By George Ward Nichols, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867

This article, written by George Ward Nichols, was excerpted, in part, from an article that appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, entitled Wild Bill, in February 1867, now in the public domain. The article is not verbatim, as glaring errors, such as Nichols referring to Bill Hickok as William Hitchcock, and other grammatical and spelling corrections have been made. In addition, it was widely criticized as exaggerating Bill Hickok’s deeds, defaming the people of Springfield, Missouri, including numerous downright inaccuracies. You can read about the criticisms after this article.

~~

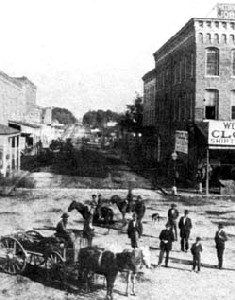

Several months after the end of the Civil War, I visited Springfield, a city in southwest Missouri. Springfield is not a burgh of extensive dimensions, yet it is the largest in that part of the State, and all roads lend to it — which is one reason why it was the point of support and the base of operations for all military movements during the war.

On a warm summer day, I sat watching from the shadow of a broad awning the comings and goings of the strange, half-civilized people who, from all the country round, make this a place for barter and trade. Men and women dressed in queer costumes; men with coats and trousers made of skin but so thickly covered with dirt and grease as to have defied the identity of the animal when walking in the flesh. Others wore homespun gear, which oftentimes appeared to have seen lengthy service. Many of those people were mounted on horse-hack or mule-back, while others urged forward the unwilling cattle attached to creaking, heavily laden wagons, their drivers snapping their long whips with a report like that of a pistol shot.

In front of the shops, which lined both sides of the central business street and about the public square, were groups of men lolling against posts, lying upon the wooden sidewalks, or sitting in chairs. These men were temporary or permanent denizens of the city and were lazily occupied in doing nothing. The most marked characteristic of the inhabitants seemed to be an indisposition to move and their highest ambition to let their hair and beards grow.

Here and there, upon the street, the appearance of the army blue betokened the presence of a returned Union soldier, and the jaunty, confident air with which they carried themselves was all the more striking in its contrast with the indolence which appeared to belong to the place. The only indication of action was the inevitable revolver, which everybody, except, perhaps, the women, wore about their persons. When people moved into this lazy city, they did so slowly and without method. No one seemed in baste. A huge hog wallowed in luxurious ease in a nice bed of mud on the other side, giving vent to gentle grunts of satisfaction. On the platform at my feet lay a large wolf-dog asleep with one eye open. He, too, seemed contented to let the world wag idly on.

The loose, lazy spirit of the occasion finally took possession of me, and I sat and gazed and smoked. I might have fallen into a Rip Van Winkle sleep to have been aroused ten years hence by the cry, “Passengers for the flying machine to New York, all aboard!” when I and the drowsing city were roused into life by the clatter and crash of the hoofs of a horse which dashed furiously across the square and down the street. The rider sat perfectly erect, yet following with grace of motion, seen only in the horsemen of the plains, the rise and fall of the galloping steed. There was only a moment to observe this, for they halted suddenly, while the rider springing to the ground approached the party which the noise had gathered near me.

“This yere is Wild Bill, Colonel,” said Captain Honesty, an army officer, addressing me.

He continued:

“How are yer, Bill? This yere is Colonel N____, who wants ter know yer.”

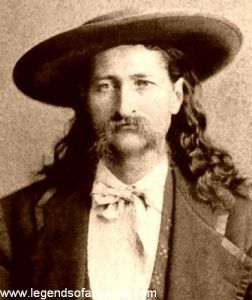

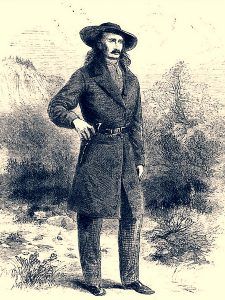

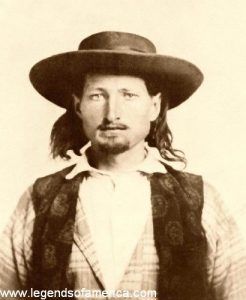

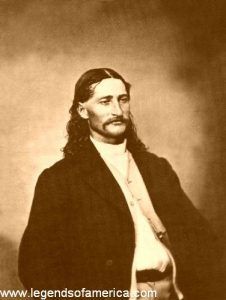

Let me at once describe the personal appearance of the famous Scout of the Plains, William Hickok, called “Wild Bill,” who now advanced toward me, fixing his clear gray eyes on mine quickly, interrogatively as if to take my measure.

The result seemed favorable, for he held forth a small, muscular hand in a frank, open manner. Looking at him, I thought he was the most handsome physique I had ever seen. In its exquisite manly proportions, it recalled the antique. It was a figure Ward would delight to model as a companion to his Indian.

Bill stood six feet and an inch in his bright yellow moccasins. A deer-skin shirt, or frock it might be called, hung jauntily over his shoulders, revealing a chest whose breadth and depth were remarkable. These lungs had grown in some 20 years of the free air of the Rocky Mountains. His small, round waist was girthed by a belt that held two of Colt’s Navy revolvers.

His legs sloped gradually from the compact thigh to the feet, which were small, and turned inward as he walked. There was a singular grace and dignity of carriage about that figure which would have called your attention to meet it where you would. The head which crowned it was now covered by a large sombrero, underneath which there shone out a quiet, manly face; so gentle is its expression as he greets you as utterly to belie the history of its owner, yet it is not a face to be trifled with.

The lips thin and sensitive, the jaw not too square, the cheekbones slightly prominent, a mass of fine dark hair falls below the neck to the shoulders. The eyes, now that you are in friendly intercourse, are as gentle as a woman’s.

In truth, the woman’s nature seems prominent throughout, and you would not believe that you were looking into eyes that have pointed the way to death to hundreds of men. Yes, Wild Bill, with his own hands, has killed hundreds of men. Of that, I have no doubt. He shoots to kill, as they say, on the border.

In vain did I examine the scout’s face for some evidence of murderous propensity. It was a gentle face, and singular only in the sharp angle of the eye, and without any physical reason for the opinion, I have thought this peculiarity indicated his astounding accuracy of aim. He told me, however, to use his own words:

“I allers shot well, but I come to be perfect in the mountains by shooting at a dime for a mark, at bets of half a dollar a shot. And then, until the war, I never drank liquor nor smoked,” he continued, with a melancholy expression; “war is demoralizing, it is.”

Captain Honesty was right. I was very curious to see “Wild Bill, the Scout,” who, a few days before I arrived in Springfield, in a duel at noonday in the public square, at 50 paces, had sent one of Colt’s pistol balls through the heart of a returned Confederate soldier.

Whenever I had met an officer or soldier who had served in the Southwest, I heard of Wild Bill and his exploits until these stories became so frequent and of such an extraordinary character as quite to outstrip personal knowledge of adventure by camp and field and the hero of these strange tales took shape in my mind as did Jack the Giant Killer or Sinbad the Sailor in childhoods days. As then, I now had the most implicit faith in the individual’s existence; however, how one man could accomplish such prodigies of strength and feats of daring was a continued wonder.

To give the reader a clearer understanding of the condition of this neighborhood, which could have permitted the duel mentioned above and whose history will be given hereafter in detail, I will describe the situation at the time of which I am writing, which was late in the summer of 1865, premising that this section of the country would not today be selected as a model example of modern civilization.

At that time, peace and comparative quiet succeeded the perils and tumult of war in the Southern states. The people of Georgia and the Carolinas were glad to enforce order in their midst, and it would have been safe for a Union officer to have ridden unattended through the land.

In Southwest Missouri, there were old scores to be settled up. During the three days occupied by General Smith, who commanded the Department and was on a tour of inspection in crossing the country between Rolla and Springfield, a distance of 120 miles, five men were killed or wounded on the public road. Two were murdered a short distance from Rolla — by whom we could not ascertain. Another was instantly killed, and two were wounded at a meeting of a band of Regulators who were in the service of the State but were paid by the United States Government. It should be said here that their method of “regulation” was slightly informal, their war-cry was, “A swift bullet and a short rope for returned rebels!”

I was informed by General Smith that during the six months preceding, not less than 4,000 returned Confederates had been summarily disposed of by shooting or hanging. This statement seems incredible, but there is the record, and I do not doubt its truth. History shows few parallels to this relentless destruction of human life in a time of peace. It can’t be explained only on the ground that, before the war, this region was inhabited by lawless people. At the outset of the rebellion, the merest suspicion of loyalty to the Union cost the patriot his life; thus, large numbers fled the land, giving up their homes and every material interest. As soon as the Federal armies occupied the country, these refugees returned.

Once securely fixed in their old homes, they resolved that their former persecutors should not live in their midst. Revenge for the past and security for the future knotted many a nerve and sped many a deadly bullet.

Wild Bill did not belong to the Regulators. Indeed, he was one of the law and order party. He said:

“When the war closed, I buried the hatchet, and I won’t fight now unless I’m put upon.”

Bill was born to Northern parents in the State of Illinois. He ran away from home when a boy wandered out upon the plains and into the mountains. For 15 years, he lived with the trappers, hunting and fishing. When the war broke out, he returned to the States and entered the Union service. No man probably was ever better fitted for scouting than he. Joined to his tremendous strength, he was an unequaled horseman, a perfect marksman, a keen sight, and a constitution that had no limit of endurance. He was calm to audacity, brave to rashness, always possessed of himself under the most critical circumstances, and, above all, was such a master in the knowledge of woodcraft that it might have been termed a science with him — a knowledge which, with the soldier, is priceless beyond description. Some of Bill’s adventures during the war will be related hereafter.

The main features of the story of the duel were told by Captain Honesty, who was unprejudiced if it was possible to find an unbiased mind in a town of 3,000 people after a fight. I will give the story in his words:

“They say Bill’s wild. Now he isn’t any sich thing. I’ve known him goin on ter ten year, and he’s as civil a disposed person as you’ll find he-e-arabouts. But he won’t be put upon.”

“I’ll tell yer how it happened. But come inter the office; thar’s a good many round hy’ar as sides with Dave Tutt— the man that’s shot. But I tell yer ’twas a ‘far fight. Take some whisky? No! Well, I will, if yer’l excuse me.”

“You see,” continued the Captain, setting the empty glass on the table in an emphatic way, “Bill was up in his room a-playin seven-up, or four-hand, or some of them pesky games. Bill refused ter play with Tutt, who was a professional gambler. You see, Bill was a scout on our side during the war, and Tutt was a reb scout. Bill had killed Dave Tutt’s mate, and, atween one thing and another, there war an unusual hard feelin atwixt ‘em.”

“Ever since Dave came back, he had tried to pick a row with Bill, so Bill wouldn’t play cards with him anymore. But Dave stood over the man gambling with Bill and lent the feller money. Bill won bout $200, which made Tutt spiteful mad. Bime-by, he says to Bill:

‘Bill you’ve got plenty of money — pay me that $40 yer owe me in that horse trade.’

“And Bill paid him.” Then he said:

‘Yer owe me $35 more; yer lost it playing with me t’other night.’

“Dave’s style was right provoking, but Bill answered him perfectly gentlemanly:

‘I think yer wrong, Dave. It’s only $25. I have a memorandum of it in my pocket downstairs. Ef its $35 I’ll give it yer.’”

“Now Bill’s watch was lying on the table. Dave took up the watch, put it in his pocket,

and said: ‘I’ll keep this yere watch till yer pay me that $35.’”

“This made Bill shooting mad; fur, don’t yer see, Colonel, it was a-doubting his honor like, so he got up and looked Dave in the eyes, and said to him: ‘I don’t want ter make a row in this house. It’s a decent house, and I don’t want ter injure the keeper. You’d better put that watch back on the table.’”

“But Dave grinned at Bill mighty ugly, and walked off with the watch, and kept it several days. All this time Dave’s friends were spurring Bill on ter fight; there was no end ter the talk. They blackguarded him in an underhand sort of a way and tried to get up a scrimmage, and then they thought they could lay him out. Yer see Bill has enemies all about; he’s settled the accounts of a heap of men who lived round here. This is about the only place in Missouri whar a reb can come back and live, and to tell yer the truth, Colonel –” and the Captain, with an involuntary movement, hitched up his revolver belt, as he said, with expressive significance, “they don’t stay long round here!”

“Well, as I was saying, these rebs don’t like ter see a man walking round town who they knew in the reb army as one of their men, who they now know was on our side, all the time he was sending us information, sometimes from Pap Price’s own headquarters. But they couldn’t provoke Bill inter a row, for he’s afeard of himself when he gits awful mad, and he allers left his shooting irons in his room when he went out. One day these cusses drew their pistols on him and dared him to fight, and then they told him that Tutt was a-goin ter pack that watch across the square next day at noon.”

“I heard of this, for everybody was talking about it on the street, and so I went after Bill and found him in his room cleaning and greasing and loading his revolvers.”

“Now, Bill, says I, ‘you’re goin ter git inter a fight.’”

“Don’t you bother yerself Captain,’ says he. ‘It’s not the first time I have been in a fight, and these d—d hounds have put on me long enough. You don’t want me ter give up my honor, do yer?’”

‘No, Bill,’ says I, ‘yer must keep yer honor.’”

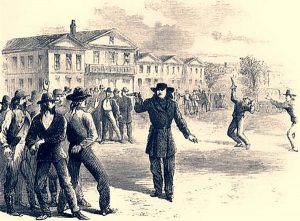

“Next day, about noon, Bill went down on the square. He had said that Dave Tutt shouldn’t pack that watch across the squar unless dead men could walk.”

“When Bill got onter the squar he found a crowd stanin in the corner of the street by which he entered the square, which is from the south yer know. In this crowd, he saw a lot of Tutt’s friends; some were cousins of his’n, just back from the reb army, and they jeered him and boasted that Dave was a-goin to pack that watch across the square as he promised.”

“Then Bill saw Tutt stain near the courthouse, which yer remember is on the west side, so that the crowd was behind Bill.”

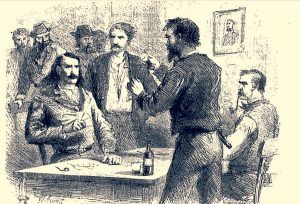

“Just then, Tutt, who was alone, started from the courthouse and walked out into the square, and Bill moved away from the crowd toward the west side of the square. Bout 15 paces brought them opposite to each other, and bout 50 yards apart. Tutt then showed his pistol. Bill had kept a sharp eye on him, and before Tutt could pint it, Bill had his’n out.”

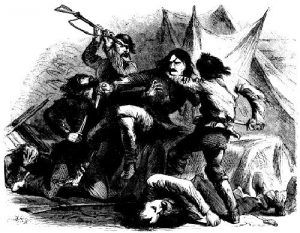

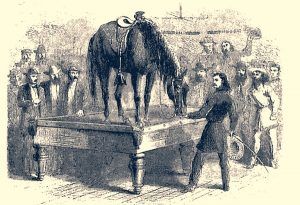

After the Springfield, Missouri shoot-out, Hickok turned on Tutt’s friends, illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

“At that moment you could have heard a pin drop in that square. Both Tutt and Bill fired, but one discharge followed the other so quickly that it’s hard to say which went off first. Tutt was a famous shot, but he missed this time; the ball from his pistol went over Bill’s head. The instant Bill fired, without waitin ter see ef he had hit Tutt, he wheeled on his heels and pointed his pistol at Tutt’s friends, who had already drawn their weapons.

“‘Aren’t yer satisfied, gentlemen?’ cried Bill, as cool as an alligator. ‘Put up your shooting-irons, or there’ll be more dead men here. And they put ‘em up and said it was a far fight.”

“What became of Tutt?” I asked of the Captain, who had stopped at this point of his story and was very deliberately engaged in refilling his empty glass.”

“Oh! Dave? He was as plucky a feller as ever drew trigger, but, Lord bless yer! it was no use. Bill never shoots twice at the same man, and his ball went through Dave’s heart. He stood stock-still for a second or two, then raised his arm as if ter fire again, then he swayed a little, staggered three or four steps, and then fell dead.”

“Bill and his friends wanted ter have the thing done regular, so we went up ter the Justice, and Bill delivered himself up. A jury was drawn; Bill was tried and cleared the next day. It was proved that it was a case of self-defense. Don’t yer see, Colonel?”

I answered that I was afraid that I did not see that point very clearly.

“Well, well!” he replied, with an air of compassion; you haven’t drunk any whisky; that’s what’s the matter with yer.” And then, putting his hand on my shoulder with a half-mysterious, half-conscious look in his face, he muttered, in a whisper:

“The fact is, thar was an undercurrent of a woman in that fight!”

The story of the duel was yet fresh from the lips of the Captain when its hero appeared in the manner already described. After a few moments conversation, Bill excused himself, saying:

“I am going out on the prarer a piece to see the sick wife of my mate. I should be glad to meet yer at the hotel this afternoon, Kernel.”

“I will go there to meet you,” I replied.

“Good day, gentlemen,” said the scout as he saluted the party, and mounting the black horse standing quiet, unhitched, he waved his hand over the animal’s head. Responsive to the signal, she shot forward as the arrow left the bow, and they both disappeared up the road in a cloud of dust.

I went to the hotel during the afternoon to keep the scout’s appointment. The large room of the hotel in Springfield is perhaps the central point of attraction in the city. It fronted on the street and served in several capacities. It was a sort of exchange for those who had nothing better to do than to go there. It was a reception room, parlor, and office, but its distinguished and most fascinating characteristic was the bar, which occupied one entire end of the apartment. Technically, the “bar” is the counter upon which the polite official places his viands. The bar is represented in the long rows of bottles, cut-glass decanters, and the glasses and goblets of all shapes and sizes suited to the various liquors to be imbibed. It was a charming and artistic display of elongated transparent vessels containing every known drinkable fluid, from native Bourbon to imported Lacryma Christi!

The room, in its way, was a temple of art. All sorts of pictures budded and blossomed and blushed from the walls. Sixpenny portraits of the Presidents encoffined in pine-wood frames; Mazeppa appeared in the four phases of his celebrated one-horse act, while a lithograph of “Mary Ann” smiled and simpered despite the stains of tobacco juice which had been unsparingly bestowed upon her countenance. But the hanging committee of this un-designed academy seemed to have been prejudiced as all hanging committees of good taste might well be — in favor of Harper’s Weekly, for the walls of the room were well covered with woodcuts cut from that journal. Portraits of noted generals and statesmen, knaves and politicians, with bounteous illustrations of battles and skirmishes, from Bull Run number one to Dinwiddie Court House. And the simple-hearted comers and goers of Springfield looked upon, wondered, and admired these pictorial descriptions fully as much as if they had been the masterpieces of a Yvon or Vernet.

A billiard table, old and out of use, where caroms seemed to have been made quite as often with lead as ivory balls, stood in the center of the room. A dozen chairs filled up the complement of the furniture. The appearance of the party of men assembled there, who sat with their slovenly shod feet dangling over the arms of the chairs or hung about the porch outside, was in perfect harmony with the time and place.

All of them religiously obeyed the two before-mentioned characteristics of the city’s people — their hair was long and tangled, and each man fulfilled the most exalted requirement of laziness.

I was taking a mental inventory of all this when a cry and murmur drew my attention to the outside of the house when I saw Wild Bill riding up the street at a swift gallop. Arrived opposite to the hotel, he swung his right arm around with a circular motion. Black Nell instantly stopped and dropped to the ground as if a cannonball had knocked the life out of her. Bill left her there, stretched upon the ground, and joined the group of observers on the porch.

“Black Nell hasn’t forgotten her old tricks,” said one of them.

“No,” answered the scout. “God bless her! She is wiser and truer than most men I know of. That mare will do any thing for me. Won’t you, Nelly?” The mare winked affirmatively the only eye we could see.

Black Nell, Bill Hickok’s horse, climbs on a billiard table at Hickok’s command, illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

“Wise!” continued her master; “why, she knows more than a judge. I’ll bet the drinks for the party that sh’ell walk up these steps and into the room and climb up on the billiard table and lie down.”

The bet was taken at once, not because anyone doubted the capabilities of the mare, but there was excitement in the thing without exercise.

Bill whistled in a low tone. Nell instantly scrambled to her feet, walked toward him, put her nose affectionately under his arm, followed him into the room, and, to my extreme wonderment, climbed upon the billiard-table, to the extreme astonishment of the table no doubt, for it groaned under the weight of the four-legged animal and several of those who were simply bifurcated, and whom Nell permitted to sit upon her. When she got down from the table, which was as graceful performance as might be expected under the circumstances, Bill sprang upon her back, dashed through the high, wide doorway, and at a single bound cleared the flight of steps and landed in the middle of the street.

The scout then dismounted, snapped his riding-whip, and the noble beast bounded off down the street, rearing and plunging to her own intense satisfaction. A kindly-disposed individual, who must have been a stranger, supposing the mare was running away, tried to catch her when she stopped, and as if she resented his impertinence, let fly her heels at him and then quietly trotted to her stable.

“Black Nell has carried me along through many a tight place,” said the scout, as we walked toward my quarters. “She trains easier than any animal I ever saw. That trick of dropping quick which you saw has saved my life and again. When I have been out scouting on the prairie or in the woods I have come across parties of rebels, and have dropped out of sight in the tall grass before they saw us. One day a gang of rebs who had been hunting for me, and thought they had my track, halted for half an hour within 50 yards of us. Nell laid as close as a rabbit and didn’t even whisk her tail to keep the flies off; until the rebs moved off, supposing they were on the wrong scent. The mare will come at my whistle and foller me about just like a dog. She won’t mind anyone else, nor allow them to mount her, and will kick a harness and wagon all ter pieces ef you try to hitch her in one. And she’s right, Kernel,” added Bill, with the enthusiasm of a true horse lover sparkling in his eyes. “A hoss is too noble a beast to be degraded by such toggery. Harness mules and oxen, but give a hoss a chance ter run.”

I had a curiosity, which was not an idle one, to hear what this man had to say about his duel with Tutt, and I asked him:

“Do you not regret killing Tutt? You surely do not like to kill men?”

“As ter killing men,” he replied, “I never thought much about it. Most of the men I have killed it was one or the other of us, and at sich times you don’t stop to think; and what’s the use after it’s all over? As for Tutt, I had rather not have killed him, for I want ter settle down quiet here now. But thar’s been hard feeling between us a long while. I wanted ter keep out of that fight; hut he tried to degrade me, and I couldn’t stand that, you know, for I am a fighting man, you know.”

A cloud passed over the speaker’s face for a moment as he continued:

“And there was a cause of quarrel between us which people around here don’t know about, One of us had to die, and the secret died with him.”

“Why did you not wait to see if your ball had hit him? Why did you turn round so quickly?”

The scout fixed his gray eyes on mine, striking his leg with his riding-whip, as he answered, “I knew he was a dead man. I never miss a shot. I turned on the crowd because I was sure they would shoot me if they saw him fall.”

“The people about here tell me you are a quiet, civil man. How is it you get into these fights?”

“D—-d if I can tell,” he replied, with a puzzled look which at once gave place to a proud defiant expression as he continued – “but you know a man must defend his honor.”

“Yes, I admitted, with some hesitation, remembering that I was not in Boston but on the border and that the code of honor and mode of redress differ slightly in the one place from those of the other.

One of the reasons for my desire to make the acquaintance of Wild Bill was to obtain from his own lips a true account of some of the adventures related to him. It was not an easy matter. It was hard to overcome the reticence which marksmen who have lived the wild mountain life, and which was one of his valuable qualifications as a scout. Finally, he said:

“I hardly know where to begin. Pretty near all these stories are true. I was at it all the war. That affair of my swimming the river took place on that long scout of mine when I was with the rebels five months when I was sent by General Curtis to Price’s army. Things had come pretty close at that time, and it wasn’t safe to go straight inter their lines. Everybody was suspected who came from these parts. So I started off and went way up to Kansas City. I bought a horse there and struck out onto the plains, and then went down through Southern Kansas into Arkansas. I knew a rebel named Barnes, who was killed at Pea Ridge. He was from near Austin in Texas. So I called myself his brother and enlisted in a regiment of mounted rangers.”

“General Price was just then getting ready for a raid into Missouri. It was sometime before we got into the campaign, and it was mighty hard work for me. The men of our regiment were awful. They didn’t mind killing a man no more than a hog. The officers had no command over them. They were afraid of their own men, and let them do what they liked; so they would rob and sometimes murder their own people. It was right hard for me to keep up with them, and not do as they did. I never let on that I was a good shot. I kept that back for big occasions; but ef you’d heard me swear and cuss the blue-bellies, you’d a-thought me one of the wickedest of the whole crew. So it went on until we came near Curtis’s army. Bime-by they were on one side of the Sandy River and we were on t’other. All the time I had been getting information until I knew every regiment and its strength; how much cavalry there was, and how many guns the artillery had. ”

“You see ‘twas time for me to go, but it wasn’t easy to git out, for the river was close picketed on both sides. One day when I was on picket our men and the rebels got talking and cussin each other, as you know they used to do. After a while one of the Union men offered to exchange some coffee for tobacco. So we went out onto a little island which was neutral ground like. The minute I saw the other party, who belonged to the Missouri cavalry, we recognized each other. I was awful afraid they’d let on. So I blurted out:

’Now, Yanks, let’s see yer coffee — no burnt beans, mind yer but the genuine stuff. We know the real article if we is Texans .’”

“The boys kept mum, and we separated. Half an hour afterward General Curtis knew I was with the rebs. But how to git across the river was what stumped me. After that, when I was on picket, I didn’t trouble myself about being shot. I used to fire at our boys, and they’d bang away at me, each of us taking good care to shoot wide. But how to git over the river was the bother. At last, after thinking a heap about it, I concluded that I always did, that the boldest plan is the best and safest.”

“We had a big sergeant in our company who was alms a-braggin that could stump any regiment man. He swore he had killed more Yanks than any man in the army, and that he could do more daring things than any others. So one day, when he was talking loud, I took him up and offered to bet horse for a horse that I would ride out into the open and nearer to the Yankees than he. He tried to back out of this, but the men raised a row, calling him a funk, and a bragger, and all that; so he had to go. Well, we mounted our horses, but before we came within shootin’ distance of the Union soldiers, I made my horse kick and rear so they could see who I was. Then we rode slowly to the river bank, side by side.”

“There must have been ten thousand men watching us; for, besides the rebs who wouldn’t have cried about it if we had both been killed, our boys saw something was up, and without being seen thousands of them came down to the river. Their pickets kept firing at the sergeant, but whether or not they were afraid of putting a ball through me I don’t know, but nary a shot hit him. He was a plucky feller all the same, for the bullets zitted about in every direction.”

“Bime-by we got right close ter the river, when one of the Yankee soldiers yelled out, ‘Bully for Wild Bill’”

“Then the sergeant suspicioned me, for he turned on me and growled out, ‘By God, I believe yer a Yank!’ And he at first drew his revolver, but he was too late, for the minute he drew his pistol, I put a ball through him. I mightn’t have killed him if he hadn’t suspicioned me. I had to do it then.”

“As he rolled out of the saddle I took his horse by the bit, and dashed into the water as quick as I could. The minute I shot the sergeant our boys set up a tremendous shout and opened a smashing fire on the rebs who had commenced popping at me. But I had got into deep water, and had slipped off my horse over his back, and steered him for the opposite bank by holding onto his tail with one hand, while I held the bridle rein of the sergeant’s horse in the other hand. It was the hottest bath I ever took. Whew! For about two minutes how the bullets zitted and skipped on the water. I thought I was hit again and again, but the reb sharp-shooters were bothered by the splash we made, and in a little while our boys drove them to cover, and after some tumbling at the bank got into the brush with my two horses without a scratch.”

“It is a fact,” said the scout, while he caressed his long hair,” I felt sort of proud when the boys took me into camp, and General Curtis thanked me before a heap of generals.”

“But I never tried that thing over again, nor I didn’t go a scouting openly in Price’s army after that. They all knew me too well, and you see ‘twouldn’t be healthy to have been caught.”

The scout’s story of swimming the river ought, perhaps, to have satisfied my curiosity but I was especially desirous to hear him relate the history of a sanguinary fight which he had with a party of ruffians in the early part of the war, when, single-handed, he fought and killed ten men. I had heard the story as it came from an officer of the regular army who, an hour after the affair, saw Bill and the ten dead men, some killed with bullets, others hacked and slashed to death with a knife.

As I write out the details of this terrible tale from notes which I took as the words fell from the scout’s lips, I am conscious of its extreme improbability; but while I listened to him, I remembered the story in the Bible, where we are told that Samson with the jawbone of an ass slew a thousand men, and as I looked upon this magnificent example of human strength and daring, he appeared to me to realize the powers of a Samson and Hercules combined, and I should not have been inclined to place any limit on his achievements. Besides this, one who has lived for four years in the presence of such grand heroism and deeds of prowess as was seen during the war is in what might he called a receptive mood. Be the story true or not, in part or in whole, I believed then every word Wild Bill uttered, and I believe it today.

“I don’t like to talk about that McCanles affair,” said Bill in answer to my question.

“It gives me a queer shiver whenever I think of it, and sometimes I dream about it, and wake up in a cold sweat.”

“You see this McCanles was the Captain of a gang of desperadoes, horse thieves, murderers, regular cut-throats, who were the terror of everybody on the border, and who kept us in the mountains in hot water whenever they were around. I knew them all in the mountains where they pretended to be trapping, but they were there hiding from the hangman. McCanles was the biggest scoundrel and bully of them all and was allers a-braggin of what he could do. One day I beat him shootin at a mark, and then threw him at the back-bolt. And I didn’t drop him as soft as you would a baby, you may be sure. Well, he got savage mad about it, and swore he would have his revenge on me some time.”

“This was just before the war broke out, and we were already takin sides in the mountains either for the South or the Union. McCanles and his gang were border-ruffians in the Kansas row, and of course, they went with the rebs. Bime-by he clar’d out, and I shouldn’t have thought of the feller agin ef he hadn’t crossed my path. It ‘pears he didn’t forget me.”

“It was in ‘61 when I guided a detachment of cavalry who were commin from Camp Floyd. We had nearly reached the Kansas line, and were in South Nebraska, when one afternoon I went out of camp to go to the cabin of an old friend of mine, a Mrs. Wellman. I took only one of my revolvers with me, for although the war had broke out I didn’t think it necessary to carry both my pistols, and, in all or’nary scrimmages, one is better than a dozen, if you shoot straight. I saw some wild turkeys on the road as I was goin down, and popped one of ‘em over, thinking he’d he just the thing for supper.”

“Well, I rode up to Mrs. Wellman, jumped off my horse, and went into the cabin, which is like most of the cabins on the prarer, with only one room, and that had two doors, one opening in front and t’other on a yard, like.”

“How are you, Mrs. Wellman?” I said, feeling as jolly as you please.

“The minute she saw me she turned as white is a sheet and screamed: ‘Is that you, Bill? Oh, my God! They will kill you! Run! Run! They will kill you!’”

“Whos a-goin to kill me?” I said. “There’s two can play at that game.”

“’It’s McCanles and his gang. There’s ten of them, and you’ve no chance. They’ve jes gone down the road to the corn-rack. They came up here only five minutes ago. McCanles was draggin poor Parson Shipley on the ground with a lariat round his neck. The preacher was most dead with choking and the horses stamping on him. McCanles knows yer bringin in that party of Yankee cavalry, and he swears he’ll cut yer heart out. Run, Bill, run! But it’s too late; they’re commin up the lane’”

“While she was a-talkin I remembered I had but one revolver, and a load gone out of that. On the table there was a horn of powder and some little bars of lead. I poured some powder into the empty chamber and rammed the lead after it by hammering the barrel on the table, and had just capped the pistol when I heard McCanles shout: ‘There’s that d—d Yank Wild Bill’shorse; he’s here; and we’ll skin him alive!’”

“If I had thought of runnin before, it war too late now, and the house was my best holt –a sort of fortress, like. I never thought I should leave that room alive.”

The scout stopped in his story, rose from his seat, and strode back and forward in a state of great excitement.

“I tell you what it is, Kernel,” he resumed, after a while, “I don’t mind a scrimmage with these fellers round here. Shoot one or two of them and the rest run away. But all of McCanles’ Gang were reckless, blood-thirsty devils, who would fight as long as they had strength to pull a trigger. I have been in tight places, but that’s one of the few times I said my prayers.”

“Surround the house and give him no quarter!’ yelled McCanles. When I heard that I felt as quiet and cool as if I was a-goin to church. I looked round the room and saw a Hawkins rifle hangin over the bed.”

“Is that loaded?” I said to Mrs. Wellman.

“’Yes,’ the poor thing whispered. She was so frightened she couldn’t speak out loud.”

“’Are you sure?’ I said, as I jumped to the bed and caught it from its hooks. Although my eyes did not leave the door, I could see she nodded Yes again. I put the revolver on the bed, and just then, McCanles poked his head inside the doorway but jumped back when he saw me with the rifle in my hand.”

“’Come in here, you cowardly dog! I shouted. Come in here and fight me!’

“McCanles was no coward if he was a bully. He jumped inside the room with his gun leveled to shoot, but he was not quick enough. My rifle-ball went through his heart. He fell back outside the house, where he was found afterward holding tight to his rifle, which had fallen over his head.”

“A yell from his gang followed his disappearance, and then there was a dead silence. I put down the rifle and took the revolver, and I said to myself: ‘Only six shots and nine men to kill. Save your powder, Bill, for the death-hugs a-comin!’ I don’t know why it was, Kernel,” continued Bill, looking at me inquiringly, “but at that moment things seemed clear and sharp. I could think strong.”

“There was a few seconds of that awful stillness, and then the ruffians came rushing in at both doors. How wild they looked with their red, drunken faces and inflamed eyes, shouting and cussin! But I never aimed more deliberately in my life.”

“One—two—three—four; and four men fell dead.”

“That didn’t stop the rest. Two of them fired their bird guns at me. And then I felt a sting run all over me. The room was full of smoke. Two got in close to me, their eyes glaring out of the clouds. One I knocked down with my fist. “you are out of the way for a while,” I thought. The second I was shot dead. The other three clutched me and crowded me onto the bed. I fought hard. I broke with my hand one man’s arm. He had his fingers round my throat. Before I could get to my feet, I was struck across the breast with the stock of a rifle, and I felt the blood rushing out of my nose and mouth. Then I got ugly, and I remember that I got hold of a knife, and then it was all cloudy-like, and I was wild, and I struck savage blows, following the devils up from one side to the other of the room and into the corners, striking and slashing until I knew that everyone was dead.”

“All of a sudden it seemed as if my heart was on fire. I was bleeding everywhere. I rushed out to the well and drank from the bucket, and then tumbled down in faint.”

Breathless with the intense interest with which I had followed this strange story, all the more thrilling and weird when its hero, seemingly to live over again the bloody events of that day, gave way to its terrible spirit with wild, gestures. I saw then – what my scrutiny of the morning had failed to discover – the tiger that lay concealed beneath that gentle exterior.

“You must have been hurt almost to death,” I said.

“There were eleven buck-shot in me. I carry some of them now. I was cut in 13 places. All of them bad enough to have let out the life of a man. But that blessed old Dr. Mills pulled me safe through it, after a bed siege of many a long week.”

“That prayer of yours, Bill, may have been more potent for your safety than you think. You should thank God for your deliverance.”

“To tell you the truth, Kernel,” responded the scout with a certain solemnity in his grave face, “I don’t talk about sich things ter the people round here, but I allers fell sort of thankful when I get out of a bad scrape.”

“In all your wild, perilous adventures,” I asked him, “have you ever been afraid? Do you know what the sensation is? I am sure you will not misunderstand the question, for I take it we soldiers comprehend justly that there is no higher courage than that which shows itself when the consciousness of danger is keen but where moral strength overcomes the weakness of the body.”

“I think I know what you mean, Sir, and I’m not ashamed to say that I have been so frightened that it appeared as if all the strength and blood had gone out of my body, and my face was as white as chalk. It was at the Wilme Creek fight. I had fired more than 50 cartridges, and I think fetched my man every time. I was on the skirmish line and was working up closer to the rebs when all of a sudden a battery opened fire right in front of me, and it sounded as if 40,000 guns were firing, and ever shot and shell screeched within six inches of my head. It was the first time I was ever under artillery fire, and I was so frightened that I couldn’t move for a minute or so. When I did go back, the boys asked me if I had seen a ghost. They may shoot bullets at me by the dozen, and it’s rather exciting if I can shoot back, but I am always nervous when the big guns go off.”

“I would like to see you shoot.”

“Would yer?” replied the scout, drawing his revolver, approaching the window, he pointed to a letter O in a signboard fixed to the stone wall of a building on the other side of the way.

“That sign is more than 50 yards away. I will put these six balls inside the circle, which isn’t bigger than a man’s heart.”

In an off-hand way, and without sighting the pistol with his eye, he discharged the six shots of his revolver. I afterward saw that all the bullets had entered the circle.

As Bill proceeded to reload his pistol, he said to me with a naiveté of manner which was meant to he assuring:

“Whenever you get into a row be sure and not shoot too quick. Take time. I’ve known many a feller slip up for shooting in a hurry.”

It would be easy to fill a volume with the adventures of that remarkable man. My object here has been to make a slight record of one of the best – perhaps the very best – example of a class who, more than any other, encountered perils and privations in defense of our nationality.

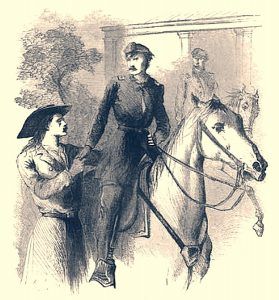

One afternoon as General Smith and I mounted our horses to start upon our journey toward the East, Wild Bill came to shake hands goodbye, and I said to him:

“If you have no objection I will write an account of a few of your adventures for publication.”

“Certainly you may,” he replied. “I’m sort of public property. But., Kernel,” he continued, leaning upon my saddle bow, while there was a tremulous softness in his voice and a strange moisture in his averted eyes, “I have a mother back there in Illinois who is old and feeble. I haven’t seen her this many a year, and haven’t been a good son to her, yet I love her better than anything in this life. It don’t matter much what they say about me here. But I’m not a cut-throat and vagabond, and I’d like the old woman to know what’ll make her proud. I’d like her to hear that her runaway boy has fought through the war for the Union like a true man.”

William Hickok called Wild Bill, the Scout of the Plains shall have his wish. I have told his story precisely as it was told to me, confirmed in all important points by many witnesses, and I have no doubt of its truth.

— G.W.N.

To see the original article, visit the Cornell University Library.

About the Article and the Author:

Hickok bids farewell to George Ward Nichols, illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

This article, written by George Ward Nichols, was excerpted, in part, from an article that appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, entitled Wild Bill, in February 1867, now in the public domain. The article is not verbatim, as glaring errors, such as Nichols referring to Bill Hickok as William Hitchcock, and other grammatical and spelling corrections have been made. Additionally, the material that appears has been truncated.

George Ward Nichols worked as a journalist until the outbreak of the Civil War when he joined the Union Army, where he served on the staff of Generals John C. Fremont and William Sherman. Before he was released from service, he rose to lieutenant colonel. After the war, he published several stories in various publications, including the article that appears here.

Newspapers such as the Leavenworth Daily Conservative, Kansas Daily Commonwealth, Springfield Patriot, and the Atchison Daily Champion quickly pointed out that the article was full of inaccuracies and that Hickok was lying when he claimed he had killed “hundreds of men.” After these heavy attacks, he concentrated on writing about music and became the Cincinnati College of Music president. Books by Nichols include Art Education Applied to Industry in 1877 and Pottery in 1878. He died on September 15, 1885.

Criticisms of George Ward Nichol’s Article “Wild Bill”

In February 1867, an article entitled Wild Bill appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Written by George Ward Nichols, the tale wildly exaggerated Bill Hickok’s deeds, defamed the people of Springfield, Missouri, and included numerous downright inaccuracies.

Response to the Nichols article was heavily attacked by the press, so much so, that Nichols soon turned away from this type of journalism and concentrated on writing about other things.

Even though the article was inaccurate and widely thought of as being little more than entertainment fodder for those in the East, it was still widely read and largely perpetuated Bill Hickok’s already-growing legend.

Listed below are some of the excerpts regarding the article:

From the Leavenworth Daily Conservative on January 30, 1867

From the Leavenworth Daily Conservative on January 30, 1867

The story of “Wild Bill,” as told in Harper’s for February, is not easily credited hereabouts. To those of us who were engaged in the campaign, it sounds mythical, and whether Harry York, Buckskin Joe, or Ben Nugget is meant in the life sketches of Harper, we are not prepared to say. The scout services were so mixed that we are unable to give precedence to any. “Wild Bill’s” exploits at Springfield have not yet been heard of here, and if such brave deeds occurred under that cognomen, we have not been given the relation. There are many of the rough riders of the rebellion now in this city whose record would compare very favorably with that of “Wild Bill,” if another account is wanted, we might refer to Walt Sinclair.

From the Springfield Patriot on January 31, 1867

Springfield is excited. It has been so ever since the mail of the 25th brought Harper’s Monthly to its numerous subscribers here. Curiously, the excitement manifests itself in very opposite effects upon our citizens. Some are excessively indignant, but most are in convulsions of laughter, which seem interminable. The cause of both abnormal moods in our usually placid and quiet city is the first article in Harper for February, which all agree, if published at all, should have had its place in the “Editor’s Drawer,” with the other fabricated more or less funnyisms; and not where it is, in the leading “illustrated” place. But, upon reflection, as Harper has given the same prominence to “Heroic Deeds of Heroic Men,” by Rev. J. T. Headley, which, generally, are of about the same character as its article “Wild Bill,” we will not question the good taste of its “makeup.”

We are importuned by the angry ones to review it. “For,” say they, “it slanders our city and citizens so outrageously by its caricatures that it will deter some from immigrating here, who believe its representations of our people.”

“Are there any so ignorant?” we asked.

“Plenty of them in New England, and especially about the Hub, just as ready to swallow it all as Gospel truth as a Johnny Chinaman or Japanese would be to believe that cannibals inhabit England, France, and America.”

“Don’t touch it,” cries the hilarious party, “don’t spoil a richer morceaux than ever was printed in Gulliver’s Travels or Baron Munchausen! If it prevents any consummate fools from coming to Southwest Missouri, that’s no loss.”

So we compromise between the two demands and give the article but brief and inadequate criticism. Indeed, we do not imagine we could do it justice if we made it so serious and studied an attempt to do so.

A good many of our people – those especially who frequent the barrooms and lager-beer saloons, will remember the author of the article when we mention one “Colonel” G. W. Nichols, who was here for a few days in the summer of 1865, splurging around among our “strange, half-civilized people,” seriously endangering the supply of lager and corn whisky, and putting on more airs than a spotted stud-horse in the ring of a county fair. He’s the author!

And if the illustrious holder of one of the “Brevet” commissions which Fremont issued to his wagon masters, will come back to Springfield, two-thirds of all the people he meets will invite him “to pis’n hisself with suth’n” for the fun he unwittingly furnished them in his article – the remaining one-third will kick him wherever met, for lying like a dog upon the city and people of Springfield.

James B Hickok (not “William Hitchcock,” as the “Colonel” misnames his hero) is a remarkable man and is as well known here as Horace Greeley in New York or Henry Wilson in “The Hub.” The portrait of him on the first page of Harper for February is a most faithful and striking likeness – features, shape, posture, and dress – in all, it is a faithful reproduction of one of Charley Scholten’s photographs of “Wild Bill,” as he is generally called. No finer physique, no greater strength, no more personal courage, no steadier nerves, no superior skill with the pistol, no better horsemanship than his, could any man of the million Federal soldiers of the war boast of, and few did better or more loyal service as a soldier throughout the war. But Nichols “cuts it very fat” when he describes Bill’s teats in arms. We think his hero only claims to have sent a few dozen rebs to the farther side of Jordan, and we never, before reading the “Colonel’s” article, suspected he had dispatched “several hundred with his own hands.” But it must be so, for the “Colonel” asserts it with a parenthesis of genuine flavorous Bostonian piety to assure us of his incapacity to utter an untruth.

From the Atchison Daily Champion on February 5, 1867

‘Wild Bill” is, as stated in the Magazine, a splendid specimen of physical manhood and is a dead shot with a pistol. He is very quiet, rarely talking to anyone, and not of a quarrelsome disposition, although reckless and desperate when once involved in a fight. Several citizens of this city know him well.

Nichols’ sketch of ‘Wild Bill’ is a very readable paper, but the fine descriptive powers of the writer have been drawn upon as primarily as facts in producing it. There are dozens of men on the Overland Line who are probably more desperate characters than Hickok and are the heroes of quite as many and as desperate adventures. The Wild West is fertile in ‘Wild Bill’s.’ Charley Slade, formerly one of the division Superintendents on the O. S. Line, was probably a more desperate, as well as a cooler man than the hero of Harper’s, and his fight at his ranch was a much more terrible encounter than that of ‘Wild Bill with the McKandles gang.

From the Kansas Daily Commonwealth on May 11, 1873

It is disgusting to see the Eastern papers crowding in everything they can get hold of about “Wild Bill.” If they only knew the real character of the men they wanted to worship, we doubt if their names would ever reappear. “Wild Bill,” or Bill Hickok, is nothing more than a drunken, reckless, murderous coward who is treated with contempt by true border men and who should have been hung years ago for the murder of innocent men. The shooting of the “old teamster” in the back for a small provocation while crossing the plains in 1859 is one fact that Harper’s correspondent failed to mention, and being booted out of a Leavenworth saloon by a boy bartender is another, and we might name many other similar examples of his bravery. In one or two instances, he did the U. S. government good service, but his shameful and cowardly conduct more than overbalances the good.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025.

Also See:

McCanles Massacre – A WPA Interview

Rock Creek Station & the McCanles Massacre