By Hubert Howe Bancroft in 1889

The threat uttered by Brigham Young during his interview with Captain Stewart Van Vliet on September 9, 1857, was speedily fulfilled — so speedily that, at first sight, its execution would appear to have been predetermined. “If he declared, the government dare to force the issue, I shall not hold the Indians by the wrist any longer.” “If the issue comes, you may tell the government to stop all emigration across the continent, for the Indians will kill all who attempt it.” Two days later, the Mountain Meadows Massacre occurred about 300 miles south of Salt Lake City.

The threat and the deed came so close together that many believed one resulted from the other. But a moment’s reflection will show that they were too nearly simultaneous for this to be the case; that in the absence of telegraph and railroad, it would be impossible to execute such a deed 300 miles away in two days.

Indeed, it may as well be understood at the outset that this horrible crime, so often and so persistently charged upon the Mormon church and its leaders, was the crime of an individual, the crime of a fanatic of the worst stamp, one who was a member of the Mormon church, but of whose intentions the church knew nothing, and whose bloody acts the members of the church, high and low, regard with as much abhorrence as any out of the church. Indeed, the blow fell upon the brotherhood with threefold force and damage.

The cruelty of it wrung their hearts; there was the odium attending its performance in their midst, and there was the strength it lent their enemies further to malign and molest them. The Mormons denounce the Mountain Meadows Massacre and every act connected therewith as earnestly and as honestly as any in the outside world. This is abundantly proven and may be accepted as a historical fact.

In the spring of 1857, 136 Arkansas emigrants, including a few Missourians, set forth for southern California. It included about 30 families, most of them related by marriage or kindred, and its members were of every age, from the grandsire to the babe in arms. They belonged to the class of settlers of whom California was in need. Most of them were farmers by occupation; they were orderly, sober, and thrifty, and among them was no lack of skill and capital. They traveled leisurely and in comfort, stopping at intervals to recruit their cattle, and about the end of July, arrived at Salt Lake City, where they hoped to replenish their stock of provisions.

For several years after the gold discovery, the arrival of an emigrant party was usually followed, as we have seen, by friendly traffic between saint and gentile, the former thus disposing, to good advantage, of his farm and garden produce. But now all has changed. The army of Utah was advancing on Zion, and the Arkansas families reached the valley at the very time when the Mormons first heard of its approach, perhaps while the latter were celebrating their tenth anniversary at Big Cottonwood Canyon. Moreover, wayfarers from Missouri and Arkansas were regarded with special disfavor; the former for reasons that have already appeared, the latter on account of the murder of a well-beloved apostle of the Mormon church.

Indeed, it may as well be understood at the outset that this horrible crime, so often and so persistently charged upon the Mormon church and its leaders, was the crime of an individual, the crime of a fanatic of the worst stamp, one who was a member of the Mormon church, but of whose intentions the church knew nothing, and whose bloody acts the members of the church, high and low, regard with as much abhorrence as any out of the church. Indeed, the blow fell upon the brotherhood with threefold force and damage.

He was acquitted, but it is alleged by anti-Mormon writers, and tacitly admitted by the saints, that he was sealed to Hector McLean’s wife, who had been baptized into the faith years before while living in San Francisco, California, and in 1855 was living in Salt Lake City. McLean swore vengeance against the apostle, who was advised to make his escape and set forth on horseback, unarmed, through a sparsely settled country, where, under the circumstances, escape was almost impossible.

His path was barred by two of McLean’s friends until McLean himself, with three others, overtook the fugitive when he fired six shots at him, the balls lodging in his saddle or passing through his clothes. McLean then stabbed him twice with a bowie knife under the left arm, whereupon Parley dropped from his horse, and the assassin, after thrusting his knife deeper into the wounds, seized a derringer belonging to one of his accomplices and shot him through the breast. The party then rode off, and McLean escaped unpunished.

Thus, when the Arkansas families arrived at Salt Lake City, they found the Mormons in no friendly mood and, at once, decided to break camp and move on. They had been advised by Elder Charles C. Rich to take the northern route along the Bear River but decided to travel by way of southern Utah. Passing through Provo, Springville, Payson, Fillmore, and intervening settlements, they attempted everywhere to purchase food, but without success. Toward the end of August, they arrived at Corn Creek, some 15 miles south of Fillmore, where they encamped for several days. In this neighborhood, on a farm set apart for their use by the Mormons, lived the Pah Vants, whom, as the saints allege, the emigrants attempted to poison by throwing arsenic into one of the springs and impregnating their own dead cattle with strychnine.

It has been claimed that this charge was disproved, and what motive the Arkansas party could have had for thus surrounding themselves with treacherous and blood-thirsty foes has never been explained. In the valleys throughout the southern portion of the territory grows a poisonous weed, and it is possible that the cattle died from eating this weed. It has been intimated that those who accused the emigrants of poisoning the Pah Vants were not honest in their belief and that the story of the poisoning was invented, or at least grossly exaggerated, to make them solely responsible for the massacre. The fact has never been so established, notwithstanding the report of the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, who states that none of this tribe were present at the massacre.

Cattle at waterhole

The emigrants continued their journey to Beaver City and then to Parowan. Grain was scarce this year, and the emigrants could not purchase all they desired for their stock, though they obtained what they required at this place for their own immediate necessities. Arriving at Cedar City, they purchased about 50 bushels of wheat, which was ground at a mill belonging to John D. Lee, formerly commander of the fort at Cedar City, but then an Indian agent in charge of an Indian farm near Harmony.

It is alleged by the Mormons, and on good authority, that during their journey from Salt Lake City to Cedar, the emigrants were guilty of further gross outrage. If we can believe a statement made in the confession of Lee, a few days before his death, Isaac C. Haight, president of the stake at Cedar City, accused them of abusing women, of poisoning wells and streams at many points on their route, of destroying fences and growing crops, of violating the city ordinances at Cedar City, and resisting the officers who attempted to arrest them. These and other charges, even more improbable, have been urged in extenuation of the massacre. Still, little reliance can be placed on Lee’s confession; most appear unfounded. It must be admitted, however, that rather than see their women and children starve, they perhaps took by force such necessary provisions as they were not allowed to purchase.

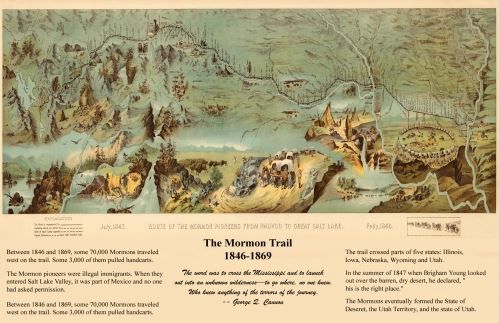

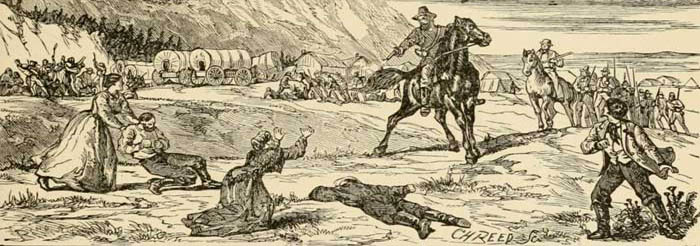

In this beautiful valley occurred one of the most horrific and controversial

massacres in U.S. history, drawing by H. Steinegger, Pacific Art Co, 1877.

Near Cedar City, the Spanish Trail to Santa Fe branched off from what was then known as Fremont’s route. About 30 miles to the southwest of Cedar and within 15 miles of the route line are the Mountain Meadows, which form the divide between the waters of the Great Basin and those that flow into the Colorado River. At the southern end of the meadows, four to five miles long and one in width but running to a narrow point, is a large stream, the banks of which are about ten feet tall. Close to this stream, the emigrants were encamped on September 5, almost midway between two ranges of hills, some 50 feet high and 400 yards apart. On either side of their camp were ravines connected with the stream bed.

It was Saturday evening when the Arkansas families encamped at Mountain Meadows. On the Sabbath, they rested, and at the usual hour, one of them conducted divine service in a large tent, as had been their custom throughout the journey. At daybreak on September 7, while the men were lighting their campfires, Indians fired upon them, or white men disguised as Indians, and more than 20 were killed or wounded, their cattle having been driven off meanwhile by the assailants, who had crept on them under cover of darkness.

The survivors now ran for their wagons and, pushing them together to form a corral, dug out the earth deep enough to sink them almost to the top of the wheels; then, in the center of the enclosure, they made a rifle pit large enough to contain the entire company, strengthening their defenses by night as best they could. Thereupon, the attacking party, which numbered from three to four hundred, withdrew to the hills on the crests of which they built parapets, whence they shot down all who showed themselves outside the entrenchment.

The emigrants were now under siege, and though they fought bravely, they had little hope of escape.

All the outlets of the valley were guarded; their ammunition was almost exhausted; of their number, which included a large proportion of women and children, many were wounded, and their sufferings from thirst had become intolerable. Down in the ravine, and within a few yards of the corral, was the stream of water; but only after sundown could a scanty supply be obtained, and then at great risk, for this point was covered by the muskets of the Indians, who lurked all night among the ravines waiting for their victims.

Four days the siege lasted; on the morning of September 5, a wagon was seen approaching from the northern end of the meadow and, with it, a company of the Nauvoo legion. Within a few hundred yards of the entrenchment, the company halted, and one of them, William Bateman by name, was sent forward with a flag of truce. In answer to this signal, a little girl dressed in white appeared in an open space between the wagons. Halfway between the Mormons and the corral, Bateman was met by one of the emigrants, Hamilton, who promised protection for his party on the condition that their arms were surrendered, assuring him that they would be conducted safely to Cedar City. After a brief parley, each one returned to his comrades.

By whose order the massacre was committed, or for what reasons other than those already mentioned, has never yet been ascertained, but as to the incidents and the plan of the conspirators, we have reliable evidence. During the week of the massacre, Lee, with several other Mormons, was encamped at a spring within half a mile of the emigrants’ camp and, as was alleged, though not distinctly proven at his trial, induced the Indians by the promise of booty to make the attack; but, finding the resistance stronger than he anticipated, had sent for aid to the settlements of southern Utah. Thus far, the evidence is somewhat contradictory. There is sufficient proof, however, that, following a program previously arranged at Cedar, a company of militia, among whom were Isaac C. Haight and Major John M. Higbee, and which was afterward joined by Colonel William H. Dame, bishop of Parowan, arrived at Lee’s camp on the evening before the massacre.

It was then arranged that John D. Lee should conclude terms with the emigrants and, as soon as they had delivered themselves into the power of the Mormons, should start for Hamblin’s rancho, on the eastern side of the meadows, with the wagons and arms, the young children, and the sick and wounded. The men and women, the latter in front, were to follow the wagons, all in single file, and on each side of them, the militia was to be drawn up, two deep, and with twenty paces between their lines. Within two hundred yards of the camp, the men were to be brought to a halt until the women approached a copse of scrub oak, about a mile distant and near which Indians lay in ambush. The men were now to resume their march, the militia forming in single file, each walking by the side of an emigrant and carrying his musket on the left arm.

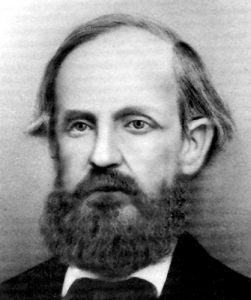

John Doyle Lee.

As soon as the women were close to the ambuscade, Higbee, who was in charge of the detachment, was to give the signal by saying to his command, “Do your duty,” whereupon the militia was to shoot down the men, the Indians were to slaughter the women and children, sparing only those of tender age, and Lee with some of the wagoners was to butcher the sick and wounded.

Mounted troopers were to be ready to pursue and slay those who attempted to escape so that, except infants, no living soul should be left to tell the tale of the massacre.

Entering the corral, Lee found the emigrants engaged in burying two of their party who had died of wounds. Men, women, and children thronged around him, some displaying gratitude for their rescue, some distrust and terror. The brother played his part well. Bidding the men to pile their arms in the wagons to avoid provoking the Indians, he placed the women, the small children, and a little clothing in them. While thus engaged, one Daniel McFarland followed Major Higbee’s orders to hasten their departure as the Indians threatened to renew the attack. The emigrants were then hurried away from the corral, the men, as they passed between the files of militia, cheering their supposed deliverers. Half an hour later, as the women drew near the ambuscade, the signal was given, and the butchery commenced. Most of the men were shot down at the first fire. Three only escaped from the valley; of these, two were quickly run down and slaughtered, and the third was slain at Muddy Creek, some fifty miles distant.

The women and those of the children who were on foot ran forward some two or 300 yards when they were overtaken by the Indians, among whom were Mormons in disguise. The women fell on their knees and, with clasped hands, sued in vain for mercy; clutching the garments of their murderers, as they grasped them by the hair, children pleaded for life, meeting with the steady gaze of innocent childhood the demoniac grin of the savages, who brandished over them uplifted knives and tomahawks. Their skulls were battered in, or their throats cut from ear to ear, and, while still alive, the scalp was torn from their heads. Some of the little ones met with a more merciful death, one, an infant in arms, being shot through the head by the same bullet that pierced its father’s heart. Of the women, none were spared, and of the children, only those not more than seven years of age.

Mountain Meadows Massacre, Utah.

Two of Lee’s wagoners, McMurdy and Knight, were assigned the duty, as it was termed, of slaughtering the sick and wounded. Carrying out their instructions, they stopped the teams as soon as the firing was heard and, with loaded rifles, approached the wagons where lay their victims, McMurdy being in front. “O Lord, my God,” he exclaimed, “receive their spirits; it is for thy kingdom that I do this.” Then, raising his rifle to his shoulder, he shot through the brain of a wounded man who was lying with his head on a sick comrade’s breast.

The Mormons were aided in their work by Indians, who, grasping the helpless men by the hair, raised their heads and cut their throats. The last victim was a little girl who came running up to the wagons, covered with blood, a few minutes after the disabled men had been murdered. She was shot dead within sixty yards of the spot where Lee was standing. The massacre was now completed, and after stripping the bodies of all articles of value, Brother Lee and his associates went to breakfast, returning after a hearty meal to bury the dead.

It was a ghastly sight that met them at this Wyoming of the west, amid the peaceful vales of Zion, and one that caused even the assassins to sicken and turn pale. The corpses had been entirely stripped by the Indians, who had also carried off the clothing, provisions, wagon covers, and even the bedding of the emigrants. In one group were the naked bodies of six or seven women; in another, those of ten young children, some of them mangled and most of them scalped. The dead were now dragged to a ravine nearby and piled in heaps; a little earth was scattered over them, but so little that it was washed away by the first rains, leaving the remains to be devoured by wolves and coyotes, the imprint of whose teeth was afterward found on their bones.

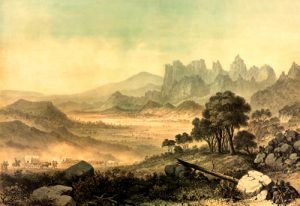

Historic view of Camp Floyd, Utah

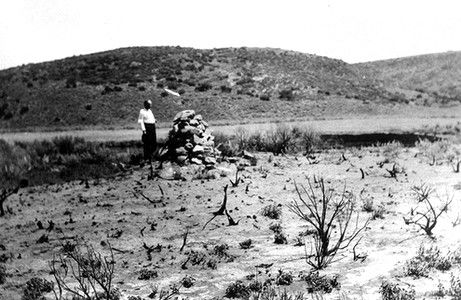

It was not until nearly two years later that they were decently interred by a detachment of troops sent for that purpose from Camp Floyd. On reaching Mountain Meadows, the men found skulls and bones scattered for the space of a mile around the ravine, whence wild beasts had dragged them. Nearly all the bodies had been gnawed by wolves so that few could be recognized, and their dismembered skeletons were bleached by prolonged exposure. Many of the skulls were crushed in with the but-ends of muskets or cleft with tomahawks; others were shattered by firearms, discharged close to the head. A few remnants of apparel were torn from the backs of women and children as they ran from the clutch of their pursuers, still fluttered among the bushes, and nearby were masses of human hair, matted and trodden in the mold.

Over the last resting-place of the victims was built a cone-shaped cairn, some 12 feet in height, and leaning against its northern base was placed a rough slab of granite, with the following inscription: “Here 120 men, women, and children were massacred in cold blood, early in September 1857. They were from Arkansas.” The cairn was surmounted by a cross of Cedar, on which were inscribed the words: “Vengeance is mine: I will repay, saith the Lord.”

Old Mountain Meadows Marker

The survivors of the slaughter were seventeen children, from two months to seven years of age, who were carried, on the evening of the massacre, by John D. Lee, Daniel Tullis, and others to the house of Jacob Hamblin and afterward placed in charge of Mormon families at Cedar, Harmony, and elsewhere.

All of them were recovered in the summer of 1858, except one who was rescued a few months later, and though thinly clad, they bore no marks of ill-usage. The following year, they were conveyed to Arkansas, the $10,000 appropriated by Congress for their recovery and restoration.

To Brigham Young, as governor and superintendent of Indian affairs, belonged the duty of ordering an investigation into the circumstances of the massacre and of bringing the guilty parties to justice. His reasons for evading this duty are best explained in his own words. In his deposition at the trial of John D. Lee, when asked why he had not instituted proceedings, he thus answered: “Because the president of the United States had appointed another governor and was then on the way here to take my place, and I did not know how soon he might arrive; and because the United States judges were not in the territory. Soon after Governor Cumming arrived, I asked him to take Judge Cradlebaugh, who belonged to the southern district, with him, and I would accompany them with sufficient aid to investigate the matter and bring the offenders to justice.”

The Mormons concerned in the massacre had pledged themselves by the most solemn oaths to stand by each other and always to insist that the deed was done entirely by Indians. For several months, it was believed by the federal authorities that this was the case; when it became known, however, that some of the children had been spared, suspicion at once pointed elsewhere, for among all the murders committed by the Utahs, there was no instance of their having shown any such compunction.

Moreover, it was soon ascertained that an armed party of Mormons had left Cedar City, had returned with spoil, and that the Indians complained of being unfairly treated in the division of the booty. Notwithstanding their utmost efforts, some time elapsed before the United States officials procured evidence sufficient to bring home the charge of murder to any of the parties implicated, and it was not until March 1859 that Judge Cradlebaugh held a session of court at Provo. At this date, only six or eight persons had been committed for trial and were now in the guard-house at Camp Floyd, some of them being accused of taking part in the massacre and some of other charges.

Accompanied by a military guard, as there was no jail within his district and no other means of securing the prisoners, the judge opened court on March 8. In his address to the grand jury, he specified a number of crimes that had been committed in southern Utah, including the massacre. “To allow these things to pass over,” he observed, “gives a color as if they were done by authority. The very fact of such a case as the Mountain Meadows shows that there was some person high in the estimation of the people and that authority did it… You can know no law but the laws of the United States and the laws you have here. No person can commit crimes and say higher authorities authorize them. If they have any such notions, they will have to dispel them.” The grand jury refused to find bills against any of the accused and, after remaining in session for a fortnight, were discharged by Cradlebaugh as “a useless appendage to a court of justice,” the judge remarking: “If this court cannot bring you to a proper sense of your duty, it can at least turn the savages held in custody loose upon you.”

Judge Cradlebaugh’s address was ill-advised. The higher authority of which he spoke could mean only the authority of the church, or in other words, of the first presidency, and to contemplate and threaten to impeach that authority before a Mormon grand jury was a gross judicial blunder. Though there may have been cause for suspicion, there was no fair color of testimony, and there is none yet, that Brigham or his colleagues were implicated in the massacre.

Apart from the hearsay evidence of Cradlebaugh and of an officer in the Army of Utah, together with the statements of John D. Lee, there is no basis on which to frame a charge of complicity against them. That the massacre occurred the day after martial law was proclaimed and within two days of the threat uttered by Brigham in the presence of Captain Stewart Van Vliet; that Brigham, as superintendent of Indian affairs, failed to embody in his report any mention of the massacre; that for a long time afterward no allusion to it was made in the tabernacle or the Deseret News — the church organ of the saints — and then only to deny that the Mormons had any share in it; and that no mention was made in the Deseret News of the arrival or departure of the emigrants; — all this was, at best, but presumptive evidence, and did not excuse the slur that was now cast on the church and the church dignitaries.

“I fear, and I regret to say it,” remarks the superintendent of Indian affairs in August 1859, “that with certain parties here, there is a greater anxiety to connect Brigham Young and other church dignitaries with every criminal offense than diligent endeavor to punish the actual perpetrators of crime.”

The judge’s remarks served no purpose except to draw forth from the mayor of Provo a protest against the presence of the troops as an infringement of the rights of American citizens. The judge replied that good American citizens need have no fear of American troops, whereupon the citizens of Provo petitioned Governor Alfred Cumming to order their removal. Cumming, who was then at Provo, was officially informed by the mayor that the civil authorities were prepared and ready to keep in safe custody all prisoners arrested for trial and others whose presence might be necessary. He, therefore, requested General Johnston to withdraw the force, which was then encamped at the courthouse, stating that its presence was unnecessary.

The general refused to comply, being sustained in his action by the judges, and on March 27 Cumming issued a proclamation protesting against all movements of troops except such as accorded with his instructions as chief executive magistrate. A few days later, the detachment was withdrawn.

Notwithstanding the contumacy of the grand jury, Cradlebaugh continued the sessions of his court, still resolved to bring to justice the parties concerned in the Mountain Meadows Massacre and crimes committed elsewhere in the territory. Bench warrants, based on sworn information, were issued against several people, and the United States marshal, aided by a military escort, succeeded in making a few arrests.

Among other atrocities laid to the charge of the Mormons was one known as the Aiken massacre, which also occurred during the year 1857. Two brothers of that name, with four others, returning from California to the eastern states, were arrested in southern Utah as spies, and, as was alleged, four of the party were escorted to Nephi, where it was arranged that Porter Rockwell and Sylvanus Collett should assassinate them. While encamped on the Sevier River, they were attacked by night, two of them being killed and two wounded, the latter escaping to Nephi, whence they started for Salt Lake City but were murdered on their way to Willow Springs. Although the guilty parties were well known, it was not until many years later that one of them, named Collett, was arrested and, in October 1878, was tried and acquitted at Provo. All the efforts of Judge Cradlebaugh availed nothing, and soon afterward, he discharged the prisoners and adjourned his court sine die, entering on his docket the following minute: “The whole community presents a united and organized opposition to the proper administration of justice.”

This antagonism between the federal and territorial authorities continued until 1874. At that date, an act was passed by Congress “concerning courts, and judicial officers in the territory of Utah,” commonly known as the Poland bill, whereby the summoning of grand and petit juries was regulated, and provisions were made for the better administration of justice. The first grand jury impaneled under this law was instructed by Jacob S. Boreman, then in charge of the second judicial district, to investigate the Mountain Meadows Massacre and find bills of indictment against the parties implicated. A joint indictment for conspiracy and murder was found against John D. Lee, William H. Dame, Isaac C. Haight, John M. Higbee, Philip Klingensmith, and others. Warrants were issued for their arrest, and after a vigorous search, Lee and Dame were captured, the former being found concealed in a hog pen at a small settlement named Panguitch on the Sevier River.

After some delay caused by the difficulty in procuring evidence, July 12, 1875, was appointed for the trial at Beaver City in southern Utah. At 11:00 a.m., the court was opened, Judge Boreman presiding, but the absence of witnesses caused further delay, and Lee had promised to make a full confession and thus turn state’s evidence. In his statement, the prisoner detailed minutely the plan and circumstances of the tragedy, from the day when the emigrants left Cedar City until the butchery at Mountain Meadows. He avowed that Higbee and Haight played a prominent part in the massacre, which, he declared, was committed in obedience to military orders, but said nothing as to the complicity of the higher dignitaries of the church, by whom it was believed that these orders were issued. The last was the very point that the prosecution desired to establish, its object, compared with which the conviction of the accused was but a minor consideration, being to get at the inner facts of the case. The district attorney refused, therefore, to accept the confession on the ground that it was not made in good faith. Finally, the case was brought to trial on July 23, and the result was that the jury, of whom eight were Mormons, failed to agree after remaining out of court for three days. Lee was then remanded for a second trial, held before the district court at Beaver City between September 13 and 20, 1876, with Judge Boreman again presiding.

The courtroom was crowded with spectators who cared little for the accused but listened with rapt attention to the evidence, which, as they supposed, would certainly implicate the church dignitaries. They listened in vain. In opening the case to the jury, the district attorney stated that he came there to try John D. Lee, not Brigham Young and the Mormon church.

He proposed to prove that Lee had acted in direct opposition to the feelings and wishes of the officers of the Mormon church, that utilizing a flag of truce, Lee had induced the emigrants to give up their arms, that with his own hands, the prisoner had shot two women, and brained a third with the but-end of his rifle; that he had cut the throat of a wounded man, whom he dragged forth from one of the wagons; and that he had gathered up the property of the emigrants and used it or sold it for his own benefit.

These charges and others relating to previously mentioned incidents were substantiated. The first evidence introduced was documentary and included the depositions of Brigham Young and George A. Smith and a letter written by Lee to the former, wherein he attempted to throw the entire responsibility of the deed upon the Indians. Brigham alleged that he heard nothing about the massacre until some time after it occurred and then only by rumor; that two or three months later, Lee called at his office and gave an account of the slaughter, which he charged to Indians; that he gave no directions as to the property of the emigrants, and knew nothing about its disposal; that on about September 10, 1857, he received a communication from Isaac C. Haight of Cedar City, concerning the Arkansas party, and in his answer had given orders to pacify the Indians as far as possible and to allow this and all other companies of emigrants to pass through the territory unmolested. George A. Smith, who had been suspected of complicity through attending a council at which Dame, Haight, and others had arranged their plans, denied that he was ever an accessory thereto. He also deposed that he had met the emigrants at Corn Creek, some eighty miles north of Cedar, on August 25 while on his way to Salt Lake City and that when he first heard of the massacre, he was in the neighborhood of Fort Bridger.

The first witness examined was Daniel H. Wells, who merely stated that Lee was a man of influence among the Indians and understood their language sufficiently to converse with them. James Haslem testified that between five and six o’clock on Monday, September 7, 1857, he was ordered by Isaac C. Haight to start for Salt Lake City and, with all speed, deliver a letter or message to Brigham Young. He arrived at 11:00 a.m. on the following Thursday and, four hours later, was returning with the answer. As he set forth, Brigham said, “Go with all speed, spare no horse-flesh. The emigrants must not be meddled with if it takes all of Iron County to prevent it. They must go free and unmolested.”

Samuel McMurdy testified that he saw Lee shoot one of the women and two or three of the sick and wounded who were in the wagons. Jacob Hamblin alleged that soon after the massacre, he met Lee within a few miles of Fillmore when the latter stated that two young girls, who had been hiding in the underbrush at Mountain Meadows, were brought into his presence by a Utah chief. The Indian asked what should be done with them. “They must be shot,” answered Lee; “they are too old to be spared.”

“They are too pretty to be killed,” answered the chief. “Such are my orders,” rejoined Lee, whereupon the Indian shot one of them, and Lee dragged the other to the ground and cut her throat.

I will make but one comment on the testimony that we have now before us. If Haslem’s statement was true, Brigham was an accomplice; if it was false, and his errand to Salt Lake City was a mere trick of the first presidency, it is highly improbable that Brigham would have betrayed his intention to Van Vliet by using the remarks that he made only two days before the event. Moreover, apart from other considerations, it is impossible to reconcile the latter theory with the shrewd and far-sighted policy of this able leader, who well knew that his militia was no match for the army of Utah and who would have been the last one to rouse the vengeance of a great nation against his handful of followers.

Lee was convicted of murder in the first degree and, being allowed to select the mode of his execution, was sentenced to be shot. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court of Utah, but the judgment was sustained, and it was ordered that the sentence be carried into effect on March 23, 1877. William H. Dame, Isaac C. Haight, and others who had also been arraigned for trial were soon afterward discharged from custody.

A few days before his execution, Lee confessed, in which he attempts to palliate his guilt, to throw the burden of the crime on his accomplices, especially on Dame, Haight, and Higbee, and to show that order of Brigham and the high council committed the massacre. He also made mention of other murders or attempts to murder, which, as he alleged, were committed by order of some higher authority.

“I feel composed and as calm as a summer morning. I hope to meet my fate with manly courage. I declare my innocence. I have done nothing designedly wrong in that unfortunate affair with which I have been implicated. I used my utmost endeavors to save them from their sad fate. Were they at my command, I would have given worlds to have averted that evil. Death to me has no terror. It is, but a struggle and all is over. I know I have a reward in heaven, and my conscience does not accuse me.”

— John D. Lee, March 13, 1877

John D. Lee Execution site.

Ten days later, he was led to execution at the Mountain Meadows. Over that spot, the curse of the almighty seemed to have fallen. The luxuriant herbage that had clothed it 20 years before had disappeared; the springs were dry and wasted, and now there was neither grass nor any green thing, save here and there a copse of the sagebrush or scrub oak, that served but to make its desolation still more desolate. Around the cairn that marks their grave still flit, as some have related, the phantoms of the murdered emigrants and nightly re-enact in ghastly pantomime the scene of this hideous tragedy.

At about 10:00 a.m. on March 23, 1877, a party of armed men alighting from their wagons approached the site of the massacre. Among them were the United States marshal, William Nelson, the district attorney, a military guard, and a score of private citizens. In their midst was John Doyle Lee. Blankets were placed over the wheels of one of the wagons to serve as a screen for the firing party. Some rough pine boards were then nailed together in the shape of a coffin, which was placed near the edge of the cairn, and upon it, Lee took his seat until the preparations were completed. The marshal now read the court’s order and, turning to the prisoner, said:

“Mr. Lee, if you have anything to say before the order of the court is carried into effect, you can do so now.”

Rising from the coffin, Lee looked calmly around for a moment and then, with an unfaltering voice, repeated in substance the statements already quoted from his confession and added:

“I have but little to say this morning. It seems I must be made a victim; a victim must be had, and I am the victim. I studied to make Brigham Young’s will my pleasure for 30 years. See now what I have come to this day! I have been sacrificed in a cowardly, dastardly manner. I cannot help it; it is my last word; it is so. I do not fear death; I shall never go to a worse place than I am now in. I ask the Lord, my God, to receive my spirit if my labors are done.”

A Methodist clergyman, who acted as his spiritual adviser, knelt by his side and offered a brief prayer, to which he listened attentively.

After shaking hands with those around him, he removed some of his clothing, handing his hat to the marshal, who bound a handkerchief over his eyes, his hands being free at his request. Seating himself with his face to the firing party and with hands clasped over his head, he exclaimed:

“Let them shoot the balls through my heart. Don’t let them mangle my body.”

The word of command was given; the report of rifles rang forth in the still morning air, and without a groan or quiver, the body of the criminal fell back lifeless on his coffin. God was more merciful to him than he had been to his victims.

John D. Lee Execution.

Written by Hubert Howe Bancroft, 1889. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2025. Bancroft’s text is not verbatim, as it has been heavily edited for the modern reader.

About the Author: This account of the Mountain Meadows Massacre was Chapter 20 of Hubert Howe Bancroft’s book, History of Utah, 1540-1886, published in 1889 by the San Francisco History Co. Though the context remains the same, the text is not verbatim, as grammatical, spelling and other minor changes have been made. Bancroft was born in Ohio and later moved to Buffalo, New York, where he worked in a bookstore. Later, he relocated to San Francisco, California, where he managed a bookstore from 1852 to 1868 and began his own publishing house. Accumulating an extensive library of historical material, he eventually gave up the bookstore business to devote himself entirely to writing and publishing history. Though his many works were well received, he was often criticized for lacking preparation and reflecting personal opinions and enthusiasm. He died in 1918 and was buried in Colma, California.

Also See: