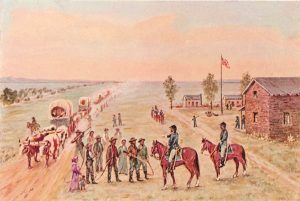

On November 20, the laborers arrived at Fort Kearny, completing all bridges except two small log structures. Returning immediately over the route, the contractor supervised improving approaches to bridges and the final constructions before the end of the month. Beckwith announced that the road was in excellent condition for the travel of the heaviest trains across the plains and hastened to Fort Leavenworth to report the close of the season’s operations on the road.

When complete, the road provided a more direct route from the Missouri River towns and Kansas forts. The new road reduced the distance to the Great Salt Lake by 100 miles. Bridger’s Pass was declared as easy and accessible as South Pass farther north.

The military road was active from the late 1850s through the 1860s. Afterward, travel by railroads became possible, and the use of this road diminished until it ended with the settlement of this region.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2025.

Also See:

The Range of the American West

Tales & Trails of the American Frontier

Trail Blazers, Riders, & Cowboys

Sources;

Jackson, W. Turrentine; The Army Engineers as Road Surveyors and Builders in Kansas and Nebraska, 1854-1858; Kansas State Historial Society, February 1949, Vol. 17, No. 1.

Scandia, Kansas Historical Marker