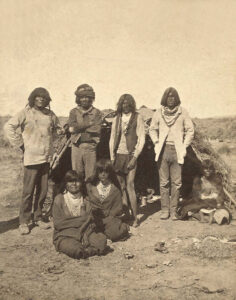

The Maricopa or Piipaash are a Native American tribe traditionally living on or near the Gila River in southern Arizona. Today, they primarily live in the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community and the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona, along with the Pima, a tribe with whom the Maricopa has long held a positive relationship.

The Maricopa people consist of three historically distinct but later incorporated cultural groups: the Halchidhoma, Halyikwamai, and Kohuana. Their language is classified as part of the Yuman group within the Yuman-Cochimí language family. Together with the closely related Yuma and Mojave languages, Maricopa falls under the River branch of the Yuman language group.

The neighboring Pima people called the Maricopa the Kokmalik’op, which means “enemies in the big mountains.” The Spanish transliterated this to Maricopa. The Maricopa people call their group Piipaa, Piipaash, or Pee-Posh, all meaning “people.”

Historically, the Maricopa consisted of small groups of people who lived for generations along the banks of the Colorado River. In the 16th century, they were driven eastward from the lower Colorado River to the area around the Gila River to escape attacks from the Yuma and Mojave tribes.

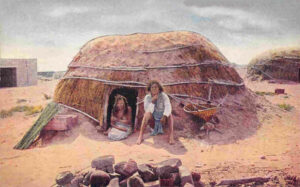

Traditionally, the Maricopa resided in clusters of villages, with each house belonging to a few related families. Their earth houses featured a flattened dome supported by a rectangular frame across four upright pillars. The roofs and walls were packed with sandy soil.

In addition to their homes, the Maricopa constructed several other structures, including semi-subterranean granaries and circular ceremonial huts. Their ceremonial architecture included larger meeting houses, small sweathouses, and women’s shelters used during childbirth and the first menstruation rituals.

Village sites frequently changed due to the practice of burning a house and the belongings of a deceased household head after the cremation of their body. In addition to relocating surviving family members, Maricopa customs required the sacrifice of a horse to allow the deceased to ride westward into the afterlife.

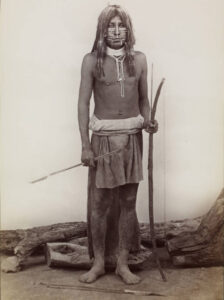

The traditional Maricopa economy was based on hunting and gathering, supplemented by intensive agriculture. Men and women worked together in farming. Women collected seed-bearing pods from mesquite trees and gathered nuts and berries, while men hunted or fished nearby, ready to protect the women.

The Maricopa traded crafts and goods among themselves and neighboring groups, often bartering horses acquired through inter-group raids.

The basic building blocks of traditional Maricopa society were family groups or bands, which identified themselves by their area of origin. Each band formed a residential community led by a headman called “pipa-stay,” meaning “big man.” The village headman commanded respect due to his maturity and experience. His responsibilities included organizing defense and raids, supervising public works, and arbitrating disputes. In most cases, the headman was also a clan chief, with the position sometimes inherited through the male line.

While descent was primarily traced through male ancestors, female links were important in establishing relationships. Patrilineal clans functioned as corporate groups that regulated marriages, sponsored ceremonies, and organized ritual feasts.

Maricopa clans traditionally married only outside their clan or tribe. Family genealogies reflected patterns of serial marriage for both men and women, indicating that marriages and divorces were common. Polygyny, particularly of the sororal type, was permitted. Child training focused on the informal learning of adult family tasks. Boys and girls were encouraged to endure pain as a vital personal virtue and a valuable life skill.

Traditional Maricopa crafts included highly burnished red-on-red pottery, basket making, weaving textiles, and various wooden and stone tools and utensils. Women primarily made pottery, while both men and women engaged in weaving. Maricopa artists also included storytellers and singers, who claimed their unique talents were revealed through dreams, indicating a direct connection between Maricopa art and religion.

The Maricopa people believed in various spirits that guided individuals to special abilities by revealing themselves through dreams. They stated, “Everyone prosperous or successful must have dreamed of something.” These abilities included healing, bewitching, foretelling the future, singing ritual songs, and conceiving children.

Common illnesses were often attributed to “bad dreams.” Curers, who possessed special powers revealed in dreams, utilized intense heat—typically in sweat lodges and meeting houses—believing it cleansed the mind while healing physical ailments.

The Maricopa recognized several traditional religious practitioners who collectively provided direction and support to those in need. This group included prophets, curers, calendar-stick keepers, and potters. They also acknowledged ceremonial specialists who constructed funeral pyres, led dances and sang at public events.

One significant Maricopa ceremony involved a public dance held in honor of a young woman following her first menstrual seclusion. This ceremony also included tattooing the girl’s face, a practice that reportedly continued among some families well into the 1970s.

Migration stories of the Maricopa describe territorial wars and raids against culturally and linguistically related groups, such as the Mojave and Yuma. Other adversaries included the Yavapai and Apache. Droughts and food shortages were significant causes of conflict in the region.

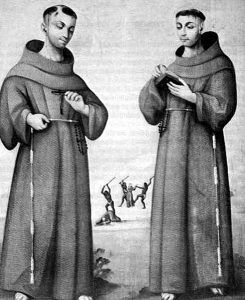

In 1770, Spanish priest Francisco Garces encountered the Maricopa and noted they had “good lands” where they grew cotton, squash, watermelons, maize, and wheat in the first rancherías. He described the people as “robust and stocky, comparatively light-skinned, and seemingly hard workers.”

By 1775, Garces reported that Maricopa rancherías extended about 40 miles along the Gila River, from the mouth of the Hassayampa River to Aguas Calientes. He noted, “Some of them are found farther downriver” and estimated their population to be around 3,000.

Both local traditions and scholarly accounts suggest that the Maricopa migrated from the Colorado River to the lower Gila Valley area. The first to move was a Pi-Posh chief who settled his people along the south side of the Estrella Mountain Range in 1825. That same year, a group of American trappers, including James Ohio Pattie, massacred 200 Maricopa in retaliation for an earlier attack.

In 1830, the Halchidhoma chief led his people to seek protection from attacks by the Mojave and Yuma tribes, feeling that they would be defenseless without the support of the Pi-Posh. In 1838, elements from the Kohuana and Halyikwamai communities joined them.

Throughout the 1840s, the tribe suffered from epidemics of new infectious diseases, significantly impacting their population. By the mid-1800s, their number had likely fallen to fewer than 700 individuals. During the 19th century, the Maricopa formed a confederation with the Pima tribes.

In the 1850s, the United States began taking control of the area, and the Gadsden Purchase of 1854 officially incorporated southern Arizona as part of a United States Territory. In 1857, the Maricopa and Pima triumphed over the Yuma and Mojave tribes at the Battle of Pima Butte near Maricopa Wells. Following this defeat, the Yuma ceased to venture further up the Gila River.

On February 28, 1859, the Gila River Indian Reservation was established for the Maricopa and Pima along the Gila River in Arizona. This was the state’s first reservation, covering 372,000 acres. Reports indicate that hostilities between tribes diminished in the 1860s as the United States government established effective control over the region.

The Maricopa became successful farmers, producing three million pounds of wheat in 1870. However, later droughts and water diversion by non-Indians resulted in widespread crop failures. On August 31, 1876, an executive order expanded the Gila River Indian Reservation. The Salt River Reservation was added in 1879, and subsequent executive orders on May 5, 1882, and November 15, 1883, further enlarged the Gila River Indian Reservation. However, no treaty was ever established with the Maricopa.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the Bureau of Indian Affairs implemented policies to assimilate the Maricopa into mainstream European-American society, including introducing Presbyterian missionaries into their communities.

In 1905, 350 students were enrolled under the direction of the Pima school superintendent in Arizona. By the 1910 census, the population of Maricopa on the Gila River Reservation had increased to 386, with little change observed through the middle of the century.

In 1914, the U.S. Government divided communal tribal landholdings into individual allotments to encourage subsistence farming. However, this approach was unsuitable for the area’s geography and climate.

In 1926, the Bureau of Indian Affairs established the Pima Advisory Council to represent the Pima and Maricopa communities. Following the congressional passage of the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934 and 1936, the Pima and Maricopa agreed on a constitution restoring self-governance to their tribes.

The current tribal government consists of a 17-member council, which is popularly elected and governed by a constitution adopted per the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

Throughout the 1930s, the Gila River’s surface flow diminished to nothing, causing significant hardship for the tribe due to losing their water source. Unfortunately, the Bureau of Indian Affairs neglected the tribe’s water issues. Consequently, the tribe resorted to using brackish well water, insufficient for growing edible crops. As a result, they began cultivating cotton as a cash crop.

From 1937 to 1940, there was a revival of traditional pottery practices. Elizabeth Hart, a U.S. Home Extension Agent, collaborated with a prominent Maricopa potter, Ida Redbird, to establish the Maricopa Pottery Cooperative. Redbird served as the cooperative’s president, including 17 to 19 master potters. Hart encouraged the members to sign their work. The swastika, a common traditional motif, was abandoned in the 1940s due to the Nazi appropriation of the symbol.

By 1977, 607 people lived in the predominantly Maricopa reservation area. Since the mid-1980s, the Maricopa have primarily relied on income from leasing agricultural land and business properties. They have also supplemented their income by growing maize, beans, pumpkins, and cotton.

The 1990 national census recorded 744 Maricopa nationwide, with 710 residing in Arizona. A 1997 estimate indicated that the number of ethnic Maricopa was around 400, with 160 individuals still retaining the language.

The 2000 census counted 255 Maricopa among a total of 7,295 Yuman nationally. Proportionally, there may have been 270 Maricopa out of the 7,727 Yumans based on a preliminary report from the 2010 census.

Today, most Maricopa people live alongside members of the Pima tribe on and near the Gila River and Salt River Indian Reservations in Arizona.

The Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community is a sovereign tribe in the metropolitan Phoenix area. Bounded by the cities of Scottsdale, Tempe, Mesa, and Fountain Hills, the community encompasses 52,600 acres, with 19,000 held as a natural preserve. The majestic Red Mountain can be seen throughout the community and is located on the eastern boundary. The mountain symbolizes the home of the Pima and Maricopa people.

Although the community derives from two distinct cultures and languages, the two tribes have been allies for generations and share many of the same values. Although each tribe formerly recognized its leaders and independently managed its day-to-day affairs, they interacted regularly. Intertribal commerce, decision-making, military action, and social interaction are common. The community is a full-service government that oversees departments, programs, projects, and facilities.

Visitors are invited to the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community’s Hoo-Hoogam Ki Museum, where baskets, pottery, and artifacts from many tribes are displayed. Casino Arizona is one of several enterprises owned and operated by the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. There are two Casino Arizona locations in neighboring Scottsdale.

More Information:

Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community

10005 E. Osborn Rd.

Scottsdale, AZ 85256

480-362-7400

The Gila River Indian Community is an Indian reservation in the U.S. state of Arizona, lying adjacent to the south side of the cities of Chandler and Phoenix, within the Phoenix Metropolitan Area in Pinal and Maricopa counties. The community was established in 1859 and formally established by Congress in 1939. It is home to members of both the Pima and the Maricopa tribes.

The reservation has a land area of 583.75 square miles and a 2020 Census population of 14,260. It comprises seven districts along the Gila River, and its largest communities are Sacaton, Komatke, Santan, and Blackwater. Tribal administrative offices and departments are located in Sacaton. The community operates its telecom company, electric utility, industrial park, and healthcare clinic and publishes a monthly newspaper.

Under its constitution, tribal members elect a governor and lieutenant governor. They also elect 16 council members from single-member districts or sub-districts with roughly equal populations.

The Gila River Indian Community is approximately 34 miles south of the Sky Harbor International Airport in Phoenix, Arizona.

More Information:

Gila River Indian Community

525 West Gu U Ki, P.O. Box 97

Sacaton, AZ 85147

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2025.

Also See:

Arizona – The Grand Canyon State

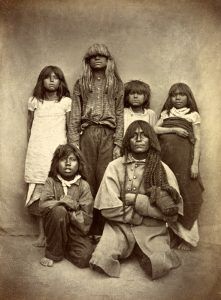

Native American Photo Galleries

Sources:

eHRAF World Cultures

Hodge, Frederick Webb; The Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico; Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office. 1906.

Intertribal Council of Arizona

Salt River Pima–Maricopa Indian Community

Wikipedia