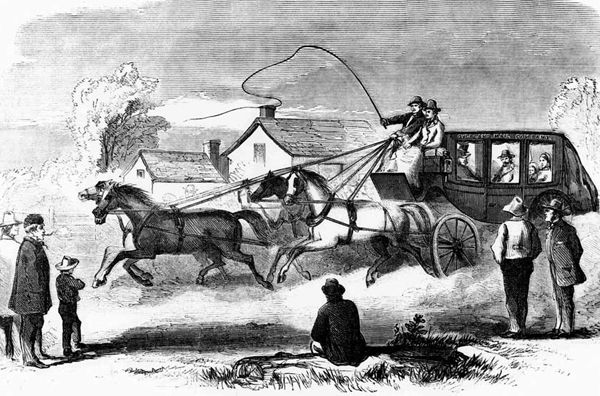

Stagecoach on the Overland Trail near Laramie, Wyoming.

By Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool, 1922, with additional edits/information by Legends Of America.

The Overland Trail, also known as the Overland Stage Line, was a stagecoach and wagon road in the American West. Explorers and trappers had used Portions of the route since the 1820s, especially along what would later become the California, Oregon, and Mormon Trails. Ben Holladay established the Overland Trail Mail route in 1862, following the Pony Express Trail closely.

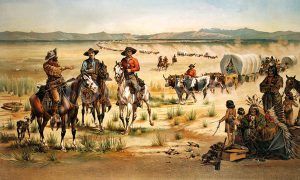

As the Oregon Trail widened and extended deeper into the mountains and onto the plains, many people eventually did not have the Pacific Coast in mind as their destination. Gradually, men and families unyoked their oxen, unharnessed the horses, and prepared to make a home in those sections most attractive in what was named and known as “The Great American Desert.” As more people came to claim free land, isolated towns sprang up, and civilization expanded West. However, most of these new settlements were camps in the mining districts.

The necessity for safer and better transportation of supplies to these mining camps became most urgent. One of these places was Sacramento, at the end of the California branch of the Oregon Trail and the center of the early gold excitement in California.

New trails were blazed after more gold was found in the inland territories of Idaho, Utah, Montana, and Colorado. The government did not construct these, but they were side routes from the main trails made by the men seeking gold. As a logical outcome of the constant need for food, clothing, and tools, an organized movement transferred supplies from the Missouri River to the wealth-bearing mountains.

Over the Oregon Trail, supply caravans or wagon trains made their way through a country that was once described as “only fit for prairie dogs and Indians.” Most people who came to the mountains in the early days did not go into agriculture or other occupations; they went there to find gold or silver. To have things to eat and wear, tools for digging the ore, horses and mules to operate the heavy work of the mines, and food for these working animals made the commerce of freighting an absolute necessity. Wagon traffic was to supply necessities and luxuries for the West, on the isolated portions of the plains or in the hidden passes in the mountains.

Before regular freight trains were established, individual families on their way to the West banded together to protect themselves against hostile Indians. How commerce could be extended to those who had pushed into the unoccupied lands was a perplexing consideration for those who were to make the journey and the companies involved in transporting business.

Finally, the people on the Pacific coast demanded that the government take the necessary steps to establish a mail route across the mountains and plains. When Utah was created as a territory, the people had to wait for the official Act of Congress from September 1850 to January 1851 because the documents traveled via the Panama route to California and then east back to Utah. In July 1850, the first monthly mail route was established between Independence, Missouri, and Salt Lake City, Utah, where it met an extension line going to California.

Alexander Majors, in 1858, when helping the government fill its contracts to carry supplies to Utah, used 3,500 to 4,000 men, 1,000 mules, and more than 40,000 oxen. In May 1859, people such as Horace Greeley, Henry Villiard, and Albert D. Richardson rode into Denver on Majors’ first stagecoach, “Horsepower Pullman,” making 665 miles in six days, a distance that previously had been covered in 22 days. This first stagecoach made the 600-mile trip between Denver and Salt Lake “without a single town, hamlet, or house being encountered on the way,” with a few necessary stage stations.

Efficient mail service to the far West also began in 1858, when the Butterfield Overland Mail route was established. The mail was first sent only semi-weekly, but soon changed to six days per week. This route was 2,759 miles long, traveling through El Paso, Texas, to Yuma, Arizona, and then to California, making the journey under favorable conditions in 23-25 days. The letters cost 10¢ per half an ounce, and passengers paid a fare of $100. The one great advantage of this route was that it was so far south, avoiding the snow found on northern trails.

The Butterfield stage starts its journey in Tipton, Missouri.

This stage line was 40% longer than any other established stage line, an expensive affair from the mere fact of its unusual length. The road’s equipment was also costly, containing 100 Concord coaches, 1,000 horses, 500 mules, 750 men, and 150 drivers. When the Civil War began in 1861, it forced the government to change the route to a more northern territory. They selected the Overland Trail as a new route from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Placerville, California, which became known as the “Central Route.”

The Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company then ran mail stages over the Oregon Trail, operating simultaneously east and West. Each stage took 18 days, compared to 25 days on the southern route. In the early 1860s, the fare for the trip across the plains from Atchison, Kansas, to Placerville, California, was $600, including 25 pounds of baggage. Any excess baggage cost $1 per pound.

However, the lumbering stages were too slow in transporting mail to California’s impatient, news-hungry people, who demanded a faster method.

As a result of persistent demand, thanks to the efforts of William H. Russell, the Pony Express was established, carrying mail to California in just 10 days. The road for the Pony Express, from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Placerville, California, a distance of almost 2,000 miles, followed the Oregon and Mormon Trails to Salt Lake City and the Central Nevada Route to Sacramento. The horses employed were all small and of a western breed. There were 500 of them, and the riders were light in weight to match their mounts.

The company operating the Pony Express had 200 station keepers and 190 stations. Eighty riders were given only two minutes to change horses and transfer their saddlebags of mail. The stations were nine to 15 miles apart, depending on the water’s proximity.

Letters, costing $5 a half-ounce, were limited to 15 pounds for the average rider and equally divided into two flat leather, securely locked mail pouches. During the Pony Express’s operation from April 3, 1860, to October 24, 1861, the mail was lost once when it was stolen by Indians.

The relay riders’ best time with this overland service was seven days and 17 hours when President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural message was whisked over the route. There is no more picturesque achievement of the plains than the operation of the Pony Express, which shortened the time for Pacific mail service, thus bringing the people of the coast many days nearer to their former homes and the national government.

First Ride of the Pony Express.

General John Reynolds, when at his winter headquarters in 1859-60, not far from the junction of Deer Creek with the North Platte River on the south side of the Oregon Trail, was one of the first West of Fort Laramie, Wyoming, to receive mail utilizing the Pony Express.

“The Pony Express was established while we were in winter quarters, and by it, we received interesting news several times, but it was three days old. The sight of a solitary horseman galloping along the road was in itself nothing remarkable, but when we remember that he was one of a series stretching across the continent and forming a continuous chain for two thousand miles through an almost absolute wilderness, the undertaking was justly ranked among the events of the age, and the most striking triumph of American energy.”

— General John Reynolds

However, the Pony Express lasted only a year before Central Overland, California, and Pikes Peak Express Company went bankrupt, and the assets were sold to Ben Holladay.

In 1861, Holladay was awarded the Postal Department contract for overland mail service between the end of the railroad’s western terminus in Missouri, Kansas, and Salt Lake City. The Overland Mail Company and other stage lines were given service from Utah to California.

With the discovery of gold in Colorado and the consequent growth of the city of Denver, Holladay changed the Overland Trail to the West, using the banks of the South Platte River, as well as those of the North Platte, as a thoroughfare descending into Colorado before looping back up to southern Wyoming and rejoining the Oregon Trail at Fort Bridger, Wyoming. Due to Indian uprisings occurring on the Oregon Trail farther north through central Wyoming along the Sweetwater-South Pass route, the new route became the only emigrant route on which the US Government would allow travel. Consequently, it was the principal corridor to the West from 1862 to 1868.

Between 1861 and 1866, Holaday operated about 5,000 miles of stagecoaches daily, having equipment of 500 coaches and express wagons, 500 freight wagons, 5,000 horses and mules, and numerous oxen. The cost of caring for this company’s stock averaged $1 million annually, while equipping and running the line for the first year incurred an additional expense of $2,425,000. After five years of freighting, Holladay sold his entire business to the Wells Fargo Company, which remained active in that transportation line until 1869, when the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads were completed. Holladay, in 1865, to help out the Overland Route to the Montana goldfields, established a branch line of his road from Fort Hall, Idaho, north to Virginia City, Montana. In addition to freight, Holladay carried the mail for the government during the Civil War, receiving one million dollars annually. Statistics show that in 1861, over 21 million pounds of freight went west from the shipping points of Atchison, Kansas, which required the use of 4,917 wagons, 6,164 mules, 27,685 oxen, and 1,256 men to transport it to the plains.

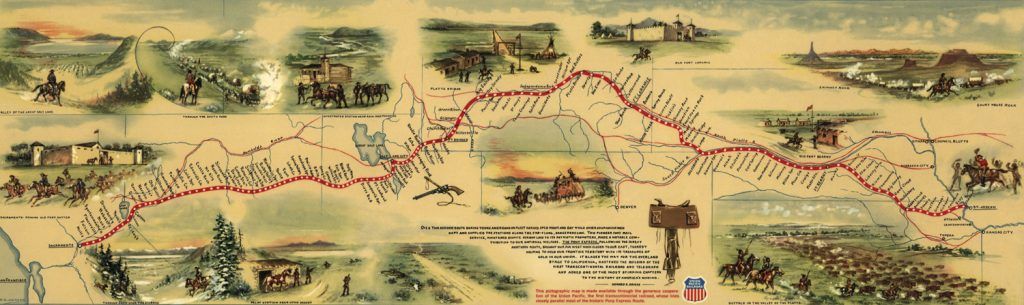

The Overland Trail closely followed the Pony Express Route, drawn by William Henry Jackson in 1860.

For many years, Russell, Majors, and Waddell, government contractors who transported military supplies to the forts along the trails, used their trail-freighting train, which consisted of 6,250 oversized wagons with a carrying capacity of 6,000 pounds each, and 75,000 oxen. If placed one in front of the other, this array of transportation facilities would have covered a stretch of 40 miles along the trail. After a reliable freighting system was in place, it was not uncommon to see over 1,000 of these patients plodding ox teams stretched across the plains each week, with wagons loaded many feet beyond the sideboards.

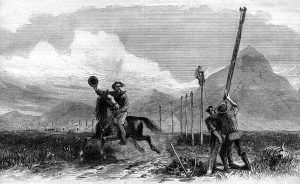

This drawing by George M. Ottinger appeared in Harper’s Weekly in 1867.

The extension of the telegraph line across the continent, under the management of Edward Creighton, in 1861, was the undoing of the Pony Express, which had been inaugurated to have a better and more rapid mail service from the Missouri River to San Francisco. The telegraph was put into operation on October 24, 1861, when the first transcontinental message was flashed over the line. Thus, an unprecedented step was taken in binding and uniting the Missouri River with the Pacific Ocean. This telegraph line ran parallel with and over the Oregon Trail. It soon became to the Indians a symbol of the white man’s despotism and his determination to finally possess the country through which the singing wires had spun their way to the lands of the mining camps and new mountain homes.

Two stage and telegraph lines from the Missouri River were established, one from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to Fort Kearny, Nebraska, and the other from Omaha to Fort Kearny, Nebraska.

At Fort Kearny, the lines consolidated, extending up the Platte Valley as far as Julesburg, Colorado, a prominent stage station near the mouth of Lodgepole Creek, where it emptied into the Platte River. The lines again separated at this characteristically busy border town, with the main telegraph line heading northwest to Fort Laramie, Wyoming, and beyond to South Pass and Utah. In contrast, the stage line went southwestward to Denver, Colorado, using the South Platte River. From Denver, the coaches went north to Fort Collins, then to Virginia Dale, Colorado, across the Laramie Plains, to Fort Halleck, Elk Mountain, Bridger’s Pass, Bitter Creek, and on to Fort Bridger. They then headed to Utah, California, Oregon, and Montana. Just east of Fort Bridger, the Oregon Trail and the Overland Trail united and became one.

The route of the stage lines crossing these savagely contested lands had stage stations situated about every 12 miles along their length. In comparison, government troops were posted along the route at specially constructed forts or blockhouses, spaced about 100 miles apart. The scarcity of soldiers, particularly during the Civil War, for this dangerous duty put the lives of the few who served in extreme danger. Only a few armed and trained men were distributed at each station. In addition to these fortified buildings, along the way were the occasional farmer and rancher, relay stations for changing horses, and eating houses.

The shrewd Ben Holladay maintained a virtual monopoly of the Overland Stage line until 1866, when he sold out. Well aware that the inevitable completion of the new Transcontinental Railroad would eliminate the need for stagecoach transportation, Holladay was fortunate to sell the route, the equipment, and the contracts to Wells Fargo. The overland mail continued for another 2 1/2 years along the Overland Trail until the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific railroads met at Promontory Point, Utah, in 1869, eliminating the need for mail service via the stagecoach.

The Overland Trail was most heavily used in the 1860s as an alternative route to the Oregon, California, and Mormon trails through central Wyoming.

It was a colossal business to supply the things most needed for the towns and cities that were springing up in the West, and the Oregon Trail became broader and deeper. This mighty traffic scarred the face of the trail to the West so deeply that in many places, for miles, there remained discernible traces of the heavy traffic of this period, even after more than 50 years of disuse.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2025.

Also See:

Adventures & Tragedies on the Overland Trail

Stagecoaches of the American West

Stagecoach Kings (Lines) & Drivers

Wagons and Stagecoaches Photo Gallery

Source: Much of this article was written by Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool, Western historians in the early 20th century. This account was excerpted from their book, The Bozeman Trail: Historical Accounts of the Blazing of the Overland Routes Into the Northwest, published by the Arthur H. Clark Company in 1922. However, the article as it appears here has been heavily edited for spelling and grammatical corrections, truncated, and additional information has been added.

Other Sources:

Overland Trail

Wikipedia