Donaldsonville, Louisiana, the parish seat of Ascension Parish, is located along the River Road of the west bank of the Mississippi River in the southern part of the state. Part of the Baton Rouge metropolitan statistical area, its population, as reported in the 2020 U.S. census, was 6,695.

Before European colonization, various Native American cultures lived along the Mississippi River for thousands of years. The Houma and Chitimacha peoples lived in the area when French colonists arrived. Descendants of both tribes are federally recognized today, and each has a reservation in Louisiana.

The French named the site Lafourche-des-Chitimachas, after the regional indigenous people and the local bayou. The colonists soon developed agriculture in the area, primarily sugar cane plantations worked by African slave labor.

During the early years of colonization, the Indians suffered high rates of fatalities due to infectious diseases.

In 1755, Acadians, expelled by the British from Acadia, began to settle in the area, where they developed small subsistence farms until 1785. Spanish Islenos, inhabitants of the Canary Islands, arrived in Spanish Louisiana between 1778 and 1783.

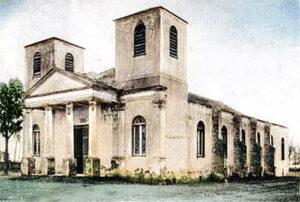

In 1772, when the territory was under Spanish rule, the militia constructed the Ascension of Our Lord Catholic Church of Lafourche, also known as the Chitimache, to serve the area. The region returned later to French control for a time.

This area was included in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and became part of the United States. Afterward, Americans began to move into the area.

In 1805, Englishman William Donaldson purchased land near Bayou Lafourche from Acadian Marguerite Allain. The following year, he commissioned architect and planner Barthelemy Lafon to plan a new town at this site. He named the settlement “La Ville de Donaldson” after himself.

In 1823, the area was reincorporated under its present name, Donaldsonville.

Donaldsonville was designated as the Louisiana capital in January 1829 due to conflict between the increasing number of Anglo-Americans, who deemed New Orleans “too noisy”, and French Creoles, who wanted to keep the capital in a historically French area. They wanted to move the capital closer to their population centers, farther north. As a result of the wealth planters gained from sugar and cotton commodity crops, they built fine mansions and other buildings in town during the antebellum years. However, its days as the capital were numbered, as it returned to New Orleans on January 8, 1831.

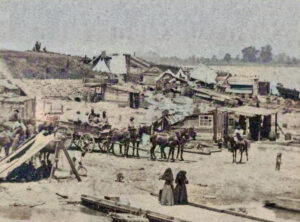

During the Civil War, Donaldsonville was bombarded by Union forces in August 1862 as part of the Union’s effort to gain control of the Mississippi River. The Union sent gunboats to Donaldsonville and warned that if shots were fired, the Union Navy would strike the area for six miles to the South and nine miles to the north and destroy every building on every plantation. Admiral David G. Farragut destroyed much of the former capital city and imposed martial law on Ascension Parish, subsequently extending it to other River parishes.

In October 1862, Lieutenant Palfrey and Colonel Richard Holcomb began building Fort Butler at the junction of Bayou Lafourche and the Mississippi River using fugitive slaves. The military took over some plantations, running them as U.S. government plantations to supply the forces and produce cotton.

Many escaping slaves entered the Union lines to gain freedom and protection at Fort Butler. General Benjamin Butler had declared them “contrabands” of war and would not return them to slaveholders. They stayed and worked with Union forces, helping build the star-shaped fort.

On February 9, 1863, Fort Butler was christened and named in honor of General Benjamin Butler, a Union commander who many people in South Louisiana widely despised. While celebrated by Yankees, Southerners had critically awarded Butler the title “Beast,” because of his orders that jailed women who insulted his troops, or anyone who was caught praying for the destruction of the United States.

A work of earth and wood, the fort was 381 feet long on the side by the Mississippi River, Bayou Lafourche protected the other, and a deep moat protected the land sides. A stockade surrounded the fort, which contained a high and thick earth parapet. There was further security from a strong lock. The fort was built to accommodate 600 men, but in 1863, a small garrison of 180 Union men, commanded by Major Joseph Bullen of the 28th Maine, was stationed there. The forces also included the 1st Louisiana Volunteers, a few Louisiana Native Guard convalescents, and some fugitive slaves.

On June 28, 1863, more than 1,000 Texas Rangers, led by General Tom Green, attacked Fort Butler at night. This battle was one of the first occasions when free blacks and fugitive slaves fought as soldiers on behalf of the Union.

“The irate naval commander, Admiral Farragut, ordered the bombardment of Donaldsonville as soon as it could be evacuated. All of the citizens of Donaldsonville… “left their homes and went to the bayou… a detachment of Yankees went to shore with fire torches in hand. The hotels, warehouses, dwellings, and some of the most valuable buildings of the town were destroyed, and Plantations… were bombarded and set afire… A citizens committee met and decided to ask Governor Moore to keep the [Confederate] Rangers from firing on Federal boats.”

— John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, 1963.

The Union kept control of the fort and ultimately won the war. The fort site has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

After the war, Donaldsonville became the third-largest black community in the state, as more freedmen moved there. In 1868, the city elected the first African American mayor in the United States, Pierre Caliste Landry, a former slave who was educated in schools on a plantation owned by the Bringier family. After the war, he advanced to become an attorney and state politician, serving in both houses of the legislature. He also became a Methodist Episcopal minister.

In 1871, the New Orleans, Mobile and Chattanooga Railroad began regular service between Donaldsonville and New Orleans.

Donaldsonville is the home of one of the oldest synagogue buildings in the United States. The wooden structure was built in 1872 by Congregation Bikur Cholim, which disbanded in the 1940s. It is now used as a hardware store. The Jewish Cemetery dates to the 1800s and is located on the corner of St. Patrick Street and Marchand Drive.

The Parish Courthouse was built from 1888 to 1889 at 300 Houmas Street. The two-story Romanesque Revival red brick building is located on landscaped grounds in the center of Donaldsonville. The east front features a large arch on the first story, with a square, red-colored brick clock tower rising above the entrance. The building burned in 1889 and was rebuilt. It continues to serve as the courthouse today.

In 1903, a two-century-old debate ended with the damming of Bayou Lafourche in favor of locks to prevent seasonal flooding in the bayou’s lower reaches. Once the debate ended, so did the talk of locks, and for two decades, Donaldsonville declined, primarily due to the mechanization of agriculture.

Between 1920 and 1930 was the period of the Great Migration, when tens of thousands of African Americans left the rural South for opportunities in northern and midwestern cities. Such changes also drew off business from the parish seat. Ascension Parish lost more than 16% of its population in that decade.

Historian Sidney A. Marchand, an attorney, was elected mayor of the city and a state legislator during that period. He served as a state Senator and contemporary of Governor Huey Long. During the mayoral administrations of Sidney A. Marchand and his son, Sidney Marchand, Jr., they directed the construction of significant infrastructure in Donaldsonville.

During the Great Depression, the area experienced significant economic struggles.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the community prospered with the addition of major industries, the construction of the Sunshine Bridge over the Mississippi, and the opening of Interstate 10.

Donaldsonville’s population reached its peak at 7,949 in 1990.

The official newspaper of the city is the Donaldsonville Chief, which has been published since 1871.

Since 2008, the River Road African American Museum, situated in the city, has been designated as part of the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail. It also has parks, Civil War grounds, and shopping centers.

Driving through Donaldsonville, visitors experience the true gateway to Cajun and Plantation Country, illuminated by numerous mansions that proudly stand along the banks of the Mississippi River. The Donaldsonville Historic District comprises approximately 50 blocks, characterized by a mix of commercial and residential properties. Its boundaries encompass 635 structures, which date mainly from the period 1865 to 1933. The 1889 Romanesque Revival Ascension Parish Courthouse dominates Louisiana Square. The district is second in size only to the French Quarter.

Located on highway LA-1, Donaldsonville is about a one-hour drive from either Baton Rouge or New Orleans.

More Information:

City of Donaldsonville, LA

609 Railroad Ave

Donaldsonville, LA 70346

225-473-4247

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Early History of the Pelican State

Sources:

Donaldsonville, Louisiana

Louisiana Destinations

National Register of Historic Places

Wikipedia