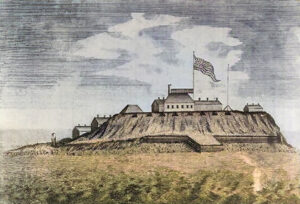

Castle Island and Boston Harbor, courtesy Wikipedia.

Fort Independence, formerly known as Castle William, sits on top of Castle Island in Boston, Massachusetts. Due to its strategic location on Boston Harbor, this site has been home to military fortifications for hundreds of years. It is considered the oldest fortified military site in British North America.

The first fort was constructed at this site in 1634 when Governor John Winthrop ordered the construction of a fort on Castle Island to provide harbor defenses for Boston. Construction was planned and supervised by Deputy Governor Roger Ludlow and Captain John Mason of Dorchester. They produced a primitive “castle with mud walls” with masonry of oyster shell lime in which three cannons were positioned to defend Boston from attack through the sea. The first fortification was called “The Castle,” commanded by Captain Nicholas Simpkins.

The first fort soon fell into disrepair and was rebuilt in 1644 following a scare due to the arrival of a French warship in the harbor. The French arrived seeking aid against fellow Frenchmen in a dispute over trading rights in Nova Scotia. As no salute came to the visiting ship from the Fort, the Massachusetts Militia authorities decided to upgrade the fort. The fort was reconstructed out of pine logs, stone, and earth, with ten-foot walls around a 50-foot square compound. It mounted six saker cannons and three smaller guns. The saker guns, a top-of-the-line cannon at the time, with a range of over a mile, could fire five to six-pound balls.

The fort was destroyed by an accidental fire on March 21, 1673. The following year, it was rebuilt in stone, with 38 guns and 16 long cannons in the four-bastion main fort and six guns in a water battery. The cannons had an effective range of 1,800 feet and were valued for their range, accuracy, and effectiveness. Governor Edmund Andros was confined in the fort and sent to England to stand trial in 1689, following the Glorious Revolution in England, in which King William III replaced King James II.

In 1689, British Governor Edmund Andros fled to Castle Island after King James II was overthrown in England. Edmund Andros attempted to streamline the authorities in New England by bringing them more under the king’s control. One of the acts he tried to enforce was the Navigation Act, which prohibited U.S. foreign ships from landing in England and banned the colonies from exporting certain products to any other country except England.

In 1692, a more substantial structure was built called Castle William, named after King William II of England. The new work had 54 cannons: 24 nine-pounders, 12 24-pounders, and 18 32- and 48-pounders.

In 1701, Wolfgang William Romer, the Chief Engineer of British forces in the American colonies, designed a new fort, increasing its armament to over 100 guns. He also added a complex system of outer defenses outside the Fort, requiring the enemy to cross three sets of fortifications to enter the Fort — the waterfront, the secondary, and the Fort itself. A new lookout tower at the northeast corner of the Fort that surveyed the outer harbor was added. The Fort was called Castle William after King William II of England.

In 1740, a fifth bastion was added, mounting 20 42-pounders.

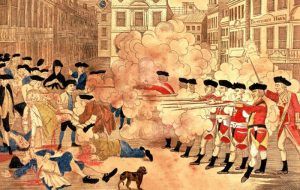

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, Castle William became a refuge for British officials during unrest and rioting in Boston. Violence forced provincial leaders and British soldiers to take shelter within the fort in the wake of events such as the Stamp Act crisis in 1765 and the Boston Massacre in 1770.

Castle William’s role shifted from protecting against potential attacks from European powers to providing a refuge for British soldiers facing colonial upheaval in Boston. After the Boston Massacre in 1770, Bostonians called for British troops stationed in the city to be removed to Castle William. British forces maintained their presence at Castle William for the next six years.

As the American Revolution erupted in 1775, American forces quickly commenced the Siege of Boston, and British forces made Castle William their primary stronghold. It was not until the Continental Army led by General George Washington managed the fortification of Dorchester Heights that Castle William was threatened, and the British evacuated Boston in March 1776. Before leaving Castle William, the British set fire to the fort.

At the beginning of March 1776, the Continental Army fortified nearby Dorchester Heights in the dead of night using cannons they had taken from Fort Ticonderoga, New York. The following morning, British Commander General Howe attempted an attack using row boats on Dorchester Heights but had to turn back due to a snowstorm. Now surrounded, Howe decided to remove his 10,000 troops and 1,000 loyalists from Boston.

Commander Howe and American General George Washington had reached a tacit agreement. So long as the British could leave unmolested, they would not destroy downtown Boston. After some British soldiers started some “plundering” in downtown Boston, Howe issued the following proclamation:

“The commander-in-chief, finding, notwithstanding former orders that have been given to forbid plundering, houses have been forced open and robbed, he is therefore under a necessity of declaring to the troops that the first soldier who is caught plundering will be hanged on the spot.”

Howe burned down the fort and destroyed its weaponry and ammunition as part of his “gentleman’s agreement” evacuation with Washington.

After the smoke cleared, Continental forces quickly rebuilt the fortifications at Castle William into a star-shaped fort and renamed it Fort Adams. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Revere led the troops stationed here.

In 1785, the legislature of Massachusetts designated the fort as a prison, in which capacity it served until 1805.

In the late 1790s, the federal government took command of the fort, repairing and expanding it. In 1797, the name was transferred to the former Castle William, leaving the fort in Hull without a name. The fort was renamed Fort Independence during a ceremony attended by President John Adams in 1799. The following year, the fortification of the island was turned over to the United States government.

The fort was rebuilt and expanded in 1800-1803 under the first system of U.S. fortifications. The Secretary of War’s report on fortifications for December 1811 described the fort as “…a regular pentagon, with bastions of masonry, mounting 42 heavy cannon, with two batteries for six guns…” The plan was to provide a five-star Fort with a detached external battery overlooking the harbor entrance.

The fort was repaired and expanded during the War of 1812. During this time, the British Navy ran a blockade around Massachusetts, constantly hovering around the coast and threatening to destroy the state’s coastal towns. A British Navy squadron repeatedly captured American merchant and fishing vessels in Massachusetts Bay. However, due to Fort Independence’s strength, they never attempted an attack on the Boston port. Colonel John Beck was the Fort’s commandant during the War of 1812. After the war, it fell into disuse.

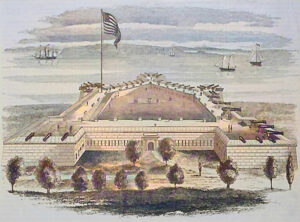

The existing granite bastion fort was constructed between 1833 and 1851. Built under the third system of U.S. fortifications, it was supervised by Colonel Sylvanus Thayer, one of the nation’s leading military engineers. The Fort was made of granite from Rockport, Massachusetts, with walls 30 feet high and 5.5 feet thick. It was mostly complete by 1848, although repairs and other work continued until 1862.

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, Fort Independence was garrisoned by the Fourth Battalion of Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. The battalion set the fort in order and was trained in infantry and artillery drills, eventually forming the nucleus of the 24th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. At the height of its strength during the Civil War, it mounted 96 cannons, some of which were 15-inch Rodman guns capable of firing a 450-pound shot more than three miles. A small part of Castle William’s brick structure remains in the rear portion of the present fort, but is covered up by subsequent stonework.

Following the Civil War, Fort Independence gradually ceased use, and the larger Fort Warren reduced its importance.

In 1890, the Federal government ceded Castle Island, excluding the fort, to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The city began filling the marshes separating Castle Island from South Boston to create green space and promenades.

The Federal government briefly reclaimed Castle Island in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, but it was quickly returned to Boston in 1899.

The Federal government ceded the fort to the city of Boston in 1908.

The military again took control of Fort Independence during World War I in case of a coastal attack. During this time, the fort was used primarily as a depot for small arms ammunition.

As Boston continued filling the marshes, Castle Island ceased to be an island by the 1920s.

The military again took control of Fort Independence during World War II, and anti-aircraft guns were added. At that time, the Navy used it as a demagnetizing station for ship hulls.

In 1959, the Metropolitan District Commission began constructing a walkway with an opening to control incoming and outgoing tides that now formed in Pleasure Bay. This walkway extends over two miles and has provided a delightful walk ever since.

In 1962, the federal government permanently deeded Castle Island and Fort Independence to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, U.S. Etts. They are now overseen by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation and the non-profit Castle Island Association. Throughout its history, Fort Independence has never fired a shot in anger.

Fort Independence was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

Today, Fort Independence is part of a state park on Castle Island. During warmer months, the Castle Island Association, in partnership with the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, provides free tours and occasionally fires ceremonial salutes.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Fort Independence

National Park Service

Wikipedia

Fort Independence, Boston, Massachusetts, courtesy of Wikipedia.