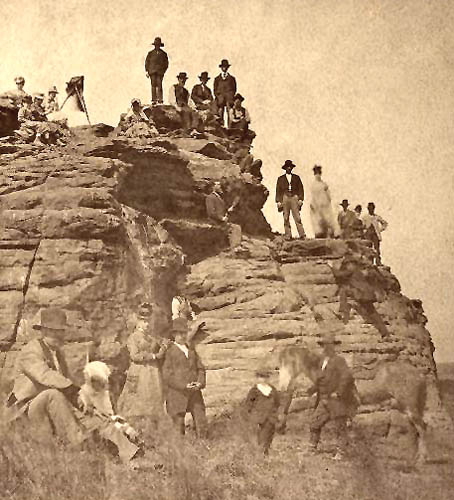

Pawnee Rock on the Santa Fe Trail in Kansas by J.R. Riddle, about 1875.

By Colonel Henry Inman, 1897

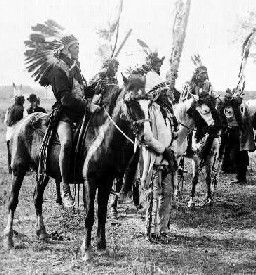

That portion of the great central plains that radiates from Pawnee Rock, including the Big Bend at Fort Larned, 13 miles distant, where that river makes a sudden sweep to the southeast, and the beautiful valley of Walnut Creek, in all its vast area of more than a million square acres, was from time immemorial a sort of debatable land, occupied by none of the Indian tribes, but claimed by all to hunt in; for it was a famous pasturage of the buffalo.

None of the various bands had the temerity to attempt its permanent occupancy, for whenever hostile tribes met there, which was of frequent occurrence, in their annual hunt for their winter’s supply of meat, a bloody battle was sure to ensue.

The region referred to has been the scene of more bloody conflicts between the different Indians of the plains, perhaps, than any other portion of the continent. It was mainly the arena of war to the death when the Pawnee met their hereditary enemies, the Cheyenne.

Pawnee Rock was a spot well calculated by nature to form an important rendezvous point and ambush site for the prowling Indians of the prairies. It often afforded them, especially the once-powerful and murderous Pawnee whose name it perpetuates, a pleasant little retreat from which to watch the passing Santa Fe traders and dash down upon them like hawks to carry off their plunder and their scalps.

The Old Trail wound its course through this once dangerous region, close to the silent Arkansas River and running under the very shadow of the Rock. Now, at this point, it is the actual roadbed of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, so strangely, the past and present transcontinental highways are connected here.

Colonel Henry Inman.

Who, among bearded and grizzled old fellows like myself, have forgotten that most sensational of all the miserably executed illustrations in the geographies of 50 years ago, “The Santa Fe Traders attacked by Indians?” The picture located the scene of the fight at Pawnee Rock, which formed a sort of nondescript shadow in the background of a crudely drawn representation of the dangers of the Trail.

If this once giant sentinel of the plains might speak, what a story it could tell of the events on the beautiful prairie stretching out for miles at its feet!

In the early fall, when the Rock was wrapped in the soft amber haze which is a distinguishing characteristic of the incomparable Indian summer on the plains, or in the spring when the mirage weaves its mysterious shapes, it loomed up in the landscape as if it were a vast mountain, and to the inexperienced eye appeared as if it was the abrupt ending of a well-defined range. But when the frost came and the mists were dispelled, when the thin fringe of timber on Walnut Creek, a few miles distant, had doffed its emerald mantle. The grass had grown yellow and rusty, then in the golden sunlight of winter, the Rock sank to its normal proportions and cut the clear blue of the sky with sharply marked lines.

In the days when the Santa Fe trade was at its height, the Pawnee were the most formidable tribe on the eastern central plains, and the freighters and trappers rarely escaped a skirmish with them either at the crossing of the Walnut, Pawnee Rock, the Fork of the Pawnee or Little and Big Coon Creeks.

Today what is left of the historic hill looks down only upon peaceful homes and fruitful fields, whereas for hundreds of years, it witnessed nothing but battle and death, and almost every yard of brown sod at its base covered a skeleton. In place of the horrid yell of the infuriated Indian as he wrenched off the reeking scalp of his victim, the whistle of the locomotive and the pleasant whirr of the reaping machine is heard, where the death cry of the painted warrior rang mournfully over the silent prairie, the waving grain is singing in beautiful rhythm as it bows to the summer breeze.

Pawnee Rock received its name in a baptism of blood, but there are many versions of the time and sponsors. It was there that Kit Carson killed his first Indian, and from that fight, as he told me himself, the broken mass of red sandstone was given its distinctive title.

It was late in the spring of 1826, when Kit was then a mere boy, only 17 years old, and as green as any boy his age who had never been 40 miles from where he was born. Colonel Ceran St. Vrain, then a prominent agent of one of the great fur companies, was fitting out an expedition destined for the far-off Rocky Mountains, the members of which, all trappers, were to obtain the skins of the buffalo, beaver, otter, mink, and other valuable fur-bearing animals that then roamed in immense numbers on the vast plains or in the hills, and were also to trade with the various tribes of Indians on the borders of Mexico.

Carson joined this expedition, which was composed of 26 mule wagons, some loose stock, and 42 men. The boy was hired to help drive the extra animals, hunt game, stand guard, and make himself generally useful, which included fighting Indians if any were met with on the long route.

The expedition left Fort Osage, Missouri, one bright morning in May in excellent spirits and, in a few hours, turned abruptly to the west on the broad Trail to the mountains. The great plains in those early days were solitary and desolate beyond the power of description; the Arkansas River sluggishly followed the tortuous windings of its treeless banks with a placidness that it was awful in its very silence; and who so traced the wanderings of that stream with no companion but his thoughts, realized in all its intensity the depth of solitude from which Robinson Crusoe suffered on his lonely island. Illimitable as the ocean, the weary waste stretched away until lost in the purple of the horizon, and the mirage created weird pictures in the landscape, distorted distances, and objects that continually annoyed and deceived. Despite its loneliness, however, there was then and ever has been for many men, an infatuation for those majestic prairies that once experienced is never lost. It came to the boyish heart of Kit, who left them but with life and full of years.

There was not much variation in the eternal sameness of things during the first two weeks as the little train moved daily through the grass wilderness, its ever-rattling wheels only intensifying the surrounding monotony. Occasionally, however, a herd of buffalo was discovered in the distance, their brown, shaggy sides contrasting with the never-ending sea of green vegetation around them. Then young Kit and two or three others of the party who were detailed to supply the teamsters and trappers with meat would ride out after them on the best of the extra horses, which were always kept saddled and tied together behind the last wagon for services of this kind. Kit, who was already an excellent horseman and a splendid shot with the rifle, would soon overtake them and topple one after another of their huge fat carcasses over on the prairie until half a dozen or more were lying dead. The tender humps, tongues, and other choice portions were then cut out and put in a wagon which had by that time reached them from the train, and the expedition rolled on.

So they marched for about three weeks, and when they arrived at Walnut Creek Crossing, they saw the first signs of Indians. They had halted for that day — the mules were unharnessed, the campfires lighted, and the men just about to indulge in their refreshing coffee, when suddenly half a dozen Pawnee, mounted on their ponies, hideously painted and uttering the most demoniacal yells, rushed out of the tall grass on the river-bottom, where they had been ambushed, and swinging their buffalo robes, attempted to stampede the herd picketed near the camp. The whole party were on their feet in an instant with rifles in hand, and all the Indians got for their trouble were a few well-deserved shots as they hurriedly scampered back to the river and over into the sandhills on the other side, soon to be out of sight.

The expedition traveled 16 miles the next day and camped at Pawnee Rock, where, after the experience of the evening before, every precaution was taken to prevent a surprise by the Indians. The wagons were formed into a corral so that the animals could be secured in the event of a prolonged fight; the colonel drilled the guards, and every man slept with his rifle for a bed-fellow, for the old trappers knew that the Indians would never remain satisfied with their defeat on Walnut Creek, but would seize the first favorable opportunity to renew their attack.

At dark, the sentinels were placed in position, and to young Kit fell the important post immediately in front of the south face of the Rock, nearly 200 yards from the corral, the others being at prominent points on top and on the open prairie on either side. All who were not on duty had long since been snoring heavily, rolled up in their blankets and buffalo robes, when at about half-past eleven, one of the guards gave the alarm, “Indians!” and ran the mules nearest him into the corral. In a moment, the whole company turned out at the report of a rifle ringing in the clear night air, coming from the direction of the Rock. The men had gathered at the opening to the corral, waiting for developments, when Kit came running in, and as soon as he was near enough, the colonel asked him whether he had seen any Indians. “Yes,” Kit replied, “I killed one of the red devils; I saw him fall!”

The alarm proved false; there was no further disturbance that night, so the party returned to their beds, the sentinels to their several posts, and Kit, of course, to his place in front of the Rock.

Early the following day, before breakfast even, all were so anxious to see Kit’s dead Indian that they went out en masse to where he was still stationed. Instead of finding a painted Pawnee, as was expected, they found the boy’s riding mule dead, shot right through the head.

Kit felt mortified over his ridiculous blunder, and it was long before he heard the last of his midnight adventure and the raid on his mule. But he always liked to tell the “balance of the story,” as he termed it, and this is his version:

“I had not slept any the night before, for I stayed awake watching to get a shot at the Pawnee that tried to stampede our animals, expecting they would return, and I hadn’t caught a wink all day, as I was out buffalo hunting, so I was awfully tired and sleepy when we arrived at Pawnee Rock that evening, and when I was posted at my place at night, I must have gone to sleep leaning against the rocks; at any rate, I was wide enough awake when the cry of Indians was given by one of the guards. I had picketed my mule about twenty steps from where I stood, and I presume he had been lying down; all I remember is that the first thing I saw after the alarm was something rising out of the grass, which I thought was an Indian. I pulled the trigger; it was a center shot, and I don’t believe the mule ever kicked after he was hit!”

The following day, about daylight, a band of Pawnee attacked the train in earnest and kept the little command busy all that day, the next night, and until the following midnight, nearly three whole days, the mules all the time being shut in the corral without food or water. At midnight of the second day, the colonel ordered the men to hitch up and attempt to drive to the crossing of Pawnee Fork, 13 miles distant. They succeeded in getting there, fighting without losing their men or animals. The Trail crossed the creek in the shape of a horseshoe, or rather, in consequence of the double bend of the stream as it empties into the Arkansas River, the road crossed it twice.

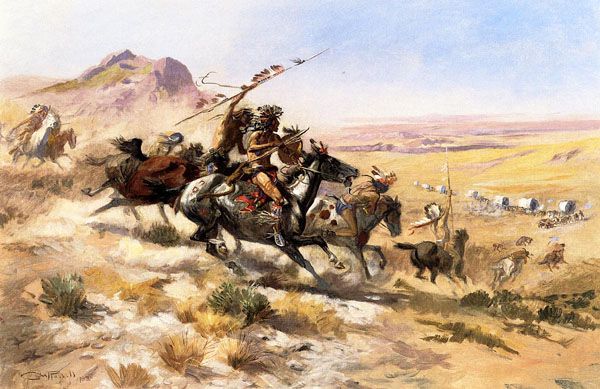

Indian attack on a wagon train by Charles Marion Russell.

In making this passage dangerous because of its crookedness, Kit said many of the wagons were badly mashed up, for the mules were so thirsty that their drivers could not control them.

The train was hardly strung out on the opposite bank when the Indians poured in a volley of bullets and a shower of arrows from both sides of the Trail, but before they could load and fire again, a terrific charge was on them, led by Colonel St.Vrain and Carson. It required only a few moments more to clean out the persistent Indians, and the train went on. During the whole fight, the little party lost four men killed, seven wounded, eleven mules killed (not counting Kit’s), and twenty badly wounded.

Many years ago, very early in the trade with New Mexico, seven Americans were surprised by a large band of Pawnee near the Rock and were compelled to retreat to it for safety. There, without water and with a small quantity of provisions, they were besieged by their blood-thirsty foes for two days when a party of traders coming on the Trail relieved them from their perilous situation and the presence of their enemy. There were several graves on its summit when I first saw Pawnee Rock, but whether they contained the bones of Indians or those of white men, I do not know.

Carson related another terrible fight at the Rock when he first became a trapper. He was not a participant but knew the parties well. About 29 years ago, Kit, Jack Henderson, the agent for the Ute Indians, Lucien B. Maxwell, General Carleton, and myself were camped halfway up the rugged sides of Old Baldy in the Raton Range. The night was intensely cold, although in midsummer, and we were huddled around a little fire of pine knots, more than 7,000 above sea level, close to the snow limit.

Kit, or “the General,” as everyone called him, was in good humor for talking, and we naturally took advantage of this to draw him out; usually, he was the most reticent of men in relating his exploits. A casual remark made by Maxwell opened Carson’s mouth, and he said he remembered one of the “worst difficulties” a man ever got into. So he made a fresh corn-shuck cigarette and related the following, but I have unfortunately forgotten the names of the old trappers who were the principals in the fight.

Two men had been trapping in the Powder River country during one winter with excellent luck, and they got an early start with their furs, which they were going to take to Weston on the Missouri River, one of the principal trading points in those days. They walked the whole distance, driving their pack mules before them, and experienced no trouble until they struck the Arkansas River valley at Pawnee Rock.

There, they were intercepted by a war party of about 60 Pawnee. Both of the trappers were notoriously brave, and both were dead shots. Before they arrived at the Rock, to which they were finally driven, they killed two of the Indians and did not themselves receive a scratch. They had plenty of powder, a pouch full of balls each, and two good rifles. They also had a couple of jackrabbits for food in case of a siege, and the perpendicular walls of the front of the Rock made them a natural fortification, an almost impregnable one against Indians.

They succeeded in securely picketing their animals at the side of the Rock, where they could protect them with their unerring rifles from being stampeded. After the Pawnee had “treed” the two trappers on the Rock, they picked up their dead and packed them off to their camp at the mouth of a little ravine a short distance away. A few moments back, they all came, mounted on fast ponies, with their war paint and other fixings on, ready to renew the fight. They commenced circling the place, coming closer, Indian fashion, every time, until they got within easy rifle range when they slung themselves on the opposite sides of their horses and, in that position, opened fire. Their arrows fell like a hailstorm, but as good luck would have it, none of them struck, and the balls from their rifles were wild, as the Indians in those days were not very good shots; the rifle was a new weapon to them. The trappers, at first, were afraid the Indians would surely try to kill the mules but soon reflected that the Indians believed they had the “dead wood” on them. After being scalped, the mules would come in handy, so they felt satisfied their animals were safe for a while. The men were taking in all the chances, however; both kept their eyes skinned, and whenever one of them saw a stray leg or head, he drew a bead on it, and when he pulled the trigger, its owner tumbled over with a yell of rage from his companions.

Whenever the Indians attempted to carry off their dead, the two trappers took advantage of the opportunity and poured in their shots every time with telling effect.

The trappers stood breathless, clinging to the projections of Rock, and did not realize the fire was so near them until they were struck in the face by pieces of burning buffalo chips carried toward them with the rapidity of the awful wind. They were now severely scared, for it seemed as if they were to be suffocated. They were saved, however, almost miraculously; the sheet of flame passed them twenty yards away, as the wind, fortunately, shifted when the fire reached the foot of the Rock. The darkness was so intense that they did not discover the flame; they only knew they were saved as the clear sky greeted them from behind the dense smoke cloud.

Two of the Indians and their horses were caught in their trap and perished miserably. They had attempted to reach the east side of the Rock to steal around to the other side where the mules were and either cut them loose or crawl up on the trappers while bewildered in the smoke and kill them if they were not already dead. But they had proceeded only a few rods on their little expedition when the terrible darkness of the smoke cloud overtook them and soon the flames, from which there was no possible escape.

All the game on the prairie, which the fire swept over, was killed, too. Only a few buffalo were visible in that region before the fire, but even they were killed. The path of the flames, as was discovered by the caravans that passed over the Trail a few days afterward, was marked with the crisp and blackened carcasses of wolves, coyotes, turkeys, grouse, and every variety of small birds indigenous to the region. Indeed, it seemed as if no living thing it had met escaped its fury. The fire assumed such gigantic proportions and moved rapidly before the wind that even the Arkansas River did not check its path for a moment; it was carried as readily across as if the stream had not been in its way.

The first thought of the trappers on the Rock was for their poor mules. One crawled to where they were and found them badly singed but not seriously injured. The men began to brighten up again when they knew that their means of transportation and themselves were relatively all right, and they took fresh courage, beginning to believe they should get out of their bad scrape after all.

In the meantime, the Indians, except three or four left to guard the Rock to prevent the trappers from getting away, had returned to their camp in the ravine and were concocting some new scheme for the discomfort of the besieged trappers. The latter waited patiently two or three hours for the development of events, snatching a little sleep by turns, which they needed much, for both were worn out by their constant watching. At last, when the sun was about three hours high, the Indians commenced their infernal howling again. Then the trappers knew they had decided upon something, so they were on the alert in a moment to discover what it was and euchre them if possible.

The devils, this time, had tied all their ponies together, covered them with branches of trees that they had gone up on the Walnut for, packed some lodge skins on these, and then, driving the living breastworks before them, moved toward the Rock. They proceeded cautiously but surely, and matters began to look very serious for the trappers. As the strange cavalcade approached, a trapper raised his rifle, and a masked pony tumbled over on the scorched sod dead. As one of the Indians ran to cut him loose, the other trapper took him off his feet with a well-directed shot; he never uttered a groan.

The besieged now saw their only salvation in killing the ponies and demoralizing the Indians so that they would have to abandon such tactics, and quicker than I can tell, they had stretched four more out on the prairie, making it so hot for the Indians that they ran out of range and began to hold a council of war.

Finding that their plan would not work — for as the last pony was shot, the rest stampeded and were running wild over the prairie–the Indians soon went back to their camp again, and the trappers now had a few spare moments in which to take an account of stock. They discovered, much to their chagrin, that they had used up all their ammunition except three or four loads, and despair hovered over them once more.

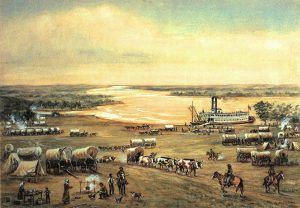

Wagon Train on the Santa Fe Trail.

The Indians did not reappear that evening, and the cause was apparent, for in the distance, a long line of wagons could be seen, one of the large American caravans en route to Santa Fe. The Indians had seen it before the trappers and had cleared out. When the train arrived opposite the Rock, the relieved men came down from their little fortress, joined the caravan, and camped with the Americans that night on the Walnut. While they were resting around their campfire, smoking, and telling of their terrible experience on the top of the Rock, the Indians could be heard chanting the death song while they were burying their warriors under the blackened sod of the prairie.

I witnessed a spirited encounter between a small band of Cheyenne and Pawnee in the fall of 1867. It occurred on the open prairie north of the mouth of the Walnut River, not a great distance from Pawnee Rock. Both tribes were hunting buffalo, and when they, by accident, discovered each other’s presence with a yell that fairly shook the sand dunes on the Arkansas River, they rushed at once into the shock of battle.

That night, in a timbered bend of the Walnut, the victors had a grand dance in which scalps, ears, and fingers of their enemies, suspended by strings to long poles, were essential accessories to their weird orgies around their huge campfires.

One of the most horrible massacres in the history of the Trail occurred at Little Cow Creek in the summer of 1864. In July of that year, a government caravan, loaded with military stores for Fort Union in New Mexico, left Fort Leavenworth for the long and dangerous journey of more than seven hundred miles over the great plains, which Indians infested that season to a degree almost without precedent in the annals of freight traffic.

Mr. H.C. Barret, a contractor with the quartermaster’s department, owned the train. Still, he declined to take the chance of the trip unless the government would lease the outfit or give him an indemnifying bond as assurance against any loss. The chief quartermaster executed the bond as demanded, and Barret hired his teamsters for the hazardous journey, but he found it difficult to induce men to go out that season.

Among those whom he persuaded to enter his employ was a mere boy named McGee, who wandered into Leavenworth a few weeks before the train was ready to leave, seeking work of any description. His parents had died on their way to Kansas, and his arrival at Westport Landing. This emigrant outfit had extended to him shelter and protection, and his utter loneliness was disbanded, so the youthful orphan was thrown on his resources. At that time, the Indians of the great plains, especially along the line of the Santa Fe Trail, were very hostile and continually harassing the freight caravans and stage-coaches of the overland route. Companies of men were enlisting and being mustered into the United States service to go out after the Indians. Young Robert McGee volunteered with hundreds of others for the dangerous duty. The government needed men badly, but McGee’s youth militated against him, and he was below the required stature, so the mustering officer rejected him.

In hunting for teamsters to drive his caravan, Mr. Barret came across McGee, who, supposing that he was hired as a government employee, accepted Mr. Barret’s offer.

By the last day of June, the caravan was all ready, and on the morning of the next day, July 11, the wagons rolled out of the fort, escorted by a company of United States troops from the volunteers referred to.

The caravan wound its weary way over the lonesome trail with nothing to relieve the monotony save a few skirmishes with the Indians. No casualties occurred in these insignificant battles, the Indians being afraid to venture too near on account of the presence of the military escort.

On July 18, the caravan arrived near Fort Larned, Kansas. The proximity of that military post was supposed to be a sufficient guarantee against any attack by the Indians, so the train’s men became careless. As the day was excessively hot, they went into camp early in the afternoon, the escort remaining in a bivouac about a mile in the rear of the train.

About five o’clock, a hundred and fifty painted Indians, under the command of Little Turtle of the Brule Sioux, swooped down on the unsuspecting caravan while the men were enjoying their evening meal. Not a moment was given for them to rally to the defense of their lives and all belonging to the outfit, except for one boy; not a soul came out alive.

The teamsters were shot dead, and their bodies mutilated. After their successful raid, the Indians destroyed everything they found in the wagons, tearing the covers into shreds, throwing the flour on the trail, and winding up by burning everything combustible.

On the same day, the commanding officer of Fort Larned had learned from some of his scouts that the Brule Sioux were on the warpath, and the chief of the scouts, with a handful of soldiers, was sent out to reconnoiter. They soon struck the trail of Little Turtle and followed it to the scene of the massacre on Cow Creek, arriving there only two hours after the Indians had finished their devilish work. Dead men were lying about in the short buffalo grass, which had been stained and matted by their flowing blood, and the agonized posture of their bodies told far more forcibly than any language the tortures that had come before a welcome death. All had been scalped; all had been mutilated in that nameless manner that seems to delight the brutal instincts of the North American Indian.

Moving slowly from one to the other of the lifeless forms, which still showed the agony of their death throes, the chief of the scouts came across the bodies of two boys, both of whom had been scalped and shockingly wounded, besides being mutilated, yet, strange to say, both of them were alive. As tenderly as the men could lift them, they were conveyed back to Fort Larned and given in charge of the post surgeon. One of the boys died a few hours after he arrived in the hospital, but the other, Robert McGee, slowly regained his strength and came out of the ordeal in reasonably good health.

Young McGee related the story of the massacre after he was able to talk while in the hospital at the fort, for he had not lost consciousness during the suffering to which the Indians subjected him.

He was compelled to witness the tortures inflicted on his wounded and captive companions, after which he was dragged into the presence of the chief, Little Turtle, who determined that he would kill the boy with his own hands. He shot him in the back with his revolver, having first knocked him down with a lance handle. He then drove two arrows through the unfortunate boy’s body, fastening him to the ground, and stooping over his prostrate form, ran his knife around his head, lifting 64 square inches of his scalp, trimming it off just behind his ears.

Believing him dead by that time, Little Turtle abandoned his victim, but the other Indians, as they went by his supposed corpse, could not resist their infernal delight in blood, so they thrust their knives into him and bored great holes in his body with their lances. After the Indians had done all that their devilish ingenuity could contrive, they exultingly rode away, yelling as they bore off the reeking scalps of their victims and drove away the hundreds of mules they had captured.

When the tragedy ended, the soldiers, who had witnessed the whole diabolical transaction from their vantage point, came up to the bloody camp by order of their commander to learn whether the teamsters had driven away from their assailants. They saw too late what their cowardice had allowed to take place. The officer in command of the escort was dismissed from the service as he could not give any satisfactory reason for not going to the rescue of the caravan he had been ordered to guard.

By Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Also See:

Pawnee Rock Historical Landmark

Hidden Treasure at Pawnee Rock

Excerpted from the book, The Old Santa Fe Trail, by Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Though the content of Inman’s writing is essentially the same, it is not verbatim, as it has been truncated, a few additions made (as to states and names), and edited for the modern reader. Henry Inman was well known as an officer in the U.S. Army and an author dealing with subjects of the Western plains. During the Civil War, Inman was a Lieutenant Colonel, and afterward, he won the distinction of magazine writer. He wrote several books, including his Old Santa Fe Trail, Great Salt Lake Trail, The Ranch on the Ox-hide, and other similar books dealing with the subjects he knew so well. Colonel Inman left several unfinished manuscripts at his death in Topeka, Kansas, on November 13, 1899.