by William MacLeod Raine, 1925.

It was in the days when the new railroad was pushing through the country of the Plains Indians that a drunken cowboy got on the train at a way station in Kansas. John Bender, the conductor, asked him for his ticket. He had none, but he pulled out a handful of gold pieces.

“I wantta–g-go to–h-hell,” he hiccoughed.

Bender did not hesitate an instant. “Get off at Dodge. One dollar, please.”

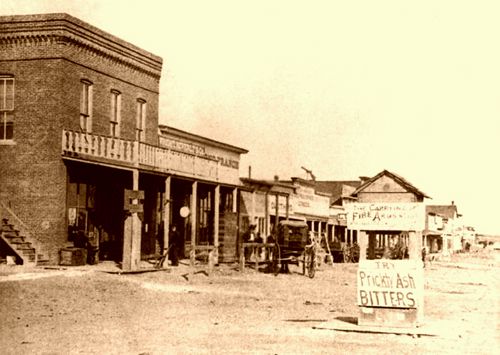

Dodge City was laid out by A.A. Robinson, chief engineer of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. It was named for Colonel Richard I. Dodge, commander of the post at Fort Dodge and one of the place’s founders.

Dodge was a wild and uncurried prairie wolf that howled every night and all night. It was gay and young and lawless. Its sense of humor was exaggerated and worked overtime. The crack of the six-shooter punctuated its hilarity ominously. Those who dwelt there were the brave vanguard of civilization. For good or bad, they were strong and forceful, and many of them were generous and big-hearted despite their lurid lives. The town was a hive of energy. One might justly use many adjectives about it, but the word respectable is not among them.

There were three reasons why Dodge won the reputation of being the wildest town the country had ever seen. In 1872 it was the end of the track, the last jumping-off spot into the wilderness, and in the days when transcontinental railroads were built across the desert, the temporary terminus was always a gathering place of roughs and scalawags. The payroll was large, and gamblers, gunmen, and thugs gathered for the pickings. This was true of Hays, Abilene, Ogallala, and Kit Carson. It was true of Las Vegas and Albuquerque, New Mexico.

A second reason was that Dodge was the end of the long trail drive from Texas. Every year, hundreds of thousands of longhorns were driven up from Texas by cowboys, who were scarcely less wild than the hill steers they herded. The Great Plains country was being opened, and cattle were needed to stock a thousand ranches and supply the government at Indian reservations. Scores of these trail herds were brought to Dodge for shipment, and after the long, dangerous drive, the punchers were keen to spend their money on such diversions as the town could offer. Out of sheer high spirits, they liked to shoot up the town, to buck the tiger, to swagger from saloon to gambling hall, their persons garnished with revolvers, the spurs on their high-heeled boots jingling. In no spirit of malice, they wanted it distinctly understood that they owned the town. As one of them once put it, he was born high up on the Guadeloupe River, raised on prickly pear, had palled with alligators, and quarreled with grizzlies.

Also, Dodge was the heart of the buffalo country. Here, the hunters were outfitted for the chase. From here, great quantities of hides were shipped back to the new railroad. Robert M. Wright, one of the town’s founders and always one of its leading citizens, says that his firm alone shipped 200,000 hides in one season.

He estimates the number of buffalo in the country to be more than twenty-five million, admitting that many are as well-informed as he is. Put the figure at four times as many. Many times, he and others traveled through the vast herds for days at a time without ever losing sight of them.

The killing of buffalo was easy because the animals were so stupid. When one was shot, they would mill around and around. Tom Nixon killed 120 in 40 minutes; in a little more than a month, he slaughtered 2,173 of them. With good luck, a man could earn $100 a day. If he had bad luck, he lost his scalp.

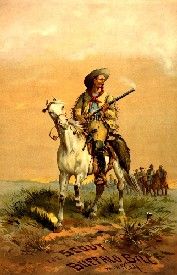

The buffalo was to the Plains Indians food, fuel, and shelter. As long as there were plenty of buffalo, he was in Paradise. But he saw at once that this slaughter would soon exterminate the supply. He hated the hunter and battled against his encroachments. The buffalo hunter was an intrepid plainsman. He fought Kiowa, Comanche, the Staked Plains Apache, the Sioux, and the Arapaho. Famous among these hunters were Kirk Jordan, Charles Rath, Emanuel Dubbs, Jack Bridges, and Curly Walker. Others, even better known, were the two Buffalo Bills (William Cody and William Mathewson) and Wild Bill Hickok.

These three factors then made Dodge the end of the railroad, the terminus of the cattle trail from Texas, and the center of the buffalo trade. Together, they made it “the beautiful bibulous Babylon of the frontier,” according to the editor of the Kingsley Graphic. There was to come a time later when the bibulous Babylon fell on evil days, and its primary source of income was old bones. They were buffalo bones, gathered in wagons and piled beside the track for shipment, hundreds and hundreds of carloads of them, to be used for fertilizer. (I have seen significant quantities of such bones as far north as the Canadian Pacific line, corded for shipment to a factory.) It used to be said by way of derision that buffalo bones were legal tender in Dodge.

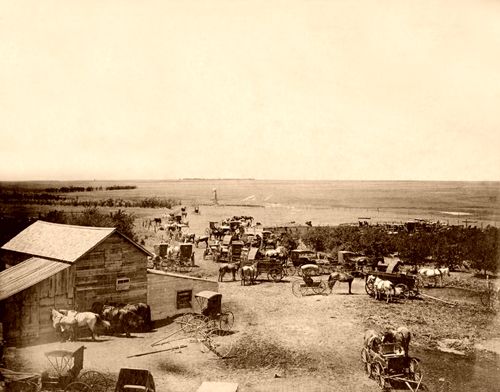

But that was in the far future. In its early years, Dodge rode the wave of prosperity. Hays, Abilene, and Ogallala had their day, but Dodge had its day and its night, too. For years, it did a tremendous business. The streets were so blocked that one could hardly get through. Hundreds of wagons and outfits belonging to freighters, hunters, cattlemen, and the government were parked there. Scores of camps surrounded the town in every direction. The yell of the cowboy, the weird oath of the bullwhacker, and the muleskinner were heard in the land. And for a time, there was no law nearer than Hays City, which was itself a burg not given to undue peace and quiet.

Dodge was no sleepy village that could drowse along without peace officers. Bob Wright has set it down that in the first year of its history, 25 men were killed and twice as many wounded. The elements that made up the town were too diverse for perfect harmony.

The freighters did not like the railroad graders. The soldiers at the fort fancied themselves as scrappers. The cowboys and the buffalo hunters did not mingle a little bit. The result was that Boot Hill began to fill up. Its inhabitants were buried with their boots on and without coffins.

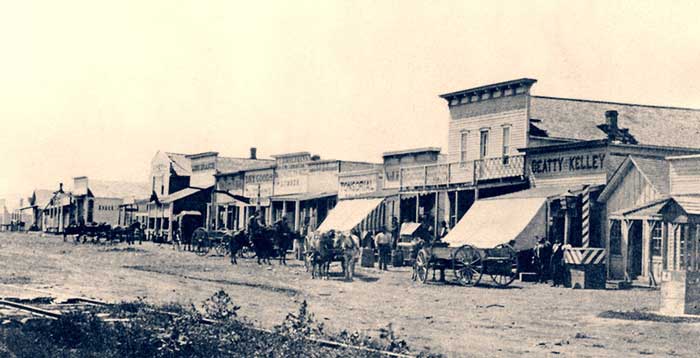

Dodge City Gathering.

There was another cemetery for those who died in their beds. The climate was so healthy that it would have been sparsely occupied those first years if it had not been for the skunks. During the early months, Dodge was a city of camps. The fires flamed up from the vicinity of hundreds of wagons every night. Skunks were numerous. They crawled at night into the warm blankets of the sleepers and bit the rightful owners when they protested. A dozen men died from these bites. It was thought at first that the animals were a special variety known as the hydrophobic skunk. In later years, I have sat around Arizona campfires and heard this subject heatedly discussed. The Smithsonian Institute appealed as the referee decided that there was no such species and that deaths from the bites of skunks were probably due to blood poisoning caused by the foul teeth of the animal.

Judging by comparative statistics, the skunks were only half as venomous as the gunmen. Dodge decided it had to have the law in the community. Jack Bridges was appointed the first marshal.

Jack was a noted scout and buffalo hunter who would have peace if he had to fight for it. He slept in the afternoon since this was the quiet time of the day. One day, someone shook him out of slumber to tell him that cowboys were riding up and down Front Street, shooting the windows out of buildings. Jack sallied out, old buffalo gun in hand. The cowboys went whooping down the street across the bridge toward their camp. The old hunter took a long shot at one of them and dropped him. The cowboys buried the young fellow the next day.

There was a good deal of excitement in the cow camps. If the boys could not have a little fun without some old donker, an old vinegaroon who couldn’t take a joke, filling them full of lead, it was a pretty howdy-do. But Dodge stood pat. The coroner’s jury voted it justifiable homicide. In the future, the young Texans were more discreet. In the early days, whatever law there was did not interfere with casualties due to personal differences of opinion, provided the affair had no unusually sinister aspect.

The first wholesale killing was at Tom Sherman’s dance hall. The affair was between soldiers and gamblers. It was started by a trooper named Hennessey, who had a reputation as a bad man and a bully. He was killed, as were several others. The officers at the fort glossed over the matter, perhaps because they felt the soldiers had been to blame.

One of the lawless characters who drifted into Dodge the first year was Billy Brooks. He quickly established a reputation as a killer. My old friend Emanuel Dubbs, a buffalo hunter who “took the hides off’n” many a bison, is the authority for the statement that Brooks killed or wounded 15 men in less than a month after his arrival. Now Emanuel is a preacher (if he is still in the land of the living; I saw him last at Clarendon, Texas, ten years or so ago), but I cannot quite swallow that “fifteen.” Still, he had a man for breakfast now and then and, on one occasion, four.

Brooks, by the way, was the assistant marshal. It was the policy of the officials of these wild frontier towns to elect as marshal some conspicuous killer, on the theory that desperadoes would respect his prowess or, if they did not, would get the worst of the encounter.

Abilene, for instance, chose “Wild Bill” Hickok. Austin had its Ben Thompson. According to Bat Masterson, Thompson was the most dangerous man with a gun among all the bad men he knew — and Bat knew them all. Ben was an Englishman who struck Texas while still young. He fought as a Confederate under Kirby Smith during the Civil War and under Shelby for Maximilian. Later, he became a city marshal in Austin. Thompson was a man of the coolest effrontery. On one occasion, during a cattlemen’s convention, a banquet was held at the leading hotel. The local congressman, a friend of Thompson, was not invited. Ben took exception to this and attended in person. By way of pleasantry, he shot the plates in front of the diners. Later, one of those present made a humorous comment. “I always thought Ben was a game man. But what did he do? Did he hold up the whole convention of a thousand cattlemen? No, sir. He waited until he got 40 or 50 poor fellows alone before he turned loose his wolf.”

Of all the evil men and desperadoes produced by Texas, not one of them, not even John Wesley Hardin himself, was more feared than Ben Thompson. Sheriffs avoided serving warrants of arrest on him. It is recorded that when the county court was in session with a charge against him on the docket, Thompson rode into the room on a Mustang. He bowed pleasantly to the judge and court officials.

“Here I am, gents, and I’ll lay all I’m worth that there’s no charge against me. Am I right? Speak up, gents. I’m a little deaf.”

There was a dead silence until, at last, the court clerk murmured, “No charge.”

A story is told that on one occasion, Ben Thompson met his match in the form of a young English remittance man playing cards with him. The remittance man thought he caught Thompson cheating and indiscreetly said so. Instantly, Thompson’s .44 covered him. The gambler gave the lad a chance to retract for some unknown reason.

“Take it back–and quick,” he said grimly.

Every game in the house was suspended while all eyes turned on the dare-devil boy and the hard-faced desperado. The remittance man went white, half rose from his seat, and shoved his head across the table toward the revolver.

“Shoot and be damned. I say you cheat,” he cried hoarsely.

Thompson hesitated, laughed, shoved the revolver back into its holster, and ordered the youngster out of the house.

Perhaps the most amazing escape on record is that when Thompson, fired at by Mark Wilson at a distance of ten feet from a double-barreled shotgun loaded with buckshot, whirled instantly, killed him, and an instant later shot through the forehead, Wilson’s friend, Mathews. However, the latter had ducked behind the bar to get away. The second shot was guesswork, plus quick thinking and accurate aim. Ben was killed a little later, in company with his friend King Fisher, another bad man, at the Palace Theatre. A score of shots were poured into them by a dozen men waiting in ambush. Both men had become so dangerous that their enemies could not afford to let them live.

King Fisher was the humorous gentleman who put up a signboard at the fork of a public road bearing the legend:

THIS IS KING FISHER’S ROAD.

TAKE THE OTHER

It is said that those traveling that way followed his advice. The other road might be a mile or two farther, but they were in no hurry. Another amusing little episode in King Fisher’s career is told. He had had some slight difficulty with a certain bald man. Fisher shot him and carelessly gave the reason that he wanted to see whether a bullet would glance from a shiny pate.

El Paso, in its wild days, chose Dallas Stoudenmire for marshal, and after he had been killed, John Selman. Both of them were noted killers. During Selman’s régime, John Wesley Hardin came to town. Hardin had 27 notches on his gun and was the worst man-killer Texas had ever produced. He was at the bar of a saloon, shaking dice, when Selman shot him from behind. One year later, Deputy United States Marshal George Scarborough killed Selman in a duel. Shortly after this, Scarborough was slain in a gunfight by “Kid” Curry, an Arizona bandit.

What was true of these towns was also true of Albuquerque, Las Vegas, and Tombstone. Each of them chose for peace officers men who were “sudden death” with a gun.

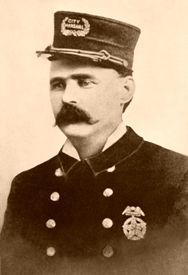

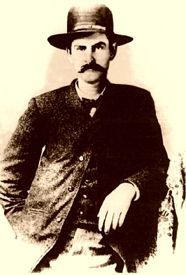

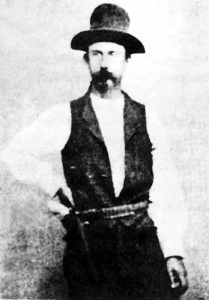

Dodge did the same thing. Even a partial list of its successive marshals reads like a fighting roster. In addition to Bridges and Brooks may be named Ed and Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp, Billy Tilghman, Ben Daniels, Mysterious Dave Mathers, T.C. Nixon, Luke Short, Charley Bassett, W.H. Harris, and the Sughrue brothers, all of them famous as fighters in a day when courage and proficiency with weapons were a matter of course. On one occasion, the superintendent of Santa Fe suggested to the city dads of Dodge that it might be a good thing to employ less notorious marshals. Dodge begged to leave to differ. It felt that the best way to “settle the hash” of desperadoes was to pit against them, fighting machines that were more efficient and evil men who were more deadly than themselves.

The word “bad” does not necessarily imply evil. One who held the epithet was known as one dangerous to oppose. He was unafraid, deadly with a gun, and hard as nails. He might be as evil, callous, treacherous, and revengeful as an Apache. Dave Mathers fitted this description. He might be a good man, kind and gentle, never taking more than his fighting chance. This was Billy Tilghman to a T.

We are keeping Billy Brooks waiting. But let that go. Let us look first at “Mysterious Dave.” Bob Wright has noted that Mathers had more dead men to his credit than any other man in the West. He slew seven by actual count in one night, in one house, according to Wright. Mathers had a terrible reputation. But his courage could blaze up magnificently. While he was deputy marshal, word came that the Henry gang of desperadoes was terrorizing a dance hall. Into that hall walked Dave, beside his chief, Tom Carson. Five minutes later, out-reeled Carson, both arms broken, his body shot through and through, a man with only minutes to live. When the smoke in the hall cleared away, Mathers might have been seen beside two handcuffed prisoners, one of them wounded. In a circle around him were four dead cowpunchers of the Henry outfit.

“Uncle” Billy Tilghman died the other day at Cromwell, Oklahoma, a victim of his own fearlessness. He was shot to death while taking a revolver from a drunken prohibition agent. He would have shot the fellow down at the first sign of danger if he had been like many other bad men.

But that was never Tilghman’s way. It was his habit to make arrests without drawing a gun. He cleaned up Dodge during the three years while he was marshal. He broke up the Doolin gang, killing Bill Raidler and “Little” Dick in personal duels and capturing Bill Doolin, the leader. Bat Masterson said that during Tilghman’s terms as sheriff of Lincoln County, Oklahoma, he killed, captured, or drove from the country more criminals than any other official that section ever had. Yet “Uncle” Billy never used a gun except reluctantly. Time and again, he gave the criminal the first shot, hoping the man would surrender rather than fight. None of the old frontier sheriffs holds a higher place than Billy Tilghman.

After which diversion, we return to Billy Brooks, a “gent” of an impatient temperament, not used to waiting, and notably quick on the trigger. Mr. Dubbs records that late one evening in the winter of 1872-’73, he returned to Dodge with two loads of buffalo meat. He finished his business, ate supper, and started to smoke a postprandial pipe. The sound of a fusillade in an adjoining dance hall interested him since he had been deprived of the pleasures of metropolitan life for some time and had had to depend upon Indians for excitement. (Incidentally, it may be mentioned that they furnished him a reasonable amount. Not long after this, three of his men were caught, spread-eagled, and tortured by Indians. Dubbs escaped after a hair-raising ride and arrived at Adobe Walls in time to take part in the historic defense of that post by a handful of buffalo hunters against many hundreds of tribesmen.) From the building burst four men. They started across the railroad track to another dance hall frequented by Brooks. Dubbs heard the men mention the name of Brooks, coupling it with an oath. Another buffalo hunter named Fred Singer joined Dubbs. They followed the strangers, and just before the four reached the dance hall, Singer shouted a warning to the marshal. This annoyed the unknown four, and they promptly exchanged shots with the buffalo hunters. What then took place was startling in the sudden drama of it.

Billy Brooks stood in bold relief in the doorway, a revolver in each hand. He fired so fast that Dubbs says the sound was like a company discharging weapons. When the smoke cleared, Brooks still stood in the same place. Two of the strangers were dead, and two were mortally wounded. They were brothers. They had come from Hays City to avenge the death of a fifth brother shot down by Brooks sometime before.

Mr. Brooks had a fondness for the fair sex. He and Browney, the yardmaster, took a fancy to the same girl. Captain Drew was called, and she preferred Browney. Whereupon Brooks naturally shot him in the head. Perversely, to the surprise of everybody, Browney recovered and was soon back at his old job.

Brooks seems to have held no grudge against him for making light of his marksmanship in this manner. At any rate, his next affair was with Kirk Jordan, the buffalo hunter.

This was a very different business. Jordan had been in a hundred tight holes. He had fought Indians time and again. Professional killers had no terror for him. He threw down his big buffalo gun on Brooks, and the latter took cover. Barrels of water had been placed along the principal streets for fire protection. These had saved several lives during shooting scrapes. Brooks ducked behind one, and the ball from Jordan’s gun plunged into it. The marshal dodged into a store, out of the rear door, and into a livery stable. He was hidden under a bed. Alas! for a prominent reputation gone glimmering. Mr. Brooks fled to the fort, took the train from the siding, and shook forever the dust of Dodge from his feet. Whether he departed, deponent sayeth not.

How do I explain this? I don’t. I record a fact. Many gunmen were at one time or another subject to these panics during which the yellow streak showed. Not all of them by any means, but a very considerable percentage. They swaggered boldly and killed recklessly. Then, one day, some quiet little man with a cold gray eye called the turn on them, after which they oozed out of the surrounding scenery.

Owen P. White gives it on the authority of Charlie Siringo that Bat Masterson sang small when Clay Allison of the Panhandle, he of the well-notched gun, drifted into Dodge and inquired for the city marshal. But the old-timers at Dodge do not bear this out. Bat was at the Adobe Walls fight, one of 14 men who stood off 500 Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa tribes. He scouted for General Nelson Miles. He was elected sheriff of Ford County, with headquarters at Dodge City, when only 22 years of age. It was a tough assignment, and Bat executed it to the satisfaction of all concerned except the element he cowed.

I never met Bat until his killing days were past. He was dealing faro at a gambling house in Denver when I, a young reporter, first had the pleasure of looking into his cold blue eyes. It was a notable fact that all the frontier bad men had eyes either gray or blue, often a faded blue, expressionless, hard as jade.

It is only fair to Bat to say that the old-timers of Dodge do not accept the Siringo point of view about what Wright said of him, saying that he was absolutely fearless and no trouble hunter. ” Bat is a gentleman by instinct, of pleasant manners, good address, and mild until aroused, and then, for God’s sake, look out. He is a leader of men, has much natural ability, and good, hard common sense. There is nothing low about him. He is high-toned and broad-minded, cool and brave.” I give this opinion for what it is worth.

In any case, he was a most efficient sheriff. Dave Rudabaugh, later associated with Billy the Kid in New Mexico, staged a train robbery at Kinsley, Kansas, a territory not in Bat’s jurisdiction. However, Bat set out in pursuit of a posse. A near-blizzard was sweeping the country. A bat was made for Lovell’s cattle camp on the chance that the bandits would be forced to take shelter there. It was a good guess. Rudabaugh’s outfit rode in, stiff and half-frozen, and Bat captured the robbers without firing a shot. This was one of many captures Bat made.

He had a deep sense of loyalty to his friends. On two separate occasions, he returned to Dodge after leaving the town to straighten out difficulties for his friends or avenge them. The first time was when Luke Short, who ran a gambling house in Dodge, had difficulty with Mayor Webster and his official family. Luke appears to have believed that the cards were stacked against him and that this trouble prevented him from shooting himself. He wired Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp to come to Dodge. They did, accompanied by another friend or two. The mayor made peace on terms dictated by Short.

Bat’s second return to Dodge was caused by a wire from his brother James, who ran a dance hall in partnership with a man named Peacock. Masterson wanted to discharge the bartender, Al Updegraff, a brother-in-law of the other partner. A serious difficulty loomed in the offing. Therefore, James called for help. Bat arrived at eleven, one sunny morning, another gunman at his heel. At three o’clock, he entrained for Tombstone, Arizona, with James beside him. The interval had been a busy one. On the way up from the station (always known then as the depot), the two men met Peacock and Updegraff. No amenities were exchanged. It was strictly business. Bullets began to sing at once. The men stood across the street from each other and emptied their weapons. Oddly enough, Updegraff was the only one wounded. This little matter attended to, Bat surrendered himself, was fined three dollars for carrying concealed weapons, and was released. He ate dinner, disposed of his brother’s interest in the saloon, and returned to the station.

Bat Masterson was a friend of Theodore Roosevelt, who was fond of admiring men with “guts,” such as Pat Garrett, Ben Daniels, and Billy Tilghman. Mr. Roosevelt offered Masterson a place as United States Marshal of Arizona.

The ex-sheriff declined it. “If I took it,” he explained, “inside of a year, I’d have to kill some fool boy who wanted to get a reputation by killing me.” The President then offered Bat a place as Deputy United States Marshal of New York, which was accepted. From that time, Masterson became a citizen of the Empire State. For 17 years, he worked on a newspaper there and died a few years later with a pen in his hand. The entire newspaper fraternity respected him.

Owing to the pleasant habit of the cowboys of shooting up the town, they were required, when entering the city limits, to hand over their weapons to the marshal. The guns were deposited at Wright & Beverly’s store in a rack built for the purpose, and receipts were given for them. Sometimes, 100 six-shooters would be there at once. These were never returned to their owners unless the cowboys were sober.

To be a marshal of one of these fighting frontier towns was no post to be sought for by a supple politician. The place called for a chilled iron nerve and an uncanny skill with the Colt. Tom Smith, one of the gamest men and best officers who ever wore a star on the frontier, was killed in the performance of his duty. Colonel Breckenridge says that Smith, marshal of Abilene before “Wild Bill,” was the gamiest man he ever knew. He was a powerful, athletic man who would arrest himself unarmed, the most desperate character. He once told Breckenridge that anyone could bring in a dead man, but it took a good officer to take lawbreakers while they were alive. In this, he differed from Hickok, who did not take chances. He brought his men in dead. Nixon, the assistant marshal at Dodge, was murdered by “Mysterious Dave” Mathers, who himself once held the same post. Ed Masterson, after displaying conspicuous courage many times, was mortally wounded on April 9, 1878, by two desperate men, Jack Wagner and Alf Walker, who were terrorizing Front Street. Bat reached the scene a few minutes later and heard the story. As soon as his brother had died, Bat went after the desperadoes, met them, and killed them both. The death of Ed Masterson shocked the town. Civic organizations passed resolutions of respect. All business houses were closed during the funeral, the largest ever held in Dodge. It is not on record that anybody regretted the demise of the marshal’s assassins.

Among those who came to Dodge each season to meet the Texas cattle drive were Ben and Bill Thompson, gamblers who ran a faro bank. Previously, they had been accustomed to going to Ellsworth, but that point was the terminus of the drive. Here, they had ruled with a high hand, killed the sheriff, and made their getaway safely. Bill got into a shooting affray at Ogallala. He was severely wounded and was carried to the hotel. It was announced openly that he would never leave town alive. Ben did not dare to go to Ogallala, for his record there had outlawed him. He came to Bat Masterson.

Bat knew Bill’s nurse and arranged a plan for the campaign. A sham battle was staged at the big dance hall, during the excitement of which Bat and the nurse carried the wounded man to the train, got him to a sleeper, and into a bed. Buffalo Bill met them the next day at North Platte. He had relays of teams stationed on the road, and he and Bat guarded the sick man during the long ride, bringing him safely to Dodge.

Emanuel Dubbs ran a roadhouse not far from Dodge about this time. One day, he was practicing with his six-shooter when a splendidly built young six-footer rode up to his place. The stranger watched him as he fired at the tin cans he had put on fence posts. The young fellow suggested throwing a couple of cans up in the air. Dubbs did so. Out flashed the stranger’s revolvers. There was a roar of exploding shots. Dubbs picked up the cans. Four shots had been fired. Two bullets had drilled through each can.

“Better not carry a six-shooter till you learn to shoot,” Bill Cody suggested as he put his guns back into their holsters. “You’ll be a living temptation to some bad man.” Buffalo Bill was on his way back to the North Platte River

Life at Dodge was not all tragic. The six-shooter roared in the land a good deal, but some very many citizens went quietly about their business and took no part in the town’s nightlife. It was entirely optional with the individual. The little city had legitimate theatres, hurdy-gurdy houses, and gambling dens. There was the Lady Gay, for instance, a popular vaudeville resort. There were well-attended churches. But Dodge boiled so with exuberant young life, often inflamed by bad liquor, that theatre and church were likely to be the scenes of unexpected explosions.

A drunken cowboy became annoyed at Eddie Foy. While the comedian was reciting “Kalamazoo in Michigan,” the puncher began bombarding the frail walls from outside with a .45 Colt revolver. Eddie made a swift strategic retreat. A deputy marshal was standing near the cowpuncher, astride a plunging horse. The deputy fired twice. The first shot missed. The second brought the rider down. He was dead before he hit the ground. The deputy apologized later for his marksmanship, but he explained, “The bronc sure was sunfishin’ plenty.”

The killing of Miss Dora Hand, a young actress of much promise, was regretted by everybody in Dodge. A young fellow named Kennedy, the son of a wealthy cattleman, shot her unintentionally while he was trying to murder James Kelly. He fled. A posse composed of Sheriff Masterson, William Tilghman, Wyatt Earp, and Charles Bassett took the trail. They captured the man after wounding him desperately. He was brought back to Dodge, recovered, and escaped. His pistol arm was useless, but he used the other well enough to slay several other victims before someone made an end of him.

Dodge’s gay good spirits were continually expressed in practical jokes. The wilder these were, the better pleased the town was. “Mysterious Dave” was the central figure in one. An evangelist was conducting a series of meetings. He made a powerful magnetic appeal; many were the hard characters who walked the sawdust trail. The preacher set his heart on converting Dave Mathers, the worst of bad men and a notorious scoffer. The meetings prospered. The church grew too small for the crowds and adjourned to a dance hall. Dave became interested. He went to hear Brother Johnson preach. He went a second time and a third. “He certainly preaches like the Watsons and goes for sin all spraddled out,” Dave conceded. Brother Johnson grew hopeful. It seemed possible that this brand could be snatched from the burning. He preached directly at Dave, and Dave buried his head in his hands and sobbed. The preacher said he was willing to die if he could convert this one vile sinner. The other deacons agreed that they, too, would not object to going straight to heaven with the knowledge that Dave had been saved.

“They were right excited an’ didn’t know straight up,” an old-timer explained. “Dave, he looked so whipped, his ears flopped. Finally, he rose and said, ‘I’ve got your company, friends. Now, while we’re all saved, I reckon we had better start straight for heaven. First off, the preacher, then the deacons, and me last.’ Then Dave whips out a whoppin’ big gun and starts shootin’. The preacher went right through a window an’ took it with him. He was sure in some hurry. The deacons hunted cover. It seemed like they were willing to postpone taking that through a ticket to heaven. After that, they never worried about Dave’s soul anymore.”

Many rustlers gathered around Dodge in those days. The most notorious of these was a gang of more than 30 under the leadership of Dutch Henry and Tom Owens, two of the most desperate outlaws ever known in Kansas. A posse was organized to run down this gang under the leadership of Dubbs, who had lost some of his stock. Before starting, the posse telephoned Hays City to organize a company to head off the rustlers. Twenty miles west of Hays, the posse overtook the rustlers. A bloody battle ensued, during which Owens and several other outlaws were killed, and Dutch Henry was wounded six times. Several of the posse were also shot. The story has a curious sequel. When Emanuel Dubbs was county judge of Wheeler County, Texas, many years later, Dutch Henry came to his house and stayed there several days. He was a thoroughly reformed man. Not many years ago, Dutch Henry died in Colorado. He was a man with many good qualities. Even in his outlaw days, he had many friends among the law-abiding citizens.

After the battle with the Henry-Owens Gang, rustlers operated much more quietly, but they did not cease stealing. One night, three men were hanged on a cottonwood on Saw Log Creek, ten or twelve miles from Dodge. One of these was a young man of a good family who had drifted into rustling and had been carried away by its excitement. Another of the three was Tom Owens’s son. To this day, the place is known as Horse Thief Canyon. During its years of prosperity, many eminent men visited Dodge, including Generals Sherman and Sheridan, President Hayes, and General Miles. Its reputation had extended far and wide. It was the wild and woolly cowboy capital of the Southwest, a place to quicken the blood of any man. Nearly all that gay, hard-riding company of cowpunchers, buffalo hunters, bad men, and pioneers have vanished into yesterday’s seven thousand years. But certainly, Dodge once had its day and its night of glory. No more rip-roaring town ever bucked the tiger.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025. Author and Notes: This article was written by William MacLeod Raine in 1925. Raine (1871-1954) was a newspaperman and author of several popular Western adventure novels in the early 20th century.

Also See:

Dodge City — A Wicked Little Town

Fort Dodge History and Hauntings