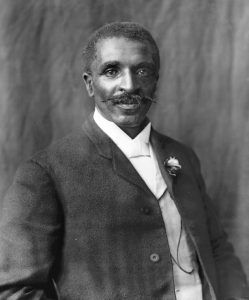

George Washington Carver, 1906. Photo by Benjamin F. Johnston.

Time Magazine once called George Washington Carver a “Black Leonardo,” a title worthy of this great scientist, educator, botanist, and inventor.

Carver was born in Diamond Grove, Missouri, in January 1864, although the exact date is unknown, and some evidence points to 1861. His slave parents, Mary and Giles, were owned at the time by German American immigrant Moses Carver.

Not long after his birth, George, along with his Mother, was kidnapped by Confederates from Arkansas and sold in Kentucky. Turmoil would soon prevail. Moses Carver moved into action, hiring a man named John Bentley to find them. Fortunately for George, Bentley tracked him down, and Moses negotiated his return to Missouri, with the ransom being a racehorse valued at $300. Unfortunately, George’s mother, Mary, wasn’t found.

Not long after his return to Missouri, slavery ended for his family. George was a sickly child, now orphaned, and Moses Carver and his wife, Susan, took him and his brother under their wings. Due to his frailty, Carver wasn’t required to do the more laborious chores around the farm and spent a lot of time exploring nature and tending the Carvers’ gardens around the house. Flowers around the property flourished, and when a visitor asked George how to make her own prettier, he told her to “love them.”

George’s talent got him noticed around the small community of Diamond Grove, and people began calling him the Plant Doctor. He even made house calls, prescribing remedies for sick plants or taking them into the woods, where he had a secret garden, to nurse them back to health.

During this time, Susan Carver taught George how to read since black children were not allowed in the local schools. George had a thirst for knowledge, so when he saw several black children going into a school during a trip to Neosho, ten miles south, he immediately knew he had to attend. Only 11 at the time, he told the Carvers that he would move to Neosho to go to school, saying he would figure out how to provide for himself using some of the knowledge he had gained through Susan. The Carvers decided not to stop him, and George made his way there.

His first night was spent in the loft of a barn near the schoolhouse. The next morning, as George awaited the school to open, he met Mariah Watkins, reportedly the owner of the home and barn where he had stayed. He stated that he wanted to rent a room and identified himself as “Carver’s George” as he explained his intentions to attend the school as a student. Carver later recalled that Watkins replied that from now on, his name was “George Carver.” She also made an impression on young George when she said: “You must learn all you can, then go back into the world and give your learning back to the people.”

Carver’s road through education wound through several schools. At age 13, he wanted to attend an academy in Fort Scott, Kansas, but didn’t stay long after witnessing a group of whites kill a black man. After attending several other schools, Carver finally earned his diploma from Minneapolis, Kansas High School.

Applying to several colleges, he was accepted at Highland College in Highland, Kansas, in 1886. His hopes of higher education were immediately dashed upon arrival as the college rejected him due to his race. From there, he wound up in Ness County, Kansas, where he homesteaded a claim. There, he maintained a small conservatory of plants and flowers along with a geological collection. He also maintained 17 acres of crops ranging from rice and corn to fruit trees while earning money as a ranch hand and doing odd jobs in nearby Beeler.

He managed to get an education loan from the Bank of Ness City and left there in 1890 to study art and piano at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa. His art teacher, recognizing Carver’s talent for painting plants and flowers, encouraged him to study botany. That same year, he became the first black student at Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames.

After completing his Bachelor’s Degree, a couple of his professors talked him into continuing his education at Iowa State for his Master’s. During this time, he did research at the Iowa Experimental Station, which gained him his first national recognition and respect as a botanist.

George Washington Carver in the Field, 1902. Photo by Benjamin F. Johnston.

After earning a Master’s Degree, Booker T. Washington of the African-American Tuskegee Institute, in Tuskegee, Alabama, offered Carver a job as head of its Agriculture Department. It would be here that Carver would do most of his incredible work as not only an educator but also a scientist. He even designed a mobile classroom he called a “Jesup wagon”, named after philanthropist Morris Jesup, who provided some of the funding for the program. He used it to educate the farmers, teach crop rotation methods, and introduce alternative cash crops while improving the soil depleted from repeated cotton planting.

In 1915, George Carver began concentrating on research into new uses for peanuts, sweet potatoes, soybeans, pecans, and other crops. He would become one of the most well-known African Americans of his time due to his testimony before Congress in 1921 in support of tariffs on imported peanuts and his speaking at the national conference of the Peanut Growers Association that previous year.

Carver had tremendously helped the farmers of the South learn to improve their depleted soils through crop rotation, restoring nitrogen to the soil. This practice, taught by Carver and several other agriculture experts, improved cotton yields and gave farmers alternative crops of sweet potatoes, soybeans, and the like. His works had even been publicly admired by President Theodore Roosevelt early on, who knew of Carver through former professors in Iowa who had gone on to serve in his cabinet.

During his 47 years at the Tuskegee Institute, he reputedly discovered 300 uses for peanuts and hundreds more for soybeans, pecans, and sweet potatoes. However, he only obtained three patents, none of which were commercially successful. In addition, Carver left no records of making his products and did not keep a laboratory notebook. Although credited in the past for inventing peanut butter, that is not true, as other cultures have made it for centuries. In addition, Marcellus Gilmore Edson was awarded a patent for the manufacture of peanut butter in 1884 when Carver was only 20.

During the last couple of decades of his life, Carver was well-known and traveled to promote Tuskegee, peanuts, and racial harmony despite his limited commercial successes. He met with three U.S. Presidents (Teddy Roosevelt, Coolidge, and Franklin Roosevelt), and even the Crown Prince of Sweden studied with him for several weeks. And although some say his claims to fame were exaggerated, he still left an incredible legacy in agriculture. He died on January 5, 1943, having never married. Buried beside Booker T. Washington in Tuskegee, his grave says, “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”

In July of that same year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated funds for the George Washington Carver National Monument near Diamond, Missouri. This was the first national monument dedicated to an African American and the first to honor someone other than a President. In 1977, Carver was elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, and in 1990, into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. These are but a few of his honors, as there are dozens of schools named after him, and many institutions continue to honor him today.

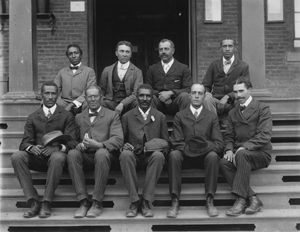

George Washington Carver with staff.

For more information:

George Washington Carver National Monument

5646 Carver Road

Diamond, MO 64840-8314

Phone Headquarters 417-325-4151

Fax 417-325-4231

©Dave Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2025.

Also See:

African Americans – From Slavery to Equality

“When our thoughts, which bring actions, are filled with hate against anyone, Negro or white, we are all in a living hell. That is as real as hell will ever be.”

– George Washington Carver

Sources:

National Library Of Congress

Inventors Hall of Fame

George Washington Carver National Monument