Peekskill Bay and the Narrows on the Hudson River by Detroit Photographic Co., 1899.

One of the most significant waterways in American history, the Hudson River stretches approximately 315 miles from its headwaters in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York to its confluence with the Atlantic Ocean at New York City. Eventually, it drains into the Atlantic Ocean at Upper New York Bay. At its southern end, the river is a physical boundary between New Jersey and New York.

Long before English explorer Henry Hudson sailed up the river in 1609 for the Dutch East India Company, the waterway was a major travel route for Native Americans. While it did not provide the Europeans with their desired connection to the Pacific Ocean, the river opened trade routes north to Canada and west to the Great Lakes. Stretching almost straight north, the Hudson is deep, wide, and tidal. The tides, in particular, made it easier for sailboats to navigate the river. The river is named for Henry Hudson.

The Algonquin lived along the river, with three subdivisions of that group: the Lenape, the Wappinger, and the Mahican.

The Lenape inhabiting the lower Hudson River were the people who waited for the explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano onshore, traded with Henry Hudson, and sold the island of Manhattan to the Dutch. Further north, the Wappinger lived from Manhattan Island up to Poughkeepsie, trading with the Lenape to the south and the Mahican to the north. The Mahican lived in the northern valley from present-day Kingston to Lake Champlain, with their capital near present-day Albany.

These three tribes spoke languages that were part of the Algonquin language family, and their relations with each other were mostly peaceful. However, the Mahican were often in direct conflict with the Mohawk Indians to the west, who were part of the Iroquois Confederacy. The Mohawk would sometimes raid Mahican villages from the west.

The Algonquin in the region lived mainly in small clans and villages. One major fortress was called Navish, which was located at Croton Point, overlooking the Hudson River. Other fortresses were located in various locations throughout the Hudson Highlands. Villagers lived in various types of houses, which the Algonquin called Wigwams. The houses could be circular or rectangular. Large families often lived in longhouses that could be 100 feet long. They grew corn, beans, and squash and scavenged for nuts and berries. They also fished, collected oysters, and hunted turkey, deer, rabbits, and other animals.

In 1497, John Cabot, an Italian navigator and explorer, traveled along the coast and claimed the entire country for England. He is credited with the Old World’s discovery of continental North America.

In 1524, Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano visited the bay of New York in the service of Francis I of France. On his voyage, Verrazzano sailed north along the Atlantic seaboard, starting in the Carolinas and ending in New York Harbor, which he thought was the mouth of a major river. However, he never sailed up the Hudson River and left the harbor shortly thereafter.

A year later, Estevan Gomez, a Portuguese explorer sailing for Spain in search of the Northwest Passage, visited New York Bay. The First Nations had a tradition that the Spanish arrived before the Dutch and that the natives obtained maize or Spanish wheat from them.

In 1598, some Dutch employees of the Greenland Company spent the winter in the Bay. Eleven years later, the Dutch East India Company financed English navigator Henry Hudson’s attempt to search for the Northwest Passage, a route believed to be a quicker way to China.

Hudson thought he had found what he was looking for when he entered New York Bay. He and his crew of 18-20 men, sailing on a ship called the Half Moon, traveled about 150 miles up the river near what is now Albany. He docked his ship on the bay’s western shore and claimed the territory as the first Dutch settlement in North America. He proceeded upstream as far as present-day Troy before concluding that no such strait existed there.

Early maps and sailing journals indicate that the area was perceived as inhospitable, characterized by wild animals, poisonous snakes, mountains, and thick forests that were too dense to traverse. The river itself was seen as treacherous, especially in the stretch known as the Hudson Highlands. This area begins about 50 miles north of New York City and extends for about 15 miles between what is now Peekskill and Newburgh. Here, the hills rise more than 1,000 feet along either shore, and fierce currents and strong winds make sailing extremely difficult and dangerous. Areas of the river here were dubbed World’s End and Devil’s Horse Race by the Dutch sailors.

After Henry Hudson realized that the Hudson River was not the Northwest Passage, the Dutch began to examine the region for potential trading opportunities. Dutch explorer and merchant Adriaen Block led a voyage up the lower Hudson River, the East River, and out into Long Island Sound. This voyage determined that the fur trade would be profitable in the region. As such, the Dutch established the colony of New Netherland.

The Dutch settled three major outposts: New Amsterdam, Wiltwyck, and Fort Orange. New Amsterdam was founded at the mouth of the Hudson River and would later become known as New York City. Wiltwyck was founded roughly halfway up the Hudson River between New Amsterdam and Fort Orange. That outpost would later become Kingston. Fort Orange, which later became known as Albany, was the outpost that was the furthest up the Hudson River.

New Netherland and its associated outposts were set up as fur-trading outposts. The Natives began to trap furs and sold them to the Dutch for luxury goods. This trade would eventually deplete the supply of those animals in their territory, thereby decreasing the food supply. The focus on furs also made the Natives economically dependent on the Dutch for trade.

The Dutch West India Company monopolized the region for roughly 20 years before other businessmen were allowed to establish ventures in the colony. New Amsterdam quickly became the colony’s most important city, serving as its capital and a hub for trade and commerce. Initially, the colony was primarily comprised of single adventurers seeking to make a living, but over time, the region transitioned into one where families established households. New economic activities, including food, tobacco, timber, and the slave trade, were eventually incorporated into the colonial economy.

In 1647, Director-General Peter Stuyvesant took over management of the colony. He found it in chaos due to a border war with the English along the Connecticut River and Indian battles throughout the region. Stuyvesant quickly cracked down on smuggling before expanding the outposts along the Hudson River, particularly at Wiltwyck, located at the mouth of the Esopus Creek. He also attempted to establish a fort midway up the Hudson River. However, before that could be done, the British invaded New Netherland via the port of New Amsterdam. Given that New Amsterdam was essentially defenseless, Stuyvesant was forced to surrender the city and the colony to the British. Afterward, New Amsterdam and the colony of New Netherland were renamed New York in honor of the Duke of York. The Dutch briefly regained control of New York, only to relinquish it a few years later, marking the end of Dutch control over the Hudson River.

Under British colonial rule, the Hudson Valley developed into an agricultural hub, with manors established on the east side of the river. Landlords rented land to their tenants at these manors, allowing them to take a share of the crops grown while retaining and selling the rest. Tenants were often kept at a subsistence level so that the landlord could minimize his costs. They also held immense political power in the colony due to driving a large proportion of the agricultural output. Meanwhile, land west of the Hudson River contained smaller landholdings, with many small farmers living off the land. A large crop grown in the region was grain, which was primarily shipped downriver to New York City, the colony’s main seaport, for export back to Great Britain. To export the grain, colonial merchants were given monopolies to grind the grain into flour and export it. Grain production was also at high levels in the Mohawk River Valley.

The Albany Congress took place at Albany City Hall in 1754, and it included officials from the colonies and the Iroquois Confederacy. The subject referred to the tensions between the British and the French, as well as the prelude to the French and Indian War. At the meeting, residents of Albany had the opportunity to interact with people from the other colonies. The result of the Congress was the Albany Plan of Union, which was the first attempt to create a unified government. The plan included seven of the English colonies in North America and consisted of a council with members selected by colonial governments. The British government would select a president-general to oversee the new legislative body. The new colonial body would handle colonial-Indian affairs and resolve territorial disputes between colonies. Although the colonial governments never ratified this plan, it laid the groundwork for later efforts to establish a unified continental government during the American Revolution.

During the American Revolution, the Hudson River was a key waterway. Its connection to the Mohawk River eventually allowed travelers to reach the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. Additionally, the river’s proximity to Lake George and Lake Champlain allowed the British Navy to control the water route from Montreal to New York City. In doing so, the British, under General John Burgoyne, were able to cut off the patriot hub of New England on the eastern side of the Hudson River and focus on rallying the support of loyalists in the South and Mid-Atlantic regions. As a result of the strategy, numerous battles were fought along the river and in nearby waterways.

In 1775, the Americans decided to fortify the area, thereby protecting the river for the transportation of troops and supplies. Critical ferry crossings between Fishkill and Plum Point and Verplanck and Haverstraw connected New England to the Middle Atlantic colonies. Had the British successfully gained control of the river, it would have broken apart the American forces.

The Continental Army later decided to build West Point to prevent another British fleet from similarly sailing up the Hudson River as during the previous battle.

By 1778, the Americans fortified West Point. Fort Montgomery and Fort Clinton had been built near Bear Mountain, and Fort Constitution was located across the river from West Point. That year, the Great Chain was forged of iron links, each two feet long and weighing between 140 and 180 pounds. Anchored to the shore by vast blocks of wood and stone, the chain was attached to logs and floated out into the river, where it ran between West Point and Constitution Island. The idea was to prevent British Ships from sailing up the Hudson from New York City. The Americans had earlier constructed a similar chain further south on the river, from Fort Montgomery to the eastern shore of the Hudson. Still, it was broken by the British soon after. The Great Chain was never tested, as no British ship got that far up the river after its creation.

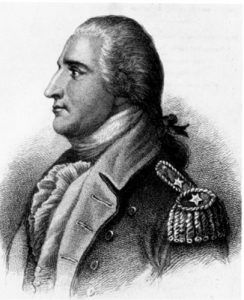

During Benedict Arnold’s control over West Point, he weakened its defenses, including neglecting repairs on the West Point Chain. Arnold was secretly loyal to the British at the time and planned to hand over West Point’s plans to British Major John Andre. On September 21, 1780, Andre sailed up the river on the Vulture to meet Arnold. The following day, an outpost at Verplanck’s Point fired on the ship, which sailed back downriver. Andre was forced to return to New York City by land; however, he was captured near Tarrytown on September 23 by three Westchester militiamen and was later hanged. Arnold later fled to New York City aboard Vulture.

George Washington moved his headquarters to Newburgh in 1782, where he remained through the end of the Revolutionary War, setting up shop in the home of Jonathan Hasbrouck. The house is now a state historic site, featuring period furnishings, firearms, documents, and military artifacts from the Revolutionary War, as well as portraits of George and Martha Washington, and an exhibit depicting the Americans’ defense of the Highlands against the British.

From the beginning, thousands of visitors plied its waters on their travels. The river’s dramatic scenery – the Palisades, the Hudson Highlands, the Catskills – soon became renowned worldwide. The Hudson and its scenery became a popular subject for artists and writers, inspired by its beauty and facilitated by its proximity to the port of New York.

At the beginning of the 19th century, transportation from the U.S. East Coast was difficult. Boat travel was still the fastest mode of transportation at the time. To facilitate boat travel throughout the interior of the United States, numerous canals were constructed between internal bodies of water in the country. These canals transferred freight throughout the inland U.S..

As publishing developed at that time, with the inclusion of pictures and travel accounts, an increasing number of travelers from all parts of the Western world were drawn to the region.

After seeing the effects of a lack of adequately trained officers on his troops, Washington pleaded with the newly formed government to form a military academy. However, it wasn’t until after his death that the United States Military Academy at West Point was established in 1802 under President Thomas Jefferson.

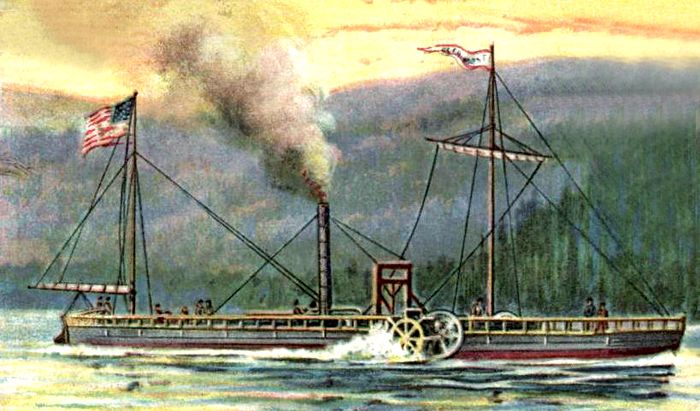

Life on the river was transformed when inventor Robert Fulton developed the world’s first commercially successful steamboat in 1807. The North River Steamboat (later known as Clermont) became the first commercially successful steamboat carrying passengers between New York City and Albany along the Hudson River. Offering a fast and affordable way to travel, steamboats’ ability to carry passengers and freight on schedule revolutionized water travel, ushering in a new age of technological advancements in transportation.

Beginning in 1820, the Erie Canal connected the Hudson to the Great Lakes, and soon after, the Delaware & Hudson Canal linked the river to Pennsylvania coal fields, supplying the raw materials and fuel that transformed New York City into the great American metropolis. The Hudson’s importance as one of the nation’s main arteries of trade continued to grow.

During the Industrial Revolution, the Hudson River became a central hub for industrial production, particularly around Albany and Troy. The river facilitated the rapid and easy transportation of goods from the interior of the Northeast to the coast. Hundreds of factories were built around the Hudson River, including Poughkeepsie, Newburgh, Kingston, and Hudson.

The first railroad in New York, the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, opened in 1831 between Albany and Schenectady on the Mohawk River. It enabled passengers to bypass the slowest part of the Erie Canal.

The Hudson Valley proved attractive for railroads once technology progressed to the point where it was feasible to construct the required bridges over tributaries. The Troy and Greenbush Railroad was chartered in 1845 and opened that same year, running a short distance on the east side between Troy and Greenbush, now known as East Greenbush (east of Albany).

By 1850, approximately 150 steamboats were navigating the river, carrying as many as a million passengers. By that time, water transportation and travel reached their peak, as railroads began to compete for freight and passengers. While trains never completely replaced riverboats, they represented a significant improvement in transportation engineering and ease of travel. For the first time in the Hudson River’s history, land travel surpassed water travel, and both freight traffic and tourism experienced significant increases. Fortunately for tourists, the Hudson River Railroad hugged the shoreline and was nearly as scenic as the boats.

As tuberculosis and other dangerous diseases began to spread in New York City in the mid-1800s, the Hudson Valley took on another personality — a health retreat. Until the early 1900s, city folk flocked to the Valley to experience the therapeutic powers they believed it held. The mountains, fresh air, and evergreen forests were believed to offer the perfect conditions for good health, and they were located in close proximity to the city. In the early 1900s, however, the Adirondacks and areas further away became more desirable.

At about the same time, wealthy New York businessmen began to buy property in the Hudson Valley for summer and weekend retreats. The railroad even made commuting into the city a realistic possibility. Politicians, bankers, railroad magnates, and other well-known professionals began to build grand estates here. Financier J. Pierpont Morgan, New York Governor and U.S. Senator Hamilton Fish, National City Bank president James Stillman, architect Richard Upjohn, and Union Pacific railroad president Edward H. Harriman were just a few of the area’s new inhabitants.

An area in the middle Hudson region, often called “Millionaires Row,” contains several homes open to the public that should be part of anyone’s visit to the Hudson Valley. The Vanderbilt Mansion Historic Site in Hyde Park was built in the late 1800s in a Beaux-Arts style with an interior designed by turn-of-the-century decorators. The mansion features furnishings, tapestries, rugs, and porcelains from this period, as well as a coach house, formal garden, and, of course, a magnificent view of the river.

The Hudson River Railroad was chartered in 1851 as a continuation of the Troy and Greenbush south to New York City and was completed in 1851. In 1866, the Hudson River Bridge opened over the river between Greenbush and Albany, allowing through traffic between the Hudson River Railroad and the New York Central Railroad, extending west to Buffalo.

In 1853, the New York Central Railroad consolidated many smaller lines to funnel freight and passengers into the city from a rail network that soon stretched across the continent.

The New York, West Shore, and Buffalo Railway began at Weehawken Terminal and ran up the west shore of the Hudson as a competitor to the merged New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. Construction was slow, but the line was finally completed in 1884; the New York Central purchased the line the following year.

In 1892, the Hudson River was declared a federal government waterway.

When the Poughkeepsie Bridge opened in 1889, it became the longest single-span bridge in the world.

On September 14, 1901, then-U.S. Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was at Lake Tear of the Clouds after returning from a hike to the Mount Marcy summit when he received a message informing him that President William McKinley, who had been shot two weeks earlier but was expected to survive, had taken a turn for the worse. Roosevelt hiked down the mountain to the closest stage station at Long Lake, New York. He then took a 40-mile midnight stagecoach ride through the Adirondacks to the Adirondack Railway station at North Creek, where he discovered that McKinley had died. Roosevelt took the train to Buffalo, New York, where he was officially sworn in as president. The 40-mile route is now designated the Roosevelt-Marcy Trail.

In 1910, pilot Glenn Curtiss broke the American flight distance record. He flew his plane for five hours from a field near Albany to Governor’s Island just south of Manhattan, flying over the Hudson River for most of his flight. The flight was 152 miles long, and he made one planned stop in Poughkeepsie, which was roughly the midpoint of the flight. He also made an unplanned stop just south of Spuyten Duyvil in Uptown Manhattan because he was low on fuel. A train full of reporters followed his plane the entire way, and the mayor of Albany gave Curtiss a letter to give to the mayor of New York City. Importantly, Curtiss’ flight demonstrated that aircraft could eventually be used for transportation between two major cities.

From 1946 to 1971, the Hudson River Reserve Fleet was located on the Hudson River.

In 2004, Christopher Swain became the first person to swim the entire length of the Hudson River. The swim took 36 days, along the 315 miles of the Hudson from the Adirondacks to New York City. Swain participated in the swim to raise awareness about making the river safe for drinking and swimming. He braved a combination of rapids, dams, snapping turtles, and pollution to complete his journey. The marathon swim was a significant component of “Swim for the River,” a documentary that chronicles the history of pollution in the Hudson River and the efforts to combat it.

On January 15, 2009, U.S. Airways Flight 1549 made an emergency ditching onto the Hudson River beside Manhattan. The flight was a domestic, commercial passenger flight with 150 passengers and five crew members traveling from LaGuardia Airport in New York City to Charlotte Douglas International Airport in Charlotte, North Carolina. After striking a flock of Canada geese during its initial climb out, the airplane lost engine power and ditched on the Hudson River off Midtown Manhattan with no loss of human life. All 155 occupants safely evacuated the airliner and were rescued by nearby ferries and other watercraft. The airplane was still virtually intact, though partially submerged and slowly sinking. The entire crew of Flight 1549 was later awarded the Master’s Medal of the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators. NTSB board member Kitty Higgins described it as “the most successful ditching in aviation history”.

On October 3, 2009, the Poughkeepsie-Highland Railroad Bridge reopened as the Walkway over the Hudson. This pedestrian walkway over the Hudson River opened as part of the Hudson River Quadricentennial Celebrations and connects over 25 miles of existing pedestrian trails.

Today, tourists come from all parts of the United States and Europe to see the Hudson Valley. It is an essential leg on trips to Saratoga Springs, the Adirondacks, Niagara Falls, and Canada. West Point and other Revolutionary War sites are popular with visitors. For most travelers, the region’s natural scenery and its splendid river houses are the principal attractions.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, July 2025.

Also See:

Sources:

Encyclopedia Britannica

Hudson River

Hudson River Historical Overview

Hudson River Maritime Museum

Wikipedia – Hudson River

Wikipedia – Hudson River History