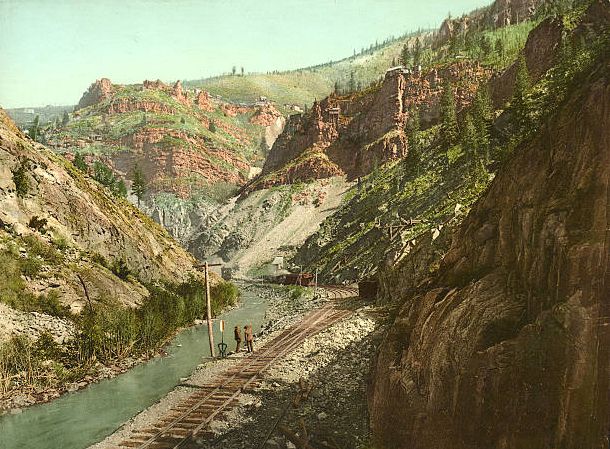

Gold Mining in California by Currier & Ives.

By Charles Austin Beard and Mary Ritter Beard, 1921

Mineral Resources – In the Far West, mining predominated over agriculture. Indeed, the minerals rather than the land attracted the pioneers who opened the country. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 marked the beginning of the great rush of prospectors, miners, and promoters who explored the valleys, climbed the hills, washed the sands, and dug up the soil in their feverish search for gold, silver, copper, coal, and other minerals. In Nevada and Montana, mineral resource development occurred during the Civil War. Alder Gulch became Virginia City in 1863; Last Chance Gulch was named Helena in 1864; and Confederate Gulch was christened Diamond City in 1865. At Butte, mining operations began in 1864, and within five years, the miners had extracted eight million dollars’ worth of gold. Under the gold, they found silver; under the silver, they found copper.

Even at the end of the 19th century, after agriculture had advanced significantly and stock and sheep raising were introduced on a large scale, minerals continued to be the chief source of wealth in several states. This was revealed by the figures for 1910. Colorado’s gold, silver, iron, and copper were worth more than the wheat, corn, and oats combined; the copper of Montana sold for more than all the cereals and four times the price of the wheat. Nevada’s interest was also primarily in mining, with receipts from the mineral output exceeding $43,000,000, or more than half of the national debt of Hamilton’s day. The yield of the mines of Utah was worth four or five times the wheat crop; the coal of Wyoming brought twice as much as the great wool clip; the minerals of Arizona were totaled at $43,000,000 as against a wool clip reckoned at $ 1,200,000; while in Idaho alone of this group of states did the wheat crop exceed in value the output of the mines.

Timber Resources – Unlike those of the Ohio Valley, the forests of the Great West proved a boon to the pioneers rather than a foe to be attacked. In Ohio and Indiana, for example, the frontier line of homemakers had to cut, roll, and burn thousands of trees before they could put out a crop of any size. Beyond the Mississippi River, however, there were already for the breaking plow great reaches of almost treeless prairie, where every stick of timber was precious. In the other parts, often rough and mountainous, where ancient forests of the finest woods stood, the railroads made good use of the timber. They consumed acres of forests to make ties, bridge timbers, and telegraph poles, and laid a heavy tribute upon the forests for their annual upkeep. The surplus trees, such as had burdened the pioneers of the Northwest Territory a hundred years before, they carried off to markets on the east and west coasts.

Western Industries – The peculiar conditions of the Far West stimulated a rise of industries more rapidly than is usual in the new country. Mining activities, which in many sections preceded agriculture, called for sawmills to furnish timber for the mines and smelters to reduce and refine ores. The ranches supplied sheep and cattle for the packing houses of Kansas City and Chicago, Illinois. The waters of the Northwest afforded salmon for 4000 cases in 1866 and 1,400,000 cases in 1916.

The fruits and vegetables of California gave rise to numerous canneries. The lumber industry, which began with crude sawmills to supply rough timbers for railways and mines, evolved into specialized factories for producing paper, boxes, and furniture. As the railways preceded settlement and furnished a ready outlet for local manufactures, they encouraged the early establishment of varied industries, thus creating a state of affairs quite unlike that obtained in the Ohio Valley in the early days before the opening of the Erie Canal.

Social Effects of Economic Activities – In many respects, the social life of the Far West also differed from that of the Ohio Valley. Though open to homesteads, the treeless prairies favored the great estate tilled partly by tenant labor and partly by migratory seasonal labor, summoned from all over the country for the harvests. The mineral resources created hundreds of huge fortunes, which made the accumulations of eastern mercantile families look trivial by comparison. Other millionaires won their fortunes in the railway business and still more from the cattle and sheep ranges. In many sections, the “cattle king,” as he was called, was as dominant as the planter in the old South. Throughout the grazing country, he was a conspicuous and important figure. He “sometimes invested money in banks, railroad stocks, or city property… He had his rating in the commercial reviews and could hobnob with bankers, railroad presidents, and metropolitan merchants… He attended party caucuses and conventions, ran for the state legislature, and sometimes defeated a lawyer or metropolitan businessman in the race for a seat in Congress. In proportion to their numbers, the ranchers… have constituted a highly impressive class.”

Although many of the early capitalists of the great West, especially from Nevada, spent their money principally in the East, others took leadership in promoting the sections in which they had made their fortunes. A railroad pioneer, General William Palmer, built his home at Colorado Springs, founded the town, and encouraged local improvements. Denver, Colorado, owed its first impressive buildings to the civic patriotism of Horace Tabor, a wealthy mine owner. Leland Stanford paid his tribute to California in the endowment of a large university. Colonel William F. Cody, better known as “Buffalo Bill,” began his career by establishing a “boom town,” which ultimately collapsed. Still, he made a substantial amount of money supplying buffalo meat to construction workers. He amassed a fortune through his famous Wild West Show, which he primarily used to promote a Western reclamation scheme.

While the Far West was developing vigorous and aggressive leadership in business, a considerable industrial population was also springing up. Even the cattle ranges and hundreds of farms were conducted like factories in that they were managed by overseers who hired plowmen, harvesters, and cattlemen at regular wages. At the same time, other peculiar features appeared that made a lasting impression on Western economic life. For instance, mining, lumbering, and fruit growing employed thousands of workers during the rush months and turned them out at other times. The inevitable result was an army of migratory laborers wandering from camp to camp, town to town, and ranch to ranch, without fixed homes or established life habits. From this extraordinary condition, a long and lawless conflict arose between capital and labor, giving a distinct color to the labor movement in whole sections of the mountain and coastal states.

By Charles Austin Beard and Mary Ritter Beard; History of the United States, Macmillan, 1921.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2025.

Also See: