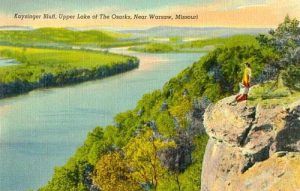

Warsaw, Missouri, the County Seat of Benton County, is a small town of some 2,200 permanent residents, which just about doubles during the lake season as fishermen, campers, and lake enthusiasts move down to their seasonal homes or just come for the area opportunities. Warsaw is located between two of Missouri’s largest lakes — Truman Reservoir and Lake of the Ozarks.

Rich in history, from Native Americans to steamboats to Civil War skirmishes, Warsaw has endured throughout the years to become a quickly growing community that exudes small-town charm and provides numerous recreation opportunities for locals and visitors alike.

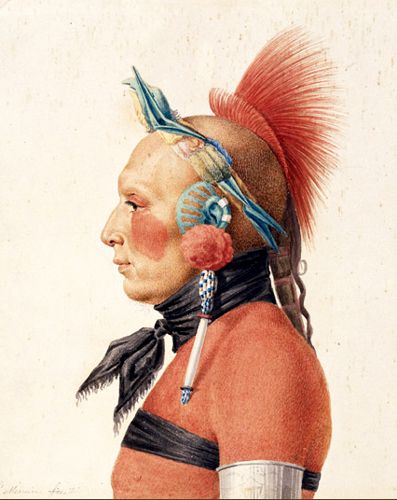

Osage Warrior.

When white explorers came to the area in 1719, several Indian tribes called the region home, including the Delaware, Shawnee, Kickapoo, and Sac and Fox. By far, however, the land was occupied by the Osage Indians, from which the river would later take its name. With its plentiful supply of rivers and springs, the area abounded with game, providing superb hunting grounds for the Indians. In its bluffs and hills, the Indians found abundant amounts of flint rock in order to make arrows, knives, and other weapons.

Early French hunters, trappers, and traders soon began to trade with the Indians along the Osage River, which increased significantly by the early 1800s as white settlers saw opportunities on the river itself.

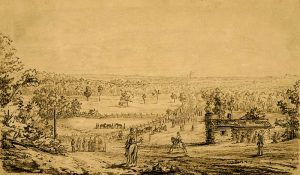

The area that would become the town of Warsaw was first settled around 1820, primarily by Kentucky and Tennessee farmers of English, Irish, and German descent. Early on, the settlement became a crossroads of travel and freight. The first ferry was established on the Osage River in 1831 by Lewis Bledsoe, where the site of Bledsoe Ferry Park, near Truman Dam, is today. Bledsoe’s Osage Ferry served the Boonville-Springfield Road, parts of which were also called the Old Military Road or Wire Road, east of town. Mark Fristoe later established another ferry to the west. Soon, numerous freight wagons, stagecoaches, and wagon trains began to pass through the area.

One of the earliest residents of Benton County was Stephen A. Howser from Kentucky. He and his wife, Sarah (Sally) Wyatt Howser, settled in the area that would soon become Warsaw around 1831. Later, they would deed part of their land on the Osage River for the new township. Alas, they would also be the parents of a boy who would later make his name known in Missouri’s darker annals of history as a murderer and a thief.

Benton County was first created in January 1835, from parts of Pettis and Greene Counties, and named for Thomas Hart Benton, a United States Senator from Missouri.

The county “offices” were initially held in a home near Bledsoe’s Ferry, which was doing a brisk business. In 1836, the Gazetteer of Missouri described the new “town,” which was then referred to as “Osage” or “New Town,” in promising terms, including plans for a great hotel, mills, warehouses, and merchants, and predicting a population of several thousand over the next five years.

Town lots for Warsaw were first sold in February 1838, and the town slowly grew. The first Benton County Court met in various homes in the area, but a new site was soon chosen at the corner of Washington and Van Buren Streets (where the county jail now stands). Through lot sales, money was raised for a new “temporary” courthouse building, and a 20-foot by 30-foot log building was constructed. Two years later, construction on a permanent two-story courthouse began. The new structure cost $4,500, and county officials began occupying the building in 1842. The following year, the City of Warsaw was officially incorporated.

Reser’s Funeral Home was once the site of the Nicholas Tavern, later called the Farmers Hotel and Newman’s Hotel, by Kathy Alexander.

Though most accepted that “Osage” would be Benton County’s new county seat, nearby Fristoe and other small trading centers fought for the County Seat designation, delaying the selection for two years. Finally, Warsaw was made the official county seat in 1843. Though there is no written record of how the town’s name was chosen, it is believed that it was named after Poland’s capital city in honor of Polish General and Patriot Tadeusz Kosciusko. Adamson Cornwall was both the first merchant and postmaster.

That same year, the first steamboats traveled the Osage River, docking in Warsaw, carrying cargos of salt, iron, nails, and other supplies to the area. On their return voyage, the steamboats hauled meat, furs, grain, eggs, and whiskey. Because of the shoals and tight bends in the river, the steamboats were necessarily smaller and had shallower drafts than those operating on the Missouri River. But they did travel and trade, transferring goods from St. Louis and back.

Historic Marker, Warsaw, Missouri, by Kathy Alexander.

Today, at the site where Reser’s Funeral Home is located, was the Nicholas Tavern, later called the Farmers Hotel and Newman’s Hotel. The original building, built in the 1840s, would later serve as a daily mail and stage stop for the Butterfield Stage Line from 1858 to 1861. Reser’s current building incorporates part of that early structure.

In 1840, an old-fashioned Hatfield & McCoy style feud occurred in Benton and Polk Counties (an area where Hickory County would later be formed). The feud was between the Hiram Turk family, who owned a store and saloon south of Warsaw, and the Andy Jones Family, who lived along the Pomme de Terre River. The Jones family, who evidently had a penchant for such habits as horse racing, gambling, and counterfeiting, were not liked by the Turks, who, though well-educated, were known to never back down from a fight.

The whole affair began on Election Day, 1840, when Turk’s Store was established as a local polling place. Andy Jones and one of Hiram Turk’s sons, Jim, got into a dispute there. Before it was over, members of both families were involved in the fray. In the end, the Turks were charged with assault and starting a riot. Over the next several years, the feud would expand, both inside and outside of the courts, resulting in several killings and dubbed the “Slicker War.”

In 1857, the Mechanics Bank of St Louis was established at Washington and Van Buren Streets. It was considered the most expensive bank building in western Missouri. However, it closed just four years later when Warsaw was devastated by General Fremont’s troops in 1861. It stood empty until 1912, when the Benton County court bought it and converted it into a jail, which was used until early 2021.

Riverboat traffic remained brisk during the 1850s, with as many as seven steamboats at the Warsaw wharf at any given time. However, when the Civil War broke out, guerrilla terrorism on the Osage River stopped local trade.

At about the same time that the Civil War was declared in 1861, Benton County had another worry on their hands – that of accused murderer Stephen Howser, son of one of the area’s earliest settlers, Stephen A. Howser. More commonly called Hough, the younger man was accused of killing a man named Halloway while on his way to California, as well as a Gasconade County man named Farris in 1859. Though Howser had been sentenced to prison by a St. Louis Court in 1859, for whatever reason, the killer was pardoned in 1861 and began to make his way back to Warsaw. Along the way, he was said to have killed a man in Baldwin, Missouri. Soon after his return to Warsaw, he shot and killed a man named D.D. Jones, allegedly after robbing him. He fled the city but was diligently tracked by Benton County lawmen. He was soon overtaken and killed in Vernon County, Missouri.

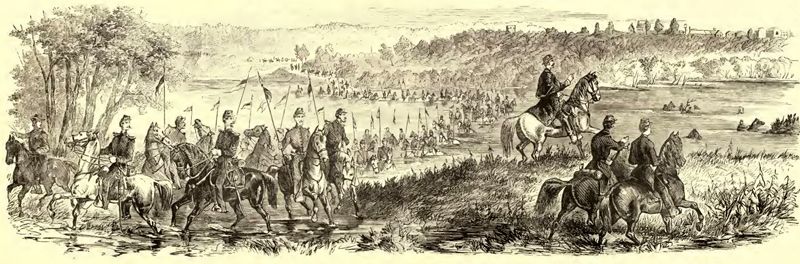

Fording of the Osage River at Warsaw, by General Fremont, October 1861. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil War, 1895.

Violence would continue in the county as Missouri was enmeshed in the Civil War. Despite being actively a slave-holding state, Missouri would not secede from the Union, creating a great deal of conflict within its borders. On April 23, 1861, a crowd of citizens raised a rebel flag on the east side of the courthouse lawn. However, two months later, the State of Missouri joined the conflict on the side of the Union.

Quickly, a regiment of Union soldiers called the Benton County, Missouri Home Guards was established on June 1861. Made up of several Missourians of primarily German descent, they would see combat just six days later at the Battle of Cole Camp. The battle resulted in a Confederate victory, with some 34 Union soldiers killed, another 60 wounded, and 25 taken prisoner. The Benton County Home Guards officially lasted for only 90 days, after which its members either returned home or joined other regiments.

But for Warsaw, the worst was yet to come. From October 17-21, 1861, Union General John C. Fremont’s troops, perceiving Warsaw as a “treasonous” city, fairly devastated the town, taking over its supplies and homes for their own needs. The next month, on November 22, Union Army stragglers followed Fremont’s troops; they burned much of what had not already been destroyed.

On February 13, 1862, Major Ed Price, son of Confederate General Sterling Price, was captured. A few months later, in April, there were several nearby skirmishes, as well as more fighting in Warsaw that October. Before the war was over, what was left of the town would be burned again on November 7-9, 1863, by Confederate Colonel Shelby’s troops as they marched through the town on their way to Cole Camp.

War-torn and bitter, Warsaw residents would survive and rebuild. Navigation and trading on the Osage River returned, and merchants began to prosper once again.

In 1874, Warsaw reported a population of about 500, two churches, a hotel, a school, a bank, 15 retail establishments, two newspapers, a flour mill, and a sawmill.

The first train arrived in Warsaw from Sedalia in November 1880, which ceased the need for riverboat traffic on the Osage River. The Homer C. Wright was the last steamer to work on the Osage River. After its years of usefulness were over, it eventually sank during a winter ice storm.

In 1881, the Benton County Courthouse was found to have severe foundation problems and was ordered condemned. Plans for a third and final courthouse were made, but it wouldn’t be completed until 1886.

That next year, a railroad disaster took place on November 2897, when a narrow-gauge train plunged off its trestle 2 ½ miles northeast of Warsaw, killing engineer John Minnier.

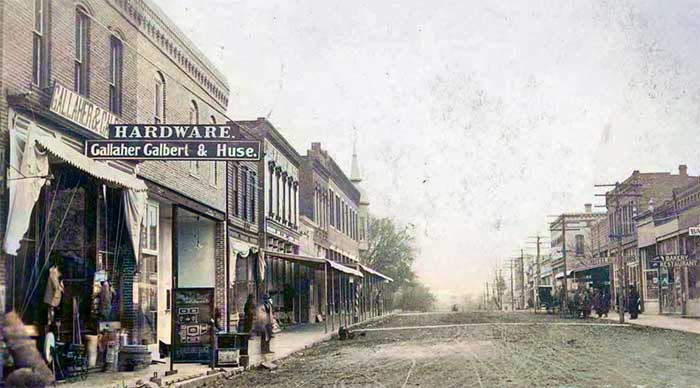

Warsaw, Missouri main street 1911. Touch of color by LOA.

By the turn of the century, automobiles quickly replaced horses and buggies, and new bridges were needed.

The first suspension bridge in the Lake Area was built in Warsaw in 1895, devised and financed by D.M. Eddy, a Warsaw physician interested in bridge design. A toll was charged to cross the bridge to offset the financing costs. Eddy’s construction foreman was Joe Dice, also of Warsaw. Dice and another bridge contractor named Charles Bibb would build the vast majority of the Ozark River bridges in the early 1900s. Called the Drake Bridge, and later referred to as the “Middle Bridge,” the toll was lifted in 1904 when money was raised to turn it over to the county.

Over the years, the bridge suffered several tragedies, beginning with a collapse in March 1913 under the weight of a stampeding cattle herd. A replacement suspension bridge was built in 1927, but it was condemned due to flooding in 1936. It was repaired and reopened in 1943, only to close once again in 1955, also due to flooding. Condemned once again, the bridge stood silent until 1975, when it was demolished.

Another suspension bridge, the Hackberry Bridge or the Lower Bridge, was built in Warsaw just two years after the first one. It was destroyed by fire in 1926 and never rebuilt.

A third bridge was also built in 1904 for $5,500. When it opened, it too was a toll bridge. However, in June 1924, it was destroyed by a tornado. A replacement bridge was then built in 1927 by Joe Dice, the same foreman who had helped construct Warsaw’s first bridge. Referred to as the Upper Bridge, the 600-foot pathway across the river continued to serve automotive traffic until 1979, when it was closed to vehicles. Today, renamed “The Joe Dice Swinging Bridge,” it is the last of 15 swinging bridges that once crossed the Osage River. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the bridge now serves pedestrians.

In August 1929, construction on the Lake of the Ozarks began, impounding the Osage River and smaller tributaries, including the Niangua River, Grandglaize Creek, and Gravois Creek. The Union Electric Company of St. Louis, Missouri, constructed the 2,543-foot-long Bagnell Dam.

Two years later, the dam was completed in April 1931. The lake that formed was at first referred to as Osage Reservoir or Lake Osage, but everyone always called it the Lake of the Ozarks. At the time of construction, it was one of the largest man-made lakes in the world and the largest in the United States. It quickly became a major Missouri tourist destination. Today, it has a surface area of some 55,000 acres, over 1,150 miles of shoreline, and its main channel stretches 92 miles from end to end. Unlike flood-control lakes constructed by the Corps of Engineers, most of the shoreline is privately owned.

Located at the headwaters of the Lake of the Ozarks, the Warsaw area began to develop resorts and businesses along the shoreline of the channel. Warsaw, as a resort destination, increased when the Harry S. Truman Dam and Reservoir were completed in 1979. Developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the lake’s primary mission is flood control, but it also serves power generation, recreation, and wildlife management.

Today, cabins and homes dot the roads and lakeshores around Warsaw for miles, and visitors and locals enjoy sitting in the very center of two of Missouri’s largest lakes. Warsaw has become a popular retirement community and tourist destination, as visitors enjoy water sports, fishing, camping, and antique shopping in its quaint downtown district.

More Information:

City of Warsaw

181 W. Harrison

PO Box 68

Warsaw, Missouri 65355

660-438-5522

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2025..

Also See:

The Slicker War of Benton County

Note: Warsaw, Missouri, is Legends of America’s official home and headquarters. We relocated from the Kansas City area in June 2010 and have expanded our part-time cabin into a full-time home and office by adding a garage and an additional cabin. We love our new home in Warsaw, Missouri.

Views taken from around our home are available in our “Sitting on the Dock at the Lake” Photo gallery.