By Colonel Theodore Ayrault Dodge in 1891

The cowboy is in the saddle more than any man on the Plains. He rides what is well known as the cowboy’s saddle, or Brazos tree. It is adapted from the old Spanish saddle — is, in fact, almost similar — and differs sensibly from the Mexican. The line of its seat from cantle to horn, viewed sidewise, is a semicircle; there is no fiat place to sit on. This shape gives the cowboy, seen from the side, all but as perpendicular a seat in the saddle as the old knight in armor. There are, of course, other saddles in use. The Texas saddle has a much flatter seat than the Brazos tree; the Cheyenne saddle is still flatter, with a high cantle and a different cut of pommel arch and bearing; some individuals may ride any peculiar saddle. But all must have the horn and high cantle. The cowboy would be at home or fit for service in no other tree.

The cowboy is careful of his ponies, not only because of a horseman’s motives but because he is held accountable for them. Unlike the Indian, he rarely has a sore-backed nag. He often uses a gunny-bag saddle cloth next to the pony’s skin — the hempen fiber of which keeps the back cool — and over this, for padding, his woolen blanket.

In the Southwest, he is apt to sport a variegated saddle cloth with fringed edges, such as the Mexicans parade, and if he can manage to get hold of a Navajo blanket, he is fixed. These wonderful bits of bright, pleasing colors of handwork are worth $50 upward, never seem to wear out, and are by long odds the best thing under a saddle that exists. The Indian will give from two ponies upward for one of them when he can buy a wife for one pony, and not a very good pony (or wife) at that. The cowboy’s saddle is held in place by one very wide or two narrower hair cinches, though the single cinch is more a Californian habit. If one is on the Plains, always put a full hand breadth back of the girth-place in the East. The rear girth gets a purchase on the back slope of the ribs.

The cowboy’s bit is any curb with a long gag. He rides under all conditions with a loose rein, the bit ends of which are of chain, which clanks a rhythmic jingle to his easy lope. His pony is as surefooted as a mountain goat and will safely scramble with his big load up a cliff or slide down a bank, which would make our tenderfoot’s hair stand on end. The loose rein and the sharp gag enable the cowboy with the least jerk to pull his pony back on his haunches, for the pony is unused to a steady hold. The cowboy is not a three-legged rider. The bit hangs in a fancy trade bridle, which the cowboy ornaments in various fashions to suit his own ideas of style. The effect of its use on the pony is precisely the reverse of that which is made by a bit on a horse supplied by school methods or even bitted and which has been ridden on a light touch. The latter brings down his head to the hand, with an arched neck, easy mouth, and a give-and-take feel of the hand. At the least intimation of the bit, the pony, long before the rein is taut, jerks up his head and must have a tough mouth or an exceptional fright to make him take hold of you.

The cowboy’s bit is any curb with a long gag. He rides under all conditions with a loose rein, the bit ends of which are of chain, which clanks a rhythmic jingle to his easy lope. His pony is as surefooted as a mountain goat and will safely scramble with his big load up a cliff or slide down a bank, which would make our tenderfoot’s hair stand on end. The loose rein and the sharp gag enable the cowboy with the least jerk to pull his pony back on his haunches, for the pony is unused to a steady hold. The cowboy is not a three-legged rider. The bit hangs in a fancy trade bridle, which the cowboy ornaments in various fashions to suit his own ideas of style. The effect of its use on the pony is precisely the reverse of that which is made by a bit on a horse supplied by school methods or even bitted and which has been ridden on a light touch. The latter brings down his head to the hand, with an arched neck, easy mouth, and a give-and-take feel of the hand. At the least intimation of the bit, the pony, long before the rein is taut, jerks up his head and must have a tough mouth or an exceptional fright to make him take hold of you.

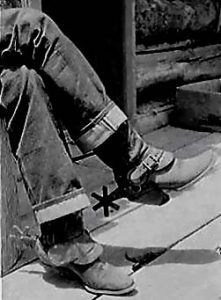

The most striking part of the cowboy’s rig is the chaperajos or huge leather overalls he is apt to wear. These originated in the mesquite or chaparral country, where the cattle business had its on-gill, and where jeans or a pair of the best cords will be torn to shreds in a day.

When chaperajos are seen out of this region, they are retained by the force of habit. This singular garment is made of cowhide, weighs five or six pounds, and is used invariably to have the edge cut into a long fringe, but this ornamentation has begun to disappear. It boasts no seat, which could with difficulty be made to fit. On the left leg of the chaperajos is a pocket for cigarettes or chewing tobacco, matches, and small sundries. The chaperajos could not comfortably be worn in any other saddle than one that gave a short, upright, “forked-radish” seat.

They are too much like trousers made of stovepipe.

The cowboy’s saddle bow usually hangs a rawhide, hair, or Mexican grass rope from 40 feet long upward for every purpose, from roping cattle to hauling out a mired team. His rifle, a seventy-three Winchester, rests crosswise at the horn in a broad pouch-like strap, which protects the lock from injury or is slung under the left leg, where it can lie with equal security. He boasts few riches. What he has is apt to be in dollars or occasionally a few steers. He buys a pair of eighteen-dollar boots and a pair of $15 gloves, and the rest of his rig and dress is scarcely worth a five-dollar bill.

Broncos with manners are like angels’ visits. The cowboy’s bronco is never what we should call half-broken. By the time he has been ridden enough to be well broken in, a lie is usually all broken up. He is a difficult fellow to mount, being ridden but once every four or five days. One could never mount him without assistance if he were not so small. He will back away, plunge forward, swerve, kick, strike, squeal, rush full at you with mouth wide open, or perform a hundred other antics that would compel us simple-minded park riders to hurry him off to the nearest auction room. He is, in fact, what we are wont to characterize as a “dangerous brute.”

But the cowboy can always see him and get him one better. He approaches him at the left shoulder and gathers the rein in his left hand. Not infrequently he puts his hand over the pony’s eye while he grabs the left stirrup and gets his foot in it, following up the broncos antics as best he may.

Then, grabbing the pommel with the right hand and the pony’s withers with the left, and if possible, getting his left elbow in the hollow of the neck just forward of the withers, nothing which the pony can do can keep him out of the saddle. In fact, a plunge that drags him from his feet will all the more certainly swing him to his seat. Then, after a series of bucks, more or less severe, during which his spurs go time and again into the pony’s flanks, the mastery is established where it properly belongs, and harmony, such as it is, reigns till the next time of mounting.

The cowboy universally rides a lope, as do all people who use wild horses. The bronco has no other gait, in fact, unless a sort of fox-trot. The cowboy’s seat is unsuited to an open trot. He won’t ride it if he can help it, and, it may as well be confessed, he cannot — and no one can – sit close without pounding to the long rangy trot of a big thoroughbred though it is the perfection of gaits if you rise to it. We hear from many that the cowboy can do everything. Rumors run that some of Buffalo Bill’s cowboys rode English horses in their own saddles and beat everything to hounds in the midland counties. Those who know that country and its riders accept this statement cum grano [with a grain of salt.] But assume its truth. One often sees a dare-devil of an English lad just out of college who imagines, because he has once or twice led the field on one of the squire-a crack hunters, that he is the best rider in it. But, in truth, he is risking his horses, not to count his own neck, at every obstacle he clears, and pumping the last ounce out of his generous beas, while wiser and older riders close behind him are saving their horse, and bringing them in fresh and able. It is not riding a fabulous distance, or at the greatest speed, or with the most conspicuous daring, which is the test, but getting in at the death with the least exertion to man and beast. The highest proof of artistic horsemanship is to accomplish your task with the least expenditure of physical force. To keep the horse in good condition is, among civilized people, a more significant test than the speed or daring of the rider. So, in the great distance tests made by Plain’s ponies and civilized horses, one element is apt to be forgotten. The latter must be brought in without injury; the feat may kill the pony. No question is that if the pony and the thoroughbred, under even conditions, are ridden until both fall in their tracks, the pony will be beaten in speed and distance.

But the cowboy is unequaled in his own province, and this is enough of fame. His seat is astonishing. It is a common feat for him to put a playing card on the saddle, a dollar piece under each foot in the stirrup, or under his knees and ride a vigorous bucker. Still, he cannot ride a flat saddle until he learns its trick. And while no cowboy, without serving his apprenticeship in the hunting field, would hold his own with practiced riders there, certainly, he would much sooner learn to ride across the country well than even the best of cross-country men could vie with him in controlling a vicious bronco, or, indeed, in riding over the rough country he is wont to cover. It is the universal experience of the Plains that the best English rider fights shy of ground which the cowboy will gallop over until he catches on to it, and confides in the sure feet of his little mount. Some men never learn to ride, but it stands to reason, ceteris paribus, that the man who makes riding his business will be a stouter horseman rather than one to whom it is a mere diversion.

As a rough rider, the cowboy is facile princeps [easily the best]; as a horse-breaker, he devotes too little time to his task, nor does he go to work in the way best calculated to produce a quiet nag. Bronco busting is a distinct art. The bronco buster may be a professional who has taken initially up the work to replenish his exchequer, depleted by whiskey and poker, and sticks to it for lack of an easier jo, and because he is at a low-water mark, or he may be a cow-puncher in slack times. As a rule, he cannot stick it out very long, for the business is sure to end by busting the buster. It is unquestionably the most violent form of athletics, and the bronco buster, though he must be strong and active, is not, as a rule, in the exceptional condition necessary for great feats of strength and endurance. Indeed, training would scarcely help him much. Whatever his strength and health, the bronco buster is sure to get hurt sooner or later. He works it off and on at ten dollars a bronco. All cowboys do more or less breaking, and some ranches always break their own ponies and generally have better ones for so doing.

The typical bronco buster should weigh 170 to 180 pounds. Weight does the business when a light man can accomplish nothing, though one of the most successful bronco riders of whom the writer ever heard was a long-geared, lank Texas lad who would stick to his horse till his head would snap like a whip with the bucking, and he himself lose consciousness. Indeed, it is not uncommon for violent bucking to produce hemorrhage of the lungs. Few cowboys, but they get hurt one way or another at intervals. No creature in the service of man can put his master to such violent efforts in his subjugation as the bronco. Of course, a better plan would be the more gradual one of civilized trainers, but there is no time for this.

The secret of “busting” (the word is advisedly used, as picturesquely expressive of the process, in contradistinction to breaking) lies in completely exhausting the bronco at the first lesson; he will never buck for keeps more than once. Buffalo Bill’s ponies have been allowed to throw their riders, or the rider has judiciously slipped off at the right intervals, thus impressing the idea on the broncos intelligence that he can surely throw his man if he sticks long enough to his bucking. But once ridden to the verge of falling in his tracks, the pony will not do his level worst again but content himself with grunting and yelling, knocking his teeth out, and playing the devil generally. The buster must be careful to keep well away from sheds and timber and have room enough to cut a wide swath.

He must be able to stick to his saddle like a leech, with or without stirrups. If he needs his stirrups for a hold, he is not looked on as much of a rider, and it is a matter of pride with the sure enough buster not to rely on anything but what old horsemen call glue. He will ply the quirt at every jump to show his contempt for the broncos power. It is a fair fight and no favor between man and beast.

But the buster has been there before and knows exactly what he is about; the bronco is new to the business, and though he invariably makes a good fight, he will surely have to give in. Some ponies take more busting than others, and some always buck more or less, however well broken. When the punchers turn out on a cold morning, the ponies will buck through the entire outfit, and the crowd stands around to see each man mount, watch the fun, and chaff the rider.

Two rides will usually bust a bronco so the average cow-puncher can use him, but he would scarcely keep company along with most Central Park riders. Two men generally work together. They enter the corral, where there is apt to be a good bunch of ponies, and these, as if guessing what is to come, at once jump away and go careering madly around the enclosure. One man handles the rope, which he trails along the ground until he selects his pony and then drags it over his head with a sudden and dexterous snap.

A good roper can cast twenty-five feet. Then both men seize hold, dig their heels into the ground to stop the pony — knack will enable even one man to jerk him up if need be — and finally, get a turn round the snubbing post in the center of the corral. There, they have the pony fast and gradually work him up to it. But the pony does not submit to this vigorous coaxing in an amiable mood. He bucks and plunges, kicks, squeals, and charges straight at his tormentors, who have to play a regular game of hide-and-seek behind the snubbing post to save them from broken bones.

Finally, the men get the winded pony snubbed up close to the post, where one can hold him while the other gets behind him and catches another rope on a forward foot. Then, as the pony starts, he yanks the foot back, and in nine cases out of ten, down goes the pony. But not always. Some obstinate ones will sink on the other knee and, with the nose on the ground, still have four points to stand on. But by and by, he must; the snubbing rope is made fast, the saddle is fitted on tant bien que mal [as best one can], the cinch worked under, and the whole made fast. Sometimes, getting a hit in the pony’s mouth is difficult, and they put on a hackamore, a halter-like rope arrangement, a sort of Rarey hitch, with an extra twist around his jaw instead. Then the second rope is loosed, and the pony is let up, still held by the snubbing-post rope. This is gradually loosened to let the pony have a little fun all to himself, which lie is sure to do, bucking around in a pretty lively fashion for twenty minutes or half an hour to rid himself of the saddle despite the choking of the rope. This takes the feather edge off him, and he will end up playing with foam and quite tired.

Some extra vigorous busters ride the pony right off, but the more judicious prefer to let him tire himself out first. When this is done, the pony is gradually worked out on the prairie and may have to be thrown again to cinch him up and prepare for the ride. To keep him down while the rider gets ready, the other man sits on his head, and the rider puts aside his six-shooter, hat, coat, and everything superfluous but keeps his spurs and quirt. Then he seizes the saddle and gets his foot in the stirrup, the pony is gradually unwound, and the instant he reaches his feet the buster is in the saddle. It is incredible how active these men can be. Then, the real fun begins, and the rider and pony go at it in earnest. The other man sometimes goes along on another horse, with a rope to catch the pony if things work wrong, but he is a wallflower and takes no part in the dancing. It is a pretty rough sport.

The pony may be a running bucker or stand stock-still and buck in place at unexpected intervals; he may buck over a bank; he may buck and pitch a somersault forward; he may rear and fall over backward. The rider wants both to stick to his pony and be ready to vault off in short measure if essential. He uses all the legs nature has given him, stirrup or no stirrup, and lashes his pony with all his might at every rise. The suaviter in modo [gentle in manner] is sunk in the fortiter in re [resolute in execution]. When the pony rises, the trick is to get away from the cantle. The heavy buster has a fashion when the pony comes down of settling himself in his seat with a hard jolt and an “Ugh!” a thing which soon tires out the little fellow, which weighs barely four times as much as the man and is working a dozen times as hard. One way or other, the pony will keep his resistance up for a certain length of time, according to disposition, but in a couple of hours, he will be ridden down. Unless he gets his rider into a snarl and thus earns a let-up, he will be so played out that he will go along pretty quietly, with but slight attacks of his bucking fever. He has found his master, and he knows it. One more ride will be the final polish of his primary schooling. The kindergartening has been omitted. The second ride will repeat the first in a slightly modified and less dangerous form. After this the pony is considered “busted;” but his grammar-schooling he gets from the cowboys use. He never reaches the high or normal school, let alone college, but he has a knack for educating himself, and the amount of information and skill he will pick up of his own accord at cow-punching is terrific. He is taught to guide by the neck, and he twists and turns in performing his duties with extraordinary intelligence and quickness. Still, a good deal of what he does is not so much taught by an educational process as picked up by repetition of the same work, which, after all, is the only way a horse ever learns.

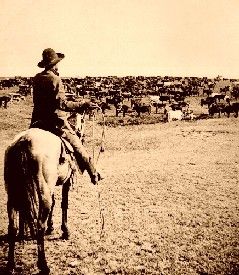

When holding big bunches of cattle, the cowboy will stay in the saddle for an almost unheard-of period, often forty-eight hours at a time. He is up by daylight, works till dark, and then well into the night or all night by turns. He is faithful and untiring and wedded to his master’s interests. Much of the vice attributed to the cowboy must be laid to the score of the evil man of the Plains, a class that used to exist in significant numbers but has been, for the most part, hunted down and driven out by the ranchmen, who were the greatest sufferers. The cowboy is no saint, but he is a manly fellow and averages quite as well as the farmer or mechanic; the stranger who has been cast on his hospitality and has accepted it as tendered would say much higher.

The cowboy rides with the easy balance bred of constant habit, swaying about in the saddle much like a drunken man but with a graceful method in his reeling.

He does not, however, ride all over his horse, like the Indian on his pad or bare-back. When he ropes a steer or a pony, he gets well over on the nigh side, throws his weight against the strain, and rests the back of the right thigh in the saddle.

He can perform all the tricks of the Indian, and much of his fun, as well as his work, is astride his ponies. On foot, he reminds one of Jack ashore, partly from the stiffness of his chaperajos, but with his loose garments, bright kerchief, and jingling spurs, he is a most picturesque fellow, perfectly keeping with his surroundings.

The best cowboys are usually bred to the business, which is not easy to learn. The Southwest yields the best supply. They are apt to claim kinship with the South rather than the East. The word “roundup” originated in the southern Alleghenies, and “corral” was used in Mexico. The cattle business is of Mexican origin, and the dress and method of riding are unquestionably of Spanish descent. But, as in every other business, there are men from every section who succeed and vastly more who fail.

The American cowboy has a Mexican cousin, the vaquero, who does cow-punching in Chihuahua, raises horses for the Mexican cavalry, and an occasional shipment across the Rio Grande. The vaquero is generally a peon and lazy, shiftless, and unreliable vagabond, as all men held to involuntary servitude are wont to be. He is essentially a low-down fellow in his habits and instincts. Anything is grub to him that is not poison, and he will thrive on offal, which no human being except a starving savage will touch.

In his ways, the vaquero is a sort of tinsel imitation of a Mexican gentleman and very cheap tinsel. Our cowboy is independent and quite sufficient unto himself. Everything not cowboy is tenderfoot, cumbering the ground, and of no use in the world’s economy except as a beef consumer. He has as long an array of manly qualities as any fellow living and, despite many rough-and-tumble traits, compels our honest admiration. Also, a small percentage of American cowboys are not decent fellows. One cannot claim so much for the vaquero in question, though the term vaquero covers a great territory and class and applies to the just and unjust alike.

Our Chihuahua vaquero wears white cotton clothes and goat-skin chaperajos with the hair left on, naked feet, huarachos or sandals, and big jingling spurs. A gourd, lashed to his cantle, does the duty of canteen. He rides the Mexican tree, and his saddle is loaded with abundant cheap plunder. His seat is the same as the Mexican gentleman’s — forked, with toes stuck far out to the front and balancing in the saddle.

He is supposed to be a famous and excellent rider. He breaks his own ponies, which sufficiently proves his case. He likes to show off, in the true style of the Romance nations and their offshoots, and will often ride a half-busted bronco with his feet stuck out parade fashion, much as a Yankee boy would carry a chip on his shoulder. But when breaking into his pony, he grips his thigh, knee, calf, and heels, as any rider must.

The Mexican cow ponies are proverbially tough and serviceable. But the vaquero has to turn in most of his good-sized ponies and is apt to be seen on rackabones of undersized or old stock or a mare with a colt at foot. His gait is the lope, with an occasional fox-trot, and he uses his quirt as constantly as an Indian. No savage can be crueler to his pony than a vaquero or pay less heed to his welfare. Averaging the vaquero of northern Mexico, one American cowboy is worth half a dozen of him to work, and though he is used to Apache raids, worth more than a gross of him to fight. This is not a singular fact, given the origin of both these cow-punchers.

The prototype of the vaquero, the Mexican gentleman, is a rider of another quality. No city man ever acquires the second-nature seat on a horse, which one can boast of, as he spends all the working hours of the day and, at times, most of his nights in the saddle. He may be a better horseman; he may be able to ride on the road or do one special thing, such as riding to hounds, or playing polo, or tilting, exceedingly well; but for all that, a chair is more natural to him than a saddle; and to ask him to ride sixteen consecutive hours, which a cowboy does every day, and will double up with a smile, is to ask him to work to the point of complete exhaustion.

Horsemanship is a broader term than mere riding. It, of necessity, comprises the latter to a certain extent. A good horseman must be a good rider, though he may not be perfect, from age or disability. But the best rider may be a very poor horseman. The best wild rider never spares his horse. A good horseman’s first thought is for his beast. But the horseman may be unable to equal the rider’s feats of daring, endurance, skill, or agility. In short, we city folks, compared to the saddle-bred man whose life work is astride a horse, are and remain tenderfoots.

Like most Southern men, the Mexican gentleman is a good rider within his limits. He is the very reverse of the Englishman, who, with his reductio ad simplicitatem [reduced to simplicity] of everything, to the bone. With his tweed suits, his brusque manners, and his disregard for everything that lends a touch of charm to daily life, he has driven out much that is beautiful and more gallant in social and equestrian pleasures.

With lace ruffles and buckled shoes have quite disappeared not only the beauties of equitation, but the graceful outward courtesies to the other sex; and the acknowledgment has not filled the place of the latter conveyed in the cavalier manner now in vogue that women have grown in wisdom to the point of taking care of themselves. Women are glad, no doubt, of some emancipation, but does she, whom we love and admire as an honest woman of today, want to be left to her own resources any more than her grandmother? Has she tired of the willing ministrations of the other sex? We have by no means lost our heart courtesies, but whither has the old-fashioned polish taken its flight? We are indebted for much to the Old Country; do not let us borrow too largely. Despite our antebellum accusation that the South affiliated with the British aristocracy, the Southern has retained his gallantry to women, as we of the Eastern States, to our serious detriment, have not. The best rule in equitation, as in other arts, is first the useful, then the ornamental. But having the useful, by no means let the ornamental elude you, unless the twain be compatible.

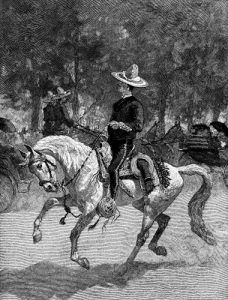

Our artist has drawn the typical rider on the Paseo de la Reforma, the Rotten Row, or Harlem Lane of the city of Mexico. In this style ride both the statesman and the swell, the banker and (when he can afford it) his clerk. And very much so rode the Englishman of half a century ago. I have heard excellent English horsemen brush aside all reference to the high school of equitation as worthy only of a snob. But there were some very decent “snobs” in England back in the thirties, when celebrated members of both Houses, the leaders of fashion, the most noted generals – the very men, indeed, who had beaten Boney – and everyone pretending to be in the social swim would go prancing up and down the Row, passaging, piaffing, traversing, to the admiration of all beholders. Even the M.F.H. fell into the trick of it in the Park. They were not called snobs then; the initial letter was dropped, and when a Briton slurs at the better education of the horse today, he casts a stone at his own ancestry over the shoulder of the high school lover.

The first thing in our Mexican friend that strikes us is his horse. This is not the bronco of the Plains. He is imported from Spain, or lately bred from Spanish stock, without that long struggle for existence which has given the pony his wonderful endurance and robbed him of every mark of external beauty. Here, we revert to the original Moorish type. The high and long-maned crest, arched with pride, the full red nostril, large and docile eye, rounded barrel, high croup, tail set on and carried to match the head, clean legs, high action, and perfect poise. How he fills our artistic eye! How we dwell upon him! Until we remember that performance comes first, beauty after and that the English thoroughbred, which can give a distance to the best of this exquisite creature family and beat him handily, has developed from the same blood for other lines than these, or, indeed, that the meanest runt of a Plains pony, on a ride of a hundred miles across the Bad Lands, would leave the beautiful animal dead in his tracks full two score miles behind!

The Mexican swell rides on a saddle worth a fortune. It is loaded with silver trimmings, and hanging over it is an expensive serape, or Spanish blanket, which adds to the magnificence of the whole. His queer-shaped stirrups are redolent of the old mines. His bridle is, in like manner, adorned with metal in the shape of half a dozen big silver plates, and to his bit is attached a pair of knotted red cord reins, which he holds high up and loose.

He is dressed in a black velvet jacket fringed and embroidered with silver, and a huge and expensive hat, perched on his head, is tilted over one ear. His legs are encased in dark, tight-fitting breeches, with silver trimming down the side seams, but cut so as, in summer weather, to unbutton from the knee down and flap aside. His spurs are silver, big, heavy, costly, and fitted to buckle around his high-cut heel. Under his left leg is fastened a broad-bladed and beautiful curved sword, with a hilt worthy a prince of the blood.

The seat of this exquisite is the perfect pattern of a clothespin. Leaning against the cantle, he stretches his legs forward and outward, with heels depressed in a fashion that reminds one of Sydney Smith’s saying that he did not object to a clergyman riding if only he rode very severely and turned out his toes. It is the very converse of riding close to your horse. In what it originates, it is hard to guess unless bravado. With an equally short seat and long stirrups, the cowboy keeps his legs where they belong, and if his leg is out of the perpendicular, it will be so to the rear.

The rack rarely, the canter all but universally, is ridden by the Mexican. Only the Englishman and those he has taught ride what can be called a trot. The trot is a mere jog with all others, though a good open trot is one of the easiest gaits for a horse. Luckily, as the horses of the world gain in breeding by using English stock, the world is learning the English habit of rising. As a schoolboy in Prussia, I was fairly hooted out of rising to a trot. But now you see the Prussian and all other Continental officers riding a la’ Anglaise [in the English manner] in full uniform. One may see a lancer or hussar trotting through the streets with a handful of dispatches, leaning over his horse’s neck and rising to the gait in a fashion that would have court-martialed him in the old ramrod Anglophobia days of Frederick William IV. For all they laugh at England for her military pretensions, they adopt many good things from her, not the least of which is the course of cross-country riding all foreign officers are now required to take.

The canter of the Mexican is the old park canter, with a superabundant use of the curb to make the horse prance and play and show his action. But we must not look down upon him. He is doing nothing more than the men who used to go titupping down Rotten Row every fine afternoon 50 years ago, and he may be a better rider than he looks.

This trot and canter controversy is not yet settled. The Englishman claims his horse can go seven miles on a trot for six on a canter. Our cavalry officers on the Plains arrived at a similar conclusion, and all long marches were made at alternate walk and trot or walk alone. Most cavalry does this. But you cannot make a Southerner or a Plainsman adopt this theory. The Southern horse goes his so-called artificial gaits or canters: you cannot give away a trotter for the saddle. The bronco canters all but exclusively. The matter seems to depend on inbred habit, and comparative statistics on the subject, however interesting, could scarcely be made accurate.

By Colonel Theodore Ayrault Dodge 1891. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025. About the Author: Colonel Theodore Ayrault Dodge was a Union officer and a military historian during the Civil War. His primary writings were on the war and military history, but he also wrote this article, Some American Riders, which appeared in Harper’s Magazine in July 1891.

Also See:

Cowboys on the American Frontier

List of Trail Blazers, Riders, & Cowboys

The Range of the American West

Tales & Trails of the American West