Boston, Massachusetts, had a prominent role in helping Black Americans flee enslavement in the South via the Underground Railroad.

The Underground Railroad was a pivotal effort to help individuals in bondage in North America escape from slavery. While many runaways began their journeys without assistance and some managed to self-emancipate on their own, each decade that slavery was legal in the United States saw an increasing public awareness of a secretive network and a growing number of people willing to aid runaways. This organization comprised a series of safe houses that stretched from the southern states to Canada, providing shelter and protection for runaway slaves seeking freedom in the North.

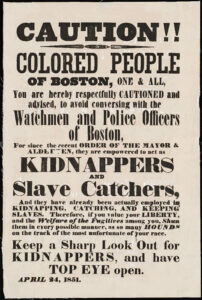

Although slavery was illegal in northern states, the Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1793 and 1850 made it legal for slave hunters to travel to free states and capture runaway slaves. Some slaves took their chances and settled in free states, but many others passed through as they headed for Canada where slavery was illegal and slave hunters could not enter.

As the capital and largest city of one of the earliest states to abolish slavery, Boston became a key destination for many people escaping slavery through the Underground Railroad. As a port city, it offered a vital route for escape, with most freedom seekers arriving by sea as stowaways on ships departing from southern ports. Boston’s close-knit, free Black community, which worked along the harbor, played a crucial role in assisting those who arrived in the city. They provided essential communication and a welcoming sanctuary for these individuals. In their community, located on the north slope of Beacon Hill, Black Bostonians opened their homes and churches to those escaping on the Underground Railroad.

Through their collective resistance and direct action, Black Bostonians and their allies continued to shelter and assist hundreds of freedom seekers throughout the Fugitive Slave Law years. They tirelessly and selflessly acted upon their resolution that “eternal vigilance is the price of liberty, and that they who would be free, themselves must strike the blow.” In doing so, they transformed Boston into an integral hub on the Underground Railroad’s network to freedom.

Faneuil Hall, widely recognized for its significance as a site of colonial protest during the American Revolution, served as an important gathering place for public dissent against slavery and the country’s fugitive slave laws. Cherished as the “Cradle of Liberty,” Faneuil Hall played an integral role in Boston’s Underground Railroad network.

Beginning in the late 1830s, Boston’s abolitionists regularly used Faneuil Hall to host their meetings and rallies. These gatherings were often called in response to high-profile fugitive slave cases. The abolitionists not only protested the arrests of fugitive slaves but also actively organized against the fugitive slave laws. Through protests and petitions, they pressured state and local officials to resist the enforcement of these federal laws. Additionally, they formed vigilance committees to assist those seeking freedom on the Underground Railroad, encouraging supporters to help those in need and to thwart slave catchers.

In 1842, George Latimer escaped from slavery in Virginia and came to Boston seeking his freedom. His arrest under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 prompted significant protests throughout the city. On October 30, 1842, abolitionists gathered in Faneuil Hall to express their outrage and inspire action against Latimer’s arrest. They resolved that “this meeting protests…against the deliverance of George Latimer, into the hands of his pursuers” and that Massachusetts is “solemnly bound to give succor and protection to all who may escape from the prison-house of bondage, and flee to her for safety.”

They further declared that:

“If the soul-traders and slave-drivers of the South imagine that Massachusetts is slave-hunting ground, on which they may run down their prey with impunity… they will find themselves mistaken.”

Though Bostonians quickly purchased Latimer’s freedom, his case galvanized the abolitionist community of Massachusetts into further political action. They soon gathered over 64,000 signatures on a petition presented to the Massachusetts legislature. This petition resulted in the passage of the 1843 Personal Liberty Act, which “forbade Massachusetts officials or facilities from being used in the apprehension of fugitive slaves and represented a major victory for abolitionist forces.”

In 1846, another fugitive slave case rocked Boston, prompting an even larger protest at Faneuil Hall. The case involved a freedom seeker known as George, who escaped slavery from Louisiana by stowing himself on a Boston-bound ship. When he was discovered onboard, the ship’s captain had George confined, and despite local abolitionists’ efforts, he was sent back to the South. Bostonians, roused by this case, gathered at Faneuil Hall. The Liberator, Boston’s major abolitionist newspaper, reported on this “Great Faneuil Hall Meeting for the Prevention of Illegal Seizures of Slaves.” Presided over by former president John Quincy Adams, this meeting reportedly drew 5,000 people and culminated with the appointment of a Vigilance Committee to protect those illegally arrested as fugitives. This 1846 Vigilance Committee encouraged its members to “avoid giving slave catchers any ‘aid or counsel’ while offering ‘comfort and help to any fugitive slaves who may be thrown upon our hospitality.”

With the passage of the new Fugitive Slave Law on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850, Boston’s abolitionist community grew increasingly militant in their Underground Railroad activity. The act required that slaves be returned to their owners, even if they were in a free state.

This hated law strengthened the earlier fugitive slave laws by engaging federal marshals as slave catchers, imposing high fines and imprisonment for those who helped a fugitive, and mandating that state and local authorities, as well as citizens, assist in executing this law.

Black activists met at the African Meeting House on October 5, 1850, to plan their collective response. This group included William Cooper Nell and Lewis Hayden, two of Boston’s most prominent underground railroad operatives. William Craft, who escaped slavery with his wife Ellen, also participated in this meeting and served as its Vice-President. These community activists promised a sustained fight against the federal government and militant resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law. When slave catchers soon came looking for the Crafts, these abolitionists put their words into action and succeeded in thwarting the attempt to capture the famous fugitive couple.

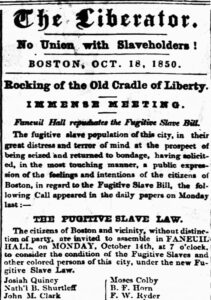

With the passage of the new, harsher Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Bostonians once again flocked to Faneuil Hall in protest. The Liberator reported, “Rocking the Old Cradle of Liberty—Immense Meeting—Faneuil Hall repudiates the Fugitive Slave Bill.” The meeting drew thousands of people to Faneuil Hall. The prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had escaped slavery years before, riled the crowd with his warning…

If you are… prepared to see the streets of Boston flowing with innocent blood, if you are prepared to see sufferings such as perhaps no country ever before witnessed, give in your adhesion to the fugitive slave bill – you, who live on the street where the blood first spouted in defense of freedom. The slave hunter will be here to bear the chained slave back, or he will be murdered in your streets.

At this meeting, the abolitionists asserted that “our moral sense revolts against the new Fugitive Slave Law, believing it to involve the height of injustice and inhumanity” and pledged:

To our colored fellow citizens who may be endangered by this law all of the aid, co-operation, and relief…and we accordingly advise fugitive slaves and other colored inhabitants of this city and vicinity to remain with us… We have no fear that anyone will be returned to the land of bondage.

Attendees at this meeting formed a new Committee of Vigilance and Safety to “take all measures that they shall deem expedient to protect the colored people of this city in the enjoyment of their lives and liberties…” This Vigilance Committee provided valuable assistance to those escaping slavery through Boston in the form of shelter, clothing, money, legal aid, medical attention, and passage further north for the duration of the Fugitive Slave Law years.

In 1851, Black Bostonians rescued Shadrach Minkins in a brazen daytime assault on the courthouse. Not all efforts succeeded, however, as authorities foiled the plot to rescue Thomas Sims in 1851.

Faneuil Hall also played a prominent role in Boston’s most infamous fugitive slave case. On May 26, 1854, thousands gathered at Faneuil Hall to protest the capture of Anthony Burns, who escaped from Virginia. Arrested under the Fugitive Slave Law, authorities held Burns captive at the nearby courthouse. As the meeting continued, someone interrupted by shouting, “A crowd of negroes is storming the courthouse.” While some of the meeting’s organizers called for restraint, others flooded out of Faneuil Hall to help in the attempted courthouse rescue. Unfortunately for Burns, the rescue attempt failed, and Bostonians watched in protest as a military force escorted him back to slavery in the days ahead. However, within nine months, Bostonians raised the funds and purchased Anthony Burns’ freedom, and he returned north a free man.

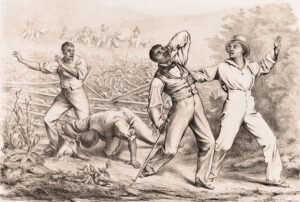

In addition to protesting the fugitive slave laws and providing shelter and assistance to freedom seekers, some Bostonians engaged in daring rescue attempts of those arrested by the slave catchers.

By the mid-1850s, public opinion began to shift, even among previous supporters of the Fugitive Slave Law. The Burns case inspired a state-wide petition leading to the passage of a stringent new Personal Liberties Law in 1855. Although the Fugitive Slave Law remained in effect until the Civil War, this new Personal Liberties Law made it nearly impossible to publicly return another freedom seeker from the free soil of Massachusetts.

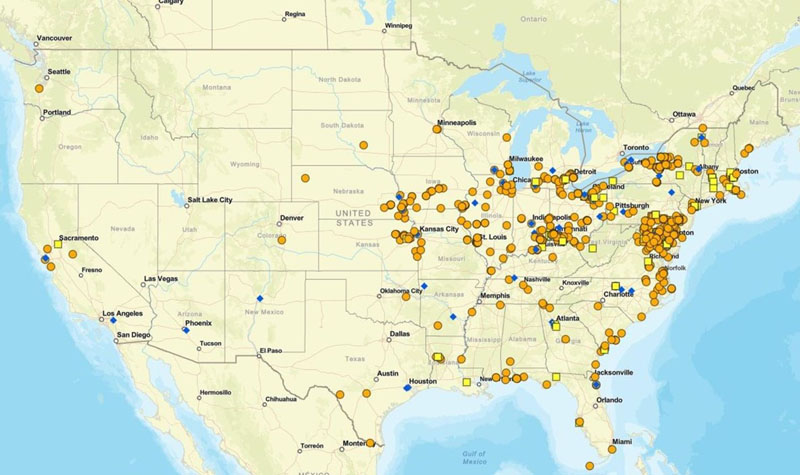

The National Park Service established a program in 1998 dedicated to identifying and preserving underground railroad sites. Locations related to the Underground Railroad are part of the Network to Freedom program, which includes over 800 locations nationwide, including National Park units and locations with a verifiable connection to the Underground Railroad.