Wagons With Families.

“My father, with tears in his eyes, tried to smile as one friend after another grasped his hand in a last farewell. Mama was overcome with grief. At last, we were all in the wagons. The drivers cracked their whips. The oxen moved slowly forward, and the long journey had begun.”

— Virginia Reed, daughter of James Reed

On April 16, 1846, nine covered wagons left Springfield, Illinois, on the 2,500-mile journey to California in what would become one of the greatest tragedies in the history of westward migration.

The originator of this group was James Frasier Reed, an Illinois businessman eager to build a greater fortune in the rich land of California. Reed also hoped that his wife, Margaret, who suffered from terrible headaches, might improve in the coastal climate. Reed had recently read the book The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California by Landsford W. Hastings, who advertised a new shortcut across the Great Basin. This new route enticed travelers by advertising that it would save the pioneers 350-400 miles on easy terrain. However, Reed did not know that the Hastings Route had never been tested. It was written by Hastings, who envisioned building an empire at Sutter’s Fort (now Sacramento). It was this falsified information that would lead to the doom of the Donner Party.

Reed soon found others seeking adventure and fortune in the vast West, including the Donner family, Graves, Breens, Murphys, Eddys, McCutcheons, Kesebergs, and the Wolfingers, as well as seven teamsters and several bachelors. The initial group included 32 men, women, and children.

With James and Margaret Reed with their four children, Virginia, Patty, James, and Thomas, as well as Margaret’s 70-year-old mother, Sarah Keyes, and two hired servants. Though Sarah Keyes was so sick with consumption that she could barely walk, she was unwilling to be separated from her only daughter. However, the successful Reed was determined his family would not suffer on the long journey. His wagon was an extravagant two-story affair with a built-in iron stove, spring-cushioned seats, and bunks for sleeping. Taking eight oxen to pull the luxurious wagon, Reed’s 12-year-old daughter Virginia dubbed it “The Pioneer Palace Car.”

In nine brand-new wagons, the group estimated the trip would take four months to cross the plains, deserts, mountain ranges, and rivers in their quest for California. Their first destination was Independence, Missouri, the main jumping-off point for the Oregon and California Trails.

Also in the group were the families of George and Jacob Donner. George Donner was a successful 62-year-old farmer who had migrated five times before settling in Springfield, Illinois, along with his brother Jacob. Adventurous, the brothers decided to make one last trip to California, which would unfortunately be their last.

With George were his third wife, Tamzene, their three children, Frances, Georgia, and Eliza, and George’s two daughters from a previous marriage, Elitha and Leanna. Jacob Donner and his wife, Elizabeth, brought their five children, George, Mary, Isaac, Samuel, and Lewis, as well as Mrs. Donner’s two children from a previous marriage, Solomon and William Hook.

Also along with them were two teamsters, Noah James and Samuel Shoemaker, and a friend named John Denton. At the bottom of Jacob Donner’s saddlebag was a copy of Lansford Hastings’s Emigrant’s Guide, with its tantalizing talk of a faster route to the garden of the earth.

Ironically, on the day that the Illinois party headed west from Springfield, Lansford Hastings prepared to head east from California to see what the shortcut he had written about was like.

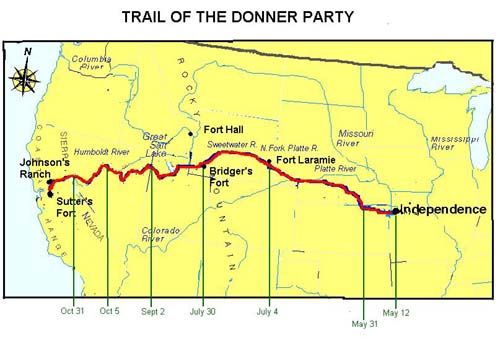

About three weeks later, the wagon train reached Independence, Missouri, where it re-supplied. The next day, May 122, 1846, it headed west again in the middle of a thunderstorm. A week later, it joined a large wagon train captained by Colonel William H. Russell that was camped on Indian Creek about 100 miles west of Independence. Along the journey, others joined the group until its size numbered 87.

Donner Party Map, courtesy of Donner Party Diary

On May 25, the train was held for several days by high water at the Big Blue River near present-day Marysville, Kansas. It was here that the train would experience its first death when Sarah Keyes died and was buried next to the river. After building ferries to cross the water, the party was on their way again, following the Platte River for the next month.

Along the way, William Russell resigned as the captain of the wagon train, and a man named William M. Boggs assumed the position. Encountering a few problems along the trail, the pioneers reached Fort Laramie just one week behind schedule on June 27, 1846.

At Fort Laramie, James Reed ran into an old friend from Illinois named James Clyman, who had just traveled the new route eastwardly with Lansford Hastings. Clyman advised Reed not to take the Hastings Route, stating that the road was barely passable on foot and would be impossible with wagons; he also warned Reed of the great desert and the Sierra Nevadas. Though he strongly suggested that the party take the regular wagon trail rather than this new false route, Reed would later ignore his warning in an attempt to reach their destination more quickly.

Joined by other wagons in Fort Laramie, the pioneers were met by a man carrying a letter from Lansford W. Hastings at the Continental Divide on July 11. The letter stated that Hastings would meet the emigrants at Fort Bridger and lead them on his cutoff, which passed south of the Great Salt Lake instead of detouring northwest via Fort Hall (present-day Pocatello, Idaho).

The letter successfully allayed any fears the party might have had regarding the Hastings cutoff. On July 19, the wagon train arrived at the Little Sandy River in present-day Wyoming, where the trail parted into two routes – the northerly known route and the untested Hastings Cutoff. Here, the train split, with most of the large caravan taking the safer route. The group, preferring the Hastings route, elected George Donner as their captain and soon began the southerly route, reaching Fort Bridger on July 28. However, upon their arrival at Fort Bridger of Lansford Hastings, there was no sign, only a note left with other emigrants resting at the fort. The note indicated that Hastings had left with another group and that later travelers should follow and catch up. Jim Bridger and his partner Louis Vasquez assured the Donner Party that the Hastings Cutoff was a good route. Satisfied, the emigrants rested for a few days at the fort, repairing their wagons and preparing for the rest of what they thought would be a seven-week journey.

On July 31, the party left Fort Bridger, joined by the McCutchen family. The group now numbered 74 people in 20 wagons and made good progress at 10-12 miles per day for the first week.

On August 6, the party reached the Weber River after passing through Echo Canyon. They stopped when they found a note from Hastings advising them not to follow him down Weber Canyon, as it was virtually impassable, but rather to take another trail through the Salt Basin.

While the party camped near modern-day Henefer, Utah, James Reed and two other men forged ahead on horses to catch up with Hastings. Finding the party at the south shore of the Great Salt Lake, Hastings accompanied Reed partway back to point out the new route, which he said would take them about one week to travel. In the meantime, the Graves family caught up with the Donner Party, which now numbered 87 people in 23 wagons. Taking a vote among the party members, the group decided to try the new trail rather than backtracking to Fort Bridger.

On August 11, the wagon train began the arduous journey through the Wasatch Mountains, clearing trees and other obstructions along the new path of their journey. Initially, the wagon train was lucky to make even two miles per day, taking them six days to travel eight miles. Along the way, they discovered that some of their wagons would have to be abandoned, and before long, morale began to sink, and the pioneers blamed Lansford Hastings adamantly. By the time they reached the shore, they also blamed James Reed.

On August 25, the caravan lost another member, Luke Halloran, who died of consumption near present-day Grantsville, Utah. Fear began to set in about this time as provisions ran low, and time was against them. In the 21 days since reaching the Weber River, they had moved just 36 miles.

Five days later, on August 30, the group began to cross the Great Salt Lake Desert, believing the trek would take only two days, according to Hastings. However, they didn’t know that the desert sand was moist and deep, where wagons quickly got bogged down, severely slowing their progress. On the third day in the desert, their water supply was nearly exhausted, and some of Reed’s oxen ran away. When they finally reached the end of the grueling desert five days later, on September 4, the emigrants rested near the base of Pilot Peak for several days. On their 80-mile journey through the Salt Lake Desert, they had lost 32 oxen; Reed was forced to abandon two of his wagons, and the Donners and Louis Keseberg lost one wagon each.

Great Salt Lake Desert, Utah.

On the far side of the desert, an inventory of food was taken and found to be less than adequate for the 600-mile trek still ahead. Ominously, snow powdered the mountain peaks that very night. They reached the Humboldt River on September 26.

Realizing that the difficult journey through the mountains and the desert had depleted their supplies, two young men traveling with the party, William McCutcheon and Charles Stanton were sent to Sutter’s Fort, California, to bring back supplies.

From September 100 through the 25, the party followed the trail into Nevada around the Ruby Mountains, finally reaching the Humboldt River on September 26. It was here that the “new” trail met Hasting’s original path. Having traveled an extra 125 miles through strenuous mountain terrain and desert, the disillusioned party’s resentment of Hastings and, ultimately, Reed increased tremendously.

The Donner Party soon reached the junction with the California Trail, about seven miles west of present-day Elko, Nevada, and spent the next two weeks traveling along the Humboldt River. As the party’s disillusionment increased, tempers began to flare.

On October 5 at Iron Point, two wagons became entangled, and John Snyder, a teamster of one of the wagons, began to whip his oxen. Infuriated by the teamster’s treatment of the oxen, James Reed ordered the man to stop, and when he wouldn’t, Reed grabbed his knife and stabbed the teamster in the stomach, killing him. The Donner Party wasted no time in administering their own justice. Though member Lewis Keseberg favored hanging for James Reed, the group voted to banish him instead. After leaving his family, Reed was last seen riding off to the west with Walter Herron.

The Donner Party continued to travel along the Humboldt River, and their remaining draft animals were exhausted. To spare the animals, everyone who could walk. Two days after the Snyder killing, onOctober 77, Lewis Keseberg turned out a Belgian man named Hardcoop, who had been traveling with him. The old man, who could not keep up with the rest of the party with his severely swollen feet, began to knock on other wagon doors, but no one would let him in. He was last seen sitting under a large sagebrush, completely exhausted, unable to walk, worn out, and was left there to die.

The terrible ordeals of the caravan continued to mount when, on October 12, their oxen were attacked by Paiute Indians, killing 21, one of them with poison-tipped arrows, further depleting their draft animals.

Continuing to encounter multiple obstacles, on October 16, they reached the gateway to the Sierra Nevada on the Truckee River, almost wholly depleted of food supplies. Miraculously, just three days later, on October 19, one of the men the party had sent on to Fort Sutter — Charles Stanton, returned laden with seven mules loaded with beef and flour, two Indian guides, and news of a clear but difficult path through the Sierra Nevada. Stanton’s partner, William McCutchen, had fallen ill and remained at the fort. The caravan camped for five days, 50 miles from the summit, resting their oxen for the final push. This decision to delay their departure was one more of many that would lead to their tragedy.

On October 28, an exhausted James Reed arrived at Sutter’s Fort, where he met William McCutchen, who had recovered. The two men began preparations to return home for their families.

In the meantime, while the wagon train continued to the base of the summit, George Donner’s wagon axle broke, and he fell behind the rest of the party. Twenty-two people, including the Donner family and their hired men, stayed behind while the wagon was repaired. Unfortunately, while cutting timber for a new axle, a chisel slipped, and Donner cut his hand badly, causing the group to fall further behind.

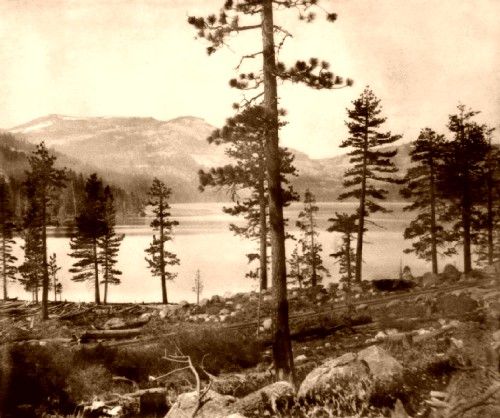

Donner Lake, 1866.

Snow began to fall as the rest of the party continued to what is now known as Donner’s Lake. Stanton and the two Indians traveling ahead made it as far as the summit but could go no further. Hopeless, they retraced their steps where five feet of new snow had already fallen.

With the Sierra Pass just 12 miles beyond, the wagon train, after attempting to make the pass through the heavy snow, finally retreated to the eastern end of the lake, where level ground and timber were abundant. At the lake stood one existing cabin, and realizing they were stranded, the group built two more cabins, sheltering 59 people in hopes that the early snow would melt and allow them to continue their travels.

The 22 people with the Donners were about six miles behind at Alder Creek. Hastily, as the snow continued, the party built three shelters from tents, quilts, buffalo robes, and brush to protect themselves from the harsh conditions.

At Donner Lake, two more attempts were made to get over the pass in 20 feet of snow until they finally realized they were snowbound for the winter. More small cabins were constructed, many shared by more than one family. The weather and their hopes were not to improve. Over the next four months, the remaining men, women, and children would huddle together in cabins, makeshift lean-tos, and tents.

Meanwhile, Reed and McCutchen had headed back into the mountains, attempting to rescue their stranded companions. Two days after they started, it began to rain. As the elevation increased, the rain turned to snow, and twelve miles from the summit, the pair could go no further. Caching their provisions in Bear Valley, they returned to Sutter’s fort, hoping to recruit more men and supplies for the rescue. However, the Mexican War had drawn away the able-bodied men, forcing any further rescue attempts to wait. Not knowing how many cattle the emigrants had lost, the men believed the party would have enough meat to last them several months. On Thanksgiving, it began to snow again, and the pioneers at Donner Lake killed the last of their oxen for food on November 29.

The next day, five more feet of snow fell, and they knew that any plans for a departure were dashed. Many of their animals, including Sutter’s mules, had wandered off into the storms, and their bodies were lost under the snow. A few days later, their last few cattle were slaughtered for food, and the party began eating boiled hides, twigs, bones, and bark. Some of the men tried to hunt with little success.

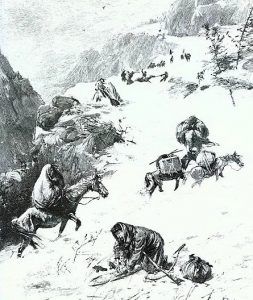

On December 15, Balis Williams died of malnutrition, and the group realized that something had to be done before they all died. The next day, five men, nine women, and one child departed on snowshoes for the summit, determined to travel the 100 miles to Sutter’s Fort. However, the group faced a challenging ordeal with only meager rations and already weak from hunger. On the sixth day, their food ran out, and for the next three days, no one ate while they traveled through grueling high winds and freezing weather. One member of the party, Charles Stanton, snow-blind and exhausted, was unable to keep up with the rest of the party and told them to go on. He never rejoined the group. A few days later, the party was caught in a blizzard and had difficulty getting and keeping a fire lit. Antonio, Patrick Dolan, Franklin Graves, and Lemuel Murphy soon died, and in desperation, the others resorted to cannibalism.

Living off the bodies of those who died along the path to Sutter’s Fort, the snowshoeing survivors were reduced to seven by the time they reached safety on the western side of the mountains on January 19, 1847. Only two of the ten men survived, including William Eddy and William Foster, but all five women lived through the journey. Of the eight dead, seven had been cannibalized. Immediately, messages were dispatched to neighboring settlements, and area residents rallied to save the rest of the Donner Party.

February 5, the first relief party of seven men left Johnson’s ranch, and the second, headed by James Reed, left two days later. On February 19, the first party reached the lake and found what appeared to be a deserted camp. Then, the ghostly figure of a woman appeared. Twelve of the emigrants were dead, and of the 48 remaining, many had gone crazy or were barely clinging to life. However, the nightmare was by no means over. Not everyone could be taken out at once, and since no pack animals could be brought in, few food supplies were brought in. The first relief party soon left with 23 refugees, but during the party’s travels back to Sutter’s Fort, two more children died. En route down the mountains, the first relief party met the second relief party, who came the opposite way, and the Reed family was reunited after five months.

On March 11, the second relief party finally arrived at the lake, finding grisly evidence of cannibalism. The next day, they arrived at Alder Creek to find that the Donners had also resorted to cannibalism. On March 33, Reed left the camp with 17 starving emigrants, who were caught in another blizzard just two days later. When it cleared, Isaac Donner had died, and most of the refugees were too weak to travel. Reed and another rescuer, Hiram Miller, took three refugees with them, hoping to find food they had stored on the way up. The rest of the pioneers stayed at what would become known as “Starved Camp.”

On March 12, the third relief led by William Eddy and William Foster reached Starved Camp, where Mrs. Graves and her son Franklin had also died. The three bodies, including that of Isaac Donner, had been cannibalized. The next day, they arrived at the lake camp to find that both of their sons had died. On March 14, they arrived at the Alder Creek camp to find George Donner was dying from an infection in the hand that he had injured months before. His wife Tamzene, though in comparatively good health, refused to leave him, sending her three little girls on without her. The relief party soon departed with four more members, leaving those too weak to travel. Two rescuers, Jean-Baptiste Trudeau, and Nicholas Clark, were left behind to care for the Donners but soon abandoned them to catch up with the relief party.

1866 photo of Alder Creek stumps cut by Donner party. The stumps represent the depth of the snow at the time.

A fourth rescue party set out in late March but was soon stranded in a blinding snowstorm for several days. On April 17, the relief party reached the camps to find only Louis Keseberg alive among the mutilated remains of his former companions. Keseberg was the last member of the Donner Party to arrive at Sutter’s Fort on April 29. Rescuing the surviving Donner Party took two months and four relief parties.

In the Donner Party tragedy, two-thirds of the men in the party perished, while two-thirds of the women and children lived. Forty-one individuals died, and 46 survived. In the end, five died before reaching the mountains, 35 perished either at the mountain camps or trying to cross the mountains, and one died just after reaching the valley. Many of those who survived lost their toes to frostbite.

The story of the Donner tragedy quickly spread across the country. Newspapers printed letters and diaries and accused the travelers of bad conduct, cannibalism, and even murder. The surviving members had differing viewpoints, biases, and recollections, so what happened was unclear. Some blamed the power-hungry Lansford W. Hastings for the tragedy, while others blamed James Reed for not heeding Clyman’s warning about the deadly route.

After the publicity, emigration to California fell sharply, and Hastings’ cutoff was abandoned. Then, in January 1848, gold was discovered at John Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, and gold-hungry travelers began to rush out West once again. By late 1849, more than 100,000 people had come to California searching for gold near the streams and canyons where the Donner Party had suffered.

Donner Lake, named for the party, is a popular mountain resort near Truckee, California. The Donner Camp has been designated a National Historic Landmark and has been the site of recent archeological excavations.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Also See:

Danger and Hardship on the Oregon Trail

Tales and Trails of the American Frontier

Westward Expansion & Manifest Destiny

See Sources.