By Edgar Beecher Bronson in 1910

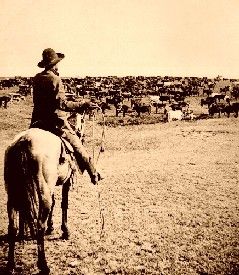

Shanghai Rhett’s death at Llano, Texas, made another hole in the rapidly thinning ranks of the pioneer Texas cow hunters. Cow hunting in its early days was the industry upon which many of the state’s greatest fortunes were founded. From it sprang the great cattle ranch industry, which, between 1866 and 1885, converted into gold the rich wild grasses of the tenantless plains and mountains of Texas, New Mexico, Indian Territory, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Dakota, and Montana.

The economic value of this great industrial movement in promoting the settlement and development of that vast region of the West lying between the 98th and 120th meridians and embracing half the total area of the United States is comprehended by few who were not personally familiar with the conditions of its rise and progress. There can be no question that the ranching industry hastened the occupation and settlement of the Plains by at least 30 years.

Farming in those wilds was then an impossibility. Remote from rail ays, unmapped, and un-trod by white men, it was under the sway of hostile Indians, before whose attacks isolated farming settlements, with houses widely scattered, would have been defenseless. Moreover, there was neither a market nor a means of transportation for the farmer’s product. The Texas cow hunters changed all these conditions, and they did it in over a decade.

In Texas, the leaders and rank and file of that great army of cow hunters were bred, destined to become the pioneers of this vast region. Pistols and knives were the treasured toys of their childhood. They were inured to danger and hardship. They were expert horsemen, trained Indian fighters, reckless of life but cool in its defense. Thus, they were an ideal class for the pacification of the Plains.

Shanghai Rhett’s death removed one of the comparatively few survivors of this most interesting and eventful past.

In Texas after the Civil War, when Shang was young, a pony, a lariat, a six-shooter, and a branding iron were sufficient for acquiring wealth. A trained eye and a practiced hand were necessary to use a pistol and lariat effectively; the running iron anybody could wield; therefore, while a necessary feature of equipment, the iron was a secondary affair. The pistol helped settle annoying title questions; the horse and the lariat took possession after the title was settled; the iron marked the property with a symbol of ownership. The property in question was always cattle.

Before the Civil War, cattle were abundant in Texas, with few fences. Therefore, the cattle roamed at will over hills and plains. To determine ownership, each owner adopted a distinctive “mark and brand.” The owner’s mark and brand were put upon the young before they left their mothers and grown cattle when purchases were made. Thus, the broads des and quarters of those who had changed hands were often covered with this barbarous record of their various transfers.

The system of marking and branding originated among the Mexicans. Marking consists of cutting the ears or some part of the animal’s hide in such a way as to leave a permanent distinguishing mark. One owner would adopt the “swallow fork,” a V-shaped piece cut out of the tip of the ear; another, the “crop,” the tip of the ear cut squarely off; another, the “under-half crop,” the under half of the tip of the ear cut away; another, the “over-half crop,” the reverse of the last; another, the “under-bit,” a round nick cut in the lower edge of the ear; another, the “over-bit,” the reverse of the last; another, the ” under-slope,” the under half of the ear removed by cutting diagonally upward; another, the “over-slope,” the reverse of the last; another, the “grub,” the ear cut off close to the head; another, the “wattle,” a strip of the hide an inch wide and two or three inches long, either on the forehead, shoulder, or quarters, skinned and left hanging by one end, where before healing it leaves a conspicuous lump; another, the “dewlap,” three or four inches of the loose skin under the throat skinned down and left hanging.

Branding consists of applying a red-hot iron to any part of the animal for six or eight seconds until the hide is seared. Adequately done, hair never again grows on the seared surface, and the animal is “branded for life.” A small five-inch brand on a young calf becomes a significant 12-to-18-inch mark when the beast is fully grown. In Mexico, the art of branding dates back to when few men were lettered, and most men used a flourish instead of a written signature. Thus, in Mexico, the brand was always a device, whatever complex combination of lines and circles the owner’s whim may conceive. In this country, the brand was usually a combination of letters or numerals, though shapes and forms are sometimes represented. Branding and marking cattle and horses is a cruel practice, but under the old open range conditions, where individual ownerships numbered thousands of heads, no other means existed of distinguishing title.

During the Civil War, these vast herds grew and increased unattended, neglected by owners in the field with the armies of the Confederacy. So it happened that hundreds of thousands of cattle ranged the plains of Texas after the war, unmarked and unbranded, wild as the native game, to which no man could establish title. This situation afforded an opportunity that the hard-riding and desperate men who found themselves stranded on this far frontier after the wreck of the Confederacy were quick to seize. Shang Rhett was one of them. From chasing Fed ral soldiers, they turned to chasing unbranded steers and found the latter occupation no less exciting and much more profitable than the former.

First, bands of free companions rode together and pooled their gains. Then, the thrift of some and the improvidence of others set the immutable distribution laws in motion. Soon, a class of rich and powerful individual owners was created, who employed great outfits of 10 to 50 men each, splendidly mounted and armed. These outfits continually moved camps and traveled light, without wagons or tents.

With the mild climate, even in winter, seldom more than two blankets were carried to the man for bedding. The cooking paraphernalia was simple: a coffee pot, a frying pan, a stew kettle, and a Dutch oven. Each man carried a tin cup tied to his saddle. Plates, knives, and forks were considered unnecessary luxuries, as every man wore a bowie knife at his belt and was dexterous in using his slice of bread as a plate to hold whatever delicacy the frying pan or kettle might contain. Sometimes, even the Dutch oven was dispensed with bread, and it was baked by winding thin rolls of dough around a stick and planting the stick in the ground, inclined over a bed of live coals. The frying pan was often left behind, the meat roasted on a stick over the fire, and no meat in the world was ever so delicious as a good fat side of ribs so roasted.

The wild, unbranded cattle were everywhere — in the cross-timbers of the Palo Pinto, in the hills and among the post oaks of the Concho and the Llano, on the broad savannas of the Lower Guadalupe and the Brazos Rivers, in the plains and mesquite thickets of the Nueces and the Frio. And through these wild regions, on the outer fringe of settlement, ranged the cow-hunters, as merry and happy a lot as ever courted adventure, careless of their lives.

Of adventure and hazard, the cow-hunters had enough to keep the blood tingling. They had to deal with wild men as well as wild cattle. Comanche and Kiowa, the old lords of the manor, were bitterly disputing every forward movement of the settler along the whole frontier. No community, from Fort Griffin to San Antonio, escaped their attacks and depredations.

Indeed, these incursions were regular monthly visitations, always made “in the light of the moon.” A war party of naked bucks on naked horses, the lightest and most dexterous cavalry in the world, would slip softly near some isolated ranch or lonely camp by night. The most clever and cunning would dismount and steal swiftly in upon their quarry. Slender, sinewy, bronze figures creeping and crouching like panthers, crafty as foxes, fierce and merciless as maddened bulls, their presence was rarely known until the blow fell. Sometimes, they were content to steal the settlers’ horses and be many miles away to the West or north by daylight. Sometimes, they fired buildings and shot down the inmates as they ran out. Sometimes, they crept silently into camps, knifed or tomahawked one or more of the sleepers, and stole away, all so noiselessly that others sleeping near were undisturbed. Sometimes, they lay in ambush about a camp till dawn and then, with mad war-whoops, charged among the sleepers with their deadly arrows and tomahawks.

Against these wily marauders, the cow-hunters could never abate their guard. And it was these same cow hunters the Indians most dreaded, for they were tireless on the trail and utterly reckless in an attack. It was not often the Indians got the best of them, and only by ambush or overwhelming numbers. Better armed, of stouter hearts in a stand-up fight, little bands of these cow-hunters often soundly thrashed war parties outnumbering them ten to one.

Then, it not infrequently fell out that collisions occurred between rival outfits of cow hunters and disputes over territory or cattle, which led to bitter feuds not settled till one side or the other was killed off or run out of the country. Battles royal were fought more than once, and a score or more of men were killed, whereas the casus belli was a difference in the ownership of a brindle steer.

These men were a law unto themselves. Courts were few and far between on the line of the outer settlements. Powder and lead came cheaper than attorneys’ fees and were, moreover, found to be more effective. Thus, the rifle and pistol were almost invariably the cow hunters’ court of first and last resort for disputes of every nature. Except in rare instances where there happened to be survivors among the families of the original plaintiff and defendant, this form of litigation was never prolonged or tiresome. When there were any survivors, the case was sure to be reargued.

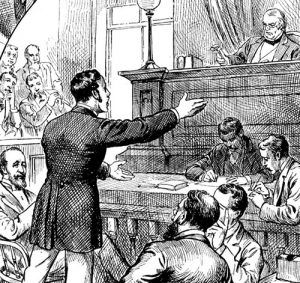

Occasionally, a case would be brought to formal trial before a judge and jury in the immediate settlements. While, as a rule, the procedure of these courts conformed to the statutes and was formal enough, rather startling informalities sometimes characterized their sessions. A case in point occurred at Llano, of which Shang Rhett was the hero. Chance for his life, or else he probably would not have been brought to trial at all. And even despite the general disapproval, there was an undercurrent of sympathy for him in the community.

At that time, Llano could boast of only one building, a big rough stone house, loop-holed for defense against the Indians. Under this one roof, the enterprising owner assembled a variety of industries and performed various functions that would dismay the most versatile man of any older community. Here, he kept a general store, operated blacksmith and wheelwright shops, served as post-master, ran a hotel, and sat as a justice of the peace. Indeed, he got as much in the habit of self-reliance in all emergencies that, in more than one instance, he subjected himself to criticism by calmly sitting as both judge and jury in cases wherein he had no jurisdiction. Getting a jury a Llano was no easy task. The country for miles might often be scoured without producing a full panel.

Llano, being the county seat and the only house in town, somewhat naturally, from time to time, enjoyed temporary distinction as a courthouse when, at long intervals, the Llano County court met. The accommodations, however, were inconveniently limited — so limited that on one occasion, at least, they were responsible for a sad miscarriage of justice.

A murder trial was on. One of the earliest settlers, a man well-known and generally liked, had killed a newcomer. It was felt that he had given his victim no chance for his life, else he probably would not have been brought to trial at all. And even despite the general disapproval, there was an undercurrent of sympathy for him in the community.

However, the court met, and the case was called. Several settlers were witnesses in the case. It was, therefore, considered remarkable and encouraging evidence of Llano County’s population growth when the District Attorney succeeded in raking together enough men for a jury. At noon on the second day of the trial, the evidence was all in, the arguments of counsel finished, and the case was given to the jury. The prisoner’s case seemed hopeless. A premeditated murder had been proved, against which scarcely any defense was produced.

Judge, jury, prisoner, and witnesses all had dinner together in the “courtroom,” which was constantly demeaned from its temporary dignity as a hall of justice to the humble rank of a dining room as soon as the court adjourned. Directly after dinner, the jury withdrew for deliberation in the custody of two bailiffs.

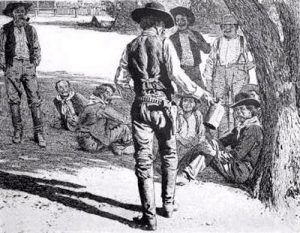

To be sure, the house was large, but its capacity was already so far taxed that it could not provide a jury room. Therefore, it was the custom of the bailiffs to use an open, mossy clearing shaded by an incredible live oak tree on the farther bank of the Llano and distant two or 300 yards from the courthouse as a jury room. Therefore, the jury and the bailiffs retired to some distance, and discussion of a verdict was begun. Despite the weight of evidence against him, two or three were for acquittal. The others said they were “damned sorry; Jim was a mighty good feller, but it appeared like they’d have to foller the evidence.” So the discussion, pros, and cons ran on into the mid-afternoon without result.

It was an intensely hot afternoon; the air was close and heavy with humidity, and it was an hour when all Texans who could do so took a siesta. Judge and counsel were sleeping peacefully on the gallery of the distant courthouse, and the two bailiffs guarding the “jury room,” overcome by habit and the heat, were stretched at full length on the ground, snoring in concert. This situation made the opportunity for a friend at court. Shang Rhett was the friend awaiting this opportunity. A few paces brought him among the jurors, stepping lightly out of the brush where he had been concealed.

“Howdy! boys? ” Shang dr wled. Pow’ful hot evenin’, ain’t it? Moseyin’ roun’ s rt o’ lonesome like, I thought mebbe so you fellers ‘d be tired o’ talkin’ law, an’ I’d jes’ step over an’ pass the time o’ day an’ give you a rest.”

Shanghai Rhett approaches the jury

A rude diplomat, perhaps, Shang was nevertheless a cunning one. Several jurors e pressed their appreciation of his sympathy, and one answered: “Tired o’ talkin’! Wall, I reckons. I’m jes’ tireder an’ dryer ‘n if I’d been tailin’ down beef steers all day. My ol’ tongue’s een a-floppin’ till thar ain’t nary ‘nother flop left in her ‘nless I could git to ile her up with a swaller o’ red-eye, an’ — ” regretfully — “I reckon thar ain’t no sort o’ chanst o’ that.”

“Thar ain’t, hey?” replied Shang, producing a big jug from the brush nearby. “‘Pears like, ‘n ess I disremember, thar’s some red-eye in this yere jug.”

Upon examination, the jug was found to be nearly full, but passed and repassed around the “jury room,” it was not long before the jug was empty and the jury full.

Shrewdly seizing the right moment before the jurors got drunk enough to be obstinate and combative, Shang made his appeal. “Fellers,” he said, ” I allows you all knows that Jim’s my friend, an’ I reckon you cain’t say but what he’s been a mighty good friend to more’n one o’ you. Course, I know h got terrible out o’ luck when he had t’ kill this yer Arkinsaw feller. But then, boys, rkinsawyers don’t count fer much nohow, do they? Powful onery, no account lot, sca’cely fit to practise shootin’ at. We fellers ain’t a-goin’ to lay that up agin Jim, air we? We ain’t a-goin’ to help this yer jack-leg prosecutin’ attorney send ol’ Jim up. Why, fellers, we knows well enough that airy one o’ us might ‘a done the same thing ef we’d been out o’ luck, like Jim was, in meetin’ up with this yer Arkinsawyer afore we’d had our mornin’ coffee. What say, boys? ein’ as how any o’ us might be in Jim’s boots mos’ any day, reckon we’ll have to turn him loose? ”

Shang’s pathetic appeal for Jim’s life clearly won more than half the jury, but there were several who, while their sympathies were with Jim, ” ‘lowed they’d have to bring a verdic’ accordin’ to the evidence.”

“Verdic’? Why, fellers,” retorted Jim’s advocate, “whar’s the use of a fool verdic’? ‘Sposin’ we fell rs was goin’ to be verdicked? This is a time for us fellers to stan’ together, shua’. I’ll tell you wh t le’s do; le’s all slip off inter th’ brush, cotch our hosses an’ pull our freight fer home. This year court ain’t goin’ to git airy jury but us in Llano ’till a new ones grown, and if we skip, I reckon they’ll have to turn Jim loose.”

This alternative met all objections. In a moment, the “jury room” was empty.

Shortly thereafter, the two bailiffs, awakened by a clatter of hoofs over the rocky hills behind them, were doubly shocked to find the only tenant of the “jury room ” an empty jug.

One of the bailiffs sighted some of the escaping jurors and opened fire; the other hastened to alarm the court. The latter, running toward the house, met the judge and counsel roused by the firing and yelled out: “Jedge, the hull jury’s stampeded! Bill’s winged two o’ them. Gi’ me a fast ho s an’ a lariat an’ mebbe so I’ll cotch some more.”

Two or three jurors who were too much fuddled with drink to saddle and mount were quickly captured. The rest escaped. Of course, the court was outraged and indignant, but it was powerless. So Jim was released, thanks to Shang’s diplomacy and eloquence. And, by the way, in the dark days that came to ranchmen in 1885, Jim, risen to be a well-known and powerful banker in City, furnished the ready money necessary to save Shang’s imperiled fortune, and when at length, he heard that Shang was at death’s door, Jim found the time to leave his large affairs and come all the way up from to Llano to bid his old friend farewell.

The cow hunters accumulated cattle for two or three years after the Civil War. From Palo Pinto to San Diego, great outfits worked incessantly, scouring the wilds for unbranded cattle.

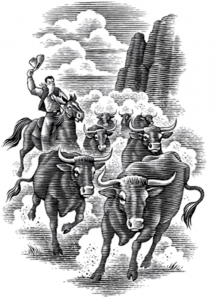

When an animal was sighted, one or two mad riders would spur in pursuit, rope him by horns or legs, and throw him to the ground. Then, dismounting and springing nimbly upon the prostrate beast, they quickly fastened the beast’s feet with a “hogtie” hitch so that he could not rise, a fire was built, the short saddle iron heated, and the beast branded. The feet were then unbound, and the cow-hunter flew into his saddle and spurred away to escape the infuriated charge sure to be delivered by his maddened victim.

In this, workhorses were often fatally gored, and not a few men lost their lives. Even though it was such a downright desperate task, the men became so expert that they did not hesitate to tackle, alone and single-handed, great bulls of twice the weight of their small ponies; they roped, held, threw, and branded them. The least accident t or mistake, a slip of the foot, a stumble by one’s horse, a breaking cinch, a failure to maintain full tension on the lariat, slowness in dismounting to tie an animal or in mounting after it was untied — any one of these things happening meant death unless the cow-hunter could save himself with a quick and accurate shot. Indeed, the boys loved this work and were so proud of their skill that when an unusually vicious old ” moss-back ” was encountered, each strove to be the first to catch and master him. And God knows th y should have loved it, as must any man with real red blood coursing through his veins, for it did not work; I libel it to call it to work; it was instead a sport and the most glorious sport in the world. Riding to hounds over the stiffest country or hunting grizzly in juniper thickets is tame beside cow-hunting in the old days.

The happiest period of my life was my first five years on the range in the early seventies. Indeed, it was a period so happy that memory played me a shabby trick to recall its incidents and fire me with longings for pleasures I may never again experience. Its scenes are before me now, vivid as if they were yesterday.

The night camp is made beside a singing stream or a bubbling spring; the night horses are caught and staked; there is a roaring, merry fire of fragrant cedar boughs; a side of fat ribs is roasting on a spit before the fire, its sweet juices hissing as they drop into the flames, and sending off odors to drive one ravenous; the rich amber contents of the coffee pot is so full of life and strength that it is well-nigh bursting the lid with joy over the vitality and stimulus it is to bring you. Supper was eaten there follow pipe and cigarette, jest and badinage over the day’s events; stories and songs of love, of home, of the mother; and rude impromptu epics relating the story of victories over vicious horses, wild beasts, or savage Indians. When the fire had burnt low and become a mass of glowing coals, voices were hushed, the camp was still, and each, half hypnotized by gazing into the weirdly shifting lights of the dying embers, was wrapped in introspection. Then, rousing, y u lie down, your canopy, the dark blue vault of the heavens, your mattress, the soft, curling buffalo grass.

After a deep, refreshing sleep, you spring at dawn with every faculty renewed and tense. Breakfast eaten, you catch a favorite roping horse, square and heavy of shoulder and quarter, short of the back, with wide nervous nostrils, flashing eyes, ears pointing to the slightest sound, pasterns supple and strong as steel, and of a nerve and tempeconstantlyys reminding you that you are his master only by sufferance. Now begins the d y’s hunt. Riding softly th ough cedar brake or mesquite thicket, slipping quickly from one live oak to another, you come upon your quarry, some great tawny yellow monster with sharp-pointed, wide-spreading horns, standing startled and rigid, gazing at you with eyes wide with curiosity, uncertain whether to attack or fly.

Usually, he at first turns and runs, and you dash after him through timber or over plain, the great loop of your lariat circling and hissing about your head, the noble horse between your knees straining every muscle in pursuit, until, come to fit distance, the loop is cast. It settles and tightens around the monster’s horns, and your horse stops and braces itself to the shock that may throw the quarry or cast the horse and rider to the ground, helpless at his mercy. Once he is caught, woe to you, if you cannot master and tie him, for a struggle, is on, a struggle of dexterity and intelligence against brute strength and fierce temper that cannot end till beast or man is vanquished!

Thus were the great herds accumulated in Texas after the Civil War. But cattle were so abundant that their local value was trifling. Markets had to be sought. The only outlets were the mining camps and Indian agencies of the Northwest and the railway construction camps pushing west from the Missouri River. So the Texans gathered their cattle into herds of 2000 to 3000 head each and struck north across the trackless Plains. Indeed, this movement reached such proportions that, excepting in a few narrow mining belts, there is scarcely one of the more significant cities and towns between the 98th and 120th meridians that did not have its origin as a supply point for these nomads. Between 1866 and 1885, 5,713,976 head of cattle were driven northward from Texas.

Afterward, the range business on a large and profitable scale was practically done and ended. In Texas, very few open ranges could turn off fair grass beef. With the good lands farmed and the poor lands exhausted, the ranges become narrower every year, and every year, the cost of getting fat grass steers was eating deeper into the range man’s pocket. Of course, there were still isolated ranges where the range men still hung on, but they are not many, and most of them would later fall prey to the plow.

When the range man was forced to lease land or buy waterfronts in the Territories and build fences, his fate was soon sealed. With these conditions, he soon found that the sooner he reduced his numbers, improved his breed, and went on tame feed, the better. A corn shock is a more profitable close herder than any cow-puncher who wore spurs. This is a sad thing for a range man to contemplate, but it is nevertheless the simple truth. Soon, the merry crack of the six-shooter will no more be heard in the land, its wild and woolly manipulator being driven across the last divide, with a faint show of resistance, by an unassuming granger and his all-conquering hoe.

Like many others in the past, the range man has served his purpose and survived his usefulness. His work is practically done, and few realize what a noble work it has been or its cost in hardship and danger.

I refer, of course, not alone to the development of a great industry, which in its time has added millions to the country’s material wealth, but to its collateral results and influence. But for the vent resume range man and his rifle, millions of acres from the Gulf in the South to Bow River in the far Canadian Northwest, now constituting the peaceful, prosperous homes of hundreds of thousands of thrifty farmers, would have remained for many years longer what it had been from the beginning — a hunting and battleground for Indians, and a safe retreat for wild game.

What was the hardship and what the personal risk with which this great pioneer work was accomplished, few know except those who had a hand in it, and they, as a rule, were modest men who thought little of what they did, and now that it is done, say less.

By Edgar B. Bronson, 1910. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

About the Author: Edgar Beecher Bronson wrote The Red-Blooded Heroes of the Frontier. This article is a chapter of this book, published by A.C. Mcclurg & Co. in 1910. Bronson worked not only as a reporter and writer, publishing several books and articles, but also as a cowboy and a rancher. As it appears he e, the text is not verbatim, however, as it has been edited for clarity and ease of the modern reader.

Also See:

Cowboys, Trail Blazers & Stage Drivers