California Republic

By Ella M. Sexton, 1903

The Missions were at their best while Spain owned Mexico and the two Californias — the U.S. state of California and the Mexican states of Baja California and Baja California Sur. They grew rich in stores of grain, cattle, and horses. Almost all the people were Spanish or Indians, and they lived at the Missions or on nearby ranches. However, when Mexico refused to be ruled by Spain in 1822, Alta or Upper California became a Mexican territory and, later, a republic with governors sent from Mexico. The Mission priests did not like the change and thought Spain should still own the New World. Before long, it was ordered that the Missions should be turned into pueblos or towns and that the priests were no longer to make slaves of the Indians. The missionaries were to stay as priests and teach the Indians in schools, but the Mission lands were to be divided so that each Indian family could cultivate a small farm. From that time, the Missions began to decay and were finally given up to ruin.

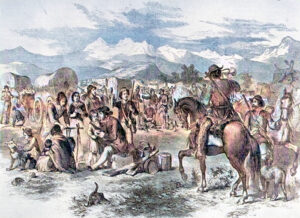

Then Americans began coming in, the first group of hunters and trappers traveling from Salt Lake City, Utah, to the San Gabriel Mission. All kept talking about the rich country where farming was so easy, and they wished to have land. However, the Mexicans and the native Californians did not believe in allowing the Americans, as they called all the people from the Eastern states, to take up their farming lands and hunt and trap the wild animals. So, there was much quarreling. But the Americans poured in, got land grants, and built houses.

In 1836, though Alta California declared itself a free state and no longer looked to Mexico for support, Mexican rule continued. The United States had wanted California for a long time and had tried to buy it from Mexico. The fine bay and harbor of San Francisco, known to be the best along the coast, was especially needed by the United States to shelter or repair ships on their way to the Oregon settlements. England also wanted this bay, but the Californians tried to keep everyone out of their country.

Among the Americans who came overland and across the Rocky Mountains about this time was John C. Fremont, a surveyor and engineer called the “Pathfinder.” On his third trip to the Pacific Coast in 1846, he wished to spend the winter near Monterey with his 60 hunters and mountaineers. Jose Castro, the Mexican general, ordered him to leave the country at once, but Fremont answered by raising the American flag over his camp. As Castro had more men, Fremont did not think it wise to fight but marched away, intending to go north to Oregon. He returned to the Klamath country because of snow and Indians and camped where the Feather River joins the Sacramento. It is almost certain that Fremont wished to provoke Castro and the Californians into war and capture the country for the United States.

A party of Fremont’s men rode down to Sonoma, where there was a Mission and a presidio with a few cannons in charge of General Mariano Vallejo. These men captured the place and sent Vallejo and three other prisoners back to Fremont’s camp. Then, the independent Americans decided to have a new republic and a flag. So, they made the famous “Bear flag” of white cloth, with a strip of red flannel sewed on the lower edge, and on the white, they painted in red a large star and a grizzly bear, and also the words “California Republic.” They then raised the flag over the Bear-flag Republic. Many Americans joined their party, but the stars and stripes replaced the bear flag when the American flag went up at Monterey.

At this time, the United States and Mexico were at war because of Texas, and Commodore John D. Sloat oversaw the warships on the Pacific Coast. The commodore had been told to take Alta California, if possible, so, sailing to Monterey, he raised the stars and stripes there in July 1846 and ended Mexican power forever. The American flag flew at the San Francisco Presidio two days later and at Sonoma, Sutter’s Fort, or wherever there were Americans. The flag was greeted with cheers and delight. Then Commodore Sloat turned the naval force over to Commodore R.F. Stockton and returned home, leaving all quiet north of Santa Barbara.

Commodore Stockton sent Fremont and his men to San Diego and, taking 400 soldiers, went to Los Angeles. The native Californians and Mexicans were determined to fight against the United States rule. General Castro, his men, and Governor Pio Pico, the last Mexican governor, were driven out of the country. Stockton then declared that Upper and Lower California were to be known as the “Territory of California.”

In less than a month, however, the Californians in the south gathered their forces again and took Los Angeles. General Stephen Kearny was sent out with the “Army of the West” to assist Fremont and Stockton in settling the trouble. Peace was declared after several battles, and Kearny acted as governor of the new territory, displacing Fremont. At last, by the treaty that closed the Mexican war in 1848, Alta California became the property of the United States, and Lower California was left to Mexico.

Army of the West.

From that time, there was peace, and before long, the discovery of gold made the new territory very important. The rush to the gold mines brought thousands of men, and as no government had been provided for the territory, Governor Riley called a convention in 1849 to form a government plan.

This Constitutional Convention of delegates from each of California’s towns met in Monterey. The constitution they drafted lasted 30 years; under it, California was built up. It declared that no slavery should ever be allowed here and settled the present eastern boundary line.

Governor Bennet Riley set the first Thanksgiving Day for the territory in 1849. The first governor elected by California voters was Peter Burnett, and Fremont and Gwin were chosen as senators in the first legislature. Congress finally admitted California into the Union by passing the California bill that President Millard Fillmore signed on September 9, 1850.

By Ella M. Sexton; Stories of California, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1903. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2025.

Also See:

The History of the Sovereign States of America