“Let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo is exterminated, as it is the only way to bring lasting peace and allow civilization to advance.”

— General Philip Sheridan

Before white settlers began to push into the vast West in large numbers, an estimated 50-60 million buffalo freely roamed the Great Plains. American Indians hunted them for food and other necessities, and a harmonious ebb and flow between man and beast prevailed.

However, after the Civil War, that would change as more and more people moved westward. As a result, new army posts were established, and to supply those many soldiers, the army contracted with local men to supply buffalo meat to feed the troops.

At about the same time, the iron horse began to blaze a trail into the west, and these construction men had to be fed. Adding to the need for food, people back east demanded buffalo robes used as coats and lap robes when riding in sleighs and carriages. These events put many a man to work as buffalo hunters.

Leavenworth, Kansas, became a trading center for the buffalo hides, and tanneries found even more uses for the material, such as making drive belts for industrial machines and grinding buffalo bones into fertilizer. In some places, buffalo tongues became a delicacy in fine restaurants. Soon, the demand for buffalo increased so much that year-round work became available for buffalo hunters.

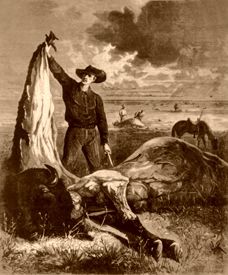

This, all occurring when the economy was depressed after the Civil War, led many a tough man to earn his living as a buffalo hunter. Armed with powerful, long-range rifles, individual hunters could kill as many as 250 buffalo daily. Tanneries paid as much as $3.00 per hide and 25¢ for each tongue, which made a nice living for hundreds of men, including Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Pat Garrett, Wild Bill Hickok, and William F. Cody, to name a few. Unfortunately, once these hides and tongues were taken from the carcasses, the edible buffalo meat was often left to rot on the Plains. By the 1880s, over 5,000 hunters and skinners were involved in the trade.

The Indians watched in dismay as buffalo hunting took on an almost carnival atmosphere when railroads began advertising “hunting by rail.” This occurred when trains sometimes encountered large herds of buffalo crossing the tracks. Seeing a way to capitalize on the problem, the advertising flooded the newspapers, and in no time, sporting men with rifles were shooting buffalo by the hundreds just for fun. Those animals shot from the train were simply left where they died.

Buffalo in South Dakota, photo by Kathy Alexander.

As the slaughter continued, the Indians became increasingly angry and resentful as they watched their primary source of sustenance dwindle at the hands of the white man. This led to more and more Indian attacks, which resulted in U.S. Army retaliation at the height of the Indian Wars. At this time, the U.S. Government desired to separate the Indians from the rest of “civilization” by placing them on reservations. To do this, the U.S. Army aggressively pursued a policy to eradicate the buffalo, intentionally extinguishing the Indians’ sustenance, which would force them onto reservations.

When the Texas Legislature was discussing a bill to protect the buffalo, General Philip Sheridan defended the buffalo hunters and opposed the bill by saying:

”These men have done more in the last two years and will do more in the next year to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well-known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder and lead, if you will, but for lasting peace, let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalos are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.”

By 1884, the great era of the buffalo had ended, and nothing remained of the massive buffalo herds but piles of bones. At that time, only 1,200-2,000 surviving buffalo were left in the United States.

Fortunately, early conservation efforts led to establishing the world’s first national park – Yellowstone, in 1872. There, a small buffalo herd was preserved, but still, what few that were left outside of the park were being killed on Federal land, so, in 1894, the Lacey Act was signed into law, prohibiting the killing of any wildlife in federal preserves. The buffalo were saved from extinction, and today it is estimated that there are over 150,000 bison on public preserves and in private hands.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

”Two years ago, I came upon this road following the buffalo, that my wives and children might have their cheeks plump and their bodies warm. But the soldiers fired on us, and since that time, there has been a noise like that of a thunderstorm, and we have not known which way to go.”

— Comanche Chief Ten Bears

Also See:

Buffalo Hunting With Teddy Roosevelt

See Sources.