By William Eleroy Curtis, 1883

Early in the 1800s, fables of the riches and splendors of the Spanish Hidalgos of New Mexico began to reach the ears of the frontier traders, and they came to believe that across the southwestern boundary, which was then the lower line of Kansas and Colorado, lay an unsurpassed market. The Spanish rulers were supposed to be rolling in luxury and given boundless extravagance. The return of Lieutenant Zebulon Pike from his long pilgrimage and perilous adventures gave the theories the substance of fact. In 1804, a French Creole named La Lande started from Kaskaskia, Illinois, for Santa Fe, New Mexico, with several pack mules laden with goods belonging to a trader named Morrison. He never returned and was thought to have been killed by the Indians.

In 1812, four men, inspired by Lieutenant Zebulon Pike’s reports, thought they would try to make their way through. They started from Booneville, Missouri, with a pack train laden with merchandise. The names of three bold adventurers were McKnight, Beard, and Chambers. They followed Pike’s trail to the foot of the mountains, along the Arkansas River, and then took a southerly course, arriving at Santa Fe without any exciting experience. This was the first endeavor to establish trade with the Spanish settlements, and it proved disastrous, for upon their arrival at the capital of New Mexico, the excitement over Pike’s arrest was revived. They were thrown into prison as spies, their goods were confiscated, and they narrowly escaped execution.

They found at Santa Fe, upon their arrival, a man named La Lande, who was supposed to have been lost but who went through safely, set himself up as a merchant with the capital that belonged to Morrison, his employer, and was living in luxury with a Mexican wife. The only American there was James Pursley, the first emigrant from the United States to New Mexico. Pursley was a trapper and, while following his trade along the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, had fallen in with some Indians who told him of the Spanish settlements a few hundred miles below. He decided to make them a visit and went first to Taos, New Mexico, a pueblo or village 70 miles north of Santa Fe on the Rio Grande, and then to the capital, where he took up a permanent residence, married a Mexican woman and kept a miserable hotel until his death, 24 years later. He was the only American to welcome the gallant Pike when the latter arrived at Santa Fe as a prisoner and acted as interpreter during his interviews with the authorities.

McKnight and his companions were imprisoned for nine years until the 1821 revolution led by Agustin de Iturbide. They were released and returned to Missouri in a canoe down the Arkansas River. Undaunted by his harrowing experience, in the following year (1822), Mr. Beard of the McKnight party induced some capitalists of St. Louis to furnish the means for another experiment, and he started again with a small party and several thousand dollars worth of merchandise laden upon pack-horses. They reached a point near La Junta, Colorado, safely. Still, they were overtaken by a violent snowstorm and driven into the timber of an island in the Arkansas River for shelter. A rigorous winter followed, and they were compelled to build huts for protection and remain there for three long months. Some of the party perished from exposure, and the rest nearly died of starvation. They were compelled to kill their horses for food, and Spring found them with a valuable cargo of merchandise in their hands with no means of transportation. In this emergency, they made a cache, a term used by Canadian voyagers to describe a place of concealment, digging deep pits on the bank of the river, burying their goods, and starting on foot over the mountains. They safely reached Taos, obtained some mules, and returned for their buried property, which was taken to Santa Fe and sold at an enormous profit.

The mossy pits where Beard buried his goods lie near Las Animas, very close to the boundary line between Colorado and New Mexico. For years, ranchmen who rode over that country after the roaming cattle pointed them out.

When these traders reached Santa Fe, the arrogant and insolent Hidalgos (Spanish Nobility), who had ruled the country commercially, as well as politically and socially, for so long, endeavored to dispose of them as McKnight and his party had been treated. However, since the revolution, there had been a new and more liberal administration inclined to encourage competition and welcome commerce, so the Santa Fe trade began.

The profits of the expedition were enormous, and Beard’s party returned to Missouri with their pack mules laden with wool, gold, silver, and turquoise, for which they had exchanged their merchandise. Up to this date, the New Mexicans had obtained all of their supplies from Spain by vessel to Vera Cruz, where they were transported at significant cost across the country and sold at exorbitant prices. Calicos that could be purchased in Missouri for a sixpence a yard cost two or three dollars at Santa Fe, and cutlery was in demand at almost any price.

Captain William Becknell was the next trader to start out. He left Missouri in 1821 with four companions and a stock of goods to trade with the Indians for furs. He met Beard’s returning party and, learning of their success with the Mexicans, went to Santa Fe instead, bringing back large profits to Booneville. Then Colonel Cooper went out in May 1822 with a party of 15 men and several thousand dollars worth of merchandise, which he exchanged at Taos for silver ornaments, wool, and skins.

Captain Becknell made a second trip the same year but with different results. Having tremendous confidence in his ability to find a shorter route to Santa Fe, the captain left his old trail and started across the country to avoid the circuitous valley of the river. It was a fatal mistake, as the party found themselves in a sandy desert without any water supply and wandered about for several days, enduring sufferings that passed description. They killed their dogs and cut off the ears of their mules in the vain hope of assuaging their thirst with the hot blood. Several of the men died, while the others pushed on with parched throats and burning flesh, following the cruel mirage of the prairie that has lured so many to destruction. The strongest of the party was fainting with fatigue and would soon have perished but for a buffalo that came upon them. They shot him for his blood and found his stomach distended with water. This filthy liquid saved their lives, and they followed the track of the animal to a creek at which he had just been drinking.

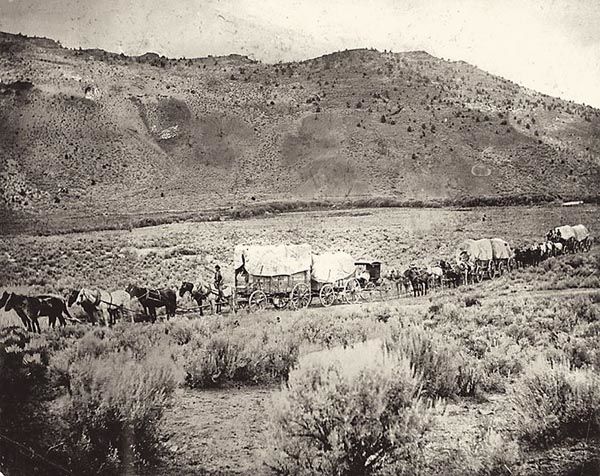

The profits of the trade with Santa Fe were so large that merchants of capital were enlisted, and parties started from Booneville, Missouri, nearly every month during the summer. In 1824, the trade became so large that wagons were introduced, and the first wheels passed over the prairie in May. The famous General Marmaduke, afterward Lieutenant Governor of Missouri and later a Confederate leader, was one of the party. The first caravan reached Santa Fe without difficulties, and the light wagons were a great curiosity to the New Mexicans, who had never seen anything better than the clumsy ox carts used by the native farmers.

So rapidly did train follow train that in 1825 the Honorable Thomas H. Benton secured from Congress an appropriation of $25,000 for “the survey and improvement of a wagon road from the Missouri River to the New Mexican boundary,” and under this authority, Major Henry Sibley, of the United States army, laid out what has since passed into the history of the frontier as the Santa Fe Trail, the longest, and in many respects, the most remarkable road in the world, 800 miles in length, without a bridge from end to end, and rising almost imperceptibly from an elevation of only 500 feet to a height of over 8,000 above the sea. The eastern terminus was originally at Booneville, then at Independence, then at St. Joseph, Missouri, receding as civilization advanced very slowly, but afterward with great rapidity when the railroad stretched itself out across the plains.

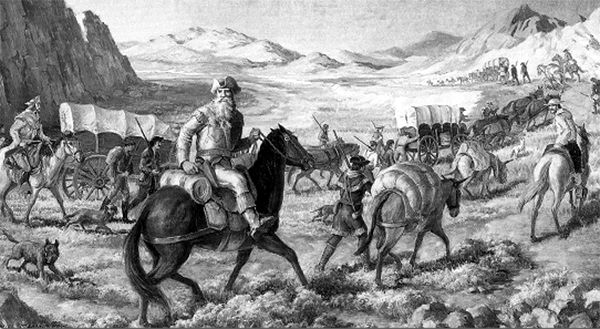

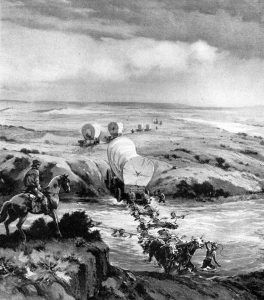

At one time, as many as 4,000 people were engaged in the Santa Fe trade, and capital of several millions of dollars was employed in its transactions. The traders would start from different points along the river, where the freight had been transferred from steamboats to the wagons, and a rendezvous at Council Grove, Kansas, a long piece of timber on the bank of the Kansas, or Kaw River. Here, several parties would come together and organize for the long march. A caravan captain was elected, every wagon had one vote, and there used to be lively contests for the choice. The idea of such an organization was to secure better protection from the Indians, and the trains that exercised the usual precautions were seldom attacked. They were generally composed of three or four hundred wagons, often carrying half a million dollars worth of property, with about three men to every two wagons. A small cannon was commonly carried, which was more effective in Indian warfare than a hundred muskets, and a regular system of guards and pickets was maintained. Very often, the wives and families of traders accompanied them on the prairie voyage, and it became a favorite journey for tourists and invalids.

Teamsters.

The captain of the caravan was chosen for his leadership ability and executive talent. The office was no sinecure, and few men could adequately fill it. The captain was an autocrat. His revolver was his scepter, and he would shoot a man down for a breach of discipline with as little remorse as he would kill a disabled mule. The Teamsters, “mule whackers,” “bull-whackers,” or “cow-punchers,” as they were variously called, were not a gentle or diffident class of men, and safety required the strictest discipline. Each man had his duties, and the captain decided any dispute, from whose decision there was no appeal. If a party member was dissatisfied with the captain’s government, he could leave the caravan and take the journey alone, but if he remained, he must obey.

Guides and scouts were always employed to look after camping places, where the three essentials, water, fuel, and grass, must be found, to hunt game for the expedition’s food, and to watch for Indian signs. This was the business of Kit Carson, the most remarkable and ablest plainsman this country has produced, whose name is associated with almost every step of progress in the Southwest.

The caravan used to follow its weary path in a long and lazy procession, four wagons abreast, and the traveler along the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad can see even today where the plow has not turned the sod. These deep ruts were made in the soft soil by the wagon wheels. At night, the wagons were formed in a hollow square, with their tongues out, making a safe and sheltered pen for the animals. Each party camped outside its wagons, and every man stood his turn on guard. With these precautions, the long journey across the plains was not attended with many hazards, and very seldom was one of the large trains attacked. The Indians confined their depredations to small and reckless parties, and disaster only followed carelessness. Kit Carson left on record his opinion that whiskey has killed more men on the frontier than the Indians, and there is no doubt of the fact. But ignorance of Indian customs and foolhardy recklessness have caused the sacrifice of many lives and property. Persons “wise in their own conceit” frequently thought they could shorten the route by leaving the trail and “cutting across lots” but invariably came to grief.

In 1833, a party of tourists and traders, of which a brother of General Robert C. Schenck was a member, left the trail to save time and distance, lost their reckoning, exhausted their provisions, and fired away all their ammunition at the game. They wandered about for several weeks in the most significant distress, killing their horses for food and feeding upon the leaves and roots of shrubs. The party was divided over a difference of opinion on the proper direction. One branch finally reached an Indian camp, where they were hospitably treated and permitted to return to the States. The others, among whom was Mr. Schenck, were never seen alive again, but months afterward, their bones were found and identified by some articles of clothing as they lay bleaching upon the prairie.

The lack of water in the summer season constituted the greatest danger. The western plains of Kansas were once the bottom of a great lake whose waves dashed against the Rocky Mountains. At the time when what geologists call “the great continental elevation” took place, the lake was raised above the sea level, and the vast area of water was gradually diminished by drainage until nothing. Still, ponds were left in the natural depressions and the streams” that carry the melting snows of the mountains to the sea. The winds lapped up the contents of the ponds and the sun, and the sands of their bottoms hardened into rock and made a mighty sarcophagus for the beasts, birds, fishes, and insects that were the original inhabitants. From a sea of water, the plains became a great earth ocean, and on every side, the waves of buffalo grass rolled up against the shores of the horizon. Where were once billows of water are now billows of sand, over which, in years past, the white fleets of prairie schooners used to encounter more cruel dangers than were ever confronted upon the sea. Indians and soldiers, battles and hunts, hunger and thirst, murder, fire, and rapine, have made long cemeteries of the two trails across the continent, one leading to the treasure storehouses of the Rocky Mountains and the other to the legendary land of Montezuma.

When the traders approached Santa Fe, rapid riders would be sent ahead to make contracts and engage warehouses, and the arrival of a caravan made a holiday in the quaint old Spanish town. Having sold their goods for Spanish dollars or exchanged them for silver or turquoise, the traders would spend several weeks in carousal, lose much of their money in the gambling houses, and then reload their wagons with wool and start on the homeward journey.

At that time, New Mexico belonged to Spain, and a heavy tariff was imposed upon all foreign traders, sometimes amounting to two and three hundred percent. The customs officers were very corrupt, and it is believed that little of the money they collected ever reached the government’s coffers. For a few years, Governor Armijo maintained a tariff of his own, exacting five hundred dollars for each wagon load, and those who paid this cheerfully are said to have easily escaped the other imposts.

In 1839, when the French blockaded all the Mexican seaports, the Santa Fe trade reached enormous proportions, as it was the only means Old Mexico and New Mexico had of securing supplies. It was suspended entirely in 1843 during the war between Texas and Mexico. Santa Anna issued a decree forbidding the importation of goods from the North and closing customs houses. However, the trail was opened again in 1848 when General Stephen Kearney captured Santa Fe and planted the Stars and Stripes upon the ancient mud “palace” of the haughty Dons. Business increased, a stage line was established, and finally, the railroads began to reach toward the Southwest with their iron arms. The forwarding houses kept advancing with the track, first to Emporia, then to Larnard and Fort Dodge, Kansas; La Junta, Colorado; and Las Vegas, New Mexico. The railroad track follows the old trail very closely, and the journey once five weeks long, soon became a scamper of only three days.

By William Eleroy Curtis, A Summer Scamper Along the Old Santa Fe Trail, and Through the Gorges of Colorado to Zion; Inter Ocean Publishing Company, 1883. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2025.

Also See:

Early Traders on the Santa Fe Trail