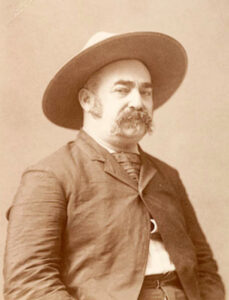

John X. Beidler, who became known as “Vigilante X”, was a Montana Vigilante and Deputy U.S. Marshal.

Beidler was born on August 14, 1831, in Mount Joy, Pennsylvania, to John and Anna Hoke Beidler. He was raised in Chambersburg, where he attended school for a brief time and worked as a shoemaker and a brickmaker.

His father died in 1849, and his mother died in about 1850. Afterward, he made his way west, first locating in Illinois before landing in Kansas, where he worked on a small farm. During this time, he became friends with the abolitionist John Brown and joined with other “free-soilers” in attacking border ruffians during the days of Bleeding Kansas. As one of John Brown’s followers, he received a wound in the leg in one of those skirmishes that left him a cripple for the rest of his days.

Following Brown’s death by hanging for his part in the raid on Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, John left Kansas for Texas.

From Texas, he moved on to Colorado. When he heard the news of gold strikes in Montana Territory, he headed northward in 1863, arriving in Virginia City on June 10, just days after a group of miners made the discovery. During these transient times, he worked in several positions, including store clerk, prospector, pack train operator, and freighter.

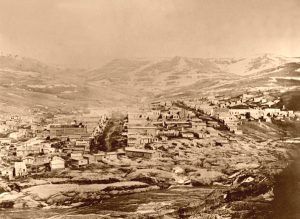

During that time, very little formal law enforcement existed in the boom towns that sprang up, and Virginia City was no exception. Informal minor’s court proceedings handled minor legal matters, but there was no official law enforcement for significant crimes such as looting, robbery, and murder. One gang, called the Innocents, was led by Henry Plummer, who was also the sheriff in nearby Bannack.

He worked as a stagecoach shotgun guard and soon joined the Montana Vigilantes to help control the lawless territory. After joining the Vigilantes, Beidler became one of its most active members and, in December of 1863, swore a secret oath along with 24 men. Their mission was to hunt down, capture, and hang as many criminals as possible and suppress the gang of road agents and robbers.

Before the formation of the vigilance committee, one man, George Ives, received a jury trial after he was accused of murdering Nicholas Tbalt, a young man whose parents had been killed by Indians. During the trial, Beidler stood guard over the proceedings. After Ives was convicted following a three-day trial, he pleaded for a stay of execution. From the rooftop above the proceedings, Beidler shouted out to the prosecutor, “Ask him how much time he gave the Dutchman!” George Ives was hanged that evening.

The Vigilantes believed that the only way to restore law and order was to eliminate gangs and outlaws from the area. Enthusiastic in this role, he quickly became the group’s chief hangman and participated in several executions.

As the face of the Vigilantes, Beidler, or “Vigilante X,” as he liked to be called, was accused of stepping over the line. Some lauded him as trustworthy and fearless, while others believed he was nothing more than a “pint-size bully” and braggart. With a complex personality, he was an energetic little man, shorter than his rifle at five-foot-three. Described as exceedingly impatient, he admitted that his temper often became “boiling.”

As a “reward” for his work on the Vigilante Committee, he was appointed Customs Collector and U.S. Deputy Marshal. However, he continued his vigilante activities, which led many to accuse him of overstepping the bounds of established law and justice. In January and February of 1864, 21 men were captured and hanged – no trials, no appeals, and no time to put one’s affairs in order.

While serving as a law enforcement official, he simultaneously helped to organize a vigilance committee in Helena.

By 1867, he found plenty of work in Helena, which was infested with a criminal element – practically every day, there were reports of robberies and murders.

In 1870, his penchant for crossing the line almost resulted in his being arrested for murder. In January, a Chinese miner by the name of Ah Chow had killed a man in Helena. When Beidler captured the Chinaman, he returned his prisoner to Helena and turned him over to the vigilantes, who promptly hanged him. Beidler applied for Chow’s bounty, which raised the ire of the local newspaper’s editor:

“We could not believe that any mere private citizens would engage in so lawless a proceeding and then have the temerity to acknowledge his guilt by applying for and receiving the reward.”

Beidler claimed that he was thereafter threatened, allegedly receiving a note warning him, “We… will give you no more time to prepare for death than the many men you have murdered… We shall live to see you buried beside the poor Chinaman you murdered.”

John Beidler continued to serve as deputy U.S. Marshal until the late 1880s. In 1888, his health began to fail, and, being destitute, he relied on the charity of friends.

On January 22, 1890, he died at the Pacific Hotel in Helena from complications of pneumonia at the age of 58. Hundreds of friends and associates attended his funeral, which was paid for by contributions. He was buried in Helena. The Great Falls Weekly Tribune summed up his life:

“He dies poor, having served his territory much better than he served himself. Peace to his ashes.”

On October 21, 1903, his body was exhumed by the Montana Society of Pioneers and moved to Forestvale Cemetery. A rough boulder, emblematic of his rugged character, was later erected over his grave and inscribed with a plaque:

Even though he was known for his “extra-legal” vigilante activities, apparently, the historical society and the annals of Montana history have chosen to honor him regardless. He was definitely one of a kind.

Sheriff Henry Plummer was hanged from the very

gallows that he, himself, had built earlier in the year.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Find-a-Grave

Thrapp, Dan L.; Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography, University of Nebraska Press, June 1, 1991.

WikiTree