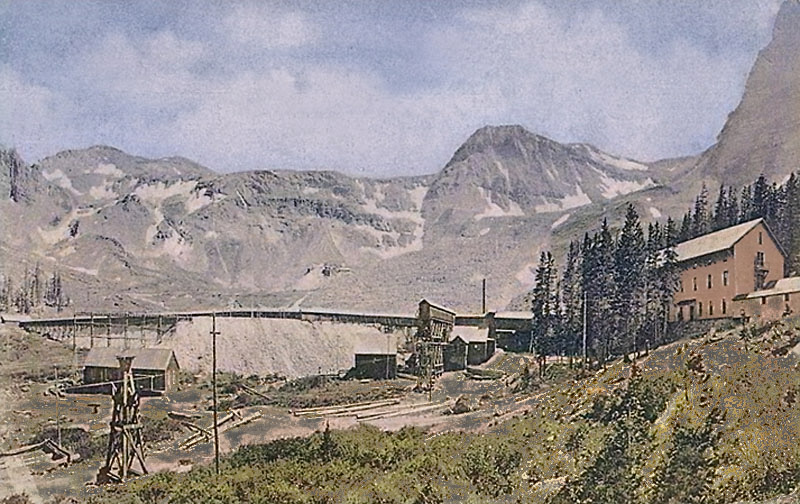

Camp Bird Mine near Ouray, Colorado.

The Camp Bird Mine, between Ouray and Telluride, Colorado, was a highly productive old gold mine in the San Juan Mountains. Thomas F. Walsh discovered gold here in 1896.

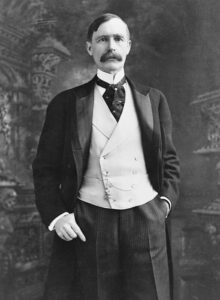

An immigrant from Ireland, Thomas Walsh came to the United States as a young man in 1869 and first settled in Massachusetts. In the early 1870s, Walsh headed west, settling in Colorado, where he was paid well for his carpentry skills. However, he was attracted to the opportunities that came with the gold rush, including trading goods and services at inflated prices, as opposed to gold mining itself. Gradually, he became increasingly interested in the gold industry and soon traded mining equipment to prospectors in exchange for their mining claims. He also studied mining technology at night.

In 1877, he moved to Leadville, Colorado, with a small fortune of between $75,000 and $100,000. He married Carrie Bell Reed in July 1879, and the couple had two children. Along with his wife, he ran the Grand Central Hotel in Leadville.

Eventually, Walsh was overcome by gold fever and took a methodical and careful approach to prospecting. He was soon prospecting further west in the Imogene Basin above Ouray. Though most miners had given up on the area due to the silver panic of 1893, Walsh was undaunted. He was looking for gold and buying up old claims. In 1896, he discovered rich gold ore on one of the claims. He operated secretly through the rest of the year and continued to buy more claims.

Needing help with his discovery, he opened the mine publicly. The mine was named after the numerous ravens who frequently stole food from miners’ camps. The mine’s development proceeded rapidly, and his Camp Bird Gold Mine near Ouray, Colorado, soon produced $5,000 a day in ore.

In 1898, an aerial tramway was built to transport ore from the mine to the mill a couple of miles down the mountain. The small settlement of Camp Bird grew at the head of Canyon Creek. It consisted of many small white-frame homes with gabled green roofs, a school, a general store, and a post office that opened in 1898. That year, an aerial tramway was built to transport ore from the mine to the mill a couple of miles down the mountain. The largest structure was the huge red mill, which had a sloping roof to prevent lifting the ore. Pack trains, wagons, and winter freight sleds hauled supplies and ore along the narrow shelf road between Ouray and Camp Bird.

Several miles above the town, at the end of the aerial tram, the first boarding house for the miners was built in 1899. By the end of the year, over 200 men were employed. The boarding house would grow and soon become a massive three-story building that housed up to 400 miners. The house was ornate and had electric lights, steam heat, modern plumbing, and a reading room. No expense was spared in the construction of the boarding house, which was described in a 1899 newspaper article:

“A boarding house capable of accommodating 400 men has been built and equipped with modern conveniences as well as the average hotel – electric light, steam heat, hot and cold water, porcelain bathtubs, commodes, sewer connection, fire apparatus, library, reading room, stationary porcelain basins, and all the other etceteras that contribute to the comforts of a home.”

Walsh wanted to treat miners fairly, and the lavish boarding house was part of his plan. Camp Bird was also one of the first mines in the West to implement eight-hour work days; wages were high, equipment was modern, and safety and working conditions were regarded as exceedingly good.

In 1899, the Silverite-Plaindealer newspaper called Camp Bird “The Greatest Gold Mine in Colorado on the Whole Earth.”

On Monday, October 2, 1899, a Mount Sneffels stagecoach stopped at the mill and picked up two days of bullion worth $12,000 in gold from the Camp Bird Mine. James Knowles of the Camp Bird Mine accompanied the bullion, and a second guard, Pat Hennesey, rode behind on horseback. W.W. Almond drove the stage. They stashed the loot in an iron box beneath the driver’s seat.

At about 2:30 p.m., when the stagecoach was about a mile this side of the Camp Bird mill, an unsuccessful attempt was made to rob the treasure box containing gold bullion. At that time, a man jumped out from a bank of willows and pointed a Winchester at the stage driver, commanding him to put up his hands.

Almost simultaneously, another armed and masked man came from the bushes in the rear of Pat Hennessy and ordered him to throw up his hands and dismount. With a Winchester drawn on him, Hennessey was marched past the stage to where the other outlaw had the driver and the passenger. The robbers were described as medium-sized, well-dressed, but their clothing was smeared with dust. They wore slouch hats and black masks with large eyeholes covering their faces.

The bandits ordered the three men to lie flat down while the first bandit stood guard. The second rummaged through the stage, grabbing mail pouches and baggage, but somehow failed to find the gold. Although Hennesey had a .45 revolver hidden inside his coat, he found no opportunity to use it.

Turning to the driver, the searcher demanded that he reveal the hiding place of the Camp Bird gold sacks. The driver pleaded ignorance, and the outlaws reloaded the stage with the mail pouch and luggage and ordered the prisoners to get up and get on the stage. The men did as they were told, and when all were aboard, they were commanded to drive on. It was the first time an attempt had been made to rob them.

Stealing Hennesey’s horse, the bandits rode away with the mail pouch and minor items from the stage. It was thought they left in the direction of the Revenue Mill, west of the Camp Bird properties. The stagecoach then proceeded to Ouray rapidly and reported the incident.

When the stage reached Ouray, they called back to the Camp Bird and Revenue Mines. In Edgar, Under-Sheriff McQuilken and City Marshal O.C. Van Houton in Ouray also formed posses, and Camp Bird manager J.W. Benson offered a $1,000 reward for the bandits’ apprehension. Inspired by the reward, numerous miners and mill workers in the region quit work and went searching for the robbers.

Later, a man in the area reported that he was robbed of his horse around that time by two masked men in an excited frame of mind.

By 8:00 p.m., the posse had no clue to the bandits’ whereabouts.

At 9:30 p.m., Under Sheriff McQuilkin returned from the pursuit, saying his party saw the bandits near Yankee Boy Basin when they were on foot. However, the robbers saw the posse, retreated behind a ledge of rocks, and opened fire. Because the officers could not get them within range, they retreated and gave up the chase. About 20 shots were fired without effect.

On October 14, 1899, a newspaper stated that one of the bandits, John “Kid” Adams, was tracked to the bandits’ stronghold near Norwood and was killed by San Miguel County Deputy Sheriff George Kinchen. Kid Adams also went by the name of John Carter. The fate of the other bandit, who was thought to have been Ed Perry, is not known.

For the next year, the Camp Bird Mine sent its gold to the city on armed stagecoaches, bringing the daily price down from $6,000 to $8,000.

By the end of 1900, the mine comprised 103 mining claims on 941 acres and had 12 mills in operation. In the first years of the 20th century, Walsh’s investment in the health and happiness of his miners paid off, as the Camp Bird mine did not experience the violent labor unrest that rocked the region then.

However, with the nearly vertical walls of Canyon Creek and consistently occurring snow slides, Camp Bird Mine was one of the most dangerous places to work in Colorado, killing dozens of men and horses over the years.

In 1902, Thomas F. Walsh sold the mine for $5.2 million. Walsh died in 1909. His daughter, Evalyn Walsh McLean, later purchased the Hope Diamond and devoted several chapters to the mine in her autobiography, Father Struck It Rich.

In 1918, the post office at Camp Bird closed.

In the subsequent decades, Camp Bird Mine closed and opened intermittently depending on the economy.

Over the years, the Camp Bird Mine has placed among Colorado’s top three gold mines, with total production between $30 and $50 million.

The Camp Bird Mine filed for a permit to resume mining in late 2007 but remained inactive. In 2012, the mine received permits to rehabilitate existing mine workings, but again, it remained inactive.

In August 2017, the Environmental Protection Agency and the State of Colorado signed an Administrative Order with Caldera Mineral Resources, which purchased the property from bankruptcy. The Order specified on-site erosion control “to prevent the downstream migration of contaminated soil,” with work to be accomplished by October 2018.

The mine is located about six miles south of Ouray in Ouray County, Colorado. Today, Camp Bird is posted against trespassing, and permission must be obtained to travel the last two miles from Camp Bird to the original mine site. The last stretch requires a jeep, horse, or hiking boots.

Most of the mine sites have been remediated, and the equipment removed. However, the lower mill site still has some remaining houses, including the superintendent’s office and company housing.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2025.

Also See:

Colorado Ghost Towns & Mining Camps

Ouray, Colorado – Switzerland of America

Sources:

Aspen Weekly Times – October 7, 1899

Environmental Protection Agency

Today in Ouray

U.S. Forest Service

Western Mining History

Wikipedia – Camp Bird Mining

Wikipedia – Thomas Walsh