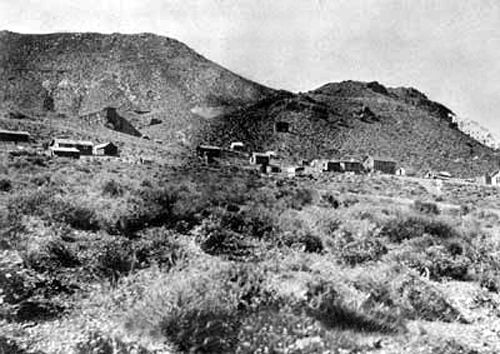

Gold Bar, Nevada.

The story of the Bullfrog Gold Bar Mining Company is not pleasing. However, it is all too typical of the mining history of the early 20th century. What started as a legitimate effort to exploit a high-grade gold deposit became a high-grade fraud.

The strikes at Tonopah and Goldfield attracted miners from all parts of the nation, and among them were two miners from Cripple Creek, Colorado, named Ben Hazeltine and N. P. Reinhart. Although they arrived in Goldfield too late to capitalize on that rush, they soon found jobs in local mines. By the time the news of Shorty Harris‘ and Ed Cross’ strike hit Goldfield, Reinhart, and Hazeltine were ready for another rush, and they joined the great migration to the new Bullfrog District.

Finding that all the close-in ground was already staked out, the two men drifted farther afield, prospecting in the upper Bullfrog Hills. In October, their persistence paid off, for they found and located the Hazeltine claims, approximately four miles northwest of Rhyolite and two miles north of the original Bullfrog.

The two men worked the mine alone for a short while and regularly brought in ore samples to be assayed at Rhyolite. The rich results of the assay tests did not go unnoticed, and early in 1905, Reinhart and Hazeltine sold their mine for $117,000 to Goldfield promoters, headed by J.P. Loftus and James R. Davis. The new company was soon organized as the Bullfrog Gold Bar Mining Company.

By the end of May 1905, after only six weeks of exploratory work, the mine had run into ore ledges averaging $15 per ton and had uncovered small, rich pockets, one of which assayed at $1,458 a ton. Ordering more equipment and hiring more men, the 14 miners continued to uncover evidence of paying ore. Towards the end of the summer, with the mine well into its development phase, a new boarding house had been completed for the convenience of the miners, and the Rhyolite Herald characterized the Gold Bar as “one of the surest and most dependable properties in the district.”

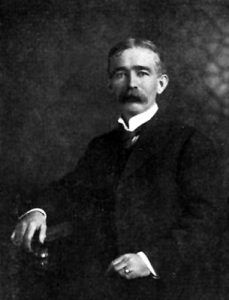

The good news continued through 1906, and by March, three shifts of miners were working, and the mine owners were contemplating building a mill. In April, the fortunes of the mine reached a turning point, as the Gold Bar Company gave Charles M. Schwab, the famous steel millionaire and mining promoter, an option to purchase the property. Descriptions of the deal varied, but Schwab had the option to purchase the mine for $1,000,000 by May and sent his engineers out to examine the mine before exercising his option, and the Bullfrog District waited in anticipation. The control of a mine by a man with the assets of Schwab could only mean good things for the entire district.

While Schwab pondered the deal, the Gold Bar continued to report discoveries of valuable ore. April saw such promising development that the mine owners privately expressed the hope that Schwab would let his option expire without buying the mine. After digesting the latest company reports, the Rhyolite Herald called the Gold Bar “one of the biggest things in the far-famed State of Nevada.”

But that year’s San Francisco fire and earthquake dampened the mood of unbounded optimism. Schwab requested several extensions of his option, and eventually, the deal fell through. The owners put on a good face, declaring they were glad Schwab had not bought. Mine developments continued despite the San Francisco disaster’s effects on financial circles.

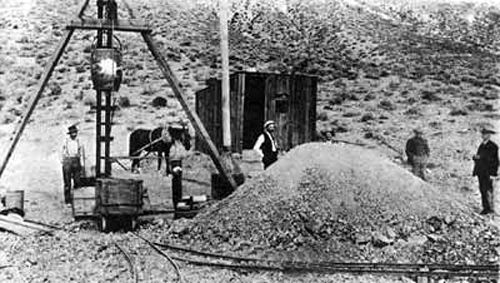

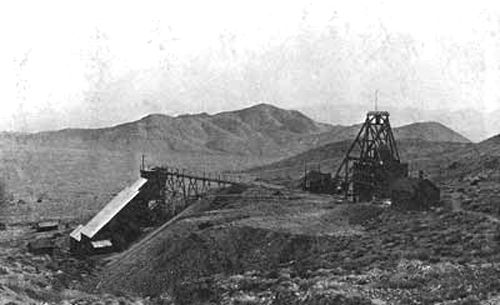

The Gold Bar Company continued operations through the intense heat of the summer. The mine now employed twenty-five men, and its main shaft reached a depth of 330 feet by the end of July. However, it became apparent that the Gold Bar was a low-grade mine that would have to operate its own mill to make a profit. Development continued, and by the end of 1906, The Gold Bar property included a hoisting plant and gallows frame, a small engine house, a blacksmith shop, a boarding house, an office building, and miscellaneous equipment.

In early January 1907, the Gold Bar announced it would build a mill on its property, but no further details were released. To help finance the construction, the mine began to ship ore to the newly completed Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad terminus at Rhyolite.

Gold Bar Mine, Nevada

In June, the company announced it had a contract to construct a 10-stamp mill. Work soon began on the mill foundations, and the company started laying a pipeline from its spring to the mill site.

Work on the mill slowly progressed during the last months of 1907, but stock prices were falling despite the evidence that the Gold Bar was evolving from a developing to a producing mine. The mill building was completed in December 1907, but delays in obtaining electrical power and equipment began to plague the company. However, the delays were overcome, and the Gold Bar Mill began operations in January.

Unfortunately, the mill had problems with leaking pipelines. Still, production continued until April, as rumors circulated that the mine would be forced to replace the entire pipeline to solve the water problem. On April 25, the mine and mill were closed to refurbish the mine and pipeline. The company soon announced plans to replace the entire pipeline and install expensive cyanide treatment machinery. Ominously, the company did not announce a definite date for the beginning of the improvement work, and its stock declined rapidly.

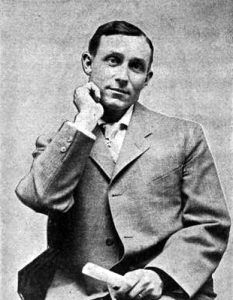

With the benefit of hindsight, it suddenly became apparent that something had been wrong with the Bullfrog Gold Bar Mining Company for some time. Its superintendent, L.E. Bedford, had quietly resigned on March 21, which looked strange at a time when the Gold Bar was finally beginning to produce.

In May, suspicions were confirmed when a prominent New York brokerage firm announced that the recent decline of Gold Bar stock was due to a Western bank instructing the company to sell a large block of Gold Bar regardless of the market price conditions. Someone knew that the Gold Bar was about to fail. Three weeks later, the Rhyolite Herald reported that over 200,000 shares of the company’s stock had been sold, and the dumping continued. In the meantime, the two principal controllers of the Gold Bar — J.P. Loftus and James R. Davis, left for a two-month vacation in Europe, announcing that they would look at the problems upon their return.

While the pair were abroad, however, their attorneys were not idle. The Nevada Exploitation Company, an aptly named Goldfield Concern, filed suit for an attachment on the assets and property of the Gold Bar Company to recover $36,300, which it had advanced to the Gold Bar to finance the construction of its mill. The Nevada Exploitation Company’s owners were the same principal owners of the Gold Bar—Loftus and Davis.

In essence, Loftus and Davis were thus suing themselves. Still, if they won, the Gold Bar would become the property of the Nevada Exploitation Company, and the remaining owners of Gold Bar stock would be left holding the bag.

The Rhyolite newspapers smelled fraud of the worst sort and started screaming. The Rhyolite Herald managed to obtain copies of company reports, which indicated that the mine superintendent, L.E. Bedford, had reported that the values of ore in the mine were not what he had claimed during past years. Principal owners Loftus and Davis said they were forced to sell their stock to repay the company’s debts and to close the mine and the mill because they were losing money. They claimed that the failure of the Gold Bar Mine was the fault of Superintendent Bedford, who had deceived both themselves and the public for over two years concerning the actual value of the ore deposits in the mine.

The Rhyolite Herald did not believe a word of it. Bedford had indeed been guilty of deceiving the public but not of deceiving Loftus and Davis, who were the company’s leaders. Only when Bedford discovered that Loftus and Davis planned to let him carry all the blame for the company’s fraudulent practices did Bedford decide that discretion was the better part of valor and leave town.

The Rhyolite Herald could cite too many direct quotes from Loftus and Davis concerning the prospects and values of the Gold Bar to believe they were innocent. One had only to review the directors’ production statements of the last several months to prove that point. It was evident to the newspaper that Loftus and Davis had intended to defraud the public from the beginning by loaning themselves money to build a mill, releasing false claims of mill returns, dumping the company’s stock on the market, then recovering their loans by foreclosing on the Gold Bar. Thus, they would be left with all the mill returns and stock sales profits and would lose no money at all. The public stockholders, however, would lose every penny they had invested in the Gold Bar Mine since 1905.

Despite the extreme anger of the local newspapers and stockholders around the nation, Loftus and Davis’s plans were completed with hardly a hitch. The Nevada Exploitation Company won its suit against the Gold Bar Company, and in December 1908, the Gold Bar Mine and Mill were sold to the Nevada Exploitation Company. Holders of Gold Bar stock, which had plunged to 3¢ per share, were left with nothing but waste paper in their hands.

Not content with their coup, Loftus and Davis then announced a grand reorganization of the Gold Bar Mine, proposing reincorporating as the New Gold Bar Mining Company.

Gold Bar Mine stock.

With a capitalization of 1,000,000 shares and a par value of $1 each, they offered to sell 600,000 shares in the new company to stockholders of the old at a special discount rate of 7¢ per share. They announced that the money thus raised would pay off the debt owed by the Gold Bar to Nevada Exploitation, after which the mine would be free to resume operations.

The Rhyolite Herald soon managed to secure an interview with Loftus and Davis, at which the Herald reporter questioned them about many conflicting reports they had earlier given about the original Gold Bar Mine. Time and again, Loftus and Davis insisted that there had been no intent to defraud the public. Finally, the reporter asked why the company had dumped its stock after determining that the mine and mill were a failure and would have to be closed down, concluding with, “What kind of treatment is that for the public to receive at your hands?”

Loftus’ reply amply summed up the philosophy of the Gold Bar Company. “I am not the guardian of the public. It is up to the public to decide these things for themselves.” When further pressed by the reporter as to the lack of ethics displayed by the company, Loftus reiterated his feelings in the best tradition of the nineteenth-century robber barons — “The public be damned.”

The local newspapers continued to be full of attacks upon Loftus and Davis’s motivations, characters, and ancestry. As the attacks continued, the Rhyolite Daily Bulletin reintroduced another factor everyone seemed to have forgotten. They reminded the public that the company had awarded the contract for constructing the Gold Bar mill to the Loftus–Davis Company of Goldfield. It was no wonder, said the Bulletin, that the Gold Bar Company had been willing to accept a poorly designed and built mill with rotten water pipes, a lack of cyanide treatment facilities, and other defects.

The fraud’s full extent has become apparent for the first time. Not only had a Loftus-Davis-controlled company loaned the Gold Bar the money to build its mill, but it had been built by yet another Loftus-Davis Company. How much of the almost $50,000 paid by the Gold Bar to that construction company represented a pure profit? And how did Loftus and Davis have the nerve to sue the Gold Bar to recover the costs of construction when they had already paid themselves for the actual construction work? The Bulletin’s question, of course, went unanswered.

Indeed, Loftus and Davis inexplicably seemed unaware of the extreme wave of hatred directed towards them, for they blithely persisted in advertising for investors in their reorganization efforts. Their advertisements fell upon barren ground. No one who had been burned by one of Nevada’s most complete swindles was willing to suffer again, and the reorganization plans soon fizzled out.

Ironically, at about this time, the United States Geologic Survey published its report on the Bullfrog District, stating: “Although a little rich ore has been found in the Gold Bar Mine, it is evident that the deposit is to be regarded as a large mass of low-grade material, such as can be worked, if at all, only on a considerable scale and by the most economical methods possible in this district.”

Although the Gold Bar affair was now finished, it was some time before all the dust settled. Angry stockholders continued to write letters to the Rhyolite newspapers, denouncing the fleecing they had taken. Loftus and Davis experimented with several more attempts at reorganization for several months. Neither had any success.

More annual reports of the Gold Bar Company were dug out and exposed in the newspapers, including one of June 1906, which stated that the company had over two million dollars of gold ore in sight.

Several individuals and companies made feeble efforts to tease and revive the mine, but all failed before they started. One thing became abundantly plain—the Gold Bar Mine had no paying ore. The Nevada Exploitation Company, however, paid its taxes upon the Gold Bar property in December 1909 to protect its investment in the mill and machinery located on the property, but no work was done that year.

In June 1910, when the Gold Bar Mine had been idle for over two years, the Nevada Exploitation Company announced that its mill buildings and machinery were for sale. Still, no one seemed interested in purchasing a poorly designed mill. Finally, in February of 1911, the company succeeded in selling the mill to the Round Mountain Mining Company for transfer to another Nevada mining district. Interestingly, J.P. Loftus was a partial Round Mountain Mining Company owner. By this time, Loftus and Davis felt safe to show their faces in the Bullfrog District when they came to close the deal. The two men still insisted that they had been innocent all along and that the sole cause behind the Gold Bar’s problems had been the deceptions practiced by former Superintendent Bedford upon the company and the public. No one believed them, but the Bullfrog District was probably glad to see the Gold Bar mill, a constant reminder of a past failure, shipped away in April 1911.

Between 1910 and 1919, the Nevada Exploitation Company continued to hold title to the ground and paid county taxes each year. The company paid $100 of labor each year on each claim to avoid higher taxes. But in 1920, Loftus and Davis finally gave up and quit paying taxes, and the Gold Bar joined its Bullfrog contemporaries on the delinquent tax list of the Nye County Treasurer.

The Gold Bar Mine rested on the county delinquent tax list from 1922 until 1942, except in 1937, when the mine was briefly worked. Then, in 1942, a man named Mike Chulick from California paid the back taxes of the Gold Bar, took ownership, and incorporated himself into the Gold Bar Mining Corporation. Whether for reasons of nostalgia or otherwise, the Gold Bar Mining Corporation still retains title to the mine, dutifully paying county taxes of from $110 to $150 each year. No serious mining endeavors, however, were ever carried out.

The story of the Bullfrog Gold Bar Mining Company is not pleasing. However, it is all too typical of the mining history of the early twentieth century. What started as a legitimate effort to exploit a high-grade gold deposit turned into a high-grade fraud when its owners realized that the Gold Bar was a low-grade mine and was not the sort from which fortunes are made.

Gold Bar Mine and Mill, Nevada, 1908

Like many mining promoters before and since, Loftus and Davis determined to mine the pockets of stockholders when it became evident that mining the ground would not prove profitable. Given the boom spirit and unbounded optimism of the Bullfrog District, which is most typical of mining camps throughout history, it is not altogether surprising that Loftus and Davis were so successful.

As is evident by now, the Gold Bar Mine was never a large producer of gold. It is impossible to determine how much ore was ever taken out of the ground since most of the available figures are those released to the press by the company itself. Two things, though, are abundantly clear: the private stockholders of the Gold Bar Company never made any money, and Loftus and Davis never lost any. The money those two promoters gained from their various swindles will never be known.

Gold Bar Hoisting Plant, 1906.

Like the area around the Original Bullfrog Mine, the ground surrounding the Gold Bar Mine was covered with other claims shortly after the initial successes of the Gold Bar Mine were publicized. As usual, most of these companies incorporated the words “Gold Bar” into their titles, staked out ground as close as possible to it, and tried to attract investors. Some of these mining companies never actually mined. All of them failed.

Chief among these companies who tried to find ore were the Gold Bar Extension, which operated intermittently from June 1905 to February 1908; the Gold Bar Annex, which existed from February 1906 to August 1907; the Original Gold Bar Extension, which ran from April to November 1906; and the Gold Bar South Extension, with a life-span from April 1906 to April 1907. None of these companies ever found any ore, although a few of them could list and sell their stocks for a short time. Over the years, the property has changed hands several times.

Today, the remains of the Gold Bar Mine are challenging to discern from those of the Homestake-King Mine, which was situated next to it. The former site of the Homestake-Gold Bar camp is marked only by debris, but prospect holes, dumps, and shafts dot the landscape. The Gold Bar property still reveals a few shafts, adits, and the remains of a crude headframe, but the rest of the operations have disappeared. The Gold Bar mill was carted away in 1911, but its concrete and brick foundations still mark the site.

Source: Death Valley Historic Resource Study. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2024.

Also See: