By James S. Zacharie, 1885

The City Of New Orleans

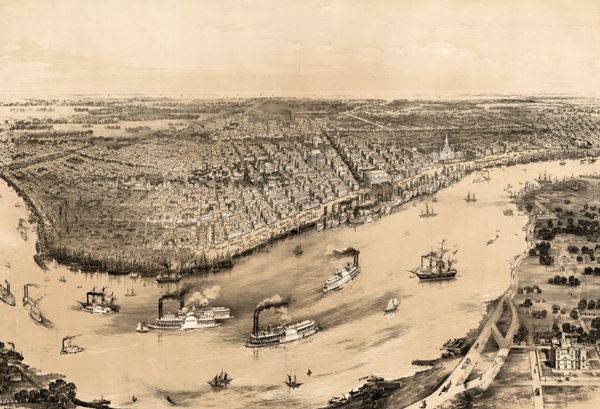

New Orleans, Louisiana 1851

It is often said that Paris is France, and it may also be said that New Orleans is Louisiana, for the city’s history is the history of the State.

The first mention of Louisiana and the Mississippi River being traversed by white men was in 1536, when a remnant of the ill-starred expedition of the Spaniards, under Panfilo de Narvaez, in the vain attempt to conquer Florida and seek gold, escaped in the West in direction to the Pacific Ocean. Narvaez had commanded the territory extending west to the River of Palms, probably the Colorado River.

Notwithstanding the failure of Narvaez, other adventurers were ready to follow. In 1537, Hernando de Soto, a native of Xeres, Spain, the favorite companion of Pizzaro in the conquest of Peru, sought and obtained permission from King Charles V at Valladolid to conquer Florida at his own cost. Landing on that coast on May 31, 1539, his well-appointed army was almost annihilated before he reached the Mississippi River two years later. In May 1542, Hernando DeSoto died at the mouth of the Red River and, according to tradition, was buried in the waters of the Mississippi River. The miserable remnant of the expedition descended the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico in July 1543 after enduring great hardships and privations. Thus, the discovery of the Father of Waters belongs to the Spaniards, and no record of other white men visiting it for 130 years exists.

In 1673, Father Jacques Marquette, a missionary monk and the Sieur Joliet from Picardy, France, with a small party from the French possessions of Canada, entered the upper Mississippi River and descended it to a point below the mouth of the Arkansas River and returned.

French Take Possession

In 1682, Robert Cavalier de la Salle, then of Fort Frontenac, Lake Ontario, was the next to descend the great river in company with Chevalier Ilenry de Tonti, an Italian veteran officer, under the patronage of King Louis XIV. On April 9, 1682, LaSalle halted on the banks of the Mississippi River, above the head of the passes, erected a cross, and, calling a notary to witness, he took solemn possession of the country in the name of his sovereign Louis XIV and named it after him — Louisiana.

In January 1699, an expedition of 300 men was sent out to colonize Louisiana. Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville commanded the expedition, and with him were his two brothers, Sauvolle and Bienville, all sons of Charles Leinoyne. A landing was made on the Bay of Biloxi, and a fort was built on a small point of land that extends out into the bay. In February, Iberville and his brother, Bienville, accompanied by Father Athanase, who had formerly been with La Salle, went in small boats to the Mississippi River, which they ascended first to the village of the Bayagoulas, where these Indians handed them letters and other relics of La Salle and Tonti. They then moved on to Pointe Coupee, which they named, and to the mouth of Red River. Returning, they traversed Lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain, naming one after Count Maurepas, who held office under their sovereign, and the other after Count Pontchartrain, the Minister of Marine. On December 7 of the same year, another fleet arrived, bringing letters appointing Sauvolle as the first Governor of the Colony and Bienville as the first Lieutenant-Governor. In 1701, Governor Sauvolle died of fever and was succeeded by Bienville. On September 14, 1712, King Louis XIV granted Anthony Crozat a charter for 15 years, with the exclusive commerce of the whole Province, from the Gulf to the Great Lakes and from the Alleghany Mountains to the Rocky Mountains on the West. By the terms of the charter, Crozat was to send, every year to Louisiana, two shiploads of colonists and, after nine years, to assume all the expenses of the Colonial administration, including those of the army, in consideration of which he was to have the privilege of nominating the officers to be appointed by the King.

In 1717, Crozat, finding this colonial scheme a failure, voluntarily surrendered his charter to the King. On August 13, a Council of State was held at Versailles, presided over by the Duke of Orleans, Regent of France during the minority of Louis XV, at which it was decided that as the colonization of Louisiana was a commercial undertaking, it should be confined to a company. Then, the Parliament of Paris granted and registered a charter on September 16, 1717, under the name of the Company of the Indies. The Mississippi Company, as it was sometimes called, was granted the exclusive privilege of trading with Louisiana for 25 years to administer the colony, appoint officers, and maintain an army. Its leading spirit was John Law, an intelligent and scheming Scotchman long domiciled in Paris. All the lands, coasts, harbors, and islands in Louisiana were granted to the company on the condition of furnishing to every King of France, on his accession to the throne, a crown of gold of the weight of 30 marks. Louisiana was supposed to be a Garden of Eden, with the most useful fruits and a new Eldorado, teeming with mines of gold, silver, and precious stones. As such, the Province was placed before the public, and vast sums of money were invested in the company’s shares, expecting a rich harvest of dividends. However, poor administration, disease, and wars with the Indians caused the scheme to fail, and the Mississippi bubble burst, scattering ruin on all sides. On November 15, 1731, the Mississippi Company, finding the colony unsuccessful after 14 years, surrendered their charter to the King.

Founding of New Orleans

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville.

Sailing along the shores of Lake Pontchartrain in 1718, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville discovered the small stream now called Bayou St. John and, ascending it, encamped for the night on the Metairie Ridge. The tract of country lying between the headwaters of Bayou St. John and the banks of the Mississippi River was selected as the site of the future city. This space was then covered with a primitive forest and, owing to the annual inundations of the river, was swampy and marshy and cut up with a thousand small ravines and pools of stagnant water when the river was low. Bienville and 50 soldiers started to clear the ground of its primitive growth, and, unmolested by the Indians, whose sole representative was an old Indian woman who sang a chant. “The Spirit tells me,” she sang, ” that the time will come when, between the river and the lake, there will be as many dwellings for the white men as trees are standing now. The haunts of the red man are doomed, and faint recollections and traditions concerning the very existence of his race will float dimly over the memory of his successors, as unsubstantial, as vague, and obscure as the mist that shrouds on a winter morning, the bed of the Father of Waters.”

Bienville undoubtedly chose the site on the narrowest strip of land between the river and the lake, hoping that someday in the future, the capital would have a lake and riverfront. Two plans for the city seem to have been executed, one in 1719 by Louis Henri De la Tour, Chief Engineer of the Province, and the other by Adrien de Pauger, a royal engineer employed by the Western Company. The land was laid off into 66 squares of 300 feet each, separated by streets and divided into 12 lots. The lots were divided among the resident population. In 1719, an inundation drove the inhabitants from the infant city, and for a time, it was abandoned.

However, just a few years later, in 1722, it became the colony’s capital. At that time, it contained 200 inhabitants, and the buildings consisted of about 100 log cabins, placed without much order, a large wooden warehouse, two or three dwellings, and a storehouse that served as a chapel. The city was surrounded by a large ditch and fenced in with sharp stakes wedged close together. In 1727, Governor Etienne de Perier built a levee or embankment in front of the city, 1800 yards in length and 18 feet in width on top, which protected the city from the annual overflows of the Mississippi River.

Lousiana Ceded to Spain

The colony of Louisiana continued for several years to belong to France until King Louis X., in return for her services as an ally during the French and Indian War, ceded Louisiana to Spain in 1762. Spain accepted this cession, and Antonio de Ulloa was sent out as Governor to receive the colony transfer. The colonists violently opposed the cession of the country, and De Ulloa never formally took possession but departed with his troops after contenting himself with only hoisting the Spanish flag on the fort at Balize and remaining there for some time. The state of affairs was reported to the Spanish King, Charles III, and his council, led by the Duke of Alba, decided to take the colony by force. A second expedition, consisting of 24 man-of-war ships with a large force of troops commanded by General Alexander O’Reilly, a Spanish officer of renown, was sent in 1769 to take possession of the country.

Spanish Take Possession

On August 15, 1769, the French Governor, Charles Aubrey, went down the river to offer his respects to the new Spanish Governor, Alejandro O’Reilly, who was on his way up, and to come to an understanding with him as to the manner and time of taking possession of the colony. Upon consultation, they decided that August 18 would be the date for that ceremony. On the 16th, Aubrey returned to New Orleans and issued a proclamation, enjoining the town’s inhabitants. The most respectable among the neighboring country will be at the ceremony and ready to present themselves to His Excellency Don Alexandro O’Reilly to assure him of their entire submission and inviolate fidelity to His Catholic Majesty. On the morning of the 17th, the Spanish fleet of 24 ships appeared in front of New Orleans. Immediately, all the necessary preparations were made for landing, and flying bridges were dropped from the vessels to the bank of the river. On the 18th, early in the day, the French Governor, with a numerous train of officers, came to compliment the new Governor, who went ashore in company with his visitors and proceeded with them to the house that was destined for him. But, before noon, O’Reilly returned to his fleet to prepare for the landing of the whole of his forces.

At 5 p.m., a gun fired by the flagship gave the signal for the landing of the Spaniards. With Aubrey at their head, the French troops and the colony militia were already drawn up in a line parallel to the river, in front of the ships, in that part of the public square nearest to the church. On the signal being heard, the Spanish troops were seen pouring out of the fleet in solid columns and moving with admirable precision to the points designated for them. These troops, numbering some 2,600 men, were among the choicest of Spain and had been picked by O’Reilly himself. With colors flying and with the rapidity of motion of the most practiced veterans, they marched on, battalions after battalions, exciting the admiration and the awe of the population with their martial aspect and their brilliant equipment. The heavy infantry drew themselves up in perpendiculars on the right and left wings of the French, thus forming three sides of a square. Then came a heavy train of artillery of 50 guns, the light infantry, and the companies of mountain riflemen, with the cavalry composed of 40 dragoons and 50 mounted militiamen from Havana. All these corps occupied the fourth side of the square near the river and in front of the French, who were drawn up near the Cathedral. All the vessels were dressed in their colors, and the riggings were alive with the Spanish sailors in their holiday apparel. Suddenly, they gave five long and loud shouts of “Viva el Rey—Long live the King,” to which the troops in the square responded similarly. All the bells of the town pealed merrily; a simultaneous discharge from the guns of the 24 Spanish vessels enveloped the river in smoke; with emulous rapidity, the 50 guns that were on the square roared out their salute, making the ground tremble as if convulsed with an earthquake; all along the dark lines of the Spanish infantry flashed a sheet of fire, and the weaker voice of musketry, also shouting in jubilation, attempted to vie with the thunder of artillery. All this pomp and circumstance of war announced that General O’Reilly was landing.

New Orleans Square today.

He soon appeared in the square, where he was received with all the honors due to a Captain-general, drums beating, banners waving, and all sorts of musical instruments straining their brazen throats, and by their wild and soul-stirring sounds causing the heart to leap and the blood to run electrically through the hot veins. He was preceded by splendidly accoutered men who bore heavy silver maces, and his entourage, which was of the most imposing character, was well calculated to strike the people’s imagination. With a slightly halting gait, he advanced towards the French Governor, who, with the members of the Council and all the men of note in the colony, stood near a mast that supported the flag of France.

Immediately behind O’Reilly followed the officers of the colonial administration of Louisiana: Don Joseph Loyola, the commissary of war and intendant; Don Estevan Gayarre, the Contador, or royal comptroller; and Martin Navarro, the treasurer, who were to be restored to their respective functions, which had been interrupted by the revolution. “Sir,” said O’Reilly to Aubrey, “I have already communicated to you the orders and the credentials with which I am provided to take possession of this colony in the name of His Catholic Majesty and also the instructions of His most Christian Majesty that it be delivered up to me. I beg you to read them aloud to the people.”

Aubrey complied with this request and then, addressing the colonists, by whom he was surrounded, said: “Gentlemen, you have just heard the sacred orders of their most Christian and Catholic Majesties about the Province of Louisiana, which is irrevocably ceded to the crown of Spain. From this moment, you are the subjects of His Catholic Majesty. By the orders of the King, my master, I absolve you from your oath of fidelity and obedience to His most Christian Majesty.”

Then, turning to O’Reilly, Aubrey handed him the keys to the town’s gates. The banner of France sunk from the head of the mast. Where it waved and was replaced by that of Spain. Following Aubrey’s example and orders, the French shouted five times, “Viva el Reyl —Long live the King!” which was repeated three times by the Spanish troops, who recommenced their firing in unison with the fleet. Then O’Reilly, followed by the principal Spanish officers and accompanied by Aubrey and his entourage, proceeded to the Cathedral, where he was received at the threshold by the clergy with all the honors of the Pallium and with the other usual solemnities.

The curate or vicar-general, in the name and on behalf of the people, addressed to the General a pathetic harangue coupled with the most caressing protestations of fidelity on his part. The General answered with concise eloquence, declaring his readiness to protect religion, to cause the ministers of the sanctuary to be respected, to support the authority of the King and the honor of his arms, to devote himself to the public good, and to do justice to all. He then entered the church, where a Te Deum was sung, during which the troops and the fleet renewed their discharges in token of rejoicing. When the pious ceremony was over, O’Reilly and Aubrey returned to the public square, where all the Spanish troops filed off before the Governors in the most redoubtable order and equipage, says Aubrey, in one of his dispatches, and, after having saluted them retired to their respective quarters.”

New Orleans Fortified by the Spanish

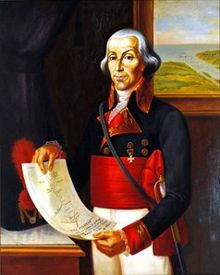

Baron de Carondelet.

In 1794, the Spanish Governor, Baron de Carondelet, fortified the city after a plan drawn by himself. His objective was not only to provide for defense from outside enemies but to place his guns so that they could bear upon the town and keep the inhabitants in subjection. Collot, a French General who visited New Orleans in 1796, described the fortifications as consisting of:

“of five small forts and a great battery. On the side that fronts the river are two forts that command the river and the road. Their shape resembles a regular pentagon, with a parapet 18 feet thick, coated with brick, with a ditch and covered way. Each of these forts is a barracks for 150 men and a powder magazine. Their artillery is composed of a dozen twelve and eighteen-pounders. Between these two forts—that is, that on the right, which is most considerable — is called “St. Charles,” the other “St. Louis.” In the rear, and to cover the city on the land side, are three other forts. There is one at each of the two salient angles of the long square forming the city and a third between the two, a little beyond the line, to form an obtuse angle. These three forts have no covered way and are not revetted but are strengthened with friezes and palisades. They are armed with guns and have accommodations for 100 men. The one on the right is called Fort Burgundy, on the left, St. Ferdinand, and that of the middle St. Joseph. The five forts and the battery cross their fire with one another and are connected by a ditch of 40 feet in width by seven in depth. With the earth taken out of the ditch, there has been formed on the inside of a parapet three feet high, on which have been placed, closely serried, a line of 12-foot pickets. The back of those pickets is a small causeway. The earth has been cast to render the slope exceedingly easy and accessible. Three feet of water is always kept up in the moats, even during the driest season of the year, using ditches communicating with a draining canal. It cannot be denied that these miniature forts are well-kept and trimmed up. But, particularly because of their ridiculous distribution and their want of capaciousness, they look more like playthings Intended for babies than military defenses. For there is not one which cannot be stormed, and 500 determined men could not carry a sword. Once a master of one of the principal forts, either St. Louis or St Charles, the enemy would not need to mind the others because, bringing the guns to bear upon the city, it would be forced to capitulate immediately or be burnt up in less than an hour and have its inhabitants destroyed, as none of the forts can admit more than 150 men. We believe that Monsieur de Carondelet, when he adopted this bad system of defense, thought more of securing the obedience of the subjects of his Catholic Majesty than of providing a defense against the attack of a foreign enemy, and, in this point of view, he may be said to have completely succeeded.”

Retrocession of Louisiana to France

Bv the treaty of San Ildefonso, made on October 1, 1800, Spain engaged herself to cede Louisiana to France. This treaty was kept secret, as France, who was then at war with England, feared that that power would seize it. France sold Louisiana to the United States and appointed Laussat Prefect of the colony for the intervening time and a commissioner to transfer the colony to the United States.

On November 30, 1800, the Marquis of Casa-Calvo and Governor Salcedo, commissioners on the part of Spain, and Laussat, commissioner on the part of France, accompanied by a vast entourage of the clergy, all the civil and military officers in the employ of France and Spain, and many other persons of distinction, met in the City Hall, where Laussat exhibited to the Spanish commissioners an order from the King of Spain for the delivery of the colony, and his credentials from the French Government to receive it. Thereupon, the keys of New Orleans were handed to Laussat. Salcedo and Casa-Calvo declared that, from that moment, according to the powers vested in them, they put the French commissioners in possession of Louisiana and its dependencies, in all their extent, such as France ceded them to Spain and such as they remained under the successive treaties made between his Catholic Majesty and other Powers. They further declared that they absolved from their oath of fidelity and allegiance to the crown of Spain, such as his Catholic Majesty’s subjects in Louisiana, who might choose to live under the authority of the French Republic. A record was made of these proceedings in French and Spanish. The three commissioners walked to the main balcony, where the Spanish flag was saluted by a discharge of artillery on its descent from a pole erected on the public square in front of the City Hall; that of the French Republic was greeted in the same manner on its ascent. The Spanish troops and some of the colony’s militia occupied the square. It was remarked that the militia had mustered up with difficulty and did not exceed one hundred and fifty men. It was an indication of an unfavorable feeling, which had been daily gaining strength and which Laussat attributed, in his dispatches, to the intrigues of the Spanish authorities. Although the weather had been stormy in the preceding night and the morning and continued to be threatening, the crowd around the public square was immense and filled, not only the streets but also the windows and even the very tops of the neighboring houses.

Sale of and Possession of Lousiana to the United States

Lousiana Purchase.

Bonaparte, fearing England would seize Louisiana, authorized his ministers, Barbe Marbois and Talleyrand, to negotiate with the United States, represented by Livingston and Monroe. The negotiations resulted in a treaty signed in Paris on April 30, 1803. France ceded Louisiana to the United States for 15 million dollars, of which four million was to be devoted to the payment of what was due by France to the citizens of the United States. When Bonaparte was informed of the treaty’s conclusion, he celebrated: “This accession of territory strengthens the power of the United States forever, and I have just given to England a maritime rival that will, sooner or later, humble her pride.”

New Orleans in the 1800s.

“On Tuesday, December 20, 1803, the French Prefect, Laussat, ordered all the militia companies to be drawn up under arms, on the public square, in front of the City Hall. The crowd of spectators was immense, and the finest weather favored the public’s curiosity. The Commissioners of the United States, William Claiborne, and James Wilkinson, arrived at the city’s gates with their troops and, before entering, were reconnoitered, according to military usages, by a company of the militia grenadiers. On entering the city, the American troops were greeted with a salute of 21 guns from the forts and formed on the opposite side of the square, facing the militia. At the City Hall, the Commissioners of the United States exhibited their powers to Laussat. The credentials were publicly read, next to the treaty of cession, the powers of the French Commissioner, and, finally, the process-verbal. The Prefect proclaimed the delivery of the Province to the United States, handed the city’s keys to Claiborne, and declared that he absolved from their allegiance to the French Republic such of the inhabitants as might choose to pass under the new domination. Claiborne now rose and congratulated the people on the event that irrevocably fixed their political existence and no longer left it open to the caprices of chance.

He assured them that the United States received them as brothers and would hasten to extend to them a participation in the invaluable rights forming the basis of their own unexampled prosperity. Meanwhile, the people would be protected in the enjoyment of their liberty, property, and religion; their commerce would be favored, and their agriculture encouraged.

The three Commissioners then went to one of the balconies of the City Hall. On their appearance, the French flag, floating at the top of a pole in the middle of the square, came down, and the American flag went up. Thus, the French domination, if it can be so called, ended 20 days after it had begun. The Spanish Government had lasted 34 years and a few months.”

Lousiana as a Territory and a State

The President appointed William Claiborne governor of the Province and immediately organized a government. In 1804, Congress passed an act dividing Louisiana into two parts. The upper portion was called the District of Louisiana, with St. Louis as the capital, and the lower portion was the Territory of Orleans, with New Orleans as the capital. This act remained in force until 1805, when a new act was passed, reorganizing the Territory of Orleans with an elective legislative council.

In 1812, Congress called a Constitutional Convention. This Convention adopted a Constitution modeled after that of Kentucky, and on April 8, 1812, Congress passed the act admitting Louisiana into the Onion as the 18th State. A portion of West Florida, the country east of the Mississippi River and north of Lake Pontchartrain, was annexed, and Louisiana thus constituted and comprised 41,347 square miles.

It became part of the United States of America, and Claiborne was elected the new State’s first governor. During Governor Claiborne’s administration, the United States was at war with England, and the British sent an expedition against New Orleans, which resulted in the Battle of New Orleans and a loss to the attackers.

Louisiana as a State

After the defeat of the British and their retreat, peace was declared, trade was immediately revived, and internal improvements commenced. The culture of sugar developed itself every year, and immigration set in. The State and city increased in population and continued to prosper until the civil war was declared.

On January 26, 1861, the Convention adopted the Ordinance of Secession, and Louisiana joined the Confederate States of America. Many regiments of troops were sent to the Confederate Army and took their share of the perils of the battlefield.

In April 1862, the Federal fleet under Admiral Farragut passed the forts and batteries on the river, and New Orleans was captured. United States forces held the city, and from it, at different times, were sent expeditions to the interior. These expeditions were unsuccessful in the State, as, except for New Orleans and its immediate vicinity, it remained in the hands of the Confederates. On the approach of the Federal forces, the State officers evacuated the capital, and the capital was transferred to Shreveport. During this period, a convention was called, and a State government was organized in New Orleans under the protection of the Federal army.

The war caused great destruction in Louisiana. Sugar houses and gins were burned, and sugar planting was suspended, but the large amount of cotton in the interior started to trade again. The State Government of Shreveport ceased with the cessation of hostilities, and the only State authorities remaining were those of New Orleans. These authorities continued to act until 1866.

In 1866, the July Riots took place, and Congress immediately put the State under military rule with a temporary State government. In 1868, a convention formed a new constitution and was recognized by Congress as a State. Political matters thus assumed an unsettled state for several years. They remained so until 1879, when a convention was called to form a new constitution, and, thenceforth, all became settled, and the people directed their energies to build the State up again and restore its cities and plantations to their antebellum prosperity.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2024. Source: New Orleans Guide, by James S. Zacharie, New Orleans News Company, 1885.

Also See: