Pamunkey in dance costumes, 1899.

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is a federally recognized tribe that controls the Pamunkey Indian Reservation in King William County, Virginia. Historically, they spoke the Pamunkey language, of which very little has been preserved. They are one of eleven Native American tribes in Virginia and an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands.

The Pamunkey tribe’s history dates back 10,000 to 12,000 years. The historical Pamunkey people were part of the Powhatan Confederacy of Algonquian-speaking nations. When the English arrived in 1607, the Powhatan Confederacy comprised over 30 nations, estimated to total about 10,000 to 15,000 people. The Pamunkey comprised about one-tenth to one-fifteenth of the total, about 1,000 people.

Their traditional way of life included fishing, trapping, hunting, and farming. Utilizing the Pamunkey River as a primary mode of transportation and food source, the river also provided access to hunting grounds and other tribes.

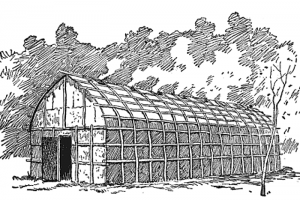

Pamunkey villages were seldom permanent settlements, moving their fields and homes about every ten years to allow the land to lay fallow and recover from cultivation. Pamunkey homes, called yihakans, were long and narrow and described as “longhouses” by English colonists. They were made from bent saplings lashed together at the top to make a barrel shape. They then covered the saplings with woven mats or bark. When the heat and humidity increased in summer, the mats could be rolled up or removed to allow more air circulation. Inside, they built bedsteads along both walls made of posts put in the ground, about a foot high or more, with small poles attached. The framework was about four feet wide, over which reeds were placed. One or more mats were placed on top for bedding; more mats or skins served as blankets, with a rolled mat for a pillow. The bedding was rolled up and stored daily to make the space available for other functions.

Initial contact with European Colonists began around 1570. From then on, more contact was made at intervals by the Spanish, French, and English until the first permanent English colony was established at Jamestown in 1607, when the confederacy numbered about 14,000–21,000 people. At that time, there were more than 30 tribes in the Algonquian Powhatan Confederacy, of which the Pamunkey were the largest and one of the most powerful. They inhabited the coastal tidewater of Virginia on the north side of the James River near Chesapeake Bay. Chief Powhatan and his daughter Pocahontas were of the Pamunkey Indians.

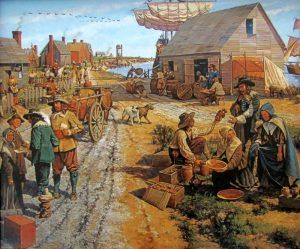

The first English settlement at Jamestown had a complicated relationship with Virginia’s tribes. In the winter of 1607, Opechancanough, chief of the Pamunkey tribe, captured Captain John Smith and brought him to his brother, Chief Powhatan. This first meeting between Powhatan and Smith resulted in an alliance. Powhatan sent Smith back to Jamestown in the spring of 1608 and started sending gifts of food to the colonists. Without Powhatan’s donations, the settlers would not have survived the first winters.

Though the colonists respected Powhatan, they characterized other American Indians by terms such as “naked devils.” The colonists generally mistrusted most Indian tribes, but they noted the Pamunkey did not steal.

“It pleased God, after a while, to send those people who were our mortal enemies to relieve us with victuals, such as bread, corn, fish, and flesh in great plenty, which was the setting up of our feeble men. Otherwise, we had all perished.”

— George Percy, one of the original Jamestown settlers.

As the settlement expanded, competition for land and other resources and conflict between the European settlers and Virginia tribes increased.

Powhatan’s maternal half-brother and ultimate successor, Opechancanough, launched attacks in 1622 and 1644 due to English colonists encroaching on Powhatan lands. The first, known as the Indian massacre of 1622, destroyed colonial settlements such as Henricus and Wolstenholme Towne and nearly wiped out the colony. Jamestown was spared in the attack of 1622 due to a warning. During each attack, about 350-400 settlers were killed. In 1622, the population had been 1,200, and in 1644, 8,000 before the attacks. Captured in 1646, Opechancanough was killed by a settler assigned to guard him against orders. His death contributed to the decline of the Powhatan chiefdom.

The first treaty between Opechancanough’s successor, Necotowance, and the English was signed in 1646. The treaty set boundaries between lands for the Virginia tribes and those considered property of English colonists, reservation lands, and yearly tribute payments of fish and game to the English. Perhaps the oldest inhabited Indian reservation in North America, the 1,600-acre reservation is on the Pamunkey River in King William County.

Bacon’s Rebellion began in 1675, attacking several tribes loyal to the English. The Rebellion was a joint effort of white and black former indentured servants. Nathaniel Bacon led the Rebellion against his relation, Governor Sir William Berkeley because he refused to come to the aid of colonists subjected to frequent raids and murders by the Indians. Bacon and other colonists, former indentured servants, were victims of raids by local Virginia tribes. Bacon’s overseer was murdered by raiding Indians.

Cockacoeske, who succeeded her husband after he was killed fighting for the English, was an ally of Berkeley against Bacon. The Pamunkey practice of matrilineal succession created some confusion for Englishmen, who finally, after she signed the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation, recognized the “Queen of the Pamunkey” after Bacon’s Rebellion ended. More tribal leaders signed this treaty than in 1646. It reinforced the annual tribute payments and added the Siouan and Iroquoian tribes to the Tributary Indians of the colonial government. More reservation lands were established for the tribes, but the treaty required Virginia’s tribal leaders to acknowledge they and their peoples were subjects of the King of England. While the Rebellion did not wholly succeed in the initial goal of driving the American Indians away from Virginia, it did result in Governor Sir William Berkeley being recalled to England, where he died shortly thereafter.

The treaty gave Queen Cockacoeske authority over the Rappahannock and Chickahominy tribes, which had not previously been under the paramount chiefdom of the Pamunkey. Completing the treaty ushered in a time of peace between the Virginia tribes and the English Colonists.

As with other tribes in the Powhatan Confederacy, the Pamunkey also had a chief and a tribal council composed of seven members, elected every four years. The chief and council executed all the tribal governmental functions set forth by their laws. In 1896, a study noted that tribal laws concerned controlling land use, stealing, and fighting. Instead of using corporal punishment, incarceration, or chastisement, anyone who broke a tribal law was fined or banished.

Tribal laws govern all civil matters. In criminal matters, outside authorities, such as a Sheriff or Police, may respectfully notify the Tribal Chief about serving a warrant. But, such action is not legally required. The tribe does not operate a police force or jail. Most tribal members obey the tribal laws out of respect for the chief and the council. The tribe discourages verbal attacks against members and has strict slander laws.

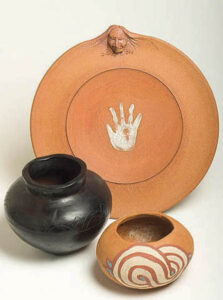

The chief paid an annual tribute to Virginia’s governor, consisting of a game, usually a deer, pottery, or a peace pipe. The Pamunkey have been paying such tribute since the treaty of 1646, and the practice continues today.

The Pamunkey Indian School House was established as a one-room schoolhouse on May 22, 1909. Before 1909, Pamunkey children attended school in a log cabin at the Reservation entrance. The school served students from 1st through 7th grade. Students wishing to continue schooling beyond 7th grade were forced to attend a Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools, including Bacone College in Oklahoma, Haskell Institute in Kansas, or Cherokee High School in North Carolina.

The Pamunkey tradition of pottery-making dates back to before the English settled Jamestown. People have been using clay from the banks of the Pamunkey River since prehistoric times, and many continue to use traditional methods.

By the 1930s, during the Great Depression, most Pamunkey Indians depended on non-salaried labor, including fishing, hunting, and farming. In 1932, the Commonwealth of Virginia helped the Pamunkey develop their pottery as a source of income. The state set up a pottery school program, provided a teacher, and furnished materials for a building the tribe erected. Tribal members learned methods to increase the speed of manufacture, incorporating firing pottery in a kiln and using glazes into their techniques. They also incorporated designs and pictographs based on well-known and popular Southwestern Indigenous traditions. Other pictographs represented important stories of the tribe, such as the story of Pocahontas and the story of the treaty that set up payments of game. Today, the Pamunkey use traditional and newer techniques to create their pieces.

In 1948, the Pamunkey School was closed due to low attendance, and the remaining children were transferred to the Mattaponi Reservation School.

In 1979, with help from a federal grant, the Pamunkey tribe opened the Pamunkey Indian Museum. Resembling the traditional yehakin, the museum provides visitors insight into the tribe’s long history and culture. It displays artifacts from more than 10,000 years of Indigenous settlement, replicas of prehistoric materials, and tribal history. The museum also displays a variety of Pamunkey pottery, describing the differences in construction methods, types of temper, and decorating techniques.

On March 25, 1983, a joint resolution formally recognized the Pamunkey Tribe and the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Mattaponi, Rappahannock, and Upper Mattaponi tribes. The Nansemond and Monacan tribes were recognized in 1985 and 1989, respectively.

Though the Commonwealth of Virginia has always recognized the Pamunkey tribe, with formal relations dating back to the treaties of 1646 and 1677, the Federal Government did not. Since the United States did not exist during those treaties, no formal relations existed between the Pamunkey and the federal government. In 1982, the Pamunkey began the process of applying for federal recognition. Their formal application met with opposition from MGM Casinos, which feared potential competition with its planned casino in Prince George’s County, Maryland, and from members of the Congressional Black Caucus, who noted that the tribe had historically forbidden intermarriage between its members and black people. The interracial marriage ban, which had long been unenforced and was formally rescinded in 2012, was a relic of the tribe’s attempt to circumvent Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which recognized only “White” and “Colored” people. The Bureau of Indian Affairs formally recognized them on July 2, 2015, stating, “The Pamunkey Indian Tribe has occupied a land base in southeastern King William County, Virginia—shown on a 1770 map as ‘Indian Town’—since the Colonial Era in the 1600s.” Federally recognized Indian tribes receive access to services from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, including medical, housing, and educational benefits.

Withstanding pressure to give up their reservation lands has helped them maintain traditional ways. Men still use some old fishing methods and continue hunting and trapping on reservation lands.

The tribe has over 400 members today.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See:

Chief Powhatan – Wahunsunacawh

Sources:

Pamunkey Tribe

Pollard, Jno. Garland. Pamunkey Indians of Virginia. Bureau of Ethnology, Government Printing Office. 1894.

Secretary of the Commonwealth of Virginia

Speck, Frank Gouldsmith. Chapters on the ethnology of the Powhatan tribes of Virginia. Editor: Hodge, F. W. Heye Foundation, Museum of the American Indian,1928.

Wikipedia