By Henry Howe in 1857

Juan Ponce de Leon.

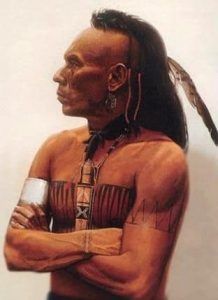

Twenty years after Juan Ponce de Leon, ex-governor of Puerto Rico, discovered the great event that immortalized the name of Christopher Columbus, Florida. Sailing from that island in March 1513, he discovered an unknown country, which he named Florida, from the abundance of its flowers, the trees being covered with blossoms, and its first being seen on Easter Sunday, a day called by the Spaniards, Pascua Florida. Other explorers soon visited the same coast. In May 1539, Hernando De Soto, the Governor of Cuba, landed at Tampa Bay with 600 followers. He marched into the interior; on May 1, 1541, he discovered the Mississippi River, the first European to behold that mighty river.

For many years, Spain claimed the whole country- bounded by the Atlantic to the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River on the north, all of which bore the name of Florida. About twenty years after discovering the Mississippi River, some Catholic missionaries attempted to form settlements at St. Augustine and its vicinity. A few years later, a colony of French Calvinists had been established on the St. Marys River near the coast. In 1565, this settlement was annihilated by an expedition from Spain under Pedro Menendez de Aviles, and about 900 French men, women, and children were cruelly massacred. The bodies of many of the slain were hung from trees, with the inscription, “Not as Frenchmen, but as heretics.”

Having accomplished his bloody errand, Menendez founded St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest town by half a century of any now in the Union. Four years after, Dominique de Gourgues, burning to avenge his countrymen, fitted out an expedition at his own expense and surprised the Spanish colonists on the St. MarysRiver, destroying the ports, burning the houses, and ravaging the settlements with fire and sword, finishing the work by also suspending some of the corpses of his enemies from trees, with the inscription “Not as Spaniards, but, as murderers.” Unable to hold possession of the country, De Gourgues retired to his fleet. Florida, excepting for a few years, remained under the Spanish crown, suffering much in its early history from the vicissitudes of war and piratical incursions, until 1819, when, vastly diminished from its original boundaries, it was ceded to the United States, and in 1845 became a state.

In 1535, James Cartier, a distinguished French mariner, sailed with an exploring expedition up the St. Lawrence River and took possession of the country in the name of his king, called it “New France.” In 1608, the energetic Samuel de Champlain created a nucleus for the settlement of Canada, founding Quebec. This was the same year with the settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, and 12 years before that, the Puritans first stepped upon the rocks of Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Until late in the century, owing to the hostility of the Indians bordering Lakes Ontario and Erie, the adventurous missionaries, on their route west, on pain of death, were compelled to pass far to the north through “a region horrible with forests,” by the Ottawa and French Rivers of Canada.

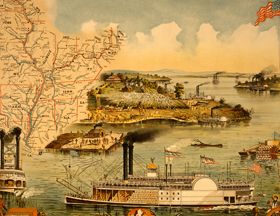

As yet, no Frenchman had advanced beyond the Fox River of Winnebago Lake in Wisconsin, but, in May 1673, the missionary Jacques Marquette, with a few companions, left Mackinac in canoes, passed up Green Bay, entered the Fox River, crossed the country to the Wisconsin River, and, following its current, passed into and discovered the Mississippi River; down which, they sailed several hundred miles, and returned in the Autumn. The discovery of this great river gave great joy in New France, it being “a pet idea” of that age that some of its western tributaries would afford a direct route to the South Sea and China. Monsieur Robert de La Salle, a man of indefatigable enterprise, having been engaged in preparation for several years, in 1682 explored the Mississippi River to the sea and took formal possession of the country in the name of the King of France in honor of whom he called it Louisiana. In 1685, he also took formal possession of Texas and founded a colony on the Colorado River, but La Salle was assassinated, and the colony dispersed.

The descriptions of the beauty and magnificence of the Valley of the Mississippi River, given by these explorers, led many adventurers from the cold climate of Canada to follow the same route and commence settlements. In about 1680, Kaskaskia and Cahokia in Illinois, the oldest towns in the Mississippi Valley, were founded. Kaskaskia became the capital of Illinois country, and in 1721, a Jesuit college and monastery were founded there.

Peace with the Iroquois, Huron, and Ottawa tribes in 1700 allowed the French to settle in western Canada. In June 1701, De la Motte Cadillac, with a Jesuit missionary and a hundred men, laid the foundation of Detroit. The French now claimed all of the vast regions south of the lakes under Canada or New France. This excited the jealousy of the English, and the New York legislature passed a law for hanging every Popish priest who should come voluntarily into the province.

The French, chiefly through the mild and conciliating course of their missionaries, had gained so much influence over the western Indians that, when war broke out with England in 1711, the most powerful of the tribes became their allies, and the latter unsuccessfully attempted to restrict their claims to the country south of the lakes. The Fox Nation, allies of the English, in 1713 attacked Detroit but were defeated by the French and their Indian allies. The Treaty of Utrecht, this year, ended the war.

By 1720, a profitable trade had arisen in furs and agricultural products — between the French of Louisiana and those of Illinois, and settlements had been made on the Mississippi River, below the junction of the Illinois River. To confine the English to the Atlantic coast, the French adopted the plan of forming a line of military posts to extend from the great northern lakes to the Mexican Gulf, and as one of the links of the chain, Fort Chartres was built on the Mississippi River, near Kaskaskia; and in its vicinity soon flourished the villages of Cahokia, and Prairie du Rocher.

At this time, the Ohio River was little known to the French and was a little stream on their early maps. Early in the 1700s, their missionaries had penetrated the sources of the Alleghany River. In 1721, Chabert de Joncaire, a French agent and trader, established himself among the Seneca at Lewistown, and Fort Niagara was erected near the falls five years subsequent. In 1735, according to some authorities, Post St. Vincent was erected on the Wabash River. Almost coeval with this was the military post of Presque Isle, on the site of Erie, Pennsylvania; from there, a cordon of posts extended on the Alleghany River to Pittsburgh and, from there, down the Ohio River to the Wabash River.

The Janis-Ziegler House, or Green Tree Tavern, in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, was probably built in the 1790s. The house combines French and American architectural styles. By Kathy Alexander.

In 1749, the French regularly explored the Ohio River and formed alliances with the Indians in western New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. The English, who claimed the whole west to the Pacific but whose settlements were confined to the comparatively narrow strip east of the mountains, were jealous of the rapidly increasing power of the French in the west. Not content with exciting the Indians to hostilities against them, they stimulated private enterprise by granting 600,000 acres of choice land on the Ohio River to the “Ohio Company.”

By 1751, there were in the Illinois country the settlements of Cahokia, five miles from St. Louis; St. Philip’s, 45 miles farther down the river; Ste. Genevieve, a little lower still and on the east side of the Mississippi River, Fort Chartres, Kaskaskia, and Prairie du Rocher. The largest of these was Kaskaskia, which contained nearly 3,000 souls at one time.

To strengthen the French dominion’s establishment, Samuel de Champlain’s genius saw that it was essential to establish missions among the Indians. Up to this period, “the far west” had been untrod by the foot of the white man. In 1616, a French Franciscan named Joseph Le Caron passed through the Iroquois and Wyandot nations — to streams running into Lake Huron, and in 1634, two Jesuits founded the first mission in that region. But, just a century had elapsed from the discovery of the Mississippi River, where the first Canadian envoys met the Indian nations of the northwest at the falls of St. Mary’s, below the outlet of Lake Superior.

It was not until 1659 that any adventurous fur traders wintered on the shores of this vast lake, nor until 1660 that Rene Mesnard founded the first missionary station upon its rocky and inhospitable coast. Perishing soon after in the forest, it was left to Father Claude Allouez, five years subsequent, to build the first permanent habitation of white men among the northwestern Indians. In 1668, the mission was founded at the falls of St. Mary River by Claude Dablon and Jacques Marquette; in 1670, Nicholas Perrot, agent for the intendant of Canada, explored Lake Michigan near its southern termination. The French took formal possession of the northwest in 1671, and Marquette established a missionary station at Point St. Ignace, on the mainland north of Mackinac, the first settlement in Michigan.

In 1748, the Ohio Company, composed mainly of wealthy Virginians, dispatched Christopher Gist to explore the country, gain the goodwill of the Indians, and ascertain the plans of the French. Crossing overland to the Ohio River, he proceeded down it to the Great Miami River, up which he passed to the towns of the Miami tribes, about 50 miles north of the site of Dayton, Ohio. The following year the company established a trading post in that vicinity, on Loraroies Creek, the first point of English settlement in the western country. It was soon after broken up by the French.

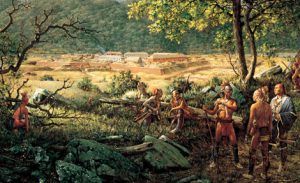

In 1753, Robert Dinwiddie, governor of Virginia, sent George Washington, then 21 years of age, as commissioner to remonstrate with the French commandant at Fort le Boeuf, near the site of Erie, Pennsylvania, against encroachments of the French. The English claimed the country by her first royal charters, and the French by the more substantial title of discovery and possession. The result of the mission proving unsatisfactory was that the English. However, it was a time of peace, raising a force to expel the invaders from the Ohio River and its tributaries. A detachment under Lieutenant Ward erected a fort on the site of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. However, it was surrendered shortly after, in April 1754, to a superior force of French and Indians under Claude-Pierre Pecaudy de Contrecœur. Its garrison was peaceably permitted to retire to the frontier post of Cumberland. Contrecoeur then erected a strong fortification at “the fork” under the name of Fort Duquesne.

Both nations now took measures for the struggle that was to ensue. On May 28, 1755, a strong detachment of Virginia troops under George Washington surprised a small body of French from Fort Duquesne, killed its commander Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville and ten men, and took nearly all the rest prisoners. He then fell back and erected Fort Necessity near Uniontown, Pennsylvania.

In July, he was attacked by a large body of French and Indians, commanded by Louis Coulon de Villiers, and after a gallant resistance, compelled to capitulate, with permission to retire unmolested and under the express stipulation that farther settlements or forts, should not be founded by the English, west of the mountains, for one year.

On July 9, 1755, General Edward Braddock was defeated within ten miles of Fort Duquesne. His army, composed mainly of veteran English troops, passed into an ambuscade formed by a far inferior body of French and Indians, who, lying concealed in two deep ravines, each side of his line of march, poured in upon the compact body of their enemy, volleys of musketry, with almost perfect safety to themselves. The Virginia provincials, under George Washington, by their knowledge of border warfare and remarkable bravery, alone saved the army from complete ruin. General Braddock was mortally wounded by a provincial named Fausett. A brother of the latter had disobeyed the silly orders of the General that the troops should not take positions behind the trees when Braddock rode up and struck him down. Fausett, who saw the whole transaction, immediately drew up his rifle and shot him through the lungs, partly from revenge and partly as a measure of salvation to the army, which was sacrificed to his headstrong stubbornness and inexperience. This battle gave the French and Indians a complete ascendancy on the Ohio River and put a check on the operations of the English west of the mountains for two or three years. In July 1758, General John Forbes, with 7,000 men, left Carlisle, Pennsylvania, for the west. A corps in advance, principally of Highland Scotch, under Major James Grant, was defeated on September 13 in the vicinity of Fort Duquesne on the site of Pittsburgh. A short time after, the French and Indians made an unsuccessful attack upon the advanced guard under Colonel Henry Boquet.

In November, the commandant of Fort Duquesne, unable to cope with the superior force approaching under General John Forbes, abandoned the fortress and descended to New Orleans. He erected Fort Massac on his route in honor of Marquis de Massiac, who superintended its construction. It was upon the Ohio River, within 40 miles of its mouth — and the limits of Illinois. Forbes repaired Fort Duquesne and changed its name to Fort Pitt in honor of the English Prime Minister.

The English were now, for the first time, in possession of the upper Ohio River. In the spring, they established several posts in that region, prominent among which was Fort Burd, or Redstone Old Fort, on the site of Brownsville.

Owing to the treachery of South Carolina Governor Lyttleton in 1760, by which 22 Cherokee chiefs on an embassy of peace were made prisoners at Fort George on the Savannah River, that nation flew to arms and for a while desolated the frontiers of Virginia and the Carolinas. Fort Loudoun, in East Tennessee, having been besieged by the Indians, the garrison capitulated on August 7, and the day afterward, while on the route to Fort George, was attacked, and the more significant part massacred. In the summer of 1761, Colonel James Grant invaded their country and compelled them to sue for peace. The British arms achieved the most brilliant success in the north. Ticonderoga, Crown Point, Fort Niagara, and Quebec were taken in 1759; the next year, Montreal fell, and with it, all of Canada.

By the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France gave up her claim to New France and Canada, embracing all the country east of the Mississippi River, from its source to the Bayou Iberville. The remainder of her Mississippi possessions, embracing Louisiana west of the Mississippi River and the Island of Orleans, she secretly ceded to Spain, which terminated the dominion of France on this continent and her vast plans for empire.

At this period, Lower Louisiana had become of considerable importance. The explorations of Robert de La Salle in the Lower Mississippi country were renewed in 1697 by Lemoine D’ Iberville, a brave French naval officer. Sailing with two vessels, he entered the Mississippi River in March 1698 by the Bayou Iberville. He built forts on the Bay of Biloxi, Mississippi, and at Mobile, Alabama, deserted for the Island of Dauphine, the colony’s headquarters for years. He also erected Fort Balise at the mouth of the river and fixed it on the site of Fort Rosalie, which later became the scene of a bloody Indian war.

After he died in 1706, Louisiana was little more than a wilderness, and a vain search for gold and trading in furs, rather than the substantial pursuits of agriculture, allured the colonists. Much time was lost in discovery journeys and collecting furs among distant tribes. Biloxi was barren land of the occupied lands, and the Isle of Dauiihine soil was poor. Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the brother and successor of D’ Iberville, was at the fort on the Delta of the Mississippi River, where he and his soldiers were liable to inundations and held joint possession with mosquitoes, frogs, snakes, and alligators.

In 1712, Antoine de Crozat, an East India merchant of vast wealth, purchased a grant of the entire country with the exclusive right of commerce for 16 years. But, in 1717, the speculation having resulted in his ruin, all to the injury of the colonists, he surrendered his privileges. Soon after, several other adventurers, under the name of the Mississippi Company, obtained from the French government a charter, which gave them all the rights of sovereignty, except the bare title, including a monopoly of the trade and the mines. Their expectations were chiefly from the mines and on the strength of a former traveler, Nicolas Perrot, having discovered a copper mine in the valley of St. Peters, the directors of the company assigned to the soil of Louisiana, silver, and gold, and the mud of the Mississippi River, diamonds and pearls. The notorious Law, who then resided in Paris, was the secret agent of the company. To form its capital, its shares were sold at five hundred lives each, and such was the speculating mania of the times that, in a short time, more than a hundred million was realized. Although this proved ruinous to individuals, the colony greatly benefited from the consequent emigration, and agriculture and commerce flourished.

In 1719, Renault, an agent of the Mississippi Company, left France with about 200 miners and emigrants to carry out the company’s mining schemes. He bought 500 slaves at St. Domingo to work the mines, which he conveyed to Illinois in 1720. He established himself a few miles above Kaskaskia, Illinois, and founded the village of St. Philips. Extravagant expectations existed in France of his probable success in obtaining gold and silver. He sent out exploring parties in various sections of Illinois and Missouri. His explorations extended to the banks of the Ohio and Kentucky Rivers and even to the Cumberland Valley in Tennessee, where at “French Lick,” the French established a trading post on the site of Nashville. Although Renault was woefully disappointed in not discovering extensive mines of gold or silver, he made various discoveries of lead, the mines north of Potosi and those on the St. Francis River. He eventually turned his attention to the smelting of lead, which he made considerable quantities of and shipped to France. He remained in the country until 1744. Nothing of consequence was again done in mining until after the American Revolution.

In 1718, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville laid out the town of New Orleans on the plan of Rochefort, France. Some four years after, the bankruptcy of Law threw the colony into the most significant confusion and occasioned widespread ruin in France, where speculation had been carried to an extreme unknown before.

The expenditures for Louisiana were consequently stopped, but the colony had now gained the strength to struggle for herself. Louisiana was divided into nine cantons, of which Arkansas and Illinois each formed one.

At about this time, the colony had considerable difficulty with the Indian tribes and was involved in wars with the Chickasaw and the Natchez. This latter-named tribe was finally wholly conquered. Their remnant dispersed among other Indians so that once powerful people, as a distinct race, were entirely lost. Their name alone survives as that of a flourishing city. Tradition-related singular stories of the Natchez. It was believed that they emigrated from Mexico and were kindred to the Incas of Peru. The Natchez alone, of all the Indian tribes, had a consecrated temple where appointed guardians maintained a perpetual fire. Near the temple, on an artificial mound, stood the dwelling of their chief — called the Great Sun; who was supposed to be descended from that luminary, and all abound were grouped the tribe’s dwellings. His power was absolute; the dignity was hereditary and transmitted exclusively through the female line, and the race of nobles was so distinct that usage had molded language into the forms of reverence.

In 1732, the Mississippi Company relinquished its charter to the king after holding possession for 14 years. At this period, Louisiana had about 5,000 whites and 2,500 blacks. Agriculture was improving in all the nine cantons, particularly in Illinois, which was considered the granary of the colony. Louisiana continued to advance until the war broke out with England in 1755, which resulted in the overthrow of French dominion.

Immediately after the peace of 1763, all the old French forts in the west, as far as Green Bay were repaired and garrisoned with British troops. Agents and surveyors, too, were examining the finest lands east and northeast of the Ohio River. Judging from the past, the Indians were satisfied that the British intended to possess the whole country. That year, the celebrated Ottawa chief, Pontiac, burning with hatred against the English, formed a general league with the western tribes. By the middle of May, all the western posts had fallen — or were closely besieged by the Indians, and the whole frontier, for almost a thousand miles, suffered from the relentless fury of savage warfare. Treaties of peace were made with the different tribes of Indians in the year following, at Niagara by Sir William Johnson; at Detroit and vicinity by General John Bradstreet, and, in what is now Coshocton County, Ohio, by Colonel Henry Boquet; at the German Flats, on the Mohawk, with the Six Nations and their confederates. By these treaties, extensive tracts were ceded by the Indians in New York and Pennsylvania and south of Lake Erie.

Peace having been concluded, the excitable frontier population began to cross the mountains. Small settlements were formed on the main routes, extending north toward Fort Pitt and south to the headwaters of the Holston and Clinch Rivers in the vicinity of southwestern Virginia. In 1766, a town was laid out near Fort Pitt. Military land warrants had been issued in great numbers, and a perfect mania for western land had taken possession of the people of the middle colonies. The treaty made by Sir William Johnson at Fort Stanwix, on the site of Utica, New York, in October 1768, with the Six Nations and their confederates, and those of Hard Labor and Lochaber, made with the Cherokee, afforded a pretext under which the settlements were advanced. It was now falsely claimed that the Indian title was extinguished east and south of the Ohio River indefinitely, and the spirit of emigration and speculation in the land significantly increased. Among the land companies formed at this time was the “Mississippi Company,” of which George Washington was an active member.

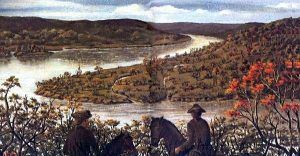

Until this period, very little was known by the English of the country south of the Ohio River. In 1754, James M. Bride, along with some others, passed down the Ohio River in canoes, landed at the mouth of the Kentucky River, and marked the initials of their names and the date on the barks of trees. On their return, they were the first to give a particular account of the beauty and richness of the country to the inhabitants of the British settlements. No further notice seems to have been taken of Kentucky until 1767, when John Finlay, an Indian trader, with others, passed through a part of the rich lands of Kentucky — then called by the Indians “the Dark and Bloody Ground.” Finlay, returning to North Carolina, fired the curiosity of his neighbors with the reports of the discoveries he had made. In consequence of this information, Colonel Daniel Boone, in company with Finlay, Stewart, Holden, Monay, and Cool, set out from their residence on the Yadkin River in North Carolina on May 1, 1769.

After a long and fatiguing march over a mountainous and pathless wilderness, they arrived on the Red River. Here, from the top of an eminence, Boone and his companions first beheld a distant view of the beautiful lands of Kentucky. The plains and forests abounded with wild beasts of every kind; deer and elk were common; the buffalo were seen in herds, and the plains were covered with the richest verdure. The glowing descriptions of these adventurers inflamed the imaginations of the borderers and their sterile hills and mountains beyond lost their charms compared to the fertile plains of this newly-discovered Paradise in the West.

In 1770, Ebenezer Silas and Jonathan Zane settled in Wheeling, West Virginia. In 1771, such was the rush of emigration to western Pennsylvania and western Virginia, in the region of the Upper Ohio River, that every kind of breadstuff became so scarce that for several months, a significant part of the population was obliged to subsist entirely on meats, roots, vegetables, and milk, to the entire exclusion of all breadstuffs. Hence, that period was long after, known as “the starving year.” Settlers, enticed by the beauty of the Cherokee country, emigrated to East Tennessee, and hundreds of families also moved farther south to the mild climate of West Florida, which at this period extended to the Mississippi River. In the summer of 1773, Frankfort and Louisville, Kentucky, were laid out. The following year was signalized by “Dunmore’s War,” which temporarily checked the settlements.

In the summer of 1774, several other parties of surveyors and hunters entered Kentucky, and James Harrod erected a dwelling on or near the site of Harrodsburg, around which afterward arose “Harrod Station.” In the year 1775, Colonel Richard Henderson, a native of North Carolina, on behalf of himself and his associates, purchased from the Cherokee all the country lying between the Cumberland River and Cumberland Mountains and Kentucky River, and south of the Ohio River, which now comprises more than half of the State of Kentucky. The new country he named Transylvania. The first legislature sat at Boonsborough and formed an independent government on liberal and rational principles. Henderson was very active in granting lands to new settlers. The legislature of Virginia subsequently crushed his schemes, claiming the sole right to purchase lands from the Indians, and declared his purchase null and void. But, as compensation for the services rendered in opening the wilderness, the legislature granted the proprietors a tract of land, twelve miles square, on the Ohio River, below the mouth of Green River.

In 1775, Daniel Boone, in Henderson’s employment, laid out the town and fort afterward called Boonsborough. From this time, Boonsborough and Harrodsburg became the nucleus and support of emigration and settlement in Kentucky. In May, another fort was built under the command of Colonel Benjamin Logan, named Logan’s Fort. It stood on the site of Stanford in Lincoln County and became an important post.

In 1776, the jurisdiction of Virginia was formally extended over the colony of Transylvania, which was organized into a county named Kentucky. The first court was held at Harrodsburg in the spring of 1787. At this time, the American Revolution was in total progress, and the early settlers of Kentucky were particularly exposed to the incursions of the Indian allies of Great Britain. The early French settlements in Illinois country, now having that power, formed important points around which the British assembled the Indians and instigated them to murderous incursions against the pioneer population.

The year 1779 was marked in Kentucky by the passage of the Virginia Land Laws. At this time, claims of various kinds existed on the western lands. Commissioners were appointed to examine and judge these various claims as they might be presented. These having been provided for, the residue of the rich lands of Kentucky was in the market. Due to the passage of these laws, many emigrants crossed the mountains into Kentucky to locate land warrants. In the years 1779-80 and 1781, the great and absorbing topic in Kentucky was to enter a survey and obtain patents for the richest lands, and this, too, in the face of all the horrors and dangers of an Indian war.

Although the main features of the Virginia land laws were just and liberal, a significant defect existed in their not providing for a general survey of the country by the parent state and its subdivision into sections and parts of lections. Each warrant-holder was required to do his survey and had the privilege of locating according to his pleasure; interminable confusion arose from want of precision in the boundaries. In unskillful hands, entries, surveys, and patents were piled upon each other, overlapping and crossing in inextricable confusion; hence, when the country became densely populated, vexatious lawsuits and perplexities arose. Such men as Simon Kenton and Daniel Boone, who had done so much for the welfare of Kentucky in its early days of trial, found their indefinite entries declared null and void and were dispossessed, in their old age, of any claim upon that soil for which they had periled their all.

For a time only, the close of the American Revolution suspended Indian hostilities, and the Indian war was again carried on with renewed energy. This arose from the failure of both countries to execute the treaty’s terms fully. By it, England was obligated to surrender the northwestern posts within the Union’s boundaries and return slaves taken during the war. The United States, on its part, had agreed to offer no legal obstacles to the collection of debts due from her citizens to those of Great Britain. Virginia, indignant at the removal of her slaves by the British fleet, by law, prohibited the collection of British debts. At the same time, England, in consequence, refused to deliver the posts, so she held them for more than ten years until Jay’s Treaty was concluded.

Settlements rapidly advanced. Simon Kenton having, in 1784, erected a block-house on the site of Maysville, — then called Limestone — that became the point from whence the stream of emigration, from down its way on the Ohio River, turned into the interior.

In the spring of 1783, the first court in Kentucky was held at Harrodsburg. At this period, establishing a government independent of Virginia appeared paramount due to troubles with the Indians. For this object, the first convention in Kentucky was held at Danville in December 1784, but it was not consummated until eight different conventions had been held, running through a term of six years. The last was assembled in July 1790; on February 4, 1791, Congress passed the act admitting Kentucky into the Union, and in April, she adopted a State Constitution.

Before this, unfavorable impressions prevailed in Kentucky against the Union, in consequence of the inability of Congress to compel a surrender of the northwest posts and the apparent disposition of the northern States to yield to Spain, for twenty years, the sole right to navigate the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, the exclusive right to which was claimed by that power, it being within her dominions. Kentucky was suffering under the horrors of Indian warfare and having no government of her own; she saw that beyond the mountains, she could not afford them protection. When, in the year 1786, several States in Congress showed a disposition to yield the right of navigating the Mississippi River to Spain for certain commercial advantages, which would inure to their benefit, but, not in the least to that of Kentucky, there arose a universal voice of dissatisfaction. Many favored declaring the independence of Kentucky and erecting an independent government west of the mountains.

Spain was then an immense land-holder in the west. She claimed it was all east of the Mississippi River, lying south of the 31st degree of north latitude, and all west of that river to the ocean.

In May 1787, a convention was assembled at Danville to remonstrate with Congress against ceding the Mississippi River’s navigation to Spain. Still, it having been ascertained that Congress, through the influence of Virginia and the other southern States, would not permit this, the convention had no occasion to act upon the subject.

In 1787, quite a sensation arose in Kentucky because General James Wilkinson opened a profitable trade with New Orleans, who descended thither in June with a boatload of tobacco and other Kentucky productions. Previously, all those who ventured down the river within the Spanish settlements had their property seized. The Spanish Minister held out the lure that if Kentucky would declare her independence from the United States, the navigation of the Mississippi River should be opened to her, but this privilege would never be extended. At the same time, she was a part of the Union due to existing commercial treaties between Spain and other European powers.

In the winter of 1788-99, the notorious Dr. John Connolly, a secret British agent from Canada, arrived in Kentucky. His object appeared to be to sound the temper of her people and ascertain if they were willing to unite with British troops from Canada and seize upon and hold New Orleans and the Spanish settlements on the Mississippi River. He dwelt upon the advantages it must be to the people of the West to hold and possess the right to navigate the Mississippi River, but his overtures were not accepted.

At this time, settlements had been commenced within the present limits of Ohio. Before giving a sketch of these, we glance at the western land claims.

The claim of the English monarch to the Northwestern Territory was ceded to the United States by the treaty of peace, signed in Paris on September 3, 1783. During the pendency of this negotiation, Mr. Oswald, the British commissioner, proposed the Ohio River as the western boundary of the United States, and, but for the indomitable persevering opposition of John Adams, one of the American commissioners, who insisted upon the Mississippi River as the boundary, this proposition would have probably been acceded to.

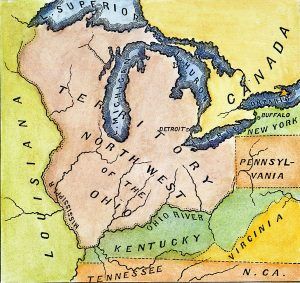

The states that owned western unappropriated lands under their original charters from British monarchs, with a single exception, ceded them to the United States. In March 1784, Virginia ceded the soil and jurisdiction of her lands northwest of the Ohio River. In September 1786, Connecticut ceded her claim to the soil and jurisdiction of her western lands, except that part of the Ohio River known as the “Western Reserve,” To that, she ceded her jurisdictional claims in 1800. Massachusetts and New York ceded all their claims. Besides these were the Indian claims asserted by the right of possession. Various treaties have extinguished these from time to time, as the inroads of emigration were rendered necessary.

The Indian title to a large part of the territory of Ohio had been extinguished. Before settlements were commenced, Congress found it necessary to pass ordinances for surveying and selling the lands in the Northwest Territory. In October 1787, Manasseh Cutler and Winthrop Sargeant, agents of the New England Ohio Company, made a large purchase of land bounded south by the Ohio River and west by the Scioto River. Its settlement commenced at Marietta in the spring of 1788, the first made by the Americans within Ohio. A settlement had been attempted within the limits of Ohio, on the site of Portsmouth, in April 1785 by four families from Redstone, Pennsylvania. However, difficulties with the Indians compelled its abandonment.

About the time of the settlement of Marietta, Congress appointed General Arthur St. Clair, Governor; Winthrop Sargeant, Secretary; Samuel Holden Parsons, James M. Varnum, and John Cleves Symmes, Judges in and over the Territory. They organized its government and passed laws, and the governor erected the county of Washington, embracing nearly the eastern half of the present limits of Ohio.

In November 1788, the second settlement within the limits of Ohio was commenced at Columbia, on the Ohio River, five miles above the site of Cincinnati, and within the purchase and under the auspices of John Cleves Symmes and associates. Within Symmes’s purchase, settlements were commenced at Cincinnati and North Bend, 16 miles below. In 1790, another settlement was made at Gallipolis by a colony from France — the name signifying the city of the French.

On January 9, 1789, a treaty was concluded at Fort Harmer, at the mouth of the Muskingum River, opposite Marietta, by Governor St. Clair, in which the treaty, which had been made four years previous, at Fort McIntosh, on the site of Beaver, Pennsylvania, was renewed and confirmed. It did not, however, produce the favorable results anticipated. The Indians, the same year, committed numerous murders, which occasioned the alarmed settlers to erect block houses in each new settlement. In June, Major Doughty, with 140 men, commenced the erection of Fort Washington on the site of Cincinnati. General Josiah Harmer arrived at the Fort with 300 men during the summer.

Negotiations with the Indians proved unfavorable; General Josiah Harmer marched in September 1790 from Cincinnati with 1,300 men, less than one-fourth of whom were regulars, to attack their towns on the Maumee River. He succeeded in burning their towns, but in an engagement with the Indians, part of his troops met with a severe loss. The following year, a larger army was assembled at Cincinnati under General St. Clair, comprising about 3,000 men. With this force, he commenced his march toward the Indian towns on the Maumee River. Early in the morning of November 4, 1791, his army, while in camp on what is now the line of Darke and Mercer Counties, within three miles of the Indiana line and about 70 miles north of Cincinnati, was surprised by a large body of Indians, and defeated with terrible slaughter. A third army, under General Anthony Wayne, was organized. On August 20, 1794, they met and ultimately defeated the Indians on the Maumee River, about 12 miles south of the site of Toledo. The Indians, at length, becoming convinced of their inability to resist the American arms, sued for peace. On August 3, 1795, General Wayne concluded a treaty at Greenville, sixty miles north of Cincinnati, with eleven powerful northwestern tribes in a grand council. This gave peace to the West for several years, during which the settlements progressed rapidly. Jay’s Treaty, which concluded November 19, 1794, was a most important event to the prosperity of the West. It provided for the withdrawal of all the British troops from the northwestern posts. In 1796, the Northwestern Territory was divided into five counties. Marietta was the seat of justice of Hamilton and Washington counties; Vincennes of Knox County; Kaskaskia of St. Clair County; and Detroit of Wayne County. The settlers, out of the limits of Ohio, were Canadian or Creole French. The headquarters of the Northwest army were removed to Detroit, at which point a fort had been built by De la Motte Cadillac as early as 1701.

Initially, Virginia claimed jurisdiction over a large part of Western Pennsylvania as being within her dominions. Yet, it was not until after the close of the American Revolution that the boundary line was permanently established.

Then this tract was divided into two counties. Westmoreland extended from the mountains west of the Alleghany River, including Pittsburgh, and the entire country between the Kishkeminitas and the Youghiogheny Rivers. The other, Washington, is comprised of all south and west of Pittsburgh, including all the country east and west of the Monongahela River.

At this period, Fort Pitt was a frontier post that had sprung up the village of Pittsburgh, which was not regularly laid out into a town until 1784. The settlement on the Monongahela at “Redstone Old Fort,” or “Fort Burd,” as it originally was called, having become an important point of embarkation for western emigrants, was the following year laid off into a town under the name of Brownsville. Regular forwarding houses were soon established here, by whose lines goods were systematically wagoned over the mountains, thus superseding the slow and tedious mode of transportation by pack-horses, to which the emigrants had previously been obliged to resort.

In July 1786, The Pittsburgh Gazette, the first newspaper issued in the West, was published; the second was the Kentucky Gazette, established at Lexington in August of the following year. As late as 1791, the Alleghany River was the frontier limit of the settlements of Pennsylvania, the Indians holding possession of the region around its northwestern tributaries, except for a few scattering settlements, which were all simultaneously broken up and exterminated in one night in February of this year, by a band of 150 Indians. Pittsburgh was the army’s great depot during the Harmer, St. Clair, and Wayne campaigns.

By this time, agriculture and manufacturing had begun to flourish in western Pennsylvania and Virginia, and extensive trade was carried on with the settlements on the Ohio River and the lower Mississippi River, with New Orleans and the rich Spanish settlements in its vicinity. Monongahela whiskey, horses, cattle, and agricultural and mechanical implements of iron were the principal export articles. Soon after, the Spanish government embarrassed this trade by imposing heavy duties. The first settlements in Tennessee were made near Fort Loudon, on the Little Tennessee River, in Monroe County, East Tennessee, in about 1758. Forts Loudon and Chiswell were built by Colonel Byrd, who marched into the Cherokee country with a regiment from Virginia. The following year, war broke out with the Cherokee. In 1760, the Cherokee besieged Fort Loudon, where the settlers had gathered their families, numbering nearly 300 persons. The latter was obliged to surrender for want of provisions but, agreeably to the terms of capitulation, were to retreat unmolested beyond the Blue Ridge. When they had proceeded about 20 miles on their route, the Indians fell upon them and massacred all but nine, not even sparing the women and children.

This war thus broke up the only settlements. The following year, the celebrated Daniel Boone made an excursion from North Carolina to the waters of the Holstein River. In 1766, Colonel James Smith and five others traversed a significant portion of Middle and West Tennessee. At the mouth of the Tennessee River, Smith’s companions left him to explore farther in Illinois. At the same time, in company with an African-American lad, he returned home through the wilderness after an absence of eleven months, during which he saw “neither bread, money, women, nor spirituous liquors.”

Other explorations soon succeeded, and permanent settlements were first made in 1768 and 1769 by emigrants from Virginia and North Carolina, who were scattered along the branches of the Holstein, French Broad, and Watauga Rivers. The jurisdiction of North Carolina was extended in 1777 over the Western District, which was organized as the county of Washington and extended westward to the Mississippi River. Soon after, some more daring pioneers settled at Bledsoe’s Station in Middle Tennessee, in the heart of the Chickasaw Nation. They separated several hundred miles, by the usually traveled route, from their kinsmen on the Holstein.

Several French traders had previously established a trading post and erected a few cabins at the “Bluff” near the site of Nashville. To the same vicinity, Colonel James Robertson, in the fall of 1780, emigrated with 40 families from North Carolina, who were driven from their homes by the marauding incursions of Tarleton’s cavalry, and established “Robertson’s Station,” which formed the nucleus around which gathered the settlements on the Cumberland. The Cherokee, having commenced hostilities upon the frontier inhabitants about the commencement of the year 1781, Colonel Campbell of Virginia, with 700 mounted riflemen, invaded their country and defeated them. At the close of the American Revolution, settlers moved in large numbers from Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia. Nashville was laid out in the summer of 1784 and named after General Francis Nash, who fell at Brandywine.

The people of this district, in common with those of Kentucky and on the tipper Ohio River, were deeply interested in navigating the Mississippi River. Under the tempting offers of the Spanish governor of Louisiana, many were lured to emigrate to West Florida and become subjects of the Spanish.

North Carolina, having ceded her claims to her western lands, Congress, in May 1790, erected this into a territory under the name of the “Southwestern Territory,” according to the provisions of the ordinance of 1787, excepting the article prohibiting slavery.

The territorial government was organized by a legislature and a legislative council, with William Blount as their first governor. Knoxville was made the seat of government. A fort was erected to intimidate the Indians by the United States in the Indian country on the site of Kingston. From this period until the final overthrow of the northwestern Indians by Wayne, this territory suffered from the hostilities of the Creek and Cherokee, who were secretly supplied with arms and ammunition by the Spanish agents, with the hope that they would exterminate the Cumberland settlements. In 1795, the territory contained a population of 27,262, of whom about 10,000 were slaves. On June 1, 1796, it was admitted into the Union as the State of Tennessee.

By the treaty of October 27, 1795, with Spain, the old sore, the right to navigate the Mississippi River, was closed, and that power ceded to the United States the right of free navigation.

The Territory of Mississippi was organized in 1798, and Winthrop Sargeant was appointed Governor. By the ordinance of 1787, the people of the Northwest Territory were entitled to elect Representatives to a Territorial Legislature whenever it contained 5,000 males of full age. Before the close of 1798, the Territory had this number, and members of a Territorial Legislature were soon chosen. In 1799, William H. Harrison was chosen as the first delegate to Congress from the Northwest Territory. In 1800, the Territory of Indiana was formed, and the following year, William H. Harrison was appointed Governor. This Territory comprised the states of Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan, a vast country with less than 6,000 whites, mainly of French origin. On April 30, 1802, Congress passed an act authorizing a convention to form a constitution for Ohio. This convention met at Chillicothe in the succeeding November, and on the 29th of that month, a constitution of the State Government was ratified and signed. That act made Ohio one of the States of the Federal Union. In October 1802, the whole western country was thrown into a ferment by suspending the American right to deposit goods and produce at New Orleans, guaranteed by the treaty of 1795 with Spain. Western commerce was struck at a vital point, and the treaty was violated. On February 25, 1803, the port was opened to provisions on paying a duty, and in April following, by orders of the King of Spain, the right of deposit was restored.

After the treaty of 1763, Louisiana remained in possession of Spain until 1803, when it was again restored to France by the terms of a secret article in the treaty of St. Ildefonso concluded with Spain in 1800. France held but brief possession; on April 30, she sold her claim to the United States for the consideration of $15,000,000. On December 20, General Wilkinson and Claiborne took possession of the country for the United States and entered New Orleans at the head of the American troops.

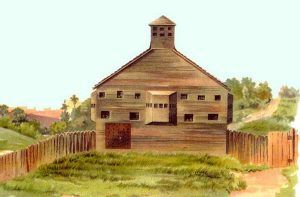

On January 11, 1805, Congress established the Territory of Michigan and appointed William Hull governor. This same year, Detroit was destroyed by fire. The town occupied only about two acres, wholly covered with buildings and combustible materials, except the narrow intervals of fourteen or fifteen feet used as streets or lanes. A strong and secure defense of tall and solid pickets surrounded the whole.

During this period, the conspiracy of Aaron Burr began to agitate the western country. In December 1806, a fleet of boats, with arms, provisions, and ammunition, belonging to the confederates of Burr, were seized, upon the Muskingum, by agents of the United States, which proved a fatal blow to the project. In 1809, the Territory of Illinois was formed from the western part of the Indiana Territory and named for the powerful tribe that once occupied its soil.

The Indians, who, since the Treaty of Greenville, had been at peace about 1810, began to commit aggressions upon the inhabitants of the west under the leadership of Tecumseh. The following year, they were defeated by General Harrison at the Battle of Tippecanoe in Indiana. This year was also distinguished by the voyage from Pittsburgh to New Orleans of the steamboat New Orleans, the first steamer ever launched upon the western waters.

In June 1812, the United States declared war against Great Britain. In this war, the West was the principal theater. Its opening scenes were as gloomy and disastrous to the American arms as its close was brilliant and triumphant.

At the close of the war, the population of the Territories of Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan was less than 50,000. But, from that time onward, emigration went forward with unprecedented rapidity. On April 19, 1816, Indiana was admitted into the Union, and Illinois on December 3, 1818. The remainder of the Northwest Territory, as then organized, was included in the Territory of Michigan, of which that section west of Lake Michigan bore the name of the Huron District. This part of the west increased so slowly that, by the census of 1830, the Territory of Michigan contained, exclusive of the Huron District, but 28,000 souls, while that had only a population of 3,640. Emigration began to set in more strongly to the Territory of Michigan because steam navigation had been successfully introduced upon the great lakes of the west. The first steamboat upon these immense inland seas was the Walk-in-the-Water, which, in 1819, went as far as Mackinaw; yet, it was not until 1826 that a steamer rode the waters of Lake Michigan, and six years more had elapsed before one had penetrated as far as Chicago, Illinois.

The year 1832 was signalized by three important events in the history of the West — the first appearance of the Asiatic Cholera, the Great Flood in the Ohio River, and the Black Hawk War.

The West has suffered serious drawbacks in its progress from inefficient banking systems. One bank frequently was made the basis of another, and that of a third, and so on throughout the country. In establishing a bank, some three or four shrewd agents or directors would collect a few thousand in specie that had been honestly paid in and then make up the remainder of the capital with the bills or stock from some neighboring bank. Thus, each bank’s connection with others was so intimate that when one or two gave way, they all went down together in one common ruin.

In 1804, the year preceding the Louisiana Purchase, Congress formed from part of it the “Territory of Orleans,” which was admitted into the Union in 1812 as the State of Louisiana. In 1805, after the Territory of Orleans was erected, the remaining part of the purchase from the French was formed into the Territory of Louisiana, of which the old French town of St. Louis was the capital. This town, the oldest in the Territory, had been founded in 1764 by M. Laclede, agent for a trading association, to whom had been given, by the French government of Louisiana, a monopoly of the commerce in furs and peltries with the Indian tribes of the Missouri and upper Mississippi Rivers. The Territory’s population in 1805 was inconsequential and consisted mainly of French Creole and traders scattered along the banks of the Mississippi and the Arkansas Rivers. Upon admission to Louisiana as a state, the name of the Territory of Louisiana was changed to Missouri. From the southern part of this, in 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was erected, which then contained but a few thousand inhabitants, who were mainly in detached settlements on the Mississippi and the Arkansas Rivers in the vicinity of the “Post of Arkansas.” The first settlement in Arkansas was made on the Arkansas River in about 1723, upon the grant of the notorious John Law, but, being unsuccessful, it was soon abandoned. In 1820, Missouri was admitted into the Union, and Arkansas in 1836.

Michigan was admitted as a State in 1837. The Huron District was organized as the Wisconsin Territory in 1836 and was admitted into the Union as a State in 1848. The first settlement in Wisconsin was made in 1665, when Father Claude Allouez established a mission at La Pointe, at the western end of Lake Superior. Four years later, a mission was permanently established at Green Bay, and eventually, the French established themselves at Prairie du Chien. In 1819, an expedition under Governor Cass explored the territory and found it to be little more than the abode of a few Indian traders scattered here and there. At about this time, the Government established military posts at Green Bay and Prairie du Chien. About 1825, some farmers settled near Galena, which became a noted mineral region. Immediately after the war with Black Hawk, emigrants flowed in from New York, Ohio, and Michigan, and the flourishing towns of Milwaukee, Sheboygan, Racine, and Southport were laid out on the borders of Lake Michigan. After the same war, the lands west of the Mississippi River were thrown open to emigrants, who commenced settlements near Fort Madison and Burlington in 1833. Dubuque had long before been a trading post and the first settlement in Iowa. It derived its name from Julien Dubuque, an enterprising French Canadian who, in 1788, obtained a grant of 140,000 acres from the Indians, upon which he resided until he died in 1810 when he had accumulated immense wealth by lead mining and trading. In June 1838, Iowa was erected into a Territory, and in 1846, it became a State.

In 1849, Minnesota Territory was organized; it contained a little less than 5,000 souls. The first American establishment in the Territory was Fort Snelling, at the mouth of St. Peters, or Minnesota River, founded in 1819. The French and the English occupied this country with their fur trading forts. Pembina, on the northern boundary, is the oldest village, established in 1812 by Lord Selkirk, a Scottish nobleman, under a Hudson’s Bay Company grant.

But, here, the adventurous spirit of emigration does not pause. The blue waters of the far distant Pacific were the only barrier to the never-ceasing human tide. The rich valleys of Oregon and the golden sands of California became the lures to attract thousands from the comforts of home, civilization, and refinement in search of fortune and independence in distant wilds.

By Henry Howe, 1857 – Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025

Also See:

Adventures in the American West

Westward Expansion & Manifest Destiny

About the Author and Article: This article was a chapter in Henry Howe’s book Historical Collections of the Great West, published by George F. Tuttle of New York in 1857. Henry Howe (1816 -1893) was an author, publisher, historian, and bookseller. Born in New Haven, Connecticut, his father owned a popular bookshop and a publisher. Henry would write histories of several states. His most famous work was the three-volume Historical Collections of Ohio. As he collected facts for his writing, he drew sketches, which helped create interest in his work. The article as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been edited for the modern reader; however, the content essentially remains the same.