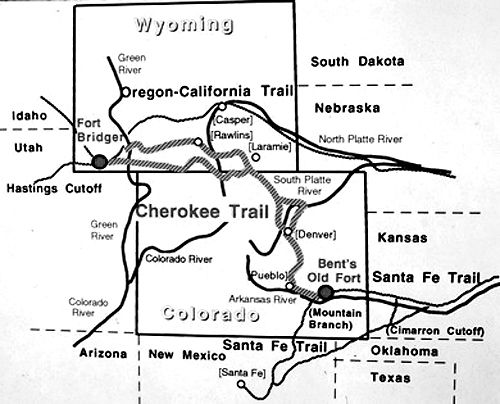

Cherokee Trail Map, courtesy Playground Trail.

The Cherokee Trail was a historic overland route through Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, used from the late 1840s to the early 1890s.

The trail route ran northwest of the Grand River near present-day Salina, Oklahoma, to strike the Santa Fe Trail at McPherson, Kansas. From there, it followed the Santa Fe Trail west, then turned north along the base of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, over the old Trapper’s Trail, to the Arkansas/Platte River divide, and descended along Cherry Creek into the South Platte River.

In Colorado, the original 1849 trail followed the east side of the South Platte River to present-day Greeley, then west via a wagon road to Laporte in Laramier County. The wagon road was built from Laporte north past present-day Virginia Dale Stage Station to the Laramie Plains in southeastern Wyoming.

The trail then proceeded to the northwest around the Medicine Bow Range, crossing the North Platte River before turning north to present-day Rawlins, Wyoming. From there, the trail meandered west before finally joining the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails near modern-day Farson and Fort Bridger, Wyoming.

South Platte River Valley in Colorado, courtesy the Colorado Independent.

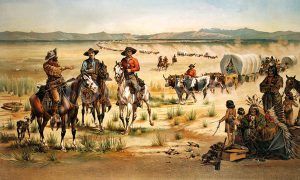

Hearing of the discoveries of gold in California, many Cherokee Indians were enticed to the goldfields to seek their fortunes. According to the Cherokee Advocate’s March 19, 1849, edition, “men worth only a few dollars are worth thousands within a few months of their arrival in California.” The rumors and dreams of gold prompted one Cherokee named Lorenzo Delano to sell his land to travel to California. The sale of his property was listed in the Cherokee Advocate. He was not alone in selling everything he owned on the Cherokee Reservation and heading west.

The route was established in 1849 by a wagon train headed to the California goldfields. Among the expedition members was a group of Cherokee Indians, which is how the trail got its name. The wagon train comprised a group of white settlers from Washington County, Arkansas, and several Indians from the Cherokee Nation. The emigrants left Arkansas on April 24, 1849. Once they arrived in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, and were joined by several Cherokee Indians, they gathered to establish rules and elect a leader. Lewis Evans, a former sheriff of Evansville, Arkansas, was elected Captain, so this expedition is often written as the “Evans/Cherokee” Train. The company called itself the “Washington County Gold Mining Company,” which consisted of 130 people and 40 wagons.

Fort Bridger, Wyoming.

They were the first wagons over explorer John C. Fremont’s Trail in the area and were using his journals. The wagon train followed a trail along the Front Range of Colorado, then turned west along the Colorado/Wyoming Border toward Fort Davy Crocket. They stopped following Fremont’s directions and blazed the Northern Cherokee Trail south of Elk Mountain in Wyoming and across the Red Desert to Fort Bridger.

Not everyone in the Cherokee Nation viewed the gold rush with the same enthusiasm. By the late spring of 1850, many leaders in the Cherokee Tribe became alarmed at the large numbers of men and even women leaving for the goldfields. An article in the Cherokee Advocate on March 19, 1849, described California as a land without law or government. On June 10, 1850, this was followed weeks later by an article in the Cherokee Advocate warning about gold fever. The paper lamented the loss of tribal members taken from their homes by the lure of fame and fortune. The editor wrote: “In this universal rising, his majesty Tul-lo-ni-ca (Cherokee for yellow) has driven numerous Cherokee into the chase, and it is to them to gold for riches at once, and through the journey of life repose in golden dreams.”

Despite the warnings, 1850 marked the beginning of the trail’s continuous use by gold seekers, emigrants, and cattle drovers from Arkansas, Texas, Missouri, and the Cherokee Nation. Travelers who wanted to avoid the cholera epidemic, which ravaged those following the main trails, also continued to use the trail.

Four separate wagon trains of white settlers and Cherokee Indians would make the trek along the Cherokee Trail. In one of those wagon trains was a Cherokee named John Lowery Brown, who kept a diary of their journey. The wagon train left Salina, Oklahoma, on about May 22, 1850. They reached the Santa Fe Trail several days later and turned west along the Arkansas River. Passing the remains of Bent’s Fort in Colorado, the train continued west to Pueblo, where it traveled north along the eastern range of the Rocky Mountains. Near present-day Denver, the group took a more direct route than the Evans party had the previous year, which had continued north along the east bank of the South Platte River.

This group took a more direct route, crossing the Platte River and heading northwest. On June 21, they stopped at the confluence of two unnamed streams to rest. The following day, a train member named Lewis Ralston was gold panning in the stream when he shouted, “Gold!” Ralston was an Irishman whose wife, Elizabeth Kell, had Cherokee ancestry. In early 1850, Ralston and his brother-in-law, Samuel Simons, left Georgia, hoping to make a fortune in the West. When they arrived in northeastern Indian Territory, they joined the Cherokee wagon train for the goldfields.

After Ralston announced his gold find, several other train members quickly joined him, but only a few flakes were found. In the end, they concluded that California gold would be richer.

John Lowery Brown, in his journal, wrote: “June 22 Lay Bye. Found Gold,” and in the margin of the leather-bound book, he noted, “We call this Ralston’s Creek because a man of that name found gold here.”

The emigrant party then proceeded north to Laporte and on to the Laramie Plains, where they turned west along the Colorado-Wyoming border via the Fort Laramie Trail to Fort Bridger. The lead wagon company blazed the road from Tie Siding to Fort Bridger. The changed route then became known as the Southern Cherokee Trail. The wagon train completed its journey, arriving in California on September 28, 1850.

The northern and southern routes of the Cherokee Trail were heavily used, but neither went over Bridger Pass, as it was not open for wagons or used by the military until 1858. At that time, most wagon trains utilized a variation of the Evans 1849 trail, including Bridger Pass.

In addition to gold seekers making their way to California, several military commands also followed the Cherokee Trail. Captain Randolph B. Marcy used it as a return route after he journeyed through Colorado’s mountains from Fort Bridger to Fort Union, New Mexico, in the winter of 1857-58.

Eight years after he had made his trip to the California Goldfields, Lewis Ralston, of the 1850 Cherokee Trail party, returned to “Ralston’s Creek” with Green Russell. Members of this party founded Auraria, which was later absorbed into Denver in 1858 and helped trigger the 1859 Colorado Gold Rush. The confluence of Clear Creek and Ralston Creek, the site of Colorado’s first gold discovery, is now in Arvada, Colorado.

In the 1860s, portions of the trail from northern Colorado to Fort Bridger in Wyoming were incorporated into the Overland Trail and stage route between Kansas and Salt Lake City, Utah. At this time, it was called the Cherokee/Overland Trail.

During the Civil War, the Cherokee Trail was the recommended route between Denver and the Montana goldfields. The Rocky Mountain News advised travelers to take the Cherokee Trail north from Denver and then follow the route west to Fort Bridger. There, they were advised to head north to Fort Hall, Idaho, and then travel the remaining 200 miles to the mines.

The outlaw L.H. Musgrove traveled on the Cherokee Trail from Colorado to Wyoming during the 1860s.

By 1868, the Union Pacific Railroad had laid its track across southern Wyoming. With this railroad completed, the emigrant trails began to lose significance, and freight roads emerged to serve areas south and north of the railroad. By 1868, the only roads remaining in northwestern Colorado had led to Wyoming.

Today, wagon ruts, swales, cut-down ravines, and river banks can be followed from Fort Gibson/Tahlequah, Oklahoma, through Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming to Fort Bridger, Wyoming.

In Colorado, parts of the trail are still visible and walkable in Arapahoe, Douglas, and Larimer Counties. An approximation of the route can be driven on State Highway 83 from Parker near Denver to Colorado Springs.

Other parts of the old trail can be seen on land managed by Wyoming’s Bureau of Land Management. In Sweetwater County, the trail is marked with four-foot-high concrete posts.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2025.

Also See:

The California Trail – Rush to Gold

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

Tales & Trails of the American Frontier

Sources:

Cherokee Trail

Historic Douglas County

Oregon-California Trail Association

Overland Trail

Western Wyoming Community College

Were you looking for The Cherokee Trail of Tears?