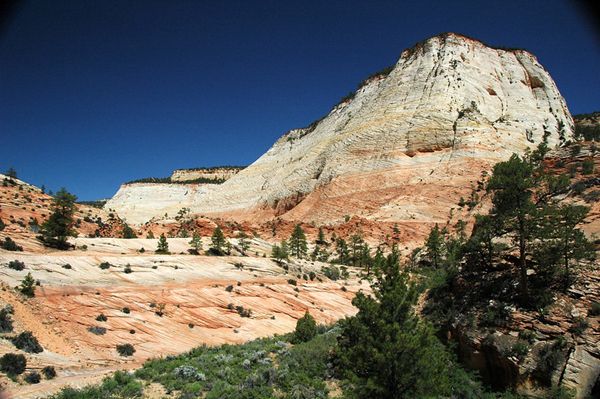

The White Cliffs of Utah, photo courtesy Bureau of Land Management.

The high, rugged, and remote region of southern Utah has several legends and tales hidden within its bold plateaus and multi-hued cliffs, one of which is the tale of the White Cliffs Gold Ledge.

The tale begins with an old prospector, George Brankerhoff, telling John Lorenzo Hubbell, of Hubbell Trading Post fame, about a cavern in the White Cliffs of Southern Utah that was laced with white quartz stalactites caked with gold. It is a mystery why this old prospector told the story to Hubbell rather than following up himself.

When Brankerhoff shared the story with Hubbell in 1870, John Lorenzo was still a young man working as a sutler’s clerk at Fort Wingate, New Mexico. Hubbell never heard from the old prospector again, but he never forgot the story.

Three years later, when Hubbell was 20 years old, the adventurous young man set out alone, traveling to Utah and following the old prospector’s directions in search of the gold ledge. Accurately remembering the tale, Hubbell first traveled to Kanab, Utah, then to Johnson Creek before turning eastward to the White Cliffs. He then followed the base of the White Cliffs to within three miles of Deer Springs Wash, where he would see a V-shaped cleft pointing downward. Brankerhoff had told him that the cleft would appear to be closed off from fallen sandstone; however, there would be a narrow space that could be squeezed through. Through the gap could be found a small stream of spring water that would disappear into the rocks beneath the V-shaped entrance. Once through the crevice, space would open wider and deeper into a cavernous space, from the ceiling of which would be hanging icicle-like quartz stringers laden with gold.

A seasoned desert traveler, Hubbell searched for weeks but could never find the V-shaped opening described by Brankerhoff. Finally, he decided to travel to Panguitch, Utah, some 65 miles north of Kanab, to see if he could find out more information from the locals. Though he took a job in a general store, he was not accepted by the locals due to his Mexican heritage. To make matters worse, he was making friendly with a local girl who also had the attention of a Christian bishop. The next thing you know, he found himself in a gunfight and later was attacked by a dozen local men. Though Hubbell was wounded in the attack, he killed two of his attackers defending himself. He then stole a horse and fled to Lee’s Ferry, Arizona. Obviously, he had received no help from the locals regarding the terrain of the White Cliffs.

After his recovery, he returned to his birthplace in Parajito, New Mexico. A few years later, he would begin building his Indian Trading Post empire. Still, he wouldn’t let go of the Lost Ledge Tale. Over the next several decades, he enticed several prospectors into looking for the ledge in exchange for grubstaking them. However, none were able to find it.

John Lorenzo Hubbell started his first trading post in 1878, eventually creating an empire of 30 such trading posts in Arizona, New Mexico, and California.

Then, a man named Warren Peters came along in 1891. Peters, a 61-year-old seasoned prospector, had just sold two silver claims in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado before entering New Mexico. Peters stopped in Gallup along the way with plans to prospect in the gold camps of the Mogollon Mountains in the southwest part of the state. There, he met John Lorenzo Hubbell. Once again, Hubbell saw an opportunity and shared the tale with Peters, who was so interested that he traveled with Hubbell to his home in Ganado, Arizona. While there, Hubbell provided Peters with all of the details as well as drawing a map of the White Cliffs, and Peters agreed to look. In May 1891, Peters set out to see if he could find the lost ledge. One can only imagine how he might have felt when he spied the location. Making his way through the narrow passage, he spied the icicle-like formations. Wasting no time, he knocked down several 20-inch-long stalactites, which scattered chunks of gold as they fell.

Filling several pouches with the gold, he loaded them onto two burrows and headed to the nearest railhead at Marysvale, some 80 miles to the north. He then traveled to Salt Lake City to sell his gold. However, he found that it would have to be shipped to Denver. After waiting more than a month, he finally received the payment. Thrilled at the amount, he made another trip back to the White Cliffs in August 1891.

He re-supplied and returned, confident that he could find the cleft again. However, when he found himself at Deer Springs Wash, he knew he had gone too far. Surprised that he had missed it, he backtracked and began to search again. Back and forth, he searched in vain for the V in the cliffs but was not able to find it a second time.

Frustrated, he continued to look until it was almost winter before finally making his way back to Hubbell in Arizona. The two theorized throughout the winter, wondering why it had been so easy for Peters to find the ledge the first time and impossible the second. They planned to return to Utah in the spring. However, when the time came, Hubbell did not go but rather sent a friend of his named Henry “Wild Hank” Sharp and two Navajo Indians named Little Chanter and Black Horse.

As the four prepared to leave on April 5, 1892, Hubbell warned them of dangerous men who inhabited that portion of southern Utah. However, the four prospectors were armed and set out on their way, along with 20-pack mules and plenty of supplies.

White Cliffs, Utah by James St. John/Flickr

When they arrived at the White Cliffs, they found cattle grazing on the range but paid no mind and set up camp at the base of the cliffs near a spring. The next day, they split up into two pairs and began searching for the opening. Peters and Sharp returned to camp first to find six men there. Eyeing them warily, they slowly approached the camp and could see that their belongings had been gone through.

When Peters inquired about what was going on, the “leader” of the bunch indicated that the area was rife with cattle thieves and that his cattle were grazing the range. Though Peters replied that they were prospectors, had no interest in the cattle, and the land was public domain, the cowboy adamantly insisted that they leave.

With a last threatening warning to vacate, the cowboys rode off. The four prospectors remained in camp for the evening and, the next day decided they would not split up and would carry their arms with them as they continued to search for the crevice. However, when they examined their pistols and rifles, they found every one of them had been tampered with. Deciding to pack everything up, they planned to move the camp some four miles east to Deer Springs, Wash. Moving slowly over the next four days, they searched for the lost ledge along the way before finally making a second camp near Deer Springs Wash.

Over the next several days, they continued their thorough search of the White Cliffs, while at night, they worried about the dangerous cowboys. When they returned to camp after a day of searching, the Navajo found unknown tracks around the camp. Someone had obviously been there. They decided they would spend just one more day searching and then leave. In the meantime, they split up the camp, moving their pack animals and most of their supplies to the east side of the wash while leaving their food and utensils at the original camp. After supper, the four moved to the east side of the wash to bed down for the night. However, as Peters and Sharp discussed the situation, they spied 15 riders coming in from the west. Halting at the abandoned camp, one of them yelled that they were county officers and the prospectors were under arrest.

The four prospectors took cover, and Peters responded, “What are the charges?”

The leader of the cowboys accused them of cattle rustling, but Peters responded that they were nothing more than a mob of cowboys and they would shoot if the cowboys advanced. After about a minute, bullets began to reign in Peter’s direction, and the prospectors fired back. Hidden by cover, they were able to force back the cowboys, but in the meantime, Peters had taken a bullet in the leg.

Sharp and the Indians immediately began to pack up, bandaged Peter’s wound and took off back toward Arizona. Fearful of being trailed, they moved as fast as they could throughout the night, not making camp until they were well into Arizona.

After allowing Peters some time to recover, they made their way back to Hubbell, who quickly decided that the gold was not worth pursuing if someone might die. Peters returned to his home in Kansas, and the other three to their respective homes and businesses. Hubbell never tried again to send prospectors into southern Utah.

Later, rumors circulated that a cowboy, maybe the same one who had threatened the prospectors, had blown shut the entrance to the crevice because he hadn’t wanted a bunch of prospectors on “his range.”

The legend says that the lost ledge of gold is still hidden somewhere in the White Cliffs. However, these lands are now part of the National Park System, which does not allow treasure hunting.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2024.

Also See:

John Lorenzo Hubble and the Hubble Trading Post

See Sources.