Nat Turner’s Rebellion, historically known as the Southampton Insurrection, was a four-day slave rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831. Led by Nat Turner, an enslaved Black carpenter and preacher, the rebels, made up of enslaved and free African Americans, killed between 55 and 65 White people, making it the deadliest slave revolt in U.S. history. The rebellion was effectively suppressed within a few days at Belmont Plantation on the morning of August 23, but Turner survived in hiding for more than 30 days afterward.

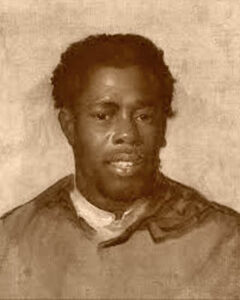

Turner was born as a slave of Benjamin Turner on October 2, 1800, on a prosperous small plantation in Southampton County, Virginia. At that time, the county was a rural plantation area with more Black people than White. His mother was an enslaved woman named Nancy, but little is known of his father, who was believed to have escaped from slavery when Nat was a child. His mother transmitted a passionate hatred of slavery to her son, and Nat grew up very attached to his grandmother.

He learned to read and write from one of his master’s sons and was instructed in religious matters. As a result, he became devoutly religious, spending his free time reading the Bible, praying, and fasting.

Benjamin Turner died in 1810, and his son Samuel inherited Nat.

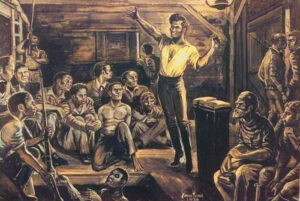

Virginia Plantation by Junius Stearns, 1853.

In 1821, Turner ran away and hid in the woods for a month before becoming delirious from hunger and receiving a vision that told him to “return to the service of my earthly master.”

Turner married an enslaved woman named Cherry, and the couple would eventually have three children — Gilbert, Riddick, and Charlot.

When Samuel died in 1823, Turner was sold to Thomas Moore, and his family was sold to Giles Reese.

Turner received a vision in 1825 of an impending bloody conflict between blacks and whites.

Sometime later, Thomas Moore died, and his widow married John Travis, who sent Turner to work on his land. Turner later said Travis was “a kind master” who “placed the greatest confidence” in him.

During these years, Nat claimed he possessed a gift of prophecy and that he could interpret divine revelations. He also claimed to have had several supernatural experiences. He became a self-proclaimed fiery preacher who believed that God had called upon him to avenge slavery. “I was ordained for some great purpose in the hands of the Almighty,” he said. His religious ardor tended to approach fanaticism and became more overtly political. He began to exert a powerful influence on many nearby enslaved men and women who called him “the Prophet.”

In May 1828, Turner said a spirit appeared to him, telling him that “the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.” It also told him that he should lead an assault against Satan’s forces – white slaveowners. He began to prepare and waited for another sign from God about when to take action.

By 1831, Nat’s son was enslaved by Piety Reese on a farm that was near the Travis farm, where Turner was enslaved. In February 1831, just days before Turner approached his future conspirators, Reese’s son John W. signed a note that put Turner’s son up as collateral for a debt that he, Reese, had struggled to pay.

This sign came on February 12, 1831, when Southampton experienced a solar eclipse, indicating God wanted the revolt to commence. He thought that revolutionary violence would force Whites to acknowledge the brutality of slavery and wanted to spread “terror and alarm” among Whites.

Turner soon shared his idea of revolting with five other enslaved men whom he “had the greatest confidence”—Hark, Sam, Nelson, Will, and Jack. Turner and his supporters began strategically planning the revolt, ensuring it went undetected. The rebels decided to keep the revolt small and did not stockpile weapons. Instead, the conspirators accepted Turner’s strategy of ” slaying my enemies with their own weapons.”

Turner began communicating his plans to a small circle of trusted fellow slaves from his neighborhood. These scattered men had to find ways to communicate their intentions without revealing the plot. Turner entrusted his wife, Cherry, with “his most secret plans and papers.”

Keeping the revolt small meant whites were less likely to uncover the conspiracy. However, it also created a new hurdle — how to get enslaved people and free Blacks who had not heard about the revolt to join them.

The original conspirators agreed to begin the revolt on July 4, 1831, but Turner fell ill and had to delay it.

The conspirators continued their planning and recruitment until Turner received another sign. On August 13, a strange atmospheric disturbance caused the sky to turn blue-green, which indicated to Turner that it was time to begin his rebellion.

The conspirators’ plan would begin with a sudden strike and kill whites, including women and children, indiscriminately. Hearing about the rebels’ power and success, the rebels hoped it would lead enslaved people and free Blacks to rally. The plan was a long shot, but the five conspirators were willing to stake their lives on it. On Saturday evening, August 20, Turner and the other conspirators planned a feast for the men who had joined the revolt the following day. The five original conspirators added two more when they gathered the next day. After a feast and a trip to Joseph Travis’s cider press, the conspirators were ready to begin the revolt. Having gathered many recruits, Turner planned to capture the armory at the county seat in Jerusalem (now Courtland) to press on to the Dismal Swamp, 30 miles to the east, where capture would be difficult.

On the night of August 21, with seven fellow enslaved people he trusted, Nat launched a campaign of total annihilation, murdering the Travis family in their sleep and marching toward Jerusalem. As the small army moved through the countryside, 40 men joined them, which later grew to 60, then 70 people.

Less than 24 hours after the revolt began, the rebels encountered organized resistance and were defeated in an encounter at James Parker’s farm. Following this setback, Turner and other rebels scrambled to reassemble their forces. By evening, when they camped at Thomas Ridley’s plantation, their force numbered 40.

In two days and nights, they axed or beat to death 69 white men, women, and children in Southampton County.

On August 23, 1831, Governor John Floyd received a hastily written note from Southampton County postmaster James Trezvant stating “that an insurrection of the slaves in that county had taken place, that several families had been massacred, and that it would take a considerable military force to put them down.”

Doomed from the start, Turner’s insurrection was handicapped by a lack of discipline among his followers, and only 75 Black Americans rallied to his cause. Angry white vigilantes killed dozens of slaves and drove hundreds of free persons of color into exile in the reign of terror that followed. Armed resistance from the local whites and the arrival of the state militia — a total force of 3,000 men — provided the final crushing blow. Only a few miles from the county seat, the insurgents were dispersed and either killed or captured — at least 100 African Americans were killed by whites in suppression of the rebellion.

Within a day of suppressing the rebellion, the local militia was joined by detachments from the U.S.S. Natchez and U.S.S. Warren in Norfolk and militias from neighboring counties in Virginia and North Carolina. Brigadier General William Henry Brodnax commanded the Virginia militia.

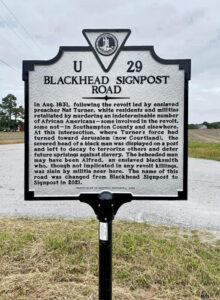

In Southampton County, Blacks suspected of participating in the rebellion were beheaded by the militia, and “their severed heads were mounted on poles at crossroads as a grisly form of intimidation.” A local road (now Virginia State Route 658) was called “Blackhead Signpost Road” after it became the site of one such display.

However, white leaders in Southampton became increasingly confident that the revolt had been suppressed and worked to limit the extralegal killing of Black people. Instead, white leaders made sure that the remaining suspected rebels were tried, which also meant that the white enslavers would receive compensation from the state for condemned enslaved people.

Rumors quickly spread that the slave revolt had gone as far south as Alabama. Fears led to reports in North Carolina of slave “armies” on highways, burning and massacring the White inhabitants of Wilmington, North Carolina, and marching on the state capital. The fear and alarm resulted in White violence against Blacks on flimsy pretenses.

“The slaughter of many blacks without trial and under circumstances of great barbarity.”

— Richmond Whig

The violence continued for two weeks after the rebellion when General Eppes ordered a halt to the killing.

In a letter to the New York Evening Post, Reverend G.W. Powell wrote that “many negroes are killed every day. The exact number will never be known.” A company of militia from Hertford County, North Carolina, reportedly killed 40 Blacks in one day and took $23 and a gold watch from the dead. Captain Solon Borland, leading a contingent from Murfreesboro, North Carolina, condemned the acts “because it was tantamount to theft from the White owners of the slaves.”

Modern historians concur that the militias and mobs killed as many as 120 Blacks, most of whom were not involved with the rebellion.

The trials of suspected enslaved rebels began on August 31, 1831. The trials were held in the Courts of Oyer and Terminer, meaning the suspects were tried without a jury before a panel of slaveholding judges. Accused rebels each had paid appointed defense attorneys, demanded properly drawn charges, and required that the prosecutor present credible evidence that the accused were guilty of a crime. The majority of the trials were completed within a month. Ultimately, 30 slaves and one free Black man were condemned to death. Of these, 19 were executed, and Governor John Floyd commuted 12.

In the meantime, Turner eluded capture, during which time, his wife Cherry was “beaten and tortured in an attempt to get her to reveal his plans and whereabouts.”

“Some papers [were] given up by his wife, under the lash.”

— Richmond Constitutional Whig reported on September 26, 1831

An 1831 reward notice described Turner as:

[He is] 5 feet 6 or 8 inches high, weighs between 150 and 160 pounds, rather “bright” [light-colored] complexion, but not a mulatto, broad shoulders, larger flat nose, large eyes, broad flat feet, rather knockkneed, walks brisk and active, hair on the top of the head, very thin, no beard, except on the upper lip and the top of the chin, a scar on one of his temples, also one on the back of his neck, a large knot on one of the bones of his right arm, near the wrist, produced by a blow.

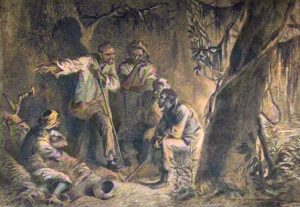

After hiding for six weeks in Southampton County, Benjamin Phipps, a farmer, found Nat hiding in an earth depression created by a large fallen tree, covered with fence rails on October 30. Once detected, Turner was forced to move, could not elude the renewed manhunt, and was captured. He arrived at the prison in Jerusalem around 1:00 p.m. on October 31. He was examined by James Trezvant and James W. Parker, two of the most prominent political figures in Southampton County. The examination lasted over an hour, and witnesses found Turner “quite communicative.”

While in prison awaiting trial, he confessed knowledge of the rebellion to attorney and slavery apologist Thomas R. Gray. Gray took the final version of The Confessions of Nat Turner to Washington, D.C., to register it for copyright.

Turner stood trial on November 5, 1831, and pleaded not guilty, as he believed his rebellion had been the work of God. Ultimately, he was found guilty and hanged on November 11. The Confessions of Nat Turner was published by the end of November 1831.

Nat Turner’s revolt prompted a prolonged debate in the Virginia General Assembly of 1831-1832. While many statesmen adhered to the Jeffersonian idea that the ending of slavery was desirable, no coherent plan for eventual abolition emerged. Virginia’s sponsorship of colonization of Africa, a popular solution to the problem, in reality, became simply a way to remove free blacks, who were thought to be a bad influence on slaves.

As a result of Turner’s actions, Virginia’s legislators enacted more laws to limit the activities of African Americans, both free and enslaved. The freedom of slaves to communicate and congregate was directly attacked. No one could assemble a group of African Americans to teach reading or writing, nor could anyone be paid to teach a slave. Preaching by slaves and free blacks was forbidden. Spreading terror throughout the white South, other states also enacted oppressive legislation against African Americans.

In the North, the abolitionist movement intensified as news of Turner, his rebellion, and his fate spread. Turner’s rebellion was one of the many events that increased sectional tensions in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Before the Civil War, Republican presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln reminded a New York audience of what he called the Southampton Insurrection, suggesting that slavery revolts were a threat before John Brown or the rise of the Republican Party.

African Americans have generally regarded Turner as a resistance hero for avenging the suffering of African Americans. James H. Harris, who has written extensively about the history of the Black church, says that the revolt “marked the turning point in the black struggle for liberation.” According to Harris, Turner believed that “only a cataclysmic act could convince the architects of a violent social order that violence begets violence.”

In 1988, Turner was included in the Black Americans of Achievement biography series for children with the book Nat Turner: Slave Revolt Leader by Terry Bisson. Coretta Scott King wrote the book’s introduction.

In 1991, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources dedicated the “Nat Turner Insurrection” historic marker on Virginia State Route 30 near Courtland, Virginia.

In 2012, Lonnie Bunch, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, said, “The Nat Turner rebellion is probably the most significant uprising in American history.”

The sword Turner is believed to have been used in the rebellion and is displayed at the Southampton County Courthouse.

In 2021, the Virginia Department of Cultural Resources dedicated the “Blackhead Signpost Road” historic marker at the intersection of Virginia State Route 35 and Meherrin Road. Nat Turner’s Rebellion is celebrated as part of Black August, a month to remember Black resistance and political prisoners.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, January 2025.

Also See:

African-Americans – From Slavery to Equality

African American History in the United States

Slavery – Cause and Catalyst of the Civil War

Sources:

American Battlefield Trust

Encyclopedia Britannica

Encyclopedia of Virginia

Find-a-Grave

Library of Virginia

Wikipedia – Nat Turner

Wikipedia – Nat Turner Rebellion